Part 1 – The Monster Is Finally Gone

On the same day a decorated veteran died alone in a cheap roadside motel, his famous therapist son went viral for writing, “The monster who raised me is finally gone,” and the internet called it healing.

My name is Elena Cruz, and I am the person the county calls when no one wants to claim the body. I process unclaimed veterans, fill out forms, contact next of kin, and try not to think too hard about who they used to be. Most days, it feels like paperwork with dog tags attached.

That morning, I was on my lunch break scrolling my phone when the post hit my feed. A clip from a podcast, a quote card, a handsome man in a pressed shirt saying, “When he died last night, I finally slept without checking the door.” The caption underneath read, “The man who terrorized my childhood is gone. Today I am free.”

Comments poured in faster than I could read them. “So proud of you for cutting off toxic family.” “You owe abusers nothing.” “This is what healing looks like.” The username at the top of the post was one I recognized from billboards and book covers around town: Dr. Mark Harlan.

I locked my phone and went back to my desk. There was a new file in my in-box, a manila folder with a red stamp that always makes my stomach sink: UNCLAIMED VETERAN. I flipped it open, half on auto-pilot, expecting the usual: age, branch, cause of death, last address, next-of-kin information that goes unanswered.

The name on the first line stopped me.

HARLAN, DANIEL R.

Date of birth, service record, discharge papers, a stack of medical notes. And at the bottom, in messy handwriting from the hospital: “Son: Dr. Mark Harlan. No contact. Refused notification.”

I stared at the page so long my vision blurred. Somewhere in the city, Mark Harlan was being applauded for surviving “the monster who raised him.” In my hands, I held the file of that so-called monster, tagged for disposal like he was nobody’s anything.

Protocol said I had to call anyway. I dialed the number listed under “next of kin” and listened to it ring. When the voicemail picked up, it was the same voice from the viral clip, smooth and calm, inviting callers to book sessions online. I hung up and tried the emergency number beneath it. This time, he answered.

“This is Dr. Harlan.”

“Dr. Harlan, my name is Elena Cruz. I’m calling from the county veterans’ service office about your father, Daniel—”

“He’s dead,” he cut in. “Yes, I know. I got the email from the hospital.”

“Yes, sir. As next of kin, you have the right to decide his arrangements. We can help coordinate a service, a flag detail, or—”

“No service,” he said, the words clipped and cold. “No flag, no obituary, no anything. Cheapest cremation you offer. Just send me the bill.”

I hesitated. “Sometimes other family members, or people from his unit, like to—”

“There is no family,” he said. “Not in the way that matters. He chose the bottle and his anger over all of us. My clients watch me every day to see if I keep my boundaries. So this is me keeping them. Do you understand?”

“I understand your position,” I said quietly. “I do need your signature on the authorization.”

He sighed, impatient. “Email it. I’ll sign. But I am not showing up to pretend he was anything other than what he was.”

The line went dead.

For a long moment I just sat there, receiver still in my hand, listening to the empty buzz. I have seen children pay for flowers they could not afford and I have seen families vanish when it was time to choose a casket, but I had never heard anyone sound relieved that a parent was gone.

I went back to the file. The farther I read, the stranger it felt. Daniel had multiple notes from a local clinic calling him a “peer support volunteer.” There were printouts from a community center listing him as “Doc Harlan – veterans’ group.” His chart mentioned “fifteen years sober,” though there were older entries that told a different story.

That afternoon I drove to the motel where he had died. It was the kind of place no one books on purpose, with a flickering sign and curtains that never fully close. The manager met me at the door with a plastic bag of toiletries and a key card, muttering something about “quiet old guy, always paid cash, never caused trouble.”

Inside, the room was cleaner than I expected. The bed was made, the trash empty, a Bible open on the nightstand with a worn card tucked inside from a support hotline. The air smelled faintly of antiseptic and cheap coffee. There were no family photos, no framed certificates, nothing that told you who this man had been.

I gathered the few belongings the county allowed us to store: a duffel bag with neatly folded clothes, a pair of boots polished within an inch of their life, a tin box with a tiny combination lock. The bottoms of my shoes stuck slightly to the old carpet as I lifted it onto the bed.

The combination was written on a Post-it stuck to the lid, the way older vets do when they stop trusting their memory. My chest tightened as I peeled it back and spun the dial. Inside, there was no cash, no weapons, nothing dramatic. Just a folded letter, a small metal key taped to the corner, and a dog tag on a chain that was not his.

The letter was addressed to “Whoever has to clean up my mess.” The handwriting was shaky but steady enough. I unfolded it carefully.

“If you are reading this, it means my body got where it needed to go. Thank you for that. I know I did not earn anyone coming to claim me. But there are some men and women who will wonder why I disappeared, and they deserve better than that. The key is to Unit 37 at Northside Storage. Please make sure my guys know I didn’t just walk away.”

I read it twice, then a third time. “My guys.” We use that phrase a lot in this line of work, but usually it is staff talking about clients. I had never seen it from a man who died alone in a motel, tagged as unclaimed.

Technically, my job ended at logging his possessions and arranging transport. The storage unit was not county business. It was a piece of a life I had no right to open. I told myself that as I drove out of the motel lot with the key burning a hole in my pocket. I told myself again as the sun dipped low over the strip malls and billboards.

By the time I turned into Northside Storage, the sky had turned the color of old bruises. The manager was locking up, but he recognized my county badge and let me in with a shrug. Row after row of metal doors stretched out under humming lights, each one hiding someone’s private history, someone’s almost-forgotten self.

Unit 37 was near the back, away from the main gate. I stood in front of it longer than I needed to, the cool metal of the key sweating in my palm. Somewhere on my phone, strangers were still applauding a son for finally feeling safe now that his father was gone. Somewhere in a county cooler, that father lay on a steel tray with a tag on his toe.

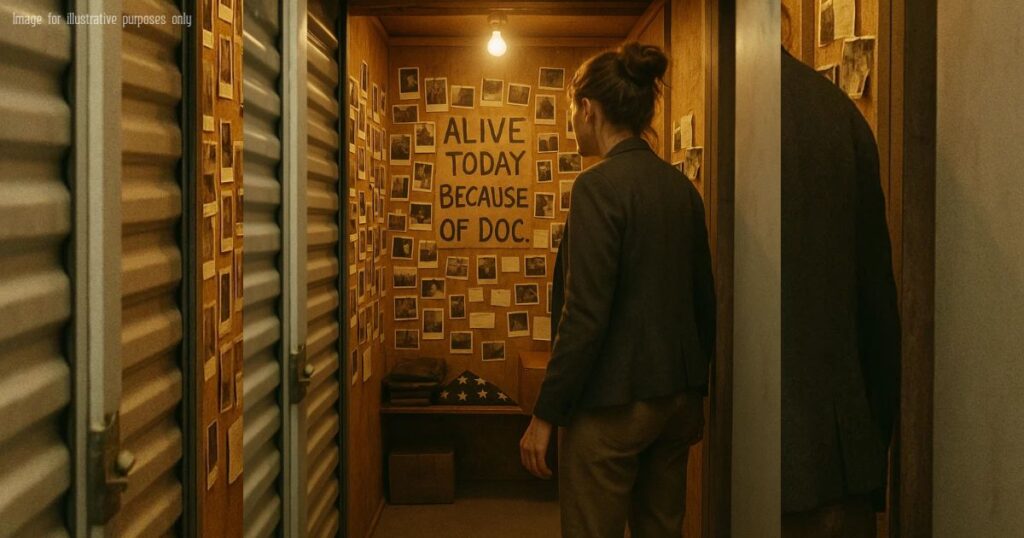

I slid the key into the lock and turned. The padlock clicked open with a sound that felt louder than it should have. I pulled the metal door up; it rattled on its track and the smell of dust and cardboard rolled out in a dry wave. A single bare bulb hung from the ceiling, dark and waiting.

I stepped inside and pulled the chain. Light flickered, steadied, and the room came into focus.

What I saw on the back wall made my breath catch in my throat. It was not a hoarder’s chaos or a drunk’s mess. It was an altar of faces and folded flags and hand-written words that all said the same thing in different ways:

“ALIVE TODAY BECAUSE OF DOC.”

In that instant I realized the man the internet had labeled a monster had been spending his last fifteen years building a secret world out of other people’s second chances. And I had just opened the door to it.

