Part 1 – The Key on the Casket

“Tell the ushers to stop him at the gate if he shows up in that leather jacket,” I told the church coordinator, tapping the glossy guest list with my polished nail. “This is my father’s funeral, not a parade.”

My name is Nora Hale. I argue for a living and win more than I lose. I color-code my files, iron my shirts, and never miss a deadline. I also haven’t spoken to my older brother Evan in six years.

“Mom?” I looked over my shoulder. Ruth sat in the last pew like she always did—near the aisle, hands folded, eyes on the stained glass. She wore the navy dress Dad liked and the little silver locket he gave her when Riverbend still had three factories and a marching band on Friday nights.

She didn’t answer. She didn’t scold me. She didn’t defend him.

The sanctuary smelled like lilies and lemon polish. People I barely knew shook my hand and whispered the same sentence: Your father did so much for this town. Out the tall arched windows, the sky was that pale, winter blue that tricks you into thinking it’s warm.

When I glanced toward the parking lot, I caught the dark shape of a motorcycle at the far curb, engine idling low. Another rolled in beside it. Then another. The riders didn’t crowd or stare through the glass. They lined up along the street and turned their handlebars inward, neat as a color guard. Helmets tucked under arms. Gloves folded into back pockets. Not loud. Not showy. Just there.

“Don’t look,” I told my fourteen-year-old, Liam, as if I could keep curiosity on a leash.

He looked anyway. He’s good at engines, my son—too good. He can hear a misfire the way other kids hear off-key notes. I tell myself it’s because he’s bright, not because he got it from Evan.

“Mom,” he whispered, “that’s Uncle Ev—”

“Don’t,” I said too quickly. “Not today.”

The organ started. The ushers lifted the casket. People stood. I watched the edges of everything: the hem of Karen’s black dress, the shine on Michael’s shoes, the white linen on the altar. Watching edges is how you avoid the center. The center today was a wooden box that held the man who built our house by hand and never cried in front of anyone, not even when the plant shut down and Riverbend turned quiet.

My mother rose slowly. She wobbled, caught herself on the pew, then reached into her purse and pulled out an old leather jacket—brown, softened by years and sun. My father’s. The one he stopped wearing after his title changed from Foreman to Manager.

“Put that away,” I whispered, startled. “Someone will think—”

“They already think,” she said calmly, her voice a thin thread. She held the jacket to her chest, then flipped the lining and slid something into my palm: a small ring of keys bound with a frayed bootlace. Every key had a tiny metal tag, hand-stamped with numbers and letters. Some tags had names. Some had places. One just said RIVER.

“What is this?” I asked.

“Promises,” Mom said. “Your father’s. Your brother’s. Mine.”

“Mom, I don’t—”

“If you want to know why your brother stood outside more Sundays than he came in, open what these unlock,” she said. “Open them before you close anything else.”

I stared at the keys. They were warm, as if they had been held. The tags chimed against each other, a soft sound under the organ’s swell.

The service blurred the way long days do. People stood and spoke in careful phrases. The mayor told a story about Dad finding him on the roadside with a flat tire and changing it in the rain. A woman from the clinic said someone had been leaving envelopes at the front desk for years—no return address, just a note that said, “For the copay.” She looked at me when she said it. I looked away.

When the final hymn rose and the ushers turned toward the aisle, I felt Liam shift beside me. He wasn’t crying like the children two rows up. He was perched forward like a runner in blocks.

“Don’t,” I murmured again, but my voice didn’t reach him.

