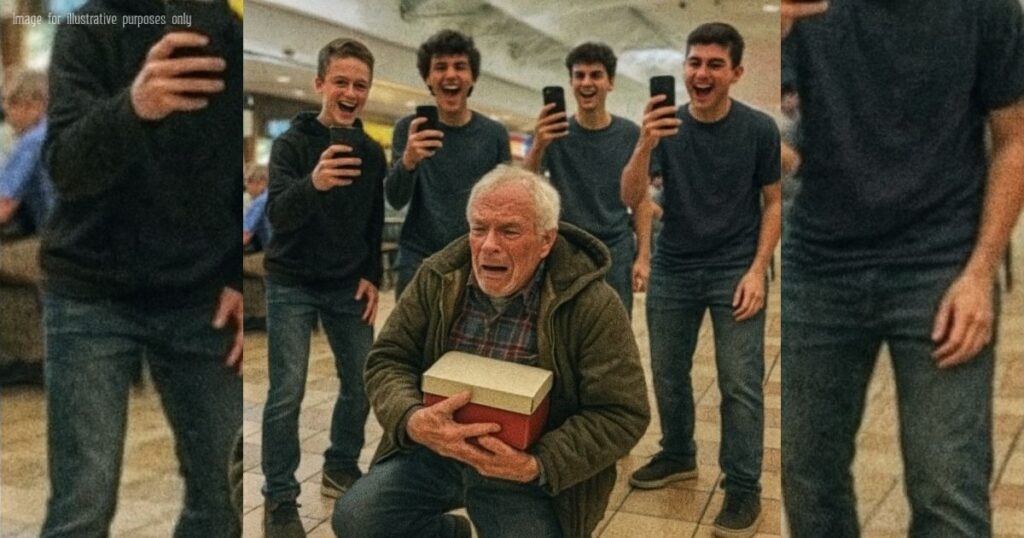

Three teenagers went live while a grandfather collapsed in the food court—thousands watched, and for a full minute, no one moved.

The first sound was a tray hitting tile, a clean clatter that made heads turn. The second was the thin wheeze a person makes when their body quits being a machine and becomes a plea.

I was ten feet away, wiping applesauce off my son’s sleeve with one hand and balancing a cardboard boat of fries in the other. It was Saturday at the Westfield in Greenwood—the kind of place where the air smells like cinnamon pretzels and cologne samples, where people wander under white skylights pretending weekends can last forever.

He went down between the smoothie kiosk and the carousel, right where the light pours in. White hair, plaid shirt, a winter coat zipped up too high like he didn’t trust the warm air. He clutched a shoebox to his chest, the cheap department-store kind with a purple size sticker on the side. He tried to stand, wobbled, then sank to his knees as if the floor had turned to sand beneath him.

“Start the live,” a teenage voice said behind me. “Dude, start it, start it, this is crazy.”

I turned. Three boys, phones up, arm length, eyes bright with that hunger you only get when a lens is open. You could see the reflection of the old man in their screens. You could see the little red LIVE badge.

“Someone call nine-one-one,” I said.

“Chill, lady,” the tallest one said, but he didn’t lower his phone. He shifted to get a better angle.

I pushed the stroller out of the path and knelt. My jeans soaked up something I didn’t want to think about on a public floor. The older man’s chest rose shallow and fell shallower. His fingers gripped the shoebox like it was a lifeline.

“Sir?” I said. “Sir, can you hear me?”

He blinked at me—blue eyes, the pale blue of winter sky behind power lines. Sweat had turned his hair to white wire against his forehead.

“My… grand—” He couldn’t quite find the last syllables.

“I’m here,” I said. “I’m calling for help.” I hit the emergency button on my phone and spoke the mall’s name, the level, the nearest store. My voice did that steady thing it does when the rest of me is shaking.

When the operator asked if anyone else could assist, I glanced up and met a dozen startled stares. People were frozen in the way crowds freeze—unsure if stepping forward makes you a target, unsure which direction mercy goes.