Part 2 – The Wall of the Lives He Saved

The wall was a collage of lives that had almost ended.

Photos were taped in uneven rows, edges curling from heat and time. Some were printed on cheap drugstore paper, others were instant shots with cloudy colors. Underneath each face, in thick black marker, Daniel had written a date and a simple phrase. “Six months clean.” “First apartment.” “Met my son again.”

Under the biggest cluster of photos, he had taped a strip of cardboard. The letters were clumsy, like he had cut them from a cereal box and traced them.

ALIVE TODAY BECAUSE OF DOC.

I stepped closer without realizing it, drawn like I always am to proof that someone mattered. The metal floor creaked under my shoes. My fingers hovered over a picture of a young woman in a wrinkled T-shirt, holding a baby whose fist was wrapped around her dog tag. Underneath, Daniel had written, “No more sleeping in the truck. Welcome home.”

Around the walls sat boxes, neatly stacked and labeled by year in black marker. 2008. 2009. 2010. The handwriting grew more steady as the years went on, like his hands had stopped shaking. On the top of the closest box, he had written two words that did something strange to my chest. “Year One.”

I slit the tape with my county-issued pocket knife and lifted the lid. Inside were folders, old coffee-stained notebooks, a handful of meeting flyers from a community center that simply said “Veterans’ Night – Come as you are.” Tucked into the front was a small spiral notebook with the date on the cover and the word “Try Again” underlined twice.

I opened it to the first page.

“Day 1 without a drink. Don’t know if I can do it. Don’t know if I even deserve to. My boy won’t talk to me. He’s right not to. I see his face every time I close my eyes. Signed up to sit in on a group at the clinic instead of sitting at the bar. If I can’t be a father to my own son, maybe I can keep somebody else’s alive.”

The next pages were a mix of observations and confessions. Notes about men who flinched at door slams. Women who woke up in the night hearing helicopters only they could hear. People who sat in their cars outside the clinic and never walked in.

Over and over, he wrote the same reminder to himself. “Listen more than you talk.” “Don’t pretend you know their exact war.” “Call them tomorrow.”

At the back of the notebook was a list of first names and phone numbers. Some had a single check mark next to them. Others had lines of dates, notes like “answered,” “left a message,” or “sat with him in the parking lot.” Next to one name he had written, “Picked up on the third ring. Still here.”

I put the notebook back in the box like it might break. My job trained me to stay detached, to file, to sign, to let go. But there in that metal unit, surrounded by years of effort no one had asked him to make, detachment felt like an excuse.

I moved through the boxes slowly, as if I were walking through a church. Each year had the same pattern. Meeting notes. Flyers. Names and numbers. Letters. So many letters.

Most were thank-you notes from people who had clearly never meant to be poetic. “Thank you for showing up when I wouldn’t answer anyone else.” “Thank you for sitting in silence and not leaving.” “Thank you for reminding me I am not only what happened over there.”

Some letters were folded inside envelopes with no stamps, addressed but never mailed. “Mark.” “Son.” “My boy.” The writing on those was different, tighter, like he had been squeezing the pen too hard.

I told myself I wouldn’t read those. That there were lines I shouldn’t cross. I lasted about thirty seconds.

The first one began, “I understand why you don’t pick up.” That was as far as I got before my throat closed. I put it back. Those belonged to a conversation that would never happen, not to me.

It was easier to look at the photos. In one, Daniel stood in a folding chair circle, hands on the shoulders of two men about his age. They all had that same tired, wary look I knew too well from waiting rooms and hospital corridors. In another, he was at a picnic table, grill smoke behind him, a group of younger faces crowding in, holding up soda cans in a mock toast.

There were no pictures of him with children. No birthday parties, no school plays. The absence of those stood out like a shadow.

On a small metal filing cabinet pushed against the side wall, I found a three-ring binder with “Wednesday Night Group” written on the front. Inside was a carefully typed list of emergency contacts, arranged not by last name but by who checked on whom. Arrows connected people, forming a rough web. At the top, Daniel had written, “If I go first, don’t let anybody fall through.”

A chill slid down my spine. I thought of his body in the morgue, tagged and waiting. I thought of this web of people who only knew him as “Doc,” who would show up to a meeting next week and not know why the chair in the corner was empty.

Technically, no one required me to tell them. It wasn’t in the checklist. The county cared about signatures and storage time limits, not about whether the group in a community center basement had closure.

But the letter in the tin box had been clear. “Please make sure my guys know I didn’t just walk away.”

I sat cross-legged on the concrete floor, binder open on my lap, and scrolled through my phone for the number to the small clinic listed on the flyers. The receptionist recognized my name and position. When I asked about their peer support group, she sighed.

“You mean Doc’s group?” she said. “He hasn’t been in a few days. We figured he was just worn out.”

“He passed away,” I said softly. “I’m handling his file.”

There was a long pause, and then a shaky, “Oh.”

I explained about the storage unit in broad strokes, trying not to violate more privacy than I already had. “He left notes asking that the people he supported hear it from someone, not from an empty chair.”

“We have a meeting tonight,” she said. “Would you come tell them?”

Every part of my training said no. I was supposed to stay behind the scenes, invisible, a name at the bottom of forms. But I thought of the photos on the wall and the words on that piece of cardboard. Alive today because of Doc.

“Yes,” I heard myself say. “I’ll be there.”

After I hung up, I stared at the web of names in the binder and did something I had never done before. I started dialing the numbers on the “call if absent” list.

The first one went to voicemail. The second rang and rang. The third connected.

“Hello?” The voice on the other end sounded wary, like he still braced for bad news after all these years home.

“Hi, my name is Elena,” I said. “I work with the county veterans’ office. I’m calling about someone you probably know as Doc.”

There was a sharp intake of breath. “Is he okay?”

I swallowed. I had to get the words right. “He died two days ago,” I said. “He left a note asking that the people in his group hear it from someone who knew what he meant to them.”

For a moment, there was only silence. Then, quietly, “No. No, he was just here last week. He said he’d be back. He always comes back.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m so sorry.”

The man on the line cleared his throat, voice rough. “He sat in my driveway for three hours once,” he said abruptly. “Just so I wouldn’t go back to the bar. I told him to leave and he said, ‘I’ll go when you believe you’re worth more than that.’ Do you understand what I mean?”

“Yes,” I said. And I did.

“You said there’s a meeting tonight?” he asked.

“There is,” I replied. “They asked me to come and tell everyone officially. I thought you might want to be there.”

“I’m bringing my whole family,” he said. “My kids call him Uncle Doc. They need to say goodbye too.”

After we hung up, I realized my hands were shaking. Not from fear exactly, but from the weight of what I had just set in motion. It felt like pulling on a thread that ran through dozens of lives, lives that had been quietly rewoven by a man his own son had turned into a warning story.

I closed the binder and looked around the unit one more time. On a low shelf near the door, partially hidden behind a stack of folded blankets, something caught my eye. A small box with a strip of duct tape on the top. On it, in slightly neater handwriting than the others, were three words.

“For Mark and Lily.”

I sat back on my heels. Until that moment, Mark’s daughter had been an abstract name in the file, a “grandchild: unknown contact” note in a system that wasn’t built for nuance. Seeing her name in Daniel’s hand made her suddenly, painfully real.

My phone buzzed with a new notification. A friend had sent me the viral clip of Dr. Harlan again, this time from a national account, captioned, “Proof you can heal without ever forgiving the person who hurt you.” Views were climbing by the second.

In a cold, humming storage unit on the edge of town, I was holding a box that might complicate that story more than anyone was ready for.

I slid “For Mark and Lily” carefully into my bag, turned off the light, and pulled the roll-up door down until it clanged shut.

Outside, the evening air felt sharper, like the world had been peeled back a layer. Somewhere in a studio, cameras were pointed at a man telling a one-sided truth that had kept him alive. Somewhere under a sheet, another man lay still, surrounded by the evidence of how hard he had tried to become someone different.

And somehow, between my badge, my conscience, and the box in my bag, I had just stepped into the space between them.

Part 3 – The Therapist Son Who Built a Life on Leaving

The community clinic sat in the middle of a strip mall between a nail salon and a tax prep office. At six thirty that evening, every parking space in front of it was taken. I had to park two rows back and walk past a line of trucks and older sedans that all looked like they had seen more miles than their owners wanted to talk about.