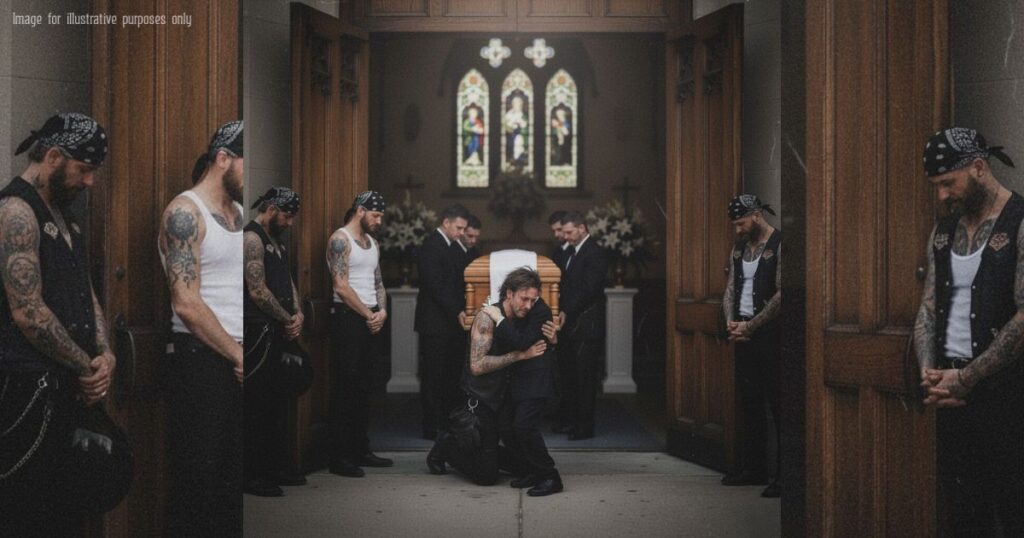

As the casket passed our pew, the front doors swung open, and sunlight flooded the center aisle. Everything went bright, then sharper, like the world had clicked from standard to high-definition. Evan stood framed in the light, helmet tucked under his arm, hair wind-mussed, jaw unshaven, eyes steady. He didn’t step in. He didn’t make a scene. He just removed his gloves, one finger at a time, like he was untying a knot.

Liam slipped from my hand and moved toward him before I could stop him.

“Liam!” I hissed, catching only air.

My son reached the threshold. Evan dropped to one knee without thinking—like he’d done it a hundred times. Liam wrapped both arms around his neck. The hush that fell wasn’t the polite kind. It was the kind that listens.

“Hey, kiddo,” Evan said, soft. The word landed between their foreheads like a peace offering. “You okay?”

Liam nodded into his shoulder. “I told you I’d come,” he whispered, and my stomach went cold. Told him?

Evan looked up then, across the pews, across the flowers, across the last six years. Our eyes met, and all my practiced speeches crumbled. He didn’t look angry. He looked tired and… unsurprised. Like he’d been waiting for this moment to hurt and finally let it.

He stood, walked to the casket as it paused at the door, and did something I will not forget as long as I live. He set a single key on the polished wood—an old brass one with a nick on the bow—then stepped back and folded his hands.

The tag on that key matched one in my palm.

RIVER.

Behind him, along the curb, the riders removed their helmets in unison. No engines revved. No heads turned for the camera phones I suddenly noticed. Just a line of people who had arrived and were willing to wait in silence while a family decided what kind of family it wanted to be.

“Mom,” Liam said, his voice trembling as he returned to my side. “Please don’t make me pick between you and him.”

“I’m not—” I started, then stopped. Because maybe I had been.

My mother touched my elbow. Her fingers were cool. “Keys only work if you’re willing to try the lock,” she said.

The ushers moved through the doors. The sunlight held. The key on the casket caught it and flashed.

How does my son already know the man I told security to keep outside?

And why, after all these years, does my father’s jacket lead straight to my brother?

Part 2- RIVER: The Room That Stayed Ready

I didn’t follow the hearse. I followed the key.

After we stepped out into that cold, clear noon, after hands were shaken and casseroles were promised, Mom nudged the leather jacket against my arm like a conspiracy. “RIVER first,” she said. “Before you talk to anyone else. Before you decide anything else.”

Evan didn’t say a word. He only pointed two fingers toward the road, a silent question. Liam looked from him to me, pleading without opening his mouth.

“Forty minutes,” I told the coordinator who kept trying to herd us to the family cars. “Tell them we’ll meet at the house.”

We didn’t. We turned toward the levee.

River Storage was a row of low concrete mouths along the water, each with a corrugated door the color of a storm cloud. A faded sign swung on rusty chains: NO BOATS INSIDE. NO GAS CANS. The office window had a CLOSED sign that had probably earned its retirement five years ago. Gulls bit at the wind. The river moved like it had somewhere to be.

Evan arrived first, his bike purring into hush and then into silence. He took off his helmet and leaned it on the seat like it belonged to someone else. He didn’t reach for the key in my hand. He looked at me, then at Liam, then at the row of doors as if checking them for heartbeat.

The tag said RIVER, but the keys all looked the same, old brass and nickel with teeth worn a little thin. I tried one. It scraped and stuck. I tried another. It turned and refused. The third slid in and caught. When I twisted, something inside the lock sighed like lungs unclenching.

The door fought me halfway up and then rolled back with a rattling clatter that bounced around the concrete hallway. Cool air spilled out—river damp, rubber, a memory of hot metal and oil.

It wasn’t what I expected, which I think is the first honest sentence I can write about that day.

No crates of parts dumped in a heap. No pinup calendars from another era. No flag on the wall to make a point. The left side was lined with shallow shelves that someone had sanded smooth and painted the color of schoolroom chalk. On the shelves: small helmets. Dozens. Scuffed and stickered, some with names in block letters, some with stars drawn by unsure hands. Tiny elbow pads stacked like soup bowls. A plastic bin of replacement visors. Ziplock bags of earplugs.