“Someone get the mall security,” I called. “And please bring a first-aid kit. Anyone?”

A barista’s head popped around the kiosk. “I’ll go,” she said, and sprinted.

The tallest boy edged closer, still broadcasting. “Yo, look at his hand on the box,” he said to his phone. “He won’t let it go.”

The older man tried to speak. I leaned closer.

“Shoes,” he whispered. “Dance… show tonight.”

“I’ve got you,” I said. “We’re going to get you there. Tell me your name.”

He closed his eyes, gathering a strand of air like thread. “Earl,” he breathed. “Earl Whitaker.”

“Earl, I’m Maya,” I said. “I’m with you, okay? Keep looking at me.”

The operator asked if I knew CPR. I did. Not from a class; from a day years ago when my father’s heartbeat turned into a stubborn door I couldn’t open. I learned after that, because grief had convinced me education could bargain with fate.

“Breaths are sounding shallow,” I told the operator. “He’s conscious but struggling.”

“Help is on the way,” she said. “If he loses consciousness, begin compressions.”

“Copy,” I said, and I squeezed Earl’s hand. “Mr. Whitaker, can you take a breath for me? In through the nose. Out through the mouth.”

His chest fluttered like a scared bird.

The boys laughed softly, not cruel so much as amazed, like tourists gawking at weather. The tall one moved his phone for a vertical shot. “Comments are going nuts,” he said. “Three thousand watching.”

I looked up at him, feeling something in me go cold and precise. “What’s your name?”

“Why?” he said, smirking.

“Because you’re standing at the edge of someone’s life,” I said evenly, “and someday yours will have an edge too.”

He blinked. For a heartbeat, the smirk wavered. Then he turned his phone on me like I was a character stepping into his episode. “Say hi, internet.”

I didn’t. I slid the shoebox from Earl’s grip just enough to see the label. Little girls’ ballet slippers. White. Size two. I pressed it back into his hands. “I’ll make sure she gets these,” I said. “What’s her name?”

“June,” he whispered. His lips shaped the letters like a prayer. “Eight.”

“I’ll find June,” I said. “I promise.”

He tried to nod. His face tightened and then softened like wet paper. His breath hitched.

“Earl,” I said firmly, “stay with me. Look at me, not the ceiling.”

The operator asked for symptoms. I described what I saw: chest discomfort, clammy skin, dizziness. People were moving now. Two men pulled back tables. A woman took my son’s stroller and rolled it to safety, giving me a quick, watery smile like she was handing me a sword.

Security arrived first: a man in a navy blazer with a little gold badge and a calm voice. He knelt, placed two fingers to Earl’s wrist, and nodded into his shoulder radio. “EMS en route,” he said. “This way, folks, clear a path.”

The boys kept filming around his shoulder. One did a quiet sports-announcer voice: “Ladies and gentlemen, it’s getting real.”

“Stop,” I said. It came out harsher than I meant, but I didn’t soften it. “Put your phones down. If you’re going to stand this close, you’re going to help.”

“We’re helping by documenting,” the tall one said. “People need to see how malls handle emergencies.”

“This is not about a mall,” I said.

The security guard glanced up at them. “Fellas,” he said, not unkindly. “Give us space.”

“Free country,” the tall one murmured, but he shuffled back a step—just one.

Earl’s eyes slipped half shut. His hand loosened around the box.

“Sir?” the guard said, sharper now. “Sir, can you hear me?”

Earl’s head tipped to the side. The world narrowed to the small square of tile beneath him.

The operator’s voice filled my ear. “If he’s unresponsive and not breathing normally, begin compressions.”

“Copy,” I said. I placed the shoebox gently at my knee, interlaced my fingers, and found the line down the center of his chest. The hum of the mall fell away. There was only the count and the push and the tiny, human wish that effort can tug a person back.

“Thirty compressions,” the operator said. “Two breaths if trained. Keep going.”

The guard counted with me under his breath. “Twenty, twenty-one…”

The boys’ camera angles darted. One whispered, “She’s doing it. She’s actually doing it.”