Inside, the waiting room smelled like burnt coffee and disinfectant. A handwritten sign taped to a door read “Wednesday Night Veterans’ Group – Conference Room B.” I could hear low voices on the other side, the kind of murmur you hear at church before a service starts, when no one quite knows what to say yet.

The receptionist nodded when she saw me. “They’re ready,” she said quietly. “They know he’s gone, but not how, not officially. They were hoping you could… fill in some of the blanks.”

Conference Room B was too small for the number of people squeezed into it. Metal folding chairs ringed a long table, but more had been shoved against the wall and into the corners. Some of the faces were familiar from the photos in the storage unit. Others were strangers who somehow felt familiar anyway, with their tired eyes and stiff shoulders.

I introduced myself, explained my role, and told them what I knew. I said the words “Daniel Harlan” and watched their expressions change. Some flinched like it hit a bruise. Some let out a breath and murmured, “Doc.”

“He died at the motel two days ago,” I said, keeping my voice steady and clinical because that is the only way I know how to do this. “Natural causes. The hospital did what they were supposed to do. The county is taking responsibility for his remains.”

“What about a service?” a man near the back asked. His hair was close-cropped, his posture too straight for a civilian chair. His hands were clenched around a baseball cap.

I shook my head. “His son declined funeral services. He requested a simple, no-ceremony cremation.”

A low rumble moved through the room. It was not quite anger and not quite surprise, more like confirmation of something they had all suspected and hoped wasn’t true. A woman near the door, her hair shot through with gray, squeezed her eyes shut for a moment like she was holding back tears.

“He told us they wouldn’t come,” she said quietly. “But he always left a plate at the table anyway.”

I told them about the storage unit. Not everything, not the letters to his son, not the box with Mark and Lily’s names written on it, but enough. I described the wall of photos and the cardboard sign. I told them about the emergency contact web he had built.

The room went very still. A man with a scar running from his ear to his jaw cleared his throat. “That sounds like him,” he said. “Always making something out of nothing. I was nothing when I rolled into group. Just a guy who couldn’t sleep without a bottle. He sat with me three nights in a row in my truck. Didn’t say a word the first night. Just sat. Who does that?”

Several heads nodded. Stories started to spill out, stepping on each other, overlapping.

“He showed up at my house with groceries when the check got held up.”

“He went with me to my first doctor appointment because I thought if I walked in alone, I’d turn around.”

“He called me on Thanksgiving every year just to say, ‘You’re still here, right? Good.’”

“He told my kid I was brave for asking for help. Nobody had ever called me brave for that.”

I listened and took mental notes, each story another piece of a man whose official paperwork was so sterile it could have belonged to anyone. They talked about his bad jokes, his stubbornness, the way he refused to let anyone sit with their back to the door. They mentioned his temper too, but always in the past tense, like a ghost that had been acknowledged and then laid to rest.

“He never pretended he hadn’t messed up his own family,” the gray-haired woman said. “He just kept saying, ‘I can’t fix what I broke there, but maybe I can keep you from breaking yours.’ It made some of us mad at first. Then it made sense.”

When there was a lull, I cleared my throat. “He left very little money,” I said. “The county will cover the basics. But if you want anything more than that—anything that reflects who he was to you—that would have to come from outside funds.”

There was no hesitation. Chairs scraped as people stood, reaching for wallets and purses. One man pulled a folded envelope from his pocket.

“He’d kill us for doing this,” he said with a crooked smile. “Which is why we’re going to do it right.”

The room lightened a little. They started talking about renting space at the community center, about a potluck, about tapping into local veterans’ groups and motorcycle clubs without making it about politics or spectacle. They wanted a microphone, not for speeches, but for anyone who needed to say “thank you” out loud.

As they talked, my phone buzzed. A notification banner slid across the screen. “Dr. Mark Harlan to host live event: Healing from Harmful Parents. Tickets available now.” Beneath it, a thumbnail image of Mark’s face, professional and composed, with the tagline, “You don’t have to forgive to be free.”

I tucked the phone away. I had no business at that event. I was a county employee, not an activist, not a journalist, not a friend. I was already teetering on the edge of lines I was supposed to stay behind.

But when the meeting ended and people drifted out in small clusters, someone tapped my arm. It was the gray-haired woman. Up close, I could see the fine lines around her mouth that come from years of biting back words.

“You said his son declined a service,” she said. “Does that mean his son doesn’t want to hear any of this?”

I chose my answer carefully. “I don’t know what he does or doesn’t want to hear,” I said. “I know he has his reasons.”

She nodded slowly. “We all do,” she said. “That’s the problem and the blessing. Just… if you ever talk to him, tell him this. Doc never told us to forgive our families. He just begged us not to become them.”

On the drive home, the clinic’s stories and the storage unit overlapped in my mind like transparent slides. The phrase on the cardboard, the phrase on Mark’s event advertisement, the phrase that seemed to sit between them: You don’t have to forgive. You don’t have to stay the same either.

The event ad followed me. It showed up when I checked my email, when I opened a news app, when I tried to distract myself by scrolling through a recipe site. “Limited seats remaining,” the banner said, as if this were a concert instead of a man’s pain packaged for an audience.

Two days later, I found myself standing in line outside a renovated theater downtown, clutching my ticket like an apology. The crowd was younger than I expected, a mix of professionals in neat casual clothes, people with notebooks, couples holding hands like they had come to fix something together.

No one there knew that while they had been refreshing a ticket page, I had been standing over a steel tray in the morgue, checking a toe tag. No one knew about the box in my bag, its cardboard edges digging into my hip every time I shifted my weight.

Inside, the theater lights were low, the stage set with two armchairs and a small table holding water glasses. A large screen behind them looped the same video clip I had already seen too many times: Mark looking straight into the camera, saying, “Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is walk away and never look back.”

The audience clapped when he walked onto the stage. He wore a dark blazer, no tie, the uniform of someone who wants to look professional without being intimidating. His hair was perfectly in place, his smile controlled. I tried to see the boy his father had written to in those unsent letters. All I could see at first was the man the world saw.

“Thank you for coming,” he said, settling into the chair with the ease of someone used to being watched. “Tonight isn’t about my father. It’s about yours. Or your mother. Or whoever taught you love with their hands and their silence and their rage.”

A murmur moved through the crowd. People nodded, shifted, reached for tissues tucked into pockets. This was a room full of nerves already exposed before he opened his mouth.

He told his story in carefully chosen pieces. The smell of whiskey in the hallway. Holes in the drywall that stayed for months like warnings. His mother sleeping with her car keys in her hand. The way his father would slam cabinet doors, never quite hitting anyone but always making sure everyone knew he could.

He did not mention war or diagnoses. He did not mention medals or discharge paperwork. The word “veteran” appeared exactly once, as an aside. “He brought the war home and set it at the dinner table with us,” Mark said. “I stopped saluting anything a long time ago.”

The audience laughed at that, a sad, appreciative sound. I didn’t. I thought of Daniel’s binder, his scribbled reminder to himself: Listen more than you talk. Don’t pretend you know their exact war.

Mark wove in clinical terms—trauma bonding, hypervigilance, generational patterns—but always circled back to the same point. “You do not owe your well-being to the person who hurt you,” he said. “It is not your job to make their ending neat.”

He talked about the night he left home for good, suitcase packed by his mother and placed by the back door. He described looking back at the house and seeing a figure in the window, his father’s silhouette or maybe his own reflection. He decided that day he would never go back, even if the man in the window sobered up and apologized on his knees.

“You can outgrow people without waiting to see if they grow,” he said. “Sometimes your survival depends on assuming they won’t.”

The crowd applauded again. It was hard to argue with that. I didn’t want to argue with that. I had sat with enough clients who had gone back one last time and left in handcuffs or an ambulance. I believed him when he said leaving had saved his life.

But I also knew about a storage unit full of years that he had chosen not to see.

During the Q&A, a woman stepped up to the microphone and asked, “What if they really do change? What if they’re in recovery and helping other people, but you still don’t feel safe around them?”

Mark didn’t hesitate. “You are allowed to honor their change without inviting it into your living room,” he said. “You can say, ‘I’m glad you found a better path,’ and still keep your distance. Their redemption story does not require your participation.”

Heads nodded around me. Pens scribbled. That quote would be on social media within the hour.