The right side held milk crates full of brake pads, spark plugs, reflective stickers still in their packaging. A row of orange vests hung from hooks, each with a Sharpie name on the inside tag. A wheeled toolbox sat in the back with drawers labeled in a neat, assertive print: WRENCHES – METRIC. WRENCHES – SAE. LIGHTS. TAPE. FIRST AID (BASIC). On top of the toolbox lay a clipboard. The top sheet was a grid: Date, Miles, Gas, Reason. The column under Reason read like a town whispering: “Night shift – radiator hose split.” “Clinic copay.” “Baby seat check.” “Graveyard tire.” “Interview – needs clean shirt, size L.” Some entries were initialed E.H., some simply H., some M.R. or P.C. There were a lot of initials. It was a crowd, but one that knew each other by first letters.

“Wait,” Liam breathed, stepping toward the helmets, fingers hovering like he was in a museum. “These are all kids’ sizes.”

“Some are,” Evan said, voice low. “Some are for short rides around a parking lot. Some for rides on the back with a parent who can’t afford to replace the one that cracked last year.”

I picked up a helmet that had been stickered with yellow lightning bolts and a shaky name: JAY. The chinstrap was frayed from being tightened by impatient fingers. “Whose is this?” I asked, not sure who I was asking.

“Belonged,” Evan said. “Past tense. They outgrow them. We pass them on.”

I set it back carefully, as if someone were asleep inside.

Taped to the wall above the toolbox was a hand-painted sign on a piece of cardboard, white brushed over the shipping words and then stenciled neat: IF YOU BORROW, RETURN. IF YOU CAN, LEAVE ONE. The last line had been added later in a different hand: IF YOU’RE NEW, WELCOME.

My throat hurt. It didn’t make sense, but it did, the way a picture snapped into focus only after the photographer had already walked away.

“You ran this?” I asked, because my brain knew how to cross-examine even when my heart was trying to learn a different language.

Evan shook his head. “We kept it open,” he said. “Different people covered different hours. Your old principal kept the spreadsheet on her phone. Mr. Delgado down the block did the sharpening. A nurse from the clinic checked straps and wrote down sizes. Reverend Cole brought coffee and told bad jokes when it got cold.”

“Dad?” The word left me before I decided to let it go. He was everywhere in the air—every clean shelf, every bracket set flush to the block, the stern, tidy insistence on labels. He could not be nowhere in this room.

Evan’s mouth moved like he was choosing careful words. “He used to stop by,” he said. “Said a place is only as decent as what it does when no one is watching. Said that before he said other things.”

The clipboard under my hand flipped when I reached for another page. Below it was a tear-off desk calendar, the kind you rip to give time a rhythm. A blue pen had crossed each day with an X, sometimes straight, sometimes slanted, sometimes bold, sometimes a tired lighter stroke. In the corner of some days was a note: LATE SHIFT, LIAM’S LESSON, CLINIC. The Xs marched forward month after month, a line that felt like footprints.

They stopped.

Not at the last page. Not at a holiday. They stopped on a thick dark X two-thirds through a year I didn’t expect—2019. Beside that X was one word, printed hard enough to press through to the page beneath.

PRESS.

The hair on my arms lifted. The plant had a press line, of course it did. Big machines that swallowed sheets of steel and gave back parts that made other things possible. When the plant shut down that fall, the rumor mill invented a dozen reasons: bad orders, bad loans, bad luck. Our house swore it was “market forces.” Other houses swore it was everything else.

“Why did you stop?” I asked, but I wasn’t looking at Evan. I was looking at the box of reflective stickers, a cheap safety blanket for people who wanted to be seen, and thinking how many nights Riverbend had felt invisible.

Evan didn’t answer. He was examining a tiny scuff on the corner of the toolbox like it mattered more than my question. Liam went very still, which is not something fourteen-year-old boys do when they’re in a room full of gear.

“Did Dad shut it down?” I pressed. “Did you fight? Did someone complain? Did the city—”

“Sometimes,” Evan said finally, “you stop because the story you’re telling can’t carry one more secret without breaking.”

I turned toward him. “That’s not an answer.”

“It’s the one I have,” he said. He looked tired again. He looked like that key had been heavy in his pocket for years.

Footsteps scraped in the hallway outside, a gentle shuffle that sounded like Sunday shoes. Mom appeared in the doorway, hair coming loose from its pins, the leather jacket folded over her arm. “I knew you wouldn’t wait for me,” she said, and there was something like approval hiding in her scolding.

She took in the room with one sweep of her eyes, and I watched something unclench in her shoulders. “He kept it neat,” she said. I didn’t ask which he she meant.

“Why keep it a secret?” I asked, the prosecutor’s rhythm all over again. “Why not… post a sign or put it in the paper? Raise money. Ask for volunteers. Why run charity like a spy ring?”