“Then learn something,” the barista snapped as she slid in with a first-aid kit and a small oxygen canister. Bless that girl. Bless everyone who runs toward.

Earl’s chest rose under my hands. His face kept its waxen, determined set, like a ship’s figurehead.

“EMS in the building,” the guard reported, and the air changed—like before a storm, but softer. You could hear the wheels before you saw the stretcher, the practiced urgency of shoes that have run this race before.

“Step back, please,” a paramedic said. She was efficient, steady, hair in a tight bun, eyes kind. She did not look away from Earl as she thanked me. “Ma’am, we’ve got him.”

I slid back on my heels. My hands trembled. The boys’ cameras trembled too—suddenly the line between us thinner than I liked.

“What’s his name?” the paramedic asked.

“Earl,” I said. “Earl Whitaker. He said the word ‘dance’ and ‘show tonight.’ This is for his granddaughter, June. Eight.”

The paramedic’s mouth softened into something that wasn’t a smile but might be a promise. “We’ll try to get him there,” she said.

They worked with quiet resolve. Oxygen. Pads. A monitor chirped, sending out a signal that made the hairs on my arm lift. The guard directed the tiny crowd with low, solid phrases: “Give them space. He needs air.”

The boys drifted to the edge of the circle, eyes fastened to their screens. The tall one looked at me like he expected me to perform again. When I didn’t, he panned up to the paramedic’s hands and made a low whistle. “Comments say this is cinema,” he said softly, like a confession you make to a wall.

I stood, my knees popping. My son kicked his sneakers in the stroller, watching with his serious, solemn eyes. I tucked the blanket around him and whispered, “It’s okay. We’re helping.”

In the lift of the paramedics’ shoulders, in the way their hands did the right thing without asking permission, I remembered my father saying once, during a Midwest storm that knocked the power for a full day: There are two kinds of people—those who find the flashlights, and those who film the dark.

They loaded Earl onto the stretcher, the shoebox tucked under the straps like a second heart. As the paramedics wheeled him away, he stirred, found my hand with a weak squeeze, and whispered something I didn’t catch. I leaned in.

“Tell June the shoes are—” He trailed off. His eyes fluttered. The monitor kept chirping.

“I’ll tell her,” I said to his forehead, to the place where his life had once learned to ride a bicycle, to clock in for decades, to cheer at a school play.

The boys drifted after the stretcher like gulls behind a boat. “Stay back,” the guard said, still patient. “Let them work.”

I followed, but my reason was different. I wanted a hospital name. I wanted a destination to hang my promise on.

Outside, the sky over the parking lot was the flat silver of early winter. The ambulance lights did their polite spin. The paramedic glanced at me. “Saint Margaret,” she said. “Tell the desk you came with the gentleman from the mall.”

“Thank you,” I said. “And the box—”

“Goes with him,” she said. “Always.”

The back doors thudded shut. The world felt suddenly, foolishly quiet. Shoppers moved around us in a careful loop, like a river splitting around a rock.

The boys were still there. The tall one angled his camera, searching for a last shot. “That’s a wrap,” he murmured, as if he’d made something.

“Not yet,” I said.

He swung the phone my way. “What?”

“Did you call nine-one-one?” I asked.

He blinked. “Somebody did.”

“Did you?”

“We were… making people aware,” he said, but his voice had lost purchase on conviction.

A woman in a plaid scarf spoke up from the small ring of witnesses. “You were making a show,” she said, not unkind. “There’s a difference.”

Security took all our names in a spiral notebook. The barista brought me water. My son fell asleep like a small sunrise folding itself back into night.

By the time the police arrived to take statements, the live had already jumped platforms. You could feel it in the way strangers’ phones crackled with notifications, in the way a teen at the pretzel stand said to her coworker, “They’re saying he’s faking it,” and then swallowed that sentence like she wished it were smaller.

I told the officer everything I could. I gave him my number, the time, the little details that pin a moment down like tacks on a map. When he asked about the boys, he wrote down their descriptions with respectful, professional calm. The tall one stood nearby, jogging his knee, staring at something far away that was probably right in his palm.

