Part 1 – Dragged Into the Sun

An old veteran dropped beside the cereal aisle clutching his chest; five phones went up to film, one manager grabbed his arms, and I heard my own voice ricochet across the polished tile: “He’s not drunk. He’s dying.”

By the time the AED said “analyze,” the sun outside was a furnace, and a decision made in five careless seconds would haunt everyone standing there with their cameras up.

My name is Nora Brooks. I’m a cardiac ICU nurse, and I was buying paper plates for my daughter’s birthday when the man in the frayed field jacket folded like someone had cut the strings holding him up.

He was older, late seventies, hair gone silver under a ball cap, chest heaving like a trapped bird. A metal bracelet flashed on his wrist when his hand jerked—one of those medical alerts that only help if someone bothers to read them.

“Sir, you can’t block the aisle,” the manager said, voice tight with worry about a crowd more than a person. He crouched, but not close enough to see. “Sir, you need to step outside if you’re feeling unwell.”

“He can’t step anywhere,” I said, kneeling. “I’m a nurse. Call 911 now.”

I saw the bracelet. I saw the tiny etched words that matter when seconds do: heart condition, nitroglycerin inside left chest pocket. His lips were going grey-blue. He tried to speak and only managed a thin sound like paper tearing.

Two security guards arrived with uncertain faces and walkie-talkies buzzing. A couple of shoppers filmed at a polite distance, as if this were a show. The manager swallowed, glancing at the phones, at the crowd, at me kneeling on his floor.

“We’ll accompany you outside,” he said, soft but firm, and before I could stop them they hooked under the old man’s arms. “Ma’am, we have liability protocols, I can’t—”

“Read the bracelet,” I snapped. “Left chest pocket. There’s medication. Please.”

The medical part of my brain went automatic: airway, breathing, pulse. His breaths were shallow, pulse thready, sweat beading along his hairline although the store was cold. I could feel heat bleeding in from outside, 97 degrees waiting just beyond the sliding doors.

They got him into the sun.

He flinched like the light hurt. I did what I could with what I had—two shopping bags as improvised shade, my body between him and the glare. “Does this store have an AED?” I asked, already scanning walls for the little red case I have dreamed about in too many night shifts.

Before anyone answered, a rumble of old trucks pulled in, flags tied down, boxes stacked in the back. Not bikers, not a spectacle. A line of men and women in faded service caps and plain clothes—cựu binh—stepping out the way you learn to when your body remembers drills more than birthdays.

“We’re from Honor Watch,” the man in front said, already reading the bracelet as if he’d written it. “I’m Mack. Who called 911?”

“I did,” one of the guards muttered, shaken now that his radio had a real job. “They’re six minutes out.”

“Six minutes can be heaven or never,” Mack said. He slipped two gloved fingers into the jacket pocket, found the small brown bottle, and placed a tablet under the man’s tongue with gentle, practiced hands. “Ma’am, you’re the nurse. You run it. We’re your hands.”