Mom shook her head. “Charity can make people feel small,” she said. “This was neighbors. Borrowing isn’t begging, Nora. It returns what it can.”

I could feel my spine resenting that answer, even as the rest of me warmed to it. “And the day it stopped?”

Mom glanced at the calendar. Her fingers flinched, once, then settled. “The press jammed,” she said. “The machine ate its own rhythm, like machines do when the paper says they shouldn’t. It wasn’t… awful,” she added quickly, as if she could head off the pictures shuttering through my head. “But it was enough. People were afraid. Rumors got loud. A good place got scared of itself.”

“Dad got scared,” I said before I could catch the sharpness.

Mom looked at me like I was a photograph she’d taken when I was five. “Your father wanted to be the kind of man who never flinched,” she said. “He was human instead.”

Evan put the calendar back, smoothing the curled corner like a nurse tucking a blanket.

Liam had wandered to a plastic crate labeled LIGHTS. He picked up a small battery pack and clicked it. A soft white glow lit his face from below, and he grinned in spite of himself. Then he saw me watching and his smile went careful. “Uncle Evan says you should always check your lights before you need them,” he said, wary, like he was testing the ice.

“You’ve been here,” I said, not a question.

Liam swallowed. “On Saturdays sometimes. In the lot. Just to learn. Mom, it’s safe. It’s supervised. They make you walk before you ride.”

The hallway outside carried a distant radio—static, then a DJ cheerfully announcing traffic somewhere that wasn’t us. It sounded like another country.

I looked at my son holding light in his hands like a brand-new idea. I looked at my brother who would not defend himself because defense would require pointing at other people’s mistakes. I looked at my mother, who had chosen, for reasons I still did not like, to carry a weight I didn’t know how to name.

On the clipboard, the last complete line before that dark X read: “Clinic copay – returned with thanks.” The initials were E.H.

“Evan Hale,” I said.

Mom’s mouth curved, sad and amused. “Or Edward Hale,” she said softly. “Your father never corrected anyone when they assumed a helper’s name.”

The room rearranged itself without moving. The shelves and the bins and the neat labels made a new kind of sense that felt like standing at the top of stairs in the dark and knowing there’s one more step.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked Liam, and immediately hated how small that sounded.

“Because you already decided,” he said, and his voice wasn’t cruel, just true. “I didn’t want you to pick for me before I understood what I was picking.”

Evan scrubbed a hand over his jaw, like he wished he could erase the whole day and keep the parts that mattered. “Nora,” he said, and my name in his voice was a room I had moved out of years ago, “there are other keys.”

He was right. The ring in my palm was heavier than when we’d arrived. LIB, PARK, WHARF, SHOP, and one tag stamped with a number I didn’t recognize.

I slid the calendar pages forward with my thumb. Past the thick X. Past the blank squares. Farther. There were no more marks. The days had kept marching, but the hand that had crossed them had set the pen down.

“What stopped this?” I asked again, softer this time, as if a different tone could coax a different truth. “Not the machine. Not the rumor. What stopped you?”

Evan stared at the tiny helmets for a long time. “Something broke,” he said at last, “that we couldn’t fix with a wrench.”

He didn’t mean metal.

I turned the keys over. The tags chimed like wind chimes in a storm that hadn’t decided if it would arrive. Outside, the river kept going, unbothered by our calendars.

I closed the roll-up door halfway and looked at the people who had become my puzzle. “Then we open the next lock,” I said.

Evan nodded once.

Liam slid the light into his pocket and stood straighter, like a boy invited onto a team he’d watched from the bleachers.

Mom tucked the leather jacket closer to her ribs, like she was listening for a heartbeat in old hide.

Behind us, on the clipboard, the last word on the last line stayed where it was, a small courage written in blue ink: returned.

We stepped back into the daylight, and I did not lock the door.

Part 3- LIB: Cabinet C — Borrow, Return, Welcome

I drove to the library because the key told me to.

LIB, stamped crooked on a thin tag, pressed into my palm as if it had an opinion. Riverbend Public sat like it always had—red brick, white columns, a set of concrete lions whose noses had been rubbed smooth by generations of bored children. The flag lifted and fell in the light wind. On the bulletin board by the entrance, flyers pitched tutoring, flu shots, a community cleanup. Someone had taped a handwritten note over a torn corner: Please return puzzles with all pieces. The small rules of a town that still wanted to work.

Inside, the world softened. Carpet swallowed footsteps. Dust fell in sun-slants like slow glitter. The air smelled like paper and glue and the particular patience of librarians.

“Ms. Parker?” Mom called quietly, although the sign already asked us to. She’d put Dad’s leather jacket over her arm again, like a memory you didn’t trust to a hanger.