“Do you know Mr. Whitaker?” the officer asked.

“No,” I said. “But I promised him something.”

I loaded my son into the car, the stroller a fussy origami in the trunk, and stared at the steering wheel until my palms stopped sweating. Then I drove to Saint Margaret, because promises make roads shorter.

At the ER desk, I said, “I came with the gentleman from the mall. Earl Whitaker. There’s a box for his granddaughter.”

The nurse on duty was tired in the way real helpers get tired—soft around the eyes, still kind. “He’s being evaluated,” she said. “Are you family?”

“No,” I said. “But I have something for family.”

I left my number and asked them to pass the message to the next of kin: June’s shoes are safe. Writing it made my breath stutter. The letters waxed and waned like they were breathing for me.

In the waiting room, the TV played a cooking show with the sound off. A man in work boots slept with his head against the vending machine. A teenage girl scrolled through a feed that ran faster than water.

My phone started to buzz. Messages from a mom group, a cousin, a neighbor: Is this you? I swear that’s your coat. Links stacked up like books in a too-small room: the live, reposted; a comment thread arguing about whether it was staged; a still image of my hands on a stranger’s chest; someone’s joke about “cardio at the food court.” The algorithm had found us, and now there was no place in the world where the air did not buzz with it.

By nightfall, a local reporter stood on the sidewalk outside the ER with a camera, making small shapes with her mouth that turned into words when the station clicked them on. She asked me to talk. I didn’t. I sent her to the officer.

I went home when the babysitter could take over, tucked my son into pajamas, and watched him dream his simple, good dreams about toy trucks and library story time. In the quiet, the day replayed—not as a clip, but as a sequence of hands. Earl’s hand on the shoebox. My hand on his. The paramedic’s hand on the oxygen mask. The boys’ hands holding rectangles. Our hands make the world what it is.

The hospital called after nine. A woman’s voice—steady, gently formal. “Mrs. Patel? You left a note. I’m Earl’s daughter, Rachel.”

“Is he—” I began.

“He’s stable,” she said. “They’re keeping him for observation. They said you… helped.”

“Your father helped,” I said. “He told me what mattered.”

She laughed in that watery way kindness brings out. “He would,” she said. “He took me to get my first recital shoes at that same store. I didn’t know he was going today. He doesn’t like to make a fuss.” She paused. “You have the box?”

“I can bring it,” I said. “Tomorrow morning.”

“June will be over the moon,” Rachel said softly. “She’s been practicing a spin for three weeks. He promised he’d be there.”

We met in the morning at the hospital cafeteria—plastic trays, a view of the helipad, coffee that smelled like a promise half-kept. June was all knees and elbows and hair like a brown river. She wore a sweatshirt with a sparkly star and hugged the box like it had traveled from a far country.

“Thank you,” Rachel said, and hugged me too, which surprised us both but felt not even a little bit wrong.

When I finally met Earl, he looked different under daylight. Less like a statue, more like a person you might stand behind in a sandwich line. He was sitting up, color back in his cheeks, the shoebox on the rolling tray like a centerpiece. His eyes were not winter anymore. They were the blue of a lake you grew up skipping stones across.

“June?” he said when she slid the shoes out. “Let’s see if they fit.”

They did. Of course they did. Some promises keep themselves.

News doesn’t travel in lines anymore; it flowers. By noon, the boys’ live had sprouted commentary from everywhere: some compassionate, some cruel, some helpful, some not. The mall issued a statement thanking bystanders. The police asked anyone with footage to share it privately for their investigation. The boys took the video down, but a dozen copies existed, sealed in the jars of other people’s feeds.

That afternoon, a man I didn’t know knocked on my door. He introduced himself as Coach Davis from Greenwood High. “One of those boys is mine,” he said simply. “Not my son. My player. I don’t want him reduced to a headline. I want him to learn how to be better.” He asked if I’d talk to his team. I said yes, because young men need the sound of women’s voices when shame makes echo chambers.