At the edge of the stage, in the dim light near the exit, I saw a girl sitting halfway up the aisle, knees pulled up, arms around them. She had dark hair pulled into a loose ponytail and the kind of weary eyes I only expect to see on older faces. Every time the audience laughed, she didn’t. Every time they nodded, she just watched her father.

When the crowd stood for a final ovation, she stayed seated. It was only as people filed out that she stood and turned toward the aisle, and I saw the name tag clipped to her jacket.

LILY HARLAN.

She caught me looking at the laminate badge, then at her, then at the stage where her father was shaking hands and posing for photos. For a second, our eyes met. There was a flicker of something like recognition when she saw the county seal on my ID lanyard.

She stepped aside to let people pass, but she didn’t follow them. Instead, she moved closer to the stage, hovering in the shadow of the curtains as if she were waiting for the right moment to step into a conversation too big for the room.

I felt the weight of the box in my bag again, heavier than its size justified. For Mark, it might be an unwanted intrusion. For Lily, it might be a missing chapter. For me, it was a decision I was not qualified to make.

I waited near the exit, watching father and daughter from a distance. He was thanking people for coming, promising new episodes, new books, new tools to help them keep their distance from pain. She was silently watching the man whose story had become their livelihood, whose absence had become their brand.

When the last fan walked away and the staff turned the house lights up, Lily finally approached him. I couldn’t hear their words over the rustle of people leaving, but I saw her hand brush the edge of his sleeve, saw his shoulders tense, saw her mouth form a question that made his jaw clench.

In that moment, I understood something I hadn’t quite put together until then. The next chapter of this story wasn’t about a dead man in a motel or a wall of photos in a storage unit. It was about what his living son and granddaughter would do with the truth once it refused to stay buried.

And whether I liked it or not, I was already standing too close to walk away.

Part 4 – Unattended Deaths and Unattended Truths

The next morning, Daniel’s file was waiting on my desk with a yellow sticky note on top.

“Cremation scheduled for Friday. Status: unattended. Please finalize inventory,” it read in my supervisor’s tight handwriting. The word “unattended” sat on the page like an accusation, even though it was just a category in our system.

In the database, his case number sat between a man with no known family and a woman whose next of kin lived three states away and hadn’t returned a single call. It was a list meant to keep things organized, but on mornings like that it felt more like a ledger of people who had slipped through the cracks.

I took the file to my supervisor’s office. Ms. Patel was already typing, headset on, eyes flicking between two monitors. She waved me in without pausing.

“About Harlan,” I said, holding up the folder. “Do we have to mark the cremation as unattended?”

She slid her headset down to her neck and looked at me over her glasses. “His son declined services,” she said. “No one else has legal standing to request a ceremony. You know that.”

“I know,” I said. “It’s just… he had a community. A lot of them. They’re organizing some kind of gathering. Would it be possible to delay the paperwork a week so they can coordinate something formal?”

Her eyebrows lifted. “Elena, we are not in the business of informal extensions. The cooler space is limited, the budget is tight, and the rules are there for a reason. If his next of kin doesn’t want a service through us, that’s the end of it.”

“What if a veterans’ group offered to pay?” I pressed. “Out of their own funds. No cost to the county.”

“Then they can write a check to the crematorium like everyone else,” she said. “But the legal next of kin has already chosen the cheapest option, and he has that right. We can’t override a living relative because other people feel differently.”

I bit back the urge to say that sometimes “other people” were the ones who had actually been there at the end. Instead, I nodded. “Understood.”

She softened just a fraction. “I know this part is hard,” she said. “You care too much. It’s one of the reasons you’re good at this and one of the reasons you burn out. Finish the inventory. Process the paperwork. If his community wants to grieve him, they’ll find a way to do it without our stamp.”

On my lunch break, I found myself driving back to Northside Storage. The manager barely glanced up when I flashed my badge; I was just another bureaucrat in a line of them who’d been in and out over the years. Unit 37 felt cooler than it had the first time, the dust less strange and more familiar.

I told myself I was there strictly to document his belongings properly: the clothes, the notebooks, the framed certificates folded into boxes. The reality was that I wanted to stand in front of that wall again and remind myself that the word “unattended” didn’t tell the whole story.

I had just finished taking photos for the property form when I heard footsteps in the corridor. A moment later, a head poked around the raised door. It was the man with the scar along his jaw from group, cap still crumpled in one hand.

“Hope I’m not intruding,” he said. “The lady at the clinic said you might be here. Some of us wanted to see the place.”

Behind him, others appeared in ones and twos. The gray-haired woman. The young mother from one of the photos, baby now toddling and clutching her hand. A tall man with a service dog pressed close to his leg. They stood at the threshold like they were afraid to step on something sacred.

“It’s your space as much as his,” I said, stepping back. “Just don’t move anything too drastically. I still have to record it.”

They shuffled in slowly, voices dropping to whispers. Someone exhaled a low whistle at the sight of the wall. The little boy looked up at the photos and pointed.

“Mom, that’s you,” he said proudly. “With me when I was tiny.”

She laughed, a wet sound that was half sob. “Yeah, baby,” she said. “Doc took that.”

Scar-Jaw, whose name I still didn’t know, pulled out his phone. “The guys who couldn’t make it tonight asked if we could show them,” he said. “Just for the group chat.”

I hesitated, then nodded. “Just keep it off public sites, okay?” I said reflexively, though I knew that once a story left a room, it had a way of traveling however it wanted.

He angled the camera toward the wall, his voice low and steady as he explained the cardboard sign, the boxes, the way Daniel had kept track of every tiny win as if it were a medal. People began to speak up from behind him, offering their own short stories.

“He called me every day for a week when my sponsor relapsed.”

“He sat with my wife while I was in surgery because she didn’t want to be alone with her fear.”

“He brought me coffee the first time I went twenty-four hours without shaking.”

At one point, someone nudged me forward.

“This is Elena,” the gray-haired woman said. “She’s the one who made sure we found all this. Say something.”

I wanted to vanish into the concrete, but a dozen hopeful faces were turned toward me and the phone.

“I just do the paperwork,” I began, then stopped because it sounded wrong. “I work for the county,” I corrected. “I see a lot of files. Not all of them look like this. I just thought… it would be wrong for you not to know the rest of his story.”

Scar-Jaw nodded and ended the recording. “They’re gonna want to see this,” he said, more to himself than to me.

We stayed there longer than I should have allowed. People brought in folding chairs from their cars, someone set a coffee thermos on an overturned crate, and for a little while the storage unit felt less like an archive and more like a cramped chapel. They didn’t pray, at least not in any formal way. They just sat in the presence of each other and the evidence that a man they’d relied on had existed, had tried, had cared.

When I left, the sky was bruised purple again. My phone buzzed in my pocket with messages before I even turned the ignition. At home, after I kicked off my shoes and reheated something that barely qualified as dinner, I finally looked.

The video from the unit had not stayed in the group chat. That much was obvious from the view count. Someone had shared it with a friend, who shared it with a cousin, who posted it with the caption, “This is what real service looks like. My dad wouldn’t be here without this man. County won’t give him a proper funeral. So we will.”

A cropped frame of the wall filled my screen, the words ALIVE TODAY BECAUSE OF DOC front and center. The comments were already stacked deep.

“Who is he?”

“Is this about the same guy that therapist talked about on that podcast?”

“If so, I’m confused.”

“People can be heroes to some and monsters to others. Both can be true.”

“Stop trying to guilt kids into forgiving their abusers.”

“Maybe stop deciding someone’s whole life from a clip.”

Thread after thread followed the same pattern. Pain, defensiveness, gratitude, anger. Social media has a way of turning everything into a debate, even grief.

A new post slid into my feed, this time from Mark’s verified account. It was a text-only square on a neutral background, clearly designed, clearly deliberate.

“I am aware,” it began, “that some of my father’s peers and the people he supported are sharing stories about the good he did in their lives. I want to be very clear: their experiences are real and valid. So is mine.”

He went on to say that he would not be attending any gatherings for his father, would not be changing his stance, and would not be engaging in public arguments with people his father had helped. “You can honor the person who showed up for you,” he wrote, “without asking me to rewrite the terror of my childhood. Healing does not require me to participate in his redemption narrative.”

The comments under that post were just as divided. Some praised his boundaries. Others accused him of being selfish, ungrateful, cruel. People who had never met any of them were drawing lines, picking sides, turning a complicated, messy reality into a contest.