A head popped up from behind the circulation desk—gray bob, reading glasses on a beaded chain. “Ruth.” Ms. Parker’s face warmed and then rearranged itself when she saw me and Evan together. “Nora. Evan.” She nodded like she was processing three weather reports at once. “I watched the service online,” she added with a small, gentle shrug. “Clumsy camera work. Beautiful hymn.”

“We, um,” I began, holding up the key like a hall pass. “We need the downstairs storage. Cabinet C.”

She didn’t blink. She reached beneath the counter, pulled out a ledger with a cracked spine, turned it to a page that had the year written in blue marker. Her finger ran down a column of names until it landed on H—Hale, Ruth. Then H—Hale, Edward. Then H—Hale, Evan. The entries went back years.

“You kept track of this?” I asked, surprised by how proud my voice sounded of a thing I hadn’t known existed.

“We keep track of all the important stuff,” she said, and nodded toward Liam. “You’re taller.”

“I know,” he said solemnly, as if he’d had anything to do with it.

We followed her through a STAFF ONLY door that had forgotten how to be intimidating. The stairwell was lined with old summer reading posters: “Find Your Treasure (Under the Sea of Books!),” “Read to a Dog,” “Adventure Awaits.” At the bottom, a cool basement spread out with metal shelves and rolling carts. It was orderly in the way Dad liked things, which hurt and helped in equal measure.

Cabinet C was a four-drawer steel unit with dented corners and a sticker that said PLEASE LABEL BEFORE RETURNING. Ms. Parker stepped back and made a little show of not watching me use the key, the same way a good neighbor pretends not to see you count the cash you owe them.

The lock turned like it had been waiting for exactly this hand.

Inside, the top drawer held folders arranged so neatly they were almost a whisper. Each tab was labeled in that assertive print again: COPAYS, RIDES, GEAR, JOB INTERVIEWS, MISC. There were receipts with corners rubbed soft, stapled to notes written in a dozen hands. There were thank-you cards from children full of exclamation points and threes written backwards. There were notes that simply said, Paid back, with a five-dollar bill paper-clipped to the edge, and others that said, Can’t yet, with a small drawing of a heart.

“Why here?” I asked, leafing through a folder. Gas cards. Bus passes. A typed sheet with bold instructions on how to adjust a child’s helmet so it sat level and safe. “Why the library?”

“Because people can walk in without explaining themselves,” Ms. Parker said. “Because we already believe in quiet. Because not everybody wants a photograph every time they need help.”

Evan touched a stack of tear-off forms labeled RIDE REQUEST. The form asked only for first name, destination, and a preferred time window. At the bottom: NO QUESTIONS ASKED. Liam traced the words with one finger like a kid trailing his hand along a fence.

The second drawer held clipboards and a plastic tray of pens that had been tested and put cap-forward. Beneath them, a cigar box without cigars, full of tiny index cards—sizes for elbow pads and helmets, written in blocky pencil. Someone had drawn a line of stars along the bottom of one card; another had a greasy fingerprint in its corner like a signature.

The third drawer was heavier. When I slid it open, something clinked: old coffee cans with taped-on labels—QUARTERS, FUSES, PATCHES. There were tiny things that keep bigger things from failing. There was a manila envelope flat with seriousness. I opened it carefully. Inside: photocopies of a permit application for a small neighborhood “practice lot” to be used on Saturday mornings, with a diagram of cones and arrows and STOP printed in big block letters. A sticky note, its glue exhausted, had been tucked inside: “Try again next month. Budget meeting ran long.” Initialed E.H.

“Evan?” I said, looking up.

“Could be me,” he said, then tipped his head toward Mom’s jacket and then up—where Dad sat in the ceiling we could not see. “Could be him.”

The fourth drawer resisted and then gave, revealing a shoebox with a lid covered in contact paper patterned with tiny daisies. The tape made a soft tearing noise in the quiet basement. Inside were letters, the kind people write when they aren’t posting for anyone. I glanced at Evan; he lifted his hands as if to say, You choose. I chose one with crayon on the flap.

“Dear whoever helped us with the clinic,” it began, printed large. “My mom says it was an angel, but Ms. Parker said angels come disguised as neighbors. I drew you a picture of our bike. The light works now. Thank you for making us safe. Love, Jay.”

The JAY on that page looked like the JAY that had been on the helmet at the storage unit. My throat had the same ache it had when I walked into a courtroom and realized the person on the other side was not a villain but a person.

Ms. Parker watched me reading, then pulled another envelope from the shoe box and slid it across the cabinet top. “This one is for you,” she said to Mom.

It was addressed in Dad’s cramped script. Ruth—Library—Cabinet C. Mom set the jacket down and opened the envelope with her thumb like she had done it a hundred times. Inside was a short note on a torn half-sheet of ledger paper.

“Keep the cabinet as long as Ms. Parker will let you. If the town gets loud, close the top drawer and open it again when it’s quiet,” she read, and her voice didn’t break until the last line. “If Nora asks where I am, tell her I’m trying to be of use.”

I looked at the cabinets, at the stacks of things that mattered because they were small. Because they were the sort of objects you could hold and not feel owned by. The kind of help that didn’t brand you when you carried it home.

A vibrating buzz rattled in my pocket—my phone, nudging like a mosquito you can’t swat in a sanctuary. The screen lit up with a text from my boss. Saw clip of the bikes at the church. Are you able to make a statement? Something graceful about safety and the need for order? My skin prickled, that old familiar urge to manage optics rising like a reflex. I slid the phone face-down on the cabinet and let the basement breathe.

“Mom,” I said, “how much of this did you do? How much did Dad ask you to do? How much did Evan…?”

“It wasn’t a ledger,” she said simply. “We don’t get points. We get neighbors.”

“It could have been a program,” I argued, because arguing is my resting heart rate. “We could have made it official. Grants. Logos. Press releases.”

“And then people would bring their pride through a different door,” Ms. Parker said. “The door marked ‘Applicants.’ This one says ‘Readers.’”

Liam shifted from foot to foot like a runner waiting for a baton. “Can I—” He stopped, checked my face, tried again. “Can I help? On Saturdays, I mean. With the practice lot if you ever get the permit. Uncle Evan says the first lesson is how to stand a bike up without hurting your back. I could teach that. I learned it last week.”

“Last week,” I echoed, dry. “Between algebra and chores?”

He winced and put both hands flat on the cool edge of the drawer. “I should have told you,” he said, and I could hear the apology he wanted to hand me. “I didn’t want you to say no because of what you think when you hear an engine.”

“I think of you,” I said, and felt the truth of it in my ribs. “I think of you and I can’t hear anything else.”

Evan cleared his throat. “Politics are coming,” he said softly, like weather. “They always do when something quiet turns out to be bigger than folks thought.”

“Then we anchor it,” I shot back, sharper than I meant. “We anchor it to good records and names on forms and a policy that says exactly who we are and aren’t.”

“And we keep a drawer for the people who won’t walk in if there’s a policy,” Ms. Parker said, not sharp at all. “The world can have both.”

We stood there like a small committee in the cool basement, three versions of the same family staring at stacked proof that somebody had been paying attention while the rest of us were busy being important.

I reached for one more file. It was thin, nearly empty, labeled MISC. Inside: a page torn from a legal pad with a list written in two hands. The first hand—firm, tidy—said: Cones: 24. Chalk: 3 sticks. Vests: 8. The second hand—larger, loopier—had added: Water jug, Band-Aids, string. At the bottom, there was a Polaroid tucked under the clip.

It had that dreamy light that old instant pictures get, colors a little washed, edges a little soft. The scene was a parking lot outlined by white chalk arrows. Cones, small in the frame, marched like sunset-colored soldiers. A boy in a helmet too big for him was concentrating on a balance drill, one foot down, one hand steady on the bar. On the left side of the frame stood Evan, younger, hair too long for a courtroom and exactly right for the wind. On the right stood my father.

He was wearing the brown leather jacket.

Not draped over his arm. Not slung over a chair. Wearing it. Zipped halfway. The collar turned up like he’d been chilly. His hand was on the boy’s shoulder in a way that knew where to put weight and where not to. His face was caught mid-sentence, mouth just open, eyes almost smiling. He looked like a neighbor, not a title.

My throat closed around something I didn’t know how to swallow.

“Date?” Evan asked, leaning in.

The white margin had the neatest handwriting I’d seen all day: 10/12—PRACTICE LOT—EARLY.

“Before the press,” Mom said quietly. “Before a lot of things.”

I stared at my father’s jacket in the photo and then at the jacket folded over Mom’s arm. The leather in the picture had the same scuff on the left pocket, the same crease where a wallet had lived too long. The man in the picture had a softness I couldn’t remember on purpose.

“Why would he—” I began, and didn’t finish, because there were too many possible endings. Why would he help and hide? Why would he stop and stay stopped? Why would he look like this in a parking lot and like something else at our dinner table?

Upstairs, somewhere, the front door opened and closed. The sound traveled down the stairwell like a reminder that the public was still above us, checking out mysteries and paying fines and printing resumes in black and white.

I slid the Polaroid back into the folder and closed the drawer gently, as if quiet could keep the picture from fading.

Behind me, the key ring chimed in my hand. It sounded like a question.

If my father was willing to wear that jacket when no one was watching, who exactly had I buried this morning? And if my brother had been the hinge between who Dad wanted to be and who he could be, what did that make me?

Part 4- SHOP: A Room That Tells the Truth Quietly

The next tag on the ring was stamped crooked: SHOP.

Evan didn’t ask if I wanted to go. He turned his bike toward the old municipal garage on Maple—the low brick building with three bay doors and a tin roof that pinged in summer. The city parked snowplows there once, back when winter came with proper drama. Now a faded banner hung crooked over the middle door: COMMUNITY CARE—THANK YOU, VOLUNTEERS. The thank-you looked accidental, like the wind had put it there.

I slid the key into the side entrance. The lock turned with the same relieved sigh as the storage unit, as if a set of lungs had been waiting right behind it.

Dust hung in the air like it had nowhere else to be. Light poured through high windows and made ladders on the concrete floor. The place was cleaner than any “abandoned” building had a right to be—swept lines, tools returned to their outlines on a pegboard, a broom leaned with dignity in the corner. Someone had taped a strip of painter’s tape under each outline and written the name in tidy print: HAMMER, METRIC SOCKETS, TIRE IRON, ZIP TIES.

And on the back wall, a wide plank of reclaimed wood had been sanded and stained. A row of hooks ran across it, each holding a single key on a tag. The tags matched the ones in my palm—small, stamped with places and initials. Under the hooks, someone had burned a line into the wood with a pyrography pen:

IF YOU NEED A WAY IN, TAKE ONE. RETURN WHEN YOU CAN.

I felt the weight of the ring in my hand like it wanted to answer.

Liam broke the silence first. “This is where we met on Saturdays,” he said, then flinched, waiting for me to correct the tense. “We. They. People.”

Evan rested his helmet on the workbench and kept his hands in plain sight, as if even in here he didn’t want to look like he was taking up too much room. “Parking lot drills when the weather’s good,” he said. “Inside, if it rains. How to stand a bike without hurting your back. How to see and be seen. How to know when a machine is telling you the truth.”

“Machines do that?” I said, because sarcasm was easier to reach for than awe.

“They do if you listen before it’s loud,” he said.

On a corkboard near the office door, someone had drawn a map of Riverbend with chalk—our grid of streets, the crooked river, the library, the clinic, the warehouse district. Little Xs marked spots, each with a tag name. RIVER. LIB. WHARF. PARK. SHOP. It looked less like a treasure map than a circuit—nodes connected by thin lines. Not one hero. Many small currents.

Mom ran her hand along the plank of hooks, not touching the keys themselves. “He hated when things went missing,” she murmured, meaning my father and also not meaning only him.

“He liked when they went somewhere on purpose,” Evan said.

A bright orange square on the office door broke the steady color of the room. CITY NOTICE, it announced in serious block letters. UNSAFE STRUCTURE—NO OCCUPANCY WITHOUT INSPECTION. A date from last month was stamped at the bottom. There was a box for “reason” with a check next to REPORTS OF CROWDING.

“Since when?” I asked, pointing.

“Since exactly when you’d expect,” Evan said. He didn’t look angry. He looked like he was trying to be fair even to a piece of paper. “Someone called. Said too many people were in here at once. Said it wasn’t official. Said it looked like… gatherings.”

“Gatherings,” I repeated, tasting how ominous the harmless word could be. “Were you over capacity?”

“We keep the doors open,” he said. “We keep headcounts. We teach outside whenever we can. But a photo from the wrong angle can make any room look full.”

A voice drifted in from the doorway, warm as a hymn sung off-key and better for it. “And a rumor from the wrong mouth can make any good thing look dangerous.”

Reverend Cole stepped in, hat in his hands, the cold clinging to his coat. He nodded to Mom, then to me. “I brought coffee out of habit,” he said, lifting a cardboard carrier with three cups and an empty spot where a fourth had been. “Then I remembered the city thinks hot drinks summon chaos.”

“Hello, Reverend,” I said. “Do you have a key, too?”

He smiled, eyes crinkling. “I borrow one,” he said. “From whoever will remind me to return it. This place is a room that tells the truth quietly. We don’t have many of those.”

He set the cups on the workbench and moved to the chalk map, tapping the corner that said PARK. “We’ve been drawing circles,” he said. “People don’t always have cars. They do have legs. If we put the cones and the vests at the edges of town—library, wharf, park, river—families can reach one or another in ten minutes. We take the teaching to them. We don’t make them carry their need all the way here.”

“That was the idea,” Evan said, not claiming it, just naming it.

Something in my chest tugged, like a knot wanting to loosen. “You could have told me,” I said, and I didn’t know if I meant Evan or my father or both.

“We tried telling with objects,” Reverend Cole said, gentle, turning over a reflective sticker until it caught the light. “Sometimes stories don’t trust words at first.”