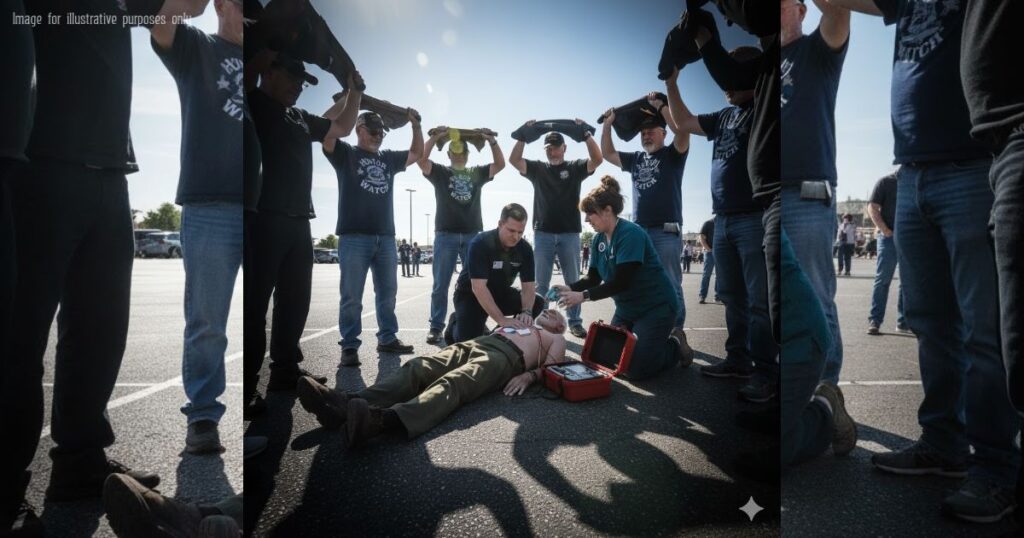

We built a circle.

Someone held a jacket for shade. Someone else knelt at the head and counted breaths with me. Another set a bottle of water near but not too near. Mack sent a younger vet sprinting inside for the AED they kept by the customer service desk the way some places keep hope.

The manager hovered, jaw working, eyes telegraphing a thousand second guesses. “I thought he was—” he started, and stopped. The sentence trailed off like a guilty person fleeing its own echo.

“Not that,” I said, watching the man’s chest. “He’s having a cardiac event.”

The AED arrived, red case snapping open, pads sliding free like we’d done this a hundred times. We exposed his chest enough to place them where they’d talk to his heart. The machine spoke in its crisp, mechanic voice that never shakes.

“Analyzing rhythm. Do not touch the patient.”

My hands lifted. The circle held still. A child nearby stopped crying because the adults had gone quiet in a way that makes even children listen.

“Shock advised.”

I pressed the button. The man jolted like someone had tugged his cord from the wall and plugged him back into the room. We went right back to compressions because electricity is only a door; you still have to carry someone through.

“One and two and three,” Mack counted, his palms over mine when I tired, then mine over his, trading without losing the beat. “Breathe,” I said, and someone with a pocket mask gave a careful breath, then another, the way you learn in a community class you never imagined would matter to anyone you love.

“Where’s the ambulance?” a woman asked, voice breaking. “Please.”

“Three minutes,” a guard said, and he had tears on his face, because sometimes the right thing arrives slower than your fear.

We changed out again. We watched for color. We ignored the cameras and the curious and the heat pressing hard against the backs of our necks. It felt like the whole day had come down to a metronome and the space between one word and the next.

“Come on, sir,” I whispered. “I need you here. Someone needs you here.”

His eyelids fluttered. Not much, a moth against glass. Then a cough that was mostly air but still a sound, and everyone exhaled the way you do when you’ve been holding your breath for the length of a prayer.

“Rhythm detected,” the AED said. It has no joy and no grief. We supply those ourselves.

The ambulance turned in with a sigh of brakes that sounded like rescue. The paramedics did what paramedics do: fast, clean, focused. We gave them what we knew, and they gave him oxygen, monitored him, lifted him, moved.

I leaned close to his ear as they loaded him. “You’re going to the hospital, okay? You’re not alone.”

His fingers found mine, papery strong. His lips formed words around the oxygen.

“Tell Ethan… I forgive him.”

The doors slid shut. I stared at the manager’s badge because suddenly I needed to read. The plastic tag caught the sun and gave it back: Ethan Cole. My stomach went cold, my heart too loud, and a dozen questions slammed into one word I couldn’t say yet—why.

Part 2 – The Seventeen-Second Clip

By the time the ambulance turned left onto the main road, the parking lot had become a rumor factory with cameras. A seventeen-second clip hit local feeds before I reached my car, trimmed to show a shaky shot of an old man on the ground and a caption that said, “Drunk transient causing disturbance.”

Security took my name and number with hands that still shook. Ethan stood a few feet away, ashen and wordless, watching taillights vanish like a verdict he couldn’t read yet. I wanted to say something measured and useful and landed on nothing at all.

At the hospital I couldn’t break rules just because my heart wanted to. I left a card with the charge nurse and a note for the attending: witnessed cardiac event, nitro administered, ROSC before transport, please call if family needs a translator. Someone in scrubs murmured that the cath team was on standby, which was both reassuring and terrifying.

Outside, the heat pressed against the windows like a heavy hand. I sat in my car and stared at my phone cycling through notifications that felt like a second siren. The clip bounced from one neighborhood page to another, collecting judgments the way asphalt collects heat.

I wrote what I could without violating anyone’s privacy. Three signs of a cardiac emergency, when to call 911, why nitrates matter, where to find an AED in most stores, what “analyze” and “shock advised” actually mean. I ended with a line I’ve repeated to every class I’ve ever taught: don’t guess a story when a life is unraveling, ask.

An hour later, a message pinged from a name I didn’t recognize until I did. “Nora, this is Mack from Honor Watch. Thank you for not letting him be a headline.” He asked if I could meet at their drop site behind a church gym because they wanted to coordinate next steps before the internet turned everyone into a jury.

They had built a neat city out of cardboard and care. Volunteers sorted canned beans and diapers while a radio hummed a station that belonged to nobody under fifty. Mack handed me a cheap spiral notebook and said, “Timestamps. Call log. Nothing fancy, but if people want receipts, we have them.”

The pages were orderly. Initial collapse, store call to 911, my intervention, AED retrieved, ROSC, ambulance arrival. He also showed me a dog-eared binder labeled Emergency Action Plans, the edges softened by use, not display. “We teach this stuff on Saturdays,” he said. “You’d be surprised how many folks show up because they lost someone in a lobby.”

I told him about the clip and the captions that erased everything that mattered. He nodded with the resignation of someone who has been edited by strangers before. “We can’t fight the internet,” he said, “but we can flood it with better stories and better trainings.”

“What about the store?” I asked. “They’ll circle the wagons.”

“We’re not interested in boycotts,” he said. “We’re interested in AED awareness, CPR sign-ups, and de-escalation training. If accountability looks like suspension and education instead of a public stoning, I can live with that.”

It sounded unglamorous and exactly right. I thought of the manager’s eyes when the AED spoke, the way his certainty split open and confusion fell out. I also thought of the oxygen mask and the quiet words in the ambulance: Tell Ethan I forgive him.

I went back to the hospital when the afternoon cooled by a single degree. HIPAA is not a decoration to me; it is a promise. The clerk could only say the patient was stable enough for visitors at the nurse’s discretion, which is hospital for “we see you, and we’ll do what’s right.”

Red’s room was quiet in the monitored way. The soft beep of an arterial line, the rise and fall of a chest that had argued with death and kept talking. His field jacket sat folded on the chair like a person who had stepped out to wash their hands and forgot to return.

I asked the bedside nurse if I could inventory his belongings for safekeeping, and she nodded the way nurses do when they’ve triaged your soul and find it not dangerous. There was a wallet, a worn photograph of a boy on a fishing dock, a battered pocket Bible, and an envelope tucked under the flap of the inner pocket like a secret hoping to be found. On the envelope he had written in block letters, “If I collapse, don’t guess. Ask.”

Red’s eyelids fluttered when I held the envelope up. I introduced myself again and told him I wasn’t family, only a witness with busy hands and a careful voice. He nodded once, the smallest yes in the world, and I eased the paper open like it might break.

The letter inside was half practical, half prayer. He listed his medications, his allergies, the location of the nitro, and then a line that made my throat hurt: “If Ethan is there, tell him I see him, not the years between us.” Two more sentences followed, about a fight in a kitchen on a winter night and a door that stayed closed too long.

I put the letter back exactly where it had been. I am not a judge, I am a courier, and the message belonged to both of them. When I stepped into the hall, the social worker was already walking toward me with a pad and the gentle caution of someone who knocks before every sentence.

“Are you the nurse from the store?” she asked, and when I said yes, she exhaled. “Good. The family contact is complicated, but the patient listed a number that belongs to a young man who answered and hung up the first time. He called back and said he’d come tonight.”

My phone buzzed at that exact unkind moment. The caller ID said Unknown, which is modern for “you will hate this or love it and you don’t know which.” I stepped into the family lounge and answered.

“Ms. Brooks?” The voice was young in the way tired can be young. “It’s Ethan. Security gave me your number. I know it’s a boundary to call, but I didn’t know who else to ask.”

I told him the only things I was allowed to say and the things I am allowed to be. He said he was sitting in his car in the hospital lot because he couldn’t make his feet go where his guilt had to. He also said a sentence I have replayed in my head since I learned to listen for the part of a story that is really a plea.

“I didn’t see him,” he whispered. “I saw a headline.”

We met in the cafeteria that smelled like coffee and clean floors. He held his cup with both hands as if heat could fix the cold he’d been living in. He kept glancing at the door as if expecting a uniformed mistake to walk through and write tickets on his shame.

“What did he say in the ambulance?” he asked. “They told me he spoke.”

“He did,” I said, keeping it simple because truth doesn’t need confetti. “He said to tell you he forgives you.”

Ethan closed his eyes like someone had turned down a dimmer in his chest. He told me about a winter five years ago, about a mother crying into dishwater and a boy who had decided anger was safer than grief. He told me he had a different last name because his father left early, and that he had avoided the old man in the field jacket in the cereal aisle for months because keeping your distance is easier than saying hello to a regret wearing boots.

I told him about the letter without reading it to him. He pressed the heel of his hand into his eyes and nodded like a person who has been waiting for a map and just got a compass instead. Then he said the first useful plan of the evening.

“If I go upstairs, I’ll say the wrong thing,” he said. “What if, tomorrow, I come to the community center instead? Mack left a message. He said they run classes. I want to sit in the front row and learn everything I should have known two days ago.”

We set a time because grief needs schedules to keep it from eating the whole day. I texted Mack and asked him to open one of their Saturday sessions early, just for a small, humbled audience. He answered with a thumbs-up and the words, “We have coffee, we have manikins, we have room.”

On my way out, I stopped by Red’s room one more time and rested my palm on the cool metal of the bed rail. I told him the truth the way you do with people who are sleeping under necessary drugs. His grandson was downstairs. He wanted to learn. He wanted to be the kind of man who counted compressions out loud even when nobody was filming.

Back in the lot, the air felt ten degrees softer than it had hours before, even though the weather app would disagree. Ethan stood by his car and looked up at the hospital windows the way pilgrims look at stained glass. He didn’t ask if Red would live because some questions are not for tonight.

“Tomorrow,” he said, like a vow more than a calendar entry. “I’ll be there before the doors open.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it twice. “Bring your hands, and bring your listening.”

He nodded, climbed into his car, and sat with the engine off until the night decided it could hold him. I drove home, set out paper plates on the counter for a birthday I refused to cancel, and wrote three words on a sticky note for the morning.

Don’t guess. Ask.

Part 3 – Investigation and the Plan

By Saturday morning the air had cooled a single stubborn degree. The community center doors were propped with orange cones, and a hand-lettered sign read, “CPR/AED Training—All Welcome—No Filming.” Inside smelled like coffee, floor wax, and hope.

Mack was already there with three manikins, two AED trainers, and a stack of laminated cards that said, “Check. Call. Compress. Shock. Continue.” He greeted me like a colleague, then poured coffee into a paper cup the color of compromise.

Ethan arrived before the hour and hovered by the threshold. He wore a plain shirt and the kind of face you get when the night has opinions. He lifted a hand in an awkward wave and didn’t trust it to do more.

“We start with the chain of survival,” I said, clapping to gather the handful of early arrivals. “Recognition, emergency response, high-quality CPR, defibrillation, and post–cardiac arrest care. You don’t need a cape. You need a plan.”

Ethan took a seat in the front row like he’d promised. He set his phone screen-down on the floor and nudged it under his chair as if hiding a small animal. Mack nodded, pleased at the ritual.

We talked about bystander hesitation. People freeze because they’re afraid of doing the wrong thing or being recorded doing it imperfectly. I told them what I tell every class: your fear cannot keep blood moving, but your hands can.

We practiced compressions. Thirty counts out loud, two inches deep, chest recoil, minimal pauses. Ethan’s first set was shallow and too fast, the rhythm of a guilty heart, not a metronome. I put my hands over his and slowed him, counting with him until the room began to sound like a dozen steady clocks.

“Good,” Mack said. “Now trade. Nobody owns the hero job alone.”

We added the AED trainer. The plastic pads clicked into place. The machine said its careful lines with no interest in our feelings. A young cashier from the store asked if she could hurt someone by shocking them accidentally, and I told her the best truth in the room: the device will not deliver a shock if the rhythm doesn’t call for it.

Ethan raised his hand. “What about liability?” he asked. “We were always told not to… interfere.”

“Policies matter,” Mack said, voice even. “So does a pulse. There are community protections in many places for good-faith aid, but this is a training, not legal advice. The store can update protocols to encourage action that aligns with current guidelines.”

We took a break. Mack passed out peanut butter crackers and the laminated cards. Ethan stood near the water fountain, staring at the manikin like it contained the worst version of yesterday. He caught my eye and offered a brief, lopsided apology for nothing in particular.

“Tomorrow we’ll run a full drill,” I said. “No warnings. You’ll hate me for ten minutes and love me for the rest of your life.”

He tried to smile. It landed like a promise that wanted more practice.

By noon, the district manager from the store came quietly through the back door. She introduced herself as Ms. Alvarez and asked if we could meet after class. She carried a notebook and a posture that said both accountability and caution.

We sat at a folding table while volunteers reset the manikins for the afternoon group. Ms. Alvarez kept her voice low and neutral. “We’ve placed Ethan on paid administrative leave while we review the incident,” she said. “We’re interviewing witnesses, pulling the full footage, and reviewing our emergency procedures. We don’t comment publicly without context.”

“That’s fair,” I said. “People are angrier when they’re scared. They calm down when they see a plan.”

She asked whether Honor Watch could run on-site trainings for all shifts over the next month. Mack said yes before the sentence finished. We sketched a schedule, talked about de-escalation, and wrote a single non-negotiable on the whiteboard: no moving a distressed person outside unless there is immediate danger inside.

We walked the store together that afternoon. The AED cabinet was mounted behind a display that made it visible to almost nobody. The battery indicator blinked a tired warning. A manager fetched the key, and we tested the unit, then ordered fresh pads and a spare battery while the decision was warm.

“Make a map,” Mack told the assistant manager. “Put it at every register. AED here, exits here, oxygen at customer service if applicable, who calls 911, who meets EMS at the door. Nobody should be guessing when it’s loud.”

Ethan kept a respectful distance, hands clasped, saying little. Ms. Alvarez gave him tasks that were practical and not performative: reorder signage, mark the floor with a small decal pointing toward the AED, update the shift binder with the emergency plan. He did each one like a person studying for a test that mattered.

A rumor ricocheted through the community pages that afternoon: a longer clip existed showing volunteers and an AED. Someone posted a still frame of my back and Mack’s hands, the circle of people making shade that turned asphalt into a room. Comments pivoted from blame to confusion to something that sounded like learning with an accent of relief.

We ignored it as best we could. Internet weather changes every hour. What we could hold were the schedules and the printed sign-up sheets that filled from left to right in plain blue ink. People were putting their names under “CPR Sunday, 2 p.m.” as if signing up for choir.

In the evening I returned to the hospital. Red was awake, drowsy with the kind of careful medications that make pain a memory and time a soft-edged thing. He recognized me with a small tilt of his mouth that had more history in it than I deserved.

“We trained today,” I told him. “Your jacket’s famous. The note about not guessing? We made it a card.”

He coughed once and pointed at the bedside tray for a pen. His hand moved slow but certain. He wrote three words on the back of a nutrition label and slid it toward me.

“Teach him counting.”

I smiled at how specific and generous the instruction was. Counting gives your brain a job so your fear can’t keep it. I tucked the scrap into my pocket like a credential.

The social worker came in with a polite knock. She had a folder and a face that said she had navigated harder hallways than this. “Mr. Delaney,” she said, “we’re updating contacts. Do you want Ms. Brooks to be present when we call your grandson?”

Red nodded. The word “yes” was there even if he didn’t make it with his mouth. The social worker dialed the number from the chart while we stood very still, as if the line itself could spook.

Ethan answered on the second ring. He listened without interrupting. When she asked if he wanted to visit under staff guidance, he said he did, but that he’d like to attend one more training first. His voice had an extra hinge in it, something creaking open.

After the call, Red tapped the drawer, and the nurse handed me the field jacket folded like a flag. “Inner lining,” he whispered. “Left.”

The lining hid a second envelope stitched along the seam with clumsy, earnest thread. I eased it free and showed him the front. He closed his eyes briefly the way people do before a needle or a truth. On the paper were three words in the same block letters I had seen before: “For Ethan—Kitchen.”

“I won’t read it,” I said. “I’ll carry it.”

He exhaled, relieved, and drifted toward sleep. The monitor traced a better story than yesterday, green lines telling us what words could not.

On my way out, I stopped by the charge desk and left two notes. One was for any nurse who needed language for families that ask what to do during a cardiac emergency. The other was a time for tomorrow’s early session with the store team. I printed extra “Check. Call. Compress. Shock. Continue.” cards because nothing good ever came from running out of simple steps.

The parking lot felt different when I stepped into it. Not cooler, not louder. Just occupied by people doing small right things. A volunteer from Honor Watch was at the curb with a clipboard, taking names for meal deliveries. A teenager taped a flyer to a lamppost about Sunday training and asked me if he should make a Spanish version. I said yes and thanked him like he had invented light.

Ethan texted a few minutes later. “I’m re-reading tomorrow’s notes,” he wrote. “I keep tripping on step one.”

“What’s step one?” I asked.

“See the person.”

I told him that was step zero, the one you do before you know there’s a list. He sent back a single check mark and a picture of the laminated card pinned to his refrigerator with a magnet shaped like a red apple.

Before I turned the ignition, I took the envelope from my pocket and held it against the steering wheel. I didn’t open it. I thought about kitchens and winters and words said loud enough to leave frost. I thought about how forgiveness and instruction can be the same gift when you hand them to someone still learning how to hold them.

Tomorrow we would run the first full drill in the store before opening. Tomorrow Ethan would count to thirty with a voice that did not shake. Tomorrow, if Red was awake, we would bring him a video of hands moving in rhythm like a promise kept out loud.

For tonight, I drove home to frost a cake and tape a new card by my own door. It said what I wanted my daughter to know before she ever filmed a stranger on a floor.

Don’t guess. Ask.

Part 4 – Letters in the Lining

Sunday slid in quiet and bright, the kind of morning that makes even parking lots look almost kind. The hospital felt softer, too. Red had color in his cheeks that wasn’t just the monitors lying for our comfort.

He opened his eyes when I stepped in and found me without surprise. His hand was still a little tremor and a lot of stubborn. I set his field jacket on the chair and the sealed envelope on top like a small, careful lighthouse.

“I didn’t read it,” I said. “I’ll carry it wherever it needs to go.”

His mouth tugged into something like a thank-you that didn’t waste breath. He tapped the tray table. I slid the pen into his fingers and waited while he wrote, slow deliberate letters that looked like they had walked a long way to get here.

“Kitchen,” he wrote, and underlined it once. “Winter. Loud. Sorry.”

I pulled the chair closer. “You can tell me as much or as little as you want,” I said. “I’ll tell him only what you want me to.”

He held my eyes the way some people hold ropes. “Raised him wrong,” he whispered. “Raised my voice. Wanted him tough. Forgot to be kind.”

He blinked and a single tear slipped the way a person does when they’re done pretending. I pressed the call button for the nurse because we never do this alone, not even the quiet, voluntary hurts. The nurse adjusted his oxygen, nodded at me to go on as if the room itself were giving permission.

“He’s coming to training again,” I said. “He wants to sit in the front row.”

“Count,” Red said. He made his finger tap the rail in a rhythm I knew now by muscle more than mind. “Teach him counting.”

“I will,” I promised, and meant it like a vow you could hang a day on.

Mack came after lunch with a plastic bag of ordinary treasures. A Polaroid of a boy on a dock holding a fish too big for his grin, a faded receipt with a grocery list in Red’s block letters, a note card scrawled with “CPR Sat 10 a.m.—bring coffee.” He put the photo on the tray, and Red’s hand drifted to it like a homing pigeon.

“Honor Watch can set up a bedside drill,” Mack said softly. “When he’s ready. No pressure. Just hands and hopes.”

“Tomorrow,” Red murmured, and the nurse shook her head, then gave up and smiled the way nurses do when a patient decides on a small future.

I left before visiting hours ended because there were other promises keeping time. The community center had volunteers moving tables, taping arrows to the floor, stacking a pyramid of paper cups with the care people reserve for fragile things. The whiteboard read, “CPR/AED—Spanish session 3 p.m.—Childcare in Room B.” I stood there and breathed like a person who had borrowed a little hope and returned it with interest.

Ethan was already in the corner with a manikin, practicing the way anxiety practices—too fast, too shallow, too afraid of being seen doing it wrong. I knelt beside him and held my hand above his to set the pace without catching his pride.

“Chest back up between compressions,” I said. “Full recoil. That lets the heart refill. Press, rise, press. Let your palms do the talking.”

He adjusted and the sound changed. The plastic clicked in a way you learn to love. He looked at me as if I’d handed him a language he could actually pronounce.

“I have the envelope,” I said. “He wants you to open it somewhere that makes sense. He underlined ‘kitchen’ like it was a map.”

Ethan closed his eyes and exhaled long enough to empty a room. “Five winters ago,” he said. “He came over after my mom’s late shift. It was cold and everything sounded like it was made of glass. I told him I didn’t want to talk about my dad. He told me being a man meant not making excuses. I told him being a man meant not leaving. We were both wrong and both sure.”

I didn’t reach for him. I waited the way you wait for a pulse after a shock. He opened his eyes with the stubbornness of someone who wanted to do a hard thing correctly.

“I’ll read it tonight,” he said. “In a kitchen. Not mine. The center’s has a wobbly table and a jar of mismatched forks. It looks like forgiveness could live there.”

“Good,” I said. “Bring a pen. Letters need answers.”

Ms. Alvarez arrived in the afternoon with a man from facilities and three employees from different shifts. She didn’t bring a camera. She brought a clipboard and an apology that didn’t bother with spectacle.

“We’re rewriting the emergency protocol,” she said. “No moving symptomatic customers outside unless there is fire, smoke, or an immediate hazard inside. Supervisors will carry one-page checklists. We’ll run nocturnal drills for the overnight crew.”

Mack spread the store layout across a table and turned into a general in jeans. “AED here, not hidden behind promotional towers. Radio channel three is medical. One person calls 911. One greets EMS at the door. One clears a radius. Everyone else protects privacy and fetches supplies.”

We walked the physical space again at dusk. The AED cabinet moved to a column by the entrance with a decal so obvious you couldn’t look away from it. A small sign under it read, “If you wonder whether to use this—yes.” The assistant manager labeled a drawer “Pocket Masks—Gloves—Scissors” and placed it directly below.

Ethan found me in Aisle Four with a stack of laminated cards. “Can we put these at every register?” he asked. “Not the big poster. Just this. People read small things while they wait.”

We did it together. The last card was slightly crooked, and he adjusted it twice until it decided to cooperate. It felt like fixing a picture frame in a house you planned to keep.

Evening came with a breath that didn’t feel like heat for the first time in days. The community center kitchen smelled like clean metal and old coffee. Ethan set the envelope on the table and waited before touching it, as if something sacred needed a minute to sit down.

“Do you want me to stay?” I asked. “I can stand outside and keep time.”

He shook his head. “I should hear him by myself first,” he said. “Then I’ll call you. If I try to do this alone-alone, I’ll make a religion out of the wrong details.”

I left him in the doorway with the letter and the light. I stood in the hall counting my own breaths because sometimes you have to practice what you preach in the quiet where nobody claps.

The call came twenty minutes later. He didn’t start with hello.

“He remembered the nickel,” Ethan said. His voice was soft, almost smiling. “When I was ten I taped a nickel under my mom’s kitchen table because I’d read it was good luck. He wrote, ‘Check under the table when you can stand to. Luck only helps the people who show up.’”

“Did you check?” I asked.

“Community center tables are plastic,” he said. “I checked anyway.”

We both laughed the kind of small laugh you have to earn. Then he told me the rest in fragments that felt like stitches. Red wrote about the winter fight. He wrote about losing his own son to distance long before he lost him to anything final. He wrote how grief turns some people stone and some people water and how he had chosen stone because it didn’t run, forgetting it also doesn’t hug.

“He wrote, ‘I taught strangers to keep a pulse but not my boy to keep a conversation,’” Ethan said, and I could hear the letter folding and unfolding as if it were making its own apologies. “He asked me to learn counting so we could count together. Stories, breaths, minutes. He said the kitchen was where we forgot how to be gentle, so it should be where we start again.”

“Then start,” I said. “Starting is loud and clumsy. That means you’re doing it.”

He cleared his throat. “Can you… will you be there tomorrow when I go upstairs? I want to say it with a witness so I don’t run.”

“I’ll be there,” I said. “We’ll keep time if words run out.”

Before we hung up, he asked a practical question that made me like him even more. “When I counted compressions today, I kept losing track at fifteen,” he said. “What do you do when your brain squirrels off?”

“Say the numbers louder than your fear,” I said. “Tie them to something that matters. I tie one through ten to my daughter’s birthday month and start over. Your brain loves anchors.”

“That’s good,” he said, and you could hear the note go into a pocket where it would survive a fall.

I walked back to the kitchen and found the envelope flattened on the table, an empty boat that had safely crossed. Ethan stood by the sink rinsing his face with the kind of water that probably wasn’t necessary and exactly was.

“Tomorrow,” he said when he saw me. “We do the drill at dawn, then the hospital. I won’t be late.”

“You’ll be early,” I said. “That’s how you are now.”

He looked down at his hands as if meeting them for the first time. “They feel different,” he said. “Like they learned a word.”

“They did,” I said. “It’s ‘stay.’”

That night, before bed, I wrote a note on my own refrigerator magnet. Not for my daughter this time, not for the internet. For me. It said, “When in doubt, count out loud,” and underneath, “When in doubt, listen even louder.”

Morning would bring fluorescent lights and a closed store and a clock that takes its job seriously. It would bring a circle of people who had decided to be more useful than noisy. It would bring a grandson walking into a room where a monitor would insist on its quiet song and an old man would try very hard to be softer than his memories.

We would bring our hands. We would bring our counting. And if we ran out of the right words, we would choose the right actions until words remembered how to behave.