I set my phone down, suddenly exhausted. The last thing Daniel had asked for in his letter was that “his guys” not be left wondering why he disappeared. He had not asked for a debate, or a movement, or headlines. He certainly hadn’t asked to become an accidental symbol in an argument about forgiveness.

The next morning, I found an email in my inbox from an address I didn’t recognize. The subject line read, “Question about unclaimed veteran case.”

“Ms. Cruz,” it began, “my name is Jamie Rhodes. I’m a reporter for the local paper. Several veterans have reached out to me about a man named Daniel ‘Doc’ Harlan. They say he died without a proper service. I’ve seen a video from his storage unit. I’m working on a story about how communities step up when the system treats people as numbers. I would appreciate any context you’re allowed to provide.”

There was a line about respecting privacy, another about not wanting to cause trouble for my department. At the bottom, a phone number I could call “on or off the record.”

I stared at the screen for a long time. My cursor hovered over “reply” and then backed away like it had touched something hot.

On one hand, I knew what Ms. Patel would say. “We don’t talk to the press about individual cases. We don’t turn people’s deaths into clickbait. Let the paperwork be what it is.” On the other hand, I had seen what happened when only one version of a story made it into the public square.

The storage unit key sat on my desk beside Daniel’s file, its metal surface catching a strip of morning light. Somewhere between that key, the cardboard sign, and the two posts now echoing against each other online, the truth had become bigger than any of our forms.

I closed the email without replying. Not yet.

Instead, I walked down the hall to Ms. Patel’s office and told her about the reporter. She pinched the bridge of her nose.

“Of course they found you,” she said. “You’re listed on half our public-facing documents. I’ll send a standard response. You do not reply. You do not speak to anyone on or off the record. We are not going to get dragged into some emotional spectacle.”

Her words weren’t unkind, just firm. For the county, this was a question of liability and precedent. For the veterans planning a potluck memorial in a storage facility, it was about saying goodbye to someone who had sat in their driveways at midnight.

On my way back to my desk, my phone buzzed again. This time it was a text from an unknown number.

“Hi, this is Nate from Wednesday group,” it read. “Scar on my face, talked your ear off. We’re putting together something for Doc this weekend. We’re calling it a ‘goodbye cookout’ because he’d make fun of us if we called it anything fancier. You don’t have to come. But he’d want you there.”

I stared at the message, thumb hovering over the keyboard. I thought of Ms. Patel’s warning, of Mark’s post, of the comment threads full of strangers arguing about who had the right to feel what.

“Send me the details,” I typed back before I could talk myself out of it.

I didn’t know then that a shaky live stream from that cookout would end up embedded in Jamie Rhodes’ front-page story two days later. Or that a single quote from one of the men flipping burgers in the rain would ricochet across the internet and land squarely in Dr. Harlan’s inbox.

All I knew was that a man our system had labeled “unattended” was about to have far more company than anyone in the county office had planned for.

Part 5 – The Goodbye Cookout in the Rain

The goodbye cookout was held in the kind of park you only notice when someone tells you to meet them there.

There was a rusted playground, a few leaning picnic tables, and a concrete shelter with a roof that leaked in two corners. By the time I arrived, smoke from two dented grills hung under the overhang, clinging to jackets and hair. Kids chased each other in the damp grass, their laughter jarring against the knot of grief I carried in my chest.

I parked farther away than I needed to and sat in the car for a minute, watching. Men and women drifted between the tables, plates in hand, stopping to hug, clap shoulders, pass napkins. Someone had taped a handwritten sign to a post. “Doc’s Last Cookout – Bring Stories.”

Nate, the man with the scar along his jaw, spotted me first. He lifted his baseball cap in a half-salute. “You came,” he said when I reached the shelter. “He would’ve told you this was a waste of a perfectly good Saturday, but he’d have shown up anyway.”

“I brought cookies,” I said, holding up the plastic container from the grocery store. It felt ridiculous and small compared to the wall of photos in my memory, but food is its own language at gatherings like this.

“They’re perfect,” he said. “He had a terrible sweet tooth he pretended not to have. Come meet everybody.”

He introduced me around. Linda, the gray-haired woman from group, was arranging plastic cutlery. Tasha, the young mother whose picture I’d seen with a baby and a dog tag, was trying to keep that baby—now a toddler—from drinking rainwater out of a paper cup. A man in his seventies with a cane and a chest full of invisible weight sat at the end of a bench, watching everything with sharp eyes.

Near one of the picnic tables, a phone was propped on a folding chair, leaning against a water bottle. The screen showed a growing list of names as people joined a live video. The title read, “For Doc – If You Can’t Be Here, You’re Still Here.”

“We’ve got guys tuning in from three states,” Nate said, following my gaze. “Some can’t drive. Some can’t leave their houses. Some just… can’t handle crowds. We figured this is the next best thing.”

“Is that public?” I asked, my bureaucratic reflex flaring.

“Just to the private group,” he said. “Unless somebody screenshots it, which they probably will. But we’re not dragging you or the county into it. This is ours.”

Relief and worry tangled in my stomach. I wasn’t there as an official representative. I wasn’t there as anything, really, except a person who had opened a door and found a man’s life taped to the wall.

Jamie arrived about twenty minutes after I did. She was younger than I expected, with a press badge clipped to her jacket and a notebook already in her hand. Nate greeted her with the ease of someone who had decided she was safe.

“This is the reporter I told you about,” he said, waving her over. “She’s not here to make us look foolish. She’s here because she was the only one who called back and didn’t ask us how to spell PTSD.”

Jamie smiled and extended her hand to me. “You must be Elena,” she said. “I recognize you from the way everyone talks about you.”

My shoulders tensed automatically. “I can’t comment on county procedures,” I said. “My boss was very clear.”

“I’m not asking you to,” she replied. “I’m interested in the gap between what the system can do and what people end up doing anyway. ‘Unnamed county employee’ is more than enough for that.”

For the next hour, the cookout unfolded the way these things always do. Burgers flipped. Hot dogs rolled dangerously close to the edge of the grill. Someone spilled soda; someone else remembered napkins a beat too late. Children climbed onto laps that had once held rifles. Dogs hovered under tables, hoping for dropped chips.

And in between all of that, people talked about Daniel.

They did it without speeches at first. Just memories slipping into conversation the way you’d mention the weather. “Doc told me not to buy that car, and he was right, it died in a week.” “Doc made me return the whiskey I put in my cart at the grocery store once. Stood there with me while I explained to the cashier that I’d changed my mind.” “Doc wouldn’t let me sit on the end of the row because he said that’s where you sit when you’re planning to leave early.”

Eventually, someone nudged Nate toward the phone on the chair. “Say something,” Linda urged. “For the people who can’t smell this smoke.”

He scrubbed a hand over his jaw and faced the camera. “Hey, knuckleheads,” he said. “You know who you are. We’re out here eating food he would’ve criticized and telling stories he would’ve rolled his eyes at.”

A few people chuckled. The comment count ticked up.

“You already heard the basics,” Nate went on. “Doc’s gone. The county is doing what they do. But we’re here because we refused to let the word ‘unattended’ be the last thing written under his name.”

He glanced at me for half a second, then back at the camera.

“I know some of you saw that therapist clip,” he said. “The one where his son called him a monster. I’m not here to argue with that. I wasn’t in that house. I don’t know what he was like when he was drinking and trying to outrun what happened overseas. I believe that kid when he says it was bad. We all know what bad can look like.”

The park seemed to hold its breath. Even the kids quieted for a moment, as if the air itself had shifted.

“But here’s what I do know,” Nate continued. “My boys have a father today because Doc answered the phone the night I almost made a choice I couldn’t take back. Linda’s grandkids have pictures with her at their birthdays because Doc sat with her in a parking lot instead of letting her drive off angry. Tasha’s little one there calls him Uncle Doc even though he never met him, because his name is in half their bedtime stories.”

He took a breath, eyes bright.

“He wasn’t a hero instead of being a monster,” Nate said slowly. “He was both. He was the man who broke his family and the man who spent the rest of his life trying to keep other families from breaking. We’re not here to erase what he did. We’re here because we are the proof of who he tried to die as.”

Linda reached out and squeezed his arm. Someone behind me sniffed hard. On the phone screen, the comments poured in. “Thank you for saying that.” “Both can be true.” “I wouldn’t be here to annoy my kids without him either.”

Jamie’s pen scratched furiously across her notebook. She circled something, underlined something else, lips pressed tight like she was trying not to react too visibly.

I moved closer to the edge of the shelter, letting the drizzle hit my face. It felt like a small punishment for how tangled my role had become. I was there because of my job. I was there despite my job. Both could be true, too.

When the trays of food were mostly empty and the fire in the grills had died down to coals, Jamie asked if she could talk to people individually. Some declined. More said yes. She was careful, her questions open-ended. “How did you meet him?” “What do you wish people knew?” “What difference did he make in your week, not just your life?”

At some point, she turned to me. “Off the record,” she said, voice soft. “What went through your mind the first time you saw that wall?”

I opened my mouth to give a safe answer and found something else coming out instead. “Our system has boxes for ‘hero,’” I said. “And boxes for ‘problem.’ It doesn’t have a box for men like him. But the people here do.”

She nodded. “That’s your quote,” she said quietly. “With or without your name.”

By the time I got home, my clothes smelled like smoke and onions and rain. I put them straight in the washing machine and stood in the laundry room in my bare feet, listening to the water rush in. I told myself I would check emails before bed, nothing more.

The story went online just after midnight.

“He Died Alone in a Motel,” the headline read. “A Storage Unit and a Park Full of Strangers Say He Didn’t Die Alone.” Underneath was a photo Jamie had taken of the wall in Unit 37, the cardboard sign front and center, faces surrounding it like a congregation.

She didn’t use my name. She called me “a county worker who requested anonymity because she was not authorized to speak to the press.” She quoted Nate’s line about hero and monster in full. She described the cookout, the kids, the way people laughed through tears. She mentioned Mark’s posts and gave them their own space instead of pitting them head-to-head.

“It may be,” she wrote, “that the truth about Daniel ‘Doc’ Harlan lives in a place our public conversations aren’t very good at reaching yet: the space where someone can cause real harm and later do real good, and where both realities are allowed to stand without canceling each other out. His son has a right to his distance. These veterans have a right to their gratitude. Somewhere between them lies a story we rarely make room for.”

By morning, the article had been shared far beyond our small city. Bigger outlets picked it up, some just copying the text, others adding commentary. Screenshots of the wall and the cardboard sign traveled faster than any official obituary ever could.

Nate’s quote became a pull line superimposed over black-and-white images of saluting silhouettes. “He wasn’t a hero instead of being a monster. He was both.” People argued about it, used it as proof for their side, or sat with it quietly.

Under one repost, someone had tagged Mark directly a dozen times. “Care to comment?” they wrote. “Is this your dad?” “Does this change anything?”

That afternoon, Mark posted again.

“I’ve seen the article about my father,” he wrote. “I’m glad he was able to show up for people in ways he never did for us. I don’t dispute the good he did. I also don’t rescind a single word I’ve shared about the harm he caused. If you’re looking for me to join in a public conversation about his legacy, I will not. My healing is not a public vote.”

His tone was calm, measured. Still, there was an edge under the words that hadn’t been there before, like someone bracing for an impact they knew was coming anyway.

Later that evening, my phone buzzed with another unknown number. For a second, I thought it might be another reporter, another request for a quote I wasn’t supposed to give.

Instead, the message was short.

“Hi. My name is Lily Harlan,” it read. “I think you’re the one who found my grandfather’s things. I saw his wall in that article. I saw my mom in one of those pictures. I need to see the rest. Please.”

Part 6 – The Granddaughter Who Wanted the Whole Story

Lily’s text sat on my screen like a live wire.

“I think you’re the one who found my grandfather’s things. I saw his wall in that article. I saw my mom in one of those pictures. I need to see the rest. Please.”

Seeing her name typed out felt different than seeing it sharpied on a cardboard box. Lily Harlan. The girl in the theater with her knees pulled to her chest, watching her father talk about walking away forever. The girl whose existence had kept Daniel sober on days when nothing else did.

I didn’t answer right away. I set the phone face down on my kitchen table and stared at the ceiling, listening to the refrigerator hum and the upstairs neighbor’s television bleed through the floor. Every path I could take from that message seemed to end with someone angry, someone hurt, or me sitting in front of Ms. Patel’s desk being reminded of the words “not authorized.”

In the morning, I found out my hesitation had bought me exactly eight hours of peace.

“Elena,” Ms. Patel said from my doorway, voice clipped. “My office. Now.”

She had the article open on her screen when I stepped in. The photo of the wall in Unit 37 filled half the monitor, the headline stretching across the top. She didn’t invite me to sit.

“Would you like to tell me,” she asked quietly, “why a reporter quoted an unnamed county worker who sounds exactly like you?”

My pulse thudded in my ears. “She came to the cookout,” I said. “I told her I couldn’t speak on the record about procedures. I didn’t give her your name. I didn’t give her mine.”

“But you spoke,” she said. “Even off the record, your observations can be attributed. You know how this works.”

Her disappointment bothered me more than her anger would have.

“I didn’t tell her anything confidential,” I said. “I didn’t give her access to files. I just… answered a question about the gap between the system and the community.”

She took off her glasses and rubbed the bridge of her nose. “You are good at your job because you see the people behind the paper,” she said. “But you still have a job. The county cannot become the villain in a story about a veteran who died alone. Do you understand that?”

“Yes,” I said.

“In that case,” she went on, “you will finish Mr. Harlan’s paperwork exactly as required. You will not visit that storage unit again unless it is to catalog property. You will not attend any more unofficial events in any professional capacity. And you will not, under any circumstances, communicate with the press about this or any other case. Clear?”

“Clear,” I said, even though nothing felt that way.

Once back at my desk, I finally replied to Lily’s message before I could talk myself out of it.

“Hi, Lily. Yes, I’m the one who found the storage unit. I’m sorry you had to see your mom that way by surprise. There are more things there connected to you and your dad. I need you to know that seeing them could be… complicated.”

Her response came fast.

“Complicated compared to what?” she wrote. “Compared to growing up being told my grandfather was dead? Compared to watching my dad’s followers tag me under every post about this?”

A second bubble popped up before I could type.

“He’s furious about the article,” she added. “He says it’s trying to guilt him. He told me not to get involved. That’s why I texted you from a number he doesn’t have. I’m eighteen. I get to decide if I want to know who this man was. Don’t I?”

I stared at that last sentence for a long time. I thought of all the times I’d sat in fluorescent rooms with families who never got the chance to decide anything, because the body in the bag was already in the ground by the time someone found an old address book.

“Yes,” I typed slowly. “You do.”

We agreed to meet in a coffee shop near the university, neutral ground with bad lighting and decent muffins. I got there early and picked a table in the corner, back to the wall out of habit, where I could see the door. When Lily walked in, I recognized her immediately even without the name tag.

She looked both younger and older than she had in the theater. Younger, because her hair was pulled back in a messy bun and she wore an oversized hoodie with a faded logo. Older, because there were dark half-circles under her eyes and a tension in her jaw that didn’t belong on a teenager.

“Hi,” she said, sliding into the seat across from me. “I’m Lily. Obviously.”

“Elena,” I said. “Thank you for coming.”

She wrapped both hands around her coffee cup like she needed its heat to stay upright. “I almost didn’t,” she admitted. “My dad keeps saying this is a distraction. That people are trying to rewrite his story. But then I saw my mom’s face on that wall.”

Her voice wobbled for the first time.

“She told me she burned all the pictures of him,” Lily said. “Said she didn’t want me growing up wondering what I missed. But there she was, in your storage unit, smiling next to a man I’ve only ever seen as a shadow in the background of my dad’s trauma talks.”

I let the silence sit for a moment. She didn’t rush to fill it; she had learned how to hold space with discomfort, same as her father.

“What do you want from me?” I asked gently. “Not what your dad wants, not what the internet wants. You.”

She stared into her coffee. “I don’t know,” she said. “Part of me wants you to tell me it’s all fake, that the wall is a stunt, that the veterans are confused. That would make it easy. I could go home and keep hating him for the right reasons.”

“And the other part?”

“The other part wants to tear open every box with my name on it,” she said, eyes flashing. “I want to read every page he ever wrote about me. I want to know if he actually loved me or if they’re just saying that because they need him to be good.”

Her honesty was sharper than anything I could have phrased.

“There is a box in the unit labeled ‘For Mark and Lily,’” I said quietly. “I haven’t opened it yet. I thought it should be your choice. And your father’s. Together.”

She let out a short, bitter laugh. “You’ve met my father,” she said. “Do I seem like someone he shares choices with?”

I thought of him on stage, of the certainty in his voice when he said he would never look back, not even if the man on the porch sobered up and begged.

“Lily,” I said carefully, “I can bring you there. I can use my key and let you stand in front of that wall yourself. But I can’t guarantee what it will do to your relationship with your father. And I can’t protect you from whatever you find in that box.”

She took a slow breath. “He’s already furious at me,” she said. “I asked him if it was possible he missed something. He said that was a betrayal. That if I started ‘romanticizing’ his father, I was choosing the abuser over the victim.”

Her eyes filled and she blinked hard. “I’m his kid too,” she whispered. “Why do I only ever get to be evidence?”

The question hung between us, raw and unfair and true.

“Whatever you decide,” I said, “I’ll back you up with the truth. If he asks whether I showed you anything, I’ll tell him you asked, and that you’re an adult, and that you deserved to see what was left with your name on it. He won’t like it, but he won’t hear a lie.”

She nodded, set her cup down with a little more force than necessary, and straightened. “Then I decide yes,” she said. “I want to see where he spent the part of his life I was told he didn’t have anymore.”

The drive to Northside Storage felt shorter with her in the passenger seat, even though traffic was thicker. She watched the city roll by like it belonged to someone else.

“He used to bring me to parks like that,” she said suddenly, nodding toward a playground as we passed. “We’d stay until it got dark. My mom hated it. She said we were making memories with a time bomb.”

I didn’t know what to say to that, so I didn’t say anything. Sometimes silence is the only thing that doesn’t sound like advice.

At the storage facility, the manager looked up when I walked in. His eyes flicked from my badge to Lily’s face and back again. He didn’t ask questions. People who work around other people’s secrets learn not to.

Inside the maze of metal doors, our footsteps echoed. Lily shoved her hands into her hoodie pockets, shoulders hunched against the chill.

“What was he like?” she asked quietly as we walked. “Not then. Recently. When you saw his room.”

“Neat,” I said. “Careful. There was a Bible open on the nightstand and a hotline card as a bookmark. He had a note with the storage unit key asking me to tell ‘his guys’ he didn’t just disappear.”

She swallowed hard. “That sounds like him,” she murmured. “At least, the version I’ve been reading about for the past week at three in the morning.”

We stopped in front of Unit 37. The metal door looked the same as it always had, indifferent to the fact that it had become a kind of altar online. I pulled the key from my pocket, feeling its familiar cool weight.

Before I could slide it into the lock, Lily’s phone buzzed. The sound was loud in the narrow corridor. She glanced at the screen, jaw tightening.

“It’s my dad,” she said. “He keeps calling. Ever since I left the house.”

“Do you want to answer?” I asked.

She stared at the name for a long second. The phone buzzed again, then stopped. A few moments later, a text appeared. I couldn’t see the words, but I saw the way her shoulders flinched.

She turned the screen toward me. The message was short.

“Do not meet with that county worker,” it read. “Do not let them manipulate you with his ‘good deeds.’ You are walking into something you will regret.”

Lily’s eyes filled, but her voice was steady when she spoke.

“I think,” she said, “that I’m already in something I regret. I just don’t want my regrets to all be about what I never dared to look at.”

She slid the phone back into her pocket and nodded at the lock.

“Please open it,” she said. “If I’m going to carry this story for the rest of my life, I want to at least know how it actually starts.”

The key turned in the lock with the same small, decisive click as always. The door rattled upward, and the smell of dust and cardboard washed out over us. I reached for the chain of the bare bulb and paused.

“You ready?” I asked.

“No,” she said honestly. “But do it anyway.”

I pulled the chain. Light flickered to life, circling the room, catching on photos, boxes, and that strip of cardboard on the back wall.

Lily stepped forward, shoulders squared against whatever she was about to find, and crossed the threshold into the secret world her grandfather had built in the years her father had spent trying to forget he existed.

Part 7 – Letters to Ghosts: Mark and Lily Open the Box

Lily stepped into the unit like someone walking onto a stage she hadn’t agreed to perform on.

Her eyes went straight to the back wall. For a second she just stood there, staring at the cluster of photos and the crooked strip of cardboard. Her lips moved as she read the words silently. Then she said them out loud, barely above a whisper.

“Alive today because of Doc.”

She took a few more steps forward. I watched her shoulders rise and fall, too fast, then slow down as she forced her breathing to match the pace of her feet. She stopped in front of a photo of Linda holding her grandkids, fingertips hovering just above the curling edge.

“That’s the woman from the article,” she said. “The one who said he sat with her in the parking lot.”

“That’s Linda,” I said. “She’s the one who called it a ‘waste of a perfectly good Saturday’ when they planned the cookout. Then she baked three pies.”

A ghost of a smile tugged at the corner of Lily’s mouth and disappeared. She moved along the wall, scanning faces like she was afraid and desperate to recognize someone. Halfway down the row, she stopped again.

“That’s my mom,” she breathed.

The photo showed a younger version of her mother, hair longer, laugh lines softer, leaning against a pickup truck. Daniel stood next to her, not touching, hands in the pockets of a faded jacket. They were both squinting into the sun.

Underneath, in Daniel’s shaky block letters, were the words, “Six months sober. Promised her I’d stay away until I deserved to be near her kid again.”

Lily reached out and touched the caption like it might vanish. “She never told me they saw each other after he left,” she said. “She said the last time she saw him was the night we moved out.”

“She may have her reasons for remembering it that way,” I said gently. “Memory does strange things with pain.”

Tears filled Lily’s eyes, but she blinked them back with a small, violent shake of her head. “Is there anything of mine up there?” she asked. “Or was I just… theoretical to him?”

“There’s a box,” I said, nodding toward the low shelf near the door. “I told you about it. ‘For Mark and Lily.’ I didn’t open it without you.”

She tore her gaze from the wall and walked over to the shelf. Up close, the duct tape label looked even more makeshift, like he’d written it in a rush and then stared at it for a long time before putting the lid on.

“Is this evidence?” she asked suddenly. “Like, legally? Am I allowed to touch it?”

I thought of Ms. Patel, of policies and forms and checklists that never once mentioned boxes for estranged grandchildren. “His will wasn’t complicated,” I said. “He didn’t have much. He left a note asking that certain things go to specific people, if they ever came. I’d say this qualifies.”

Lily took a breath, slid her fingers under the edge of the tape, and peeled it back. The box gave a soft cardboard sigh as she lifted the lid.

Inside, everything was wrapped in layers of old T-shirts, as if he’d run out of packing paper and used what he had. On top of the bundle sat a small, battered stuffed bear wearing a faded junior sports team shirt. One of its button eyes had been stitched back on with dark thread.

“I had one just like this,” she whispered. “When I was little. Mom said we lost it during a move.”

There was a Post-it stuck to the bear’s shirt. In Daniel’s handwriting, cramped but legible, it read, “Bought one for her, then another for me when I couldn’t give the first. Kept this one so I wouldn’t forget why I needed to stay sober.”

Lily pressed the bear to her chest for a moment, eyes squeezed shut. When she opened them, her jaw was set in that same stubborn line I’d seen on Mark’s face onstage.

Underneath the bear were stacks of envelopes. Some were addressed “Mark” in careful print. Some said “Lily” in a looser script that grew steadier over time. None of them had stamps. None of them had been opened.

“Do you want me to give you privacy?” I asked. “I can wait outside.”

She shook her head. “No,” she said. “If I do this alone, I’ll convince myself I imagined it later. I want a witness that this actually exists.”

She picked up the first envelope with her name on it. The date in the corner was from fifteen years ago. She slid a finger under the flap, opened it, and unfolded the lined paper inside.

“Dear Lily,” she read. “You don’t know me. You’re three years old today. Your dad sent a picture once, before he changed his number. You were holding a birthday cupcake with blue frosting and looking at it like you weren’t sure it was safe to trust. I know that look.”

Her voice shook but didn’t break.

“I have been sober for one year and four months,” she continued. “That means I have been sober for the entire time you were old enough to remember me if I had been allowed to be there. I am writing this instead of calling so I don’t break the promise I made to your mom to stay away until she says otherwise. I don’t know if she ever will. I don’t blame her. I earned her fear. I just want you to know that somewhere out here, there is a man who used to be your grandfather in all the wrong ways, trying very hard to become one in the right ways, even if only on paper.”

She stopped and stared at the words, her thumb rubbing at a wrinkle in the page.

“He sounds like he’s writing to a ghost,” she said.

“He was,” I said softly. “At least from his side.”

She picked up another letter, dated the year she started school. The handwriting was a little more confident, the tone a little more grounded.

“Dear Lily,” it read. “You start kindergarten today. I picture you with a backpack bigger than you are. I do what I do on Wednesday nights so that some other kid’s backpack doesn’t have to be stuffed with things they can’t explain. I still don’t know if I will ever hear your voice, but hearing the guys talk about their kids makes me feel like I am paying off a debt I can never fully clear.”

She flipped to the end.

“If your dad ever shows you these,” Daniel had written, “I want you to hear this from me, not from an article, not from a stranger: the best thing about my sobriety is that it kept me from showing up at your door and asking you to carry my amends. I don’t know if that makes me courageous or cowardly. I just hope it makes your life a little quieter than your dad’s was.”

Lily let out a sound that was half laugh, half sob. “Too late,” she said. “My life is built on his loudest stories.”

We went through letter after letter. Some were short—“Still sober. Still at group. Still imagining you rolling your eyes at me if we ever meet.” Others were longer, full of details about people from Wednesday nights whose names he changed but whose struggles he described with a tenderness that didn’t match the word “monster.”

Occasionally he mentioned Mark directly.

“I saw your dad on a flyer today,” one letter said. “He’s doing good work. He is helping people name the damage I caused. I am proud of him and gutted by him at the same time. If you are in his office someday, please listen to him. He knows what he’s talking about. He paid for that knowledge with his childhood.”

In another, written the year Lily turned thirteen, he wrote, “If you’re anything like your dad and your grandmother, you’re stubborn. That’s good. It means you might be strong enough to hold the idea that I am not just one thing. But even if you can’t, even if you never want to know more than the worst thing your father remembers, I won’t argue. I don’t get to write my own verdict.”

By the time we reached the most recent envelope, dated just six months before he died, Lily’s face was wet and her voice was hoarse. She opened it with hands that trembled.

“Dear Lily,” it said. “You are seventeen now. Old enough that if this ever reaches you, you will be old enough to decide what to do with it. I won’t be the one to put it in your hand. That job belongs to the people who kept you safe from who I used to be. If you’re reading this, it means someone thought you were ready to know that the man who put dents in your dad’s walls also held the hands of strangers so they wouldn’t put holes in their own lives.”

Her shoulders shook. She kept going.

“I don’t ask for your forgiveness,” he wrote. “I don’t even ask for your understanding. I only ask that when you hear people talk about me, you remember that human beings do not stay frozen in the worst thing they have ever done. Your dad’s pain is real. So is the work I’ve done to make sure fewer kids feel it. Both things can sit in your hands at the same time without canceling each other out. If that feels too heavy, put it down. I will not be offended in whatever afterlife exists for men like me.”

He ended the letter with the same small phrase every time.

“Stay safe. Stay kind to yourself. Love, Doc.”

Lily folded the last page slowly, carefully, like she was closing something fragile. She kept her head down for a long time. When she finally looked up at me, her eyes were red but clear.

“He loved me,” she said, voice flat with disbelief. “He loved me without ever meeting me.”

“I think he did,” I said.

“And he hurt my dad,” she added immediately. “He hurt him so badly that my existence is wrapped in warnings about becoming him.”

“Yes,” I said. “Both are true.”

She looked back at the wall, at the faces and the cardboard sign, then at the box in her lap. “My dad always says you don’t owe the person who hurt you the comfort of seeing their change,” she said. “But what about the people who grew up in the shadow of that change? What do we owe ourselves?”

I didn’t have an answer that wasn’t a cliché. I stayed quiet.

Lily began stacking the letters back into the box. When she reached the envelopes addressed to Mark, she paused. “Do you know if he ever saw any of these?” she asked.

“I don’t,” I said. “They were all in the unit when I found it. Unsent.”

She picked one at random. The date was from nearly ten years ago, the year Mark’s first book had come out. The flap had never been sealed.

She looked at me, eyes searching. “I need to know what he didn’t read before I can believe what he did,” she said.

She opened it.

“Mark,” she read quietly. “I saw your face on a billboard today. You looked like your mother when she used to smile for real. I didn’t go to your event. That would have been selfish. You have built something out of the rubble I gave you, and the last thing you need is a ghost lumbering through it. But I wanted you to know that every time you tell someone they deserve safety, I hear it as you telling the child version of yourself that he deserved it too. I am grateful you did the thing I couldn’t. You got out. I am just trying, in my small way, to make ‘getting out’ unnecessary for other kids.”

Lily’s voice broke halfway through. She handed me the page and reached for another, breathing hard, like ripping off bandages.

“He wrote to a version of my dad who would never read it,” she said. “My dad talks to a version of him that never changed. They’ve both been having conversations with ghosts.”

She stacked the Mark letters to one side and the Lily letters to the other. Then she did something I wasn’t expecting. She took a photo of each stack with her phone.

“If he ever accuses me of making this up,” she said, “I want to have proof that I am not choosing a fantasy over his pain. I am choosing the whole picture over one frame.”

Her phone buzzed again on the concrete floor. Another text from her father flashed across the screen. This one was longer. I saw enough of the preview to catch the words “betrayal,” “public spectacle,” and “don’t you dare let them use you.”

Lily stared at it, then put the phone facedown.

“I don’t know how to tell him about this,” she said. “But I know if I keep it a secret, it will swallow me. And if I tell him, it might break something that’s already cracked.”

“That’s a hard place to stand,” I said.

She nodded. “You said you’d back me up with the truth,” she reminded me.

“I did,” I said.

“Then I’m going to need you there when I tell him,” she said. “Because when he looks at me with that ‘I thought you were on my side’ face, I’m going to forget how to say words. And I need someone who’s seen both versions of my grandfather’s life to say out loud that I’m not crazy for wanting to hold both.”

I thought of Ms. Patel, of the word “unattended,” of how many times I’d told myself to stay out of families’ stories once the ink on the forms was dry.

“All right,” I said. “If he asks to meet, I’ll come. I’ll tell him exactly what I saw here and exactly what I’ve heard from the people he helped. I won’t tell him what to feel. That’s between the two of you.”

Lily exhaled, a shuddering breath that sounded like it had been trapped in her chest for years.

“Okay,” she said. “Then let’s go home before I lose my nerve.”

As we turned off the light and pulled the door of Unit 37 down, I had the uneasy feeling that the real inventory I’d taken that day wasn’t of a dead man’s belongings. It was of the fault lines running through a living family, ones that were about to shift whether any of us were ready or not.

Part 8 – Bringing the Dead Man’s Truth Home

When Lily said, “Let’s go home,” she meant her father’s house, not mine.

The drive there felt shorter and longer at the same time. She stared out the window, letters tucked back in the box on her lap, stuffed bear wedged between her knees like a seatbelt. Every time her phone buzzed, she glanced at it and then deliberately turned the screen facedown again.

Mark lived in a quiet neighborhood full of trimmed lawns and tasteful porches. The kind of place where people walked dogs at dusk and waved without expecting conversation. His house matched the others: white siding, black shutters, a wreath on the door that said “WELCOME” in a font that tried a little too hard.

His car was in the driveway. So was another, smaller sedan I didn’t recognize. When Lily saw it, her jaw tightened.

“Mom’s here,” she said. “Great.”

We walked up the path together. Before we could knock, the door swung open. Mark stood there, one hand braced on the frame, the other wrapped so tightly around his phone his knuckles were white. Behind him, in the hallway, a woman I recognized from the photo on the storage unit wall watched us with cautious eyes.

“Lily,” he said, voice sharp. “Inside. Now.”

She didn’t move. “This is Elena,” she said instead. “The county worker who found the storage unit. The one people keep tagging you about.”

His gaze flicked to my badge, then back to her. “We’ll talk about that in a minute,” he said. “Right now, you need to come inside and away from whatever… narrative… they’re trying to sell you.”

Lily lifted the box slightly. “He didn’t sell me this,” she said. “Grandpa packed it himself.”