He wasn’t wrong. The room spoke in evidence—cones stacked in a neat pyramid; a tub of chalk powder labeled DO NOT BREATHE; a photo taped to the pegboard of a conga line of tiny bikes following a line of arrows drawn on asphalt; a milk crate full of lights with fresh batteries; a box of clean T-shirts still in plastic with sizes written in marker. On the office desk, a rule printed in bold sat under a paperweight: NO PHOTOS OF CHILDREN. NO EXCEPTIONS.

I ran my thumb over the edge of the orange notice until it bit. “We can fix this,” I said. “Permits. Occupancy. Liability. I know the language. I can help you go from ‘room that tells the truth quietly’ to ‘room the city can’t shut with a stamp.’”

“And keep a corner that stays quiet,” Reverend Cole added, a statement more than a question.

“I can try,” I said. For a second I saw a version of myself I hadn’t met—the version who writes policies that protect what matters rather than boxes it up and drains it.

Liam was at the plank of hooks, reading each tag silently, lips moving. He pointed at one that had only numbers: 14-33. “What’s that?”

Evan looked at Mom. Mom looked at the floor like something interesting had spilled there. “That’s for the box under Dad’s old desk,” she said finally. “At home. He kept it for notes that weren’t ready to be notes yet.”

I filed that away with the library Polaroid and the calendar in the storage unit and felt the shape of a story lean toward the front of my mind. It wanted to be told. It wanted not to hurt anyone in the telling, which is not always possible.

Outside, a white SUV rolled to the curb. The city seal glinted on the door. A man in a puffer jacket and a clipboard got out, moving the way people move when they’re trying not to be the villain in someone’s day.

He lifted a hand, palm out. “Just an observation,” he said from the threshold. “No citations today.”

“We’re closed,” Evan said mildly, gesturing to the sign like it could do the conversation for him.

“I can see that,” the inspector said. He peered in, eyes skating over tools and cones and faces. “We had another call.”

“From who?” I asked, too sharp.

He wrote something on the clipboard that might have been real or might have been a way to look busy while not answering. “Says the place draws crowds. Says folks are uneasy after… you know.” He meant the funeral, the engine line outside the church, the video that had started to make its clumsy way through town feeds with half the context.

Reverend Cole stepped forward. “Officer, you are welcome to observe any Saturday you like. You’ll see more caution than noise.”

“I’m not an officer,” the man said reflexively, then eased. “Look, I don’t decide what’s allowed. I check boxes to keep people safe and to keep my supervisor from calling. We’re all surviving our clipboards.”

He slid a red tag into a plastic sleeve under the orange notice. REINSPECTION SCHEDULED. He nodded to us all, kind without being friendly, and left the door open a moment too long so the cold could make a point before he closed it.

When the SUV pulled away, the building exhaled. The orange and red notices fluttered like flags on a breeze that didn’t reach us.

I turned to Evan. “Let me file the paperwork,” I said. “Let me walk this through the boring way. Headcounts. Occupancy. Insurance riders. We’ll need a fire extinguisher inspection and a proper first-aid kit and—”

“We have a first-aid kit,” Liam said, a little offended on behalf of Band-Aids everywhere. He lifted a red case from under the bench and set it down, proud. “Labeled. And the expiration dates aren’t weird.”

“I’m not doubting you,” I said. “I’m asking the city to stop doubting you.”

Evan watched me the way you watch a bridge you’re not sure has been tested. “Make it official without making it fragile,” he said. “If you can do that, I’ll learn how to like clipboards.”

“Deal,” I said.

I stepped outside to call my office—my version of grabbing a wrench—and the wind slapped color into my cheeks. The inspector’s SUV had left tracks in the gravel. My phone buzzed again: a local forum link pulsing with urgency. Did you see what happened at St. Mark’s? Some posts were kind. Some were not. A photo from a bad angle made the riders look like a wall instead of a line with space between. It is not hard to turn any act into its shadow if you crop it right.

A white envelope was tucked under my windshield wiper, the cheap kind with the peel-off strip. No stamp. No return address. Just my name in block letters that were trying very hard not to look like anyone’s actual hand.

I slid a finger under the flap, tore it open, and read.

STOP DIGGING. RIVERBEND NEEDS A CLEAN STORY.

No threats. No signature. Just that—like a memo from a board I hadn’t agreed to sit on.

I stood there with the letter in my hand and the building at my back and the smell of coffee sneaking through the door and wondered who in a town this size could be both nobody and everybody enough to write a sentence like that.

I looked up at the high windows where the light made patterns and thought of the jacket at Mom’s elbow, the calendar X, the Polaroid of my father in brown leather, smiling quietly at a boy learning balance in chalk lines.

Who needs the story to be clean?

And what gets washed away to make it look that way?