The day after that, a union friend of Earl’s reached out to the reporter and asked if they could speak on air not about blame, but about the ways people could learn to help: free CPR classes at the community center, how to recognize the signs of a heart emergency, a list of things you can do when fear freezes your feet.

By the end of the week, June did her spin on a small stage at the community rec hall. She wore the white shoes and a smile that made older men wipe their eyes with the backs of their hands. Earl sat in the second row beside me and squeezed my fingers when she landed it. He stood to clap. He did not sit back down for a long time.

You want a clean finish. You want to say the boys apologized on camera and the internet forgave them and we all learned something neat and banner-ready. Real life is softer than that. It spreads out.

One of the boys—not the tall one—came to the rec hall that night and stood near the exit with a cap in his hands. He looked like every teenager caught between yesterday’s pride and tomorrow’s sense. When the music ended, he waited for the crowd to thin, then walked up to Earl and cleared his throat.

“I’m sorry,” he said. No extras. No speech. Just those two words, said like he’d finally grown into them.

Earl watched him, quiet. He could have said a dozen things. He chose the one that leaves a door cracked.

“Carry a flashlight,” he said gently. “Next time the lights go out.”

The boy nodded like a person nods at an instruction that will take a lifetime. He left, shoulders hunched, hat twisting in his hands. I don’t know if the others came around. Maybe they will when the world presses on them in the same way and they find out a phone screen is a poor shield against real weather.

I do know this: in the weeks after, the community center’s CPR class filled and then filled again. The barista and the security guard both signed up to teach. The mall’s maintenance team added a new AED unit and put a sign under the skylight reminding people where it is. Saint Margaret put a flyer by the elevators that said in large letters: If you see something, say something, and if you can, be the one who steps forward. The font wasn’t pretty. It didn’t need to be.

As for Earl, he made it to every one of June’s rehearsals. He wore a cap from a steel plant that shuttered the year she was born and clapped like he was paying off a debt with joy. When the reporter asked him on a follow-up segment how he felt about the boys, he thought for a long time and said, “I don’t want anyone’s worst minute to be the only thing the world knows about them. But I also want their worst minute to teach them how to make a better one.”

That line traveled far. People turned it into a graphic with a sunset behind it. Someone put it on a mug.

Months later, I ran into the tall boy in the grocery store, aisle seven, beside the cereal with cartoon mascots. He looked surprised to see me and then something else—maybe relieved. He said his name. He said he’d taken the class. He said he’d stopped a man from choking at a barbecue by doing the Heimlich, and the man hugged him with surprise and ketchup on his shirt. He told me he’d turned off his lives for a while to figure out who he is when there’s no blinking red dot.

“That’s a good place to start,” I said. And I meant it.

Sometimes I think about the first minute, the one where nobody moved. It would be easy to make that minute the headline for the whole story. But that minute isn’t how it ends. It ends with a shoebox in a little girl’s hands and with a man whose heart kept its beat because a dozen strangers found something inside themselves and brought it into the light.

When I tuck my son in now, he asks sometimes: “Is the shoe grandpa okay?” He means Earl, of course. I tell him yes. I tell him there were helpers. I tell him he can be one.

On Sundays, if you drive past the community center, you can see a line of folks going in for a class that teaches palms to press down, lungs to fill up. There’s a rhythm to it you can hear if the door is open—a steady count, and then a breath, and then hope.

And if you happen to walk through Greenwood’s mall on a winter afternoon, you might notice a small plaque under the skylight where the light spills like blessing: In honor of the people who stepped forward, and for the ones still learning.

The world is full of screens and feeds and loops that blur the edges of our days. But every now and then, the noise thins, and you see the simple shape of a person in need and the equally simple shape of a person bending toward them. It isn’t complicated. It isn’t even heroic most of the time. It’s a hand, outstretched. It’s a shoebox held tight. It’s a breath that keeps going because somebody else decided to count.

Three teenagers went live while a grandfather collapsed in the food court. Thousands watched. For a full minute, no one moved.

And then—someone did.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta