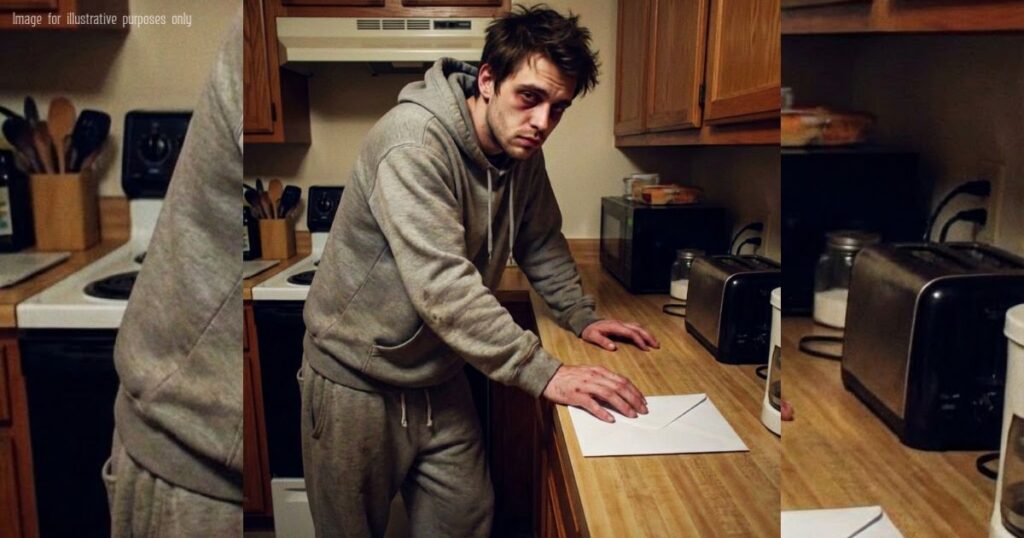

At 6:45 PM last Tuesday, I placed a sealed envelope on my kitchen counter. Inside were the passwords to my bank accounts, a cancellation letter for my lease, and a note for my sister. My apartment was clean. My debts were tallied.

I was twenty-six years old, and I was done.

If you looked at my Instagram, you’d think I was crushing it. I posted photos of my “hustle”—laptop open in coffee shops, captions about the “grind,” filters that hid the dark circles under my eyes. In reality, I was working three gig-economy jobs just to afford a studio apartment in a city that chewed people up and spit them out. I was $40,000 in student debt for a degree I wasn’t using. I hadn’t eaten a hot meal in four days because gas prices went up again.

I was drowning in noise—politics on Twitter, anger on the news, everyone shouting to be heard—yet the silence in my own life was deafening. I was surrounded by millions of people, but I was completely alone.

There was just one loose end. Buster.

Buster is a scruffy, 40-pound terrier mix with one floppy ear. I couldn’t leave him in the apartment alone. I grabbed his leash and his bag of food. I walked down the hall to Apartment 4C.

Mr. Earl’s place.

Mr. Earl is a relic of a different America. He’s an African-American man in his late seventies, a Vietnam vet who spends his evenings sitting on a folding lawn chair on the shared balcony, smoking a pipe and listening to baseball on a crackling AM radio. He doesn’t own a smartphone. He doesn’t care about the algorithm.

I knocked on the metal railing.

“Yeah?” His voice was deep, like thunder rolling in the distance.

“Mr. Earl?” I tried to keep my hands from shaking. “Sorry to bother you. I… I have to leave town. Tonight. Urgent job opportunity in Denver. It came up fast.”

The lie felt like broken glass in my throat. “They don’t allow dogs in the corporate housing. The shelter opens at 8:00 AM. Could you… could you just keep Buster until the morning? I’ll leave a note for them to come get him.”

I held out the leash. Buster, the traitor, wagged his tail and licked Mr. Earl’s hand.

Mr. Earl didn’t take the leash. He turned the radio down. He took a long look at me. Not the polite glance people give you at the grocery store. He looked into me.

“Denver,” he said flatly.

“Yes, sir. Big break for me.”

“You’re lying,” he said.

My heart stopped. “Excuse me?”

“I said you’re lying.” He pointed the stem of his pipe at me. “You ain’t going to Denver, son. You’re wearing sweatpants you’ve had on since Sunday. You smell like stress and cheap coffee. And your eyes… I saw that look in the jungle in ’68. That’s the look of a man who’s about to walk away from his post.”

The air left my lungs. I took a step back. “I just need someone to watch the dog.”

“Sit down,” he commanded. He kicked an empty milk crate toward me.

“I can’t, I have to—”

“I said sit down.”

I sat. I don’t know why. Maybe because for the first time in months, someone actually saw me. Not my profile, not my credit score. Me.

Mr. Earl went inside and came back with two cans of generic soda. He cracked one open and handed it to me.

“Drink.”

We sat in silence for a long time. The city traffic hummed below us. Sirens wailed in the distance.

“You know what went wrong with this country?” Mr. Earl asked quietly. He wasn’t angry. He sounded sad.

“The economy?” I whispered. “Politics?”

He shook his head. “Porches.”

“Porches?”

“We got rid of front porches,” he said, looking at the smoggy sunset. “Back in the day, when the work was done, you sat on the porch. You saw your neighbors. If Bill across the street looked down, you went over. You asked, ‘You okay, Bill?’ We were a tribe. We fought, we disagreed, but we were there.”

He gestured to the phone in my pocket. “Now? You kids carry the whole world in your pocket, but you don’t know the name of the man living ten feet from your head. You built fences instead of porches. You traded community for convenience. And now you’re sitting here thinking if you just disappear, the math balances out. Like you’re just a line item in a budget that needs cutting.”

Tears pricked my eyes. Hot and fast. “I’m just tired, Mr. Earl. I’m so tired of running a race I can’t win.”

“I know,” he said softly. He reached down and scratched Buster’s ears. “I lost my wife, Betty, six years ago. Since then, this balcony is all I got. Some days, the quiet in that apartment is so heavy I think it’s gonna crush my chest. I sit out here hoping one of you young folks will stop. Just to say hello. Just to prove I’m still alive.”

He looked at me. “The dog knows.”

Buster was pressed against my leg, whining. He wasn’t looking at Mr. Earl. He was looking at me.

“You leave tonight, that dog waits by the door for a week. He don’t understand ‘Denver.’ He just understands that his dad left him.” Mr. Earl took a sip of soda. “And me? I gotta be the one to call the pound? I gotta watch them drag him away? That’s a hell of a thing to do to a neighbor.”

The guilt hit me harder than the sadness. I put my head in my hands and sobbed. I cried for the debt, for the loneliness, for the exhaustion.

“I can’t do it anymore,” I choked out. “I don’t have it in me.”

“You don’t have to do it all,” Mr. Earl said. “You just gotta do tomorrow.”

He stood up, his knees popping. “Here’s the deal. My hip is bad. I can’t walk good. But this dog needs walking. You keep the dog. But every morning at 6:30 AM, you bring him here. We drink coffee. Real coffee, not that overpriced junk. I watch the dog while you go to work, or look for work. Then you come back, and you tell me one thing that happened today that wasn’t bad news.”

I looked at him. It wasn’t a check for a million dollars. It didn’t fix inflation. But it was a tether. A rope thrown across the abyss.

“6:30?” I asked.

“6:30 sharp. If you’re late, I’m banging on your door. I’m an old soldier, I wake up early, and I get cranky if I drink alone.”

He held out a hand. It was rough, calloused, and strong. I took it.

“Go home, son. Feed the dog. Tear up the note.”

I walked back to my apartment. I didn’t fix my life that night. The world was still loud. The bills were still there. But I tore up the letter. I unpacked the dog food.

I set my alarm for 6:15 AM.

The next morning, I was there. We didn’t say much. We just watched the sun come up over the city skyline. But for the first time in years, the morning didn’t feel like a threat. It felt like a start.

To anyone reading this who feels like they’re shouting into a void, who feels like they are failing at a game that is rigged against them: You are not a burden.

The isolation you feel is a lie sold to you by a system that profits from your loneliness. We are not meant to do this alone.

Look up from the screen. Knock on a door. Find a porch. The courage isn’t in fighting the whole war by yourself. The courage is in turning to the person next to you and saying, “I’m not okay. Can we just sit for a minute?”

Hold on. The world is a mess, but it’s still better with you in it.

See you at 6:30 AM.

👉PART 2 — “6:30 AM, SHARP”

At 6:29 AM on Wednesday, I stood in my doorway staring at my phone like it was a detonator.

My alarm had gone off at 6:15, just like I promised. I’d barely slept. My brain kept replaying the night before—Mr. Earl’s voice, the torn paper, the way Buster pressed his whole body into my leg like he was trying to hold me together with his ribs.

On my counter, the sealed envelope was still there.

Not because I wanted it there.

Because I was scared of how close I’d gotten to the edge, and I needed to see it with my own eyes to believe I hadn’t stepped over.

Buster whined and spun in circles, leash in his mouth, like the world had never been heavy a day in his life.

I checked the time again.

6:29.

I took a breath that felt too big for my chest, locked my door, and walked down the hall.

At 6:30 AM, Mr. Earl’s door opened before I even knocked.

He stood there in gray sweatpants, a faded T-shirt, and the same expression he wore last night—half annoyed, half relieved—like my life was a job he’d agreed to supervise and he wasn’t about to let me slack off.

“You’re on time,” he said.

“I’m trying,” I muttered.

“Trying is for bowling,” he said, then stepped aside. “Come on.”

His apartment smelled like coffee that had been made the old way—like someone actually cared if it tasted good.

No fancy syrup. No foam. No motivational quote on a mug.

Just coffee.

He poured it into two mismatched cups—one with a chipped rim, one that looked older than me—and we sat on the balcony with Buster curled between our feet like a living sandbag.

The sun was barely up. The city skyline looked like a row of tired teeth. Down below, cars moved like ants that didn’t know why they were hurrying.

Mr. Earl didn’t ask me how I was. Not right away.

He didn’t do that fake concerned tone people use when they’re really just fishing for gossip.

He just sipped his coffee and watched the light change.

Then, like he’d been waiting for the exact second my shoulders dropped half an inch, he said, “You still got that envelope?”

I froze. “What?”

“Don’t play dumb,” he said, eyes forward. “You still got it?”

My mouth opened, but nothing came out.

He nodded once, like he’d already seen the answer in my face.

“Alright,” he said quietly. “Here’s what we’re gonna do.”

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a thick black marker.

“You’re gonna write something on it.”

“What?” My voice cracked like I was fifteen.

He handed me the marker.

“Write: ‘NOT TODAY.’ Big letters.”

I stared at him.

“That’s cheesy,” I whispered.

“Life is cheesy,” he said. “Write it.”

My hand shook as I wrote on the envelope: NOT TODAY.

The marker squeaked like it was complaining.

Mr. Earl watched the letters dry, then took the envelope back and slid it into a kitchen drawer like it was nothing more than a takeout menu.

“You don’t throw it away,” he said. “Not yet.”

“Why?” I asked, throat tight.

“Because shame makes people lie,” he said. “And lies make people disappear. We ain’t doing that. We’re doing tomorrow.”

He took another sip of coffee.

“Now,” he said, “tell me one thing you’re doing today.”

I blinked. “I… I have a shift. Deliveries.”

“Generic deliveries,” he corrected. “No brand names. Don’t give the world free advertising.”

I almost laughed. It came out as something broken.

“And after that?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted.

Mr. Earl leaned back in his folding chair, joints popping like popcorn.

“You got two jobs today,” he said. “One, you go make your money. Two, you learn three names.”

“Three names?”

“Yep,” he said. “Three people in this building. Not usernames. Not apartment numbers. Names.”

“That’s impossible,” I said, automatically.

He glanced at me. “That’s your problem right there.”

He pointed with his coffee cup toward the hallway behind us.

“You think everything that matters is impossible. You live in a world that taught you to call basic human contact a miracle.”

He rubbed Buster’s head with his big, rough hand.

“Three names,” he repeated. “And you come back tonight, and you tell me one thing you saw today that didn’t make you hate being alive.”

My throat tightened again.

He didn’t say it dramatically. He didn’t say it like a therapist or a preacher.

He said it like a man who’d watched people fall apart in real time and learned the only way to stop it was to keep them talking.

“Okay,” I whispered.

Mr. Earl nodded. “Good. Now go walk that dog. He’s been holding his pee since Nixon.”

That day, the city felt the same—loud, expensive, indifferent.

The kind of day where the air itself feels like a bill.

I walked Buster around the block before work, and I realized something humiliating:

I didn’t know anyone.

Not really.

I’d been in that building for nine months and the most intimate conversation I’d had with a neighbor was “Sorry” in the elevator when my grocery bag ripped and a lime rolled under someone’s shoe.

That was my community.

A lime and an apology.

On my way back upstairs, I forced myself to slow down in the lobby.

A woman in scrubs was checking her mail, hair pulled back, eyes tired in a way that felt familiar.

I’d seen her a hundred times.

Never spoken.

My heart pounded like I was about to ask her to marry me.

“Hey,” I said, voice too loud.

She looked up, startled.

“I’m—” I swallowed. “I’m in 4B. I realized I don’t even know your name.”

Her face softened, just a fraction.

“Lena,” she said. “I’m 2D.”

“Lena,” I repeated, like it was sacred.

She smiled. “You okay?”

I almost lied. The old reflex.

But Mr. Earl’s marker ink felt fresh in my head.

“Honestly?” I said. “Not really. But I’m… working on it.”

Lena nodded like she understood more than she had time to explain.

“Good,” she said. “Keep working.”

She tucked her mail under her arm and walked out.

That was name number one.

I didn’t feel cured.

I felt… less invisible.

Later, as I was leaving for my shift, I saw a guy struggling with a stroller at the front steps. The stroller wheel caught on the lip of the sidewalk like the city itself was trying to trip him.

He looked like he hadn’t slept in weeks.

I stepped forward. “Need a hand?”

He blinked at me like kindness was suspicious.

Then he nodded once.

We lifted the stroller together. A tiny baby inside blinked up at the sky like it was brand new.

“Thanks,” the guy muttered.

“I’m in 4B,” I said. “I’m trying to learn names.”

He paused. “Darius. 3A.”

“Darius,” I said. “Nice to meet you.”

He looked down at the baby, then back at me.

“Nice,” he repeated, like the word tasted strange. “Yeah. Nice.”

Name number two.

By the time I got back that night, my feet ached and my head felt full of static.

I’d spent ten hours driving around the city delivering things people didn’t need urgently to people who acted like my time was a nuisance.

Every doorbell camera watched me like I was a suspect.

Every tip felt like a coin tossed at a performer.

And yet—somewhere between the traffic and the exhaustion—I kept seeing the same thing:

People weren’t mean because they were monsters.

They were mean because they were scared.

Scared of being broke. Scared of getting sick. Scared of falling behind. Scared of being forgotten.

And fear, when it has nowhere to go, comes out as cruelty.

When I got home, Mr. Earl was already on the balcony, pipe in hand, radio low.

I brought Buster to him at 6:30 PM like it was an appointment with my own future.

Mr. Earl didn’t look up. “Names.”

“Lena,” I said immediately. “2D. And Darius. 3A.”

Mr. Earl nodded. “That’s two. Who’s three?”

I hesitated.

He waited.

I exhaled. “I didn’t get three.”

He turned to look at me slowly, like a disappointed coach.

“Tomorrow,” he said. “You don’t miss three twice.”

Then he leaned back and said, “Now. One thing you saw today that didn’t make you hate being alive.”

I stared at the city.

My brain wanted to default to darkness. It was trained for it. It was efficient at it.

But then I remembered the baby’s face, the way it blinked at the sky like the sky had personally shown up for it.

“I helped a guy with a stroller,” I said quietly. “And his kid looked… happy. Like nothing bad existed.”

Mr. Earl’s eyes softened.

“There it is,” he said. “That’s your porch.”

The routine didn’t fix my bank balance.

It didn’t erase my debt.

It didn’t make the world less loud.

But it did something stranger and more dangerous.

It made me reachable.

Every morning at 6:30, I showed up.

Some days I talked. Some days I stared into my coffee like it held answers.

Mr. Earl didn’t push when I was quiet.

He just sat beside me like a lighthouse.

And slowly, without either of us naming it, the balcony stopped being Mr. Earl’s balcony.

It became… a place.

A real place. Not a digital one. Not one you could scroll past.

A place where time slowed down enough for people to notice each other.

One morning, Lena walked by with her scrubs and paused when she saw us.

“You two out here every day?” she asked.

“Every day,” Mr. Earl said.

She hesitated like she didn’t want to need anything.

Then she said, “My shift starts late today. Y’all got an extra cup?”

Mr. Earl didn’t even answer. He just stood up and went inside.

Ten minutes later, Lena was on the balcony with us, holding a mug and letting her shoulders drop.

The next day, Darius showed up with his baby in a carrier strapped to his chest.

“She sleeps better when there’s voices,” he said, almost embarrassed.

“Bring her over,” Mr. Earl said like it was obvious.

Then, one by one, the building started to reveal itself.

A retired woman named Mrs. Kline who baked too much because she couldn’t stand eating alone.

A quiet guy named Minh who worked nights and showed up at 6:30 AM because he was getting off his shift and didn’t want to walk into silence.

A teenager named Jay who pretended he wasn’t listening but stood in the doorway every morning like he was collecting proof that adults could still be decent.

And suddenly, the hallway didn’t feel like a tunnel.

It felt like a neighborhood.

Which is when the building management noticed.

It happened on a Friday.

We came out to the balcony and Mr. Earl’s folding chair was gone.

Not moved.

Gone.

In its place was a printed notice taped to the railing:

“COMMON AREA POLICY UPDATE: NO PERSONAL FURNITURE. NO GATHERINGS. PLEASE KEEP BALCONIES CLEAR.”

Lena read it out loud, eyebrows up.

Darius let out a short laugh that had no humor in it.

Mr. Earl didn’t say anything for a long time.

He just stared at the empty space where his chair had been, like someone had stolen a piece of his spine.

Then he said, softly, “They want us tired.”

Minh frowned. “What?”

Mr. Earl tapped the paper with one thick finger.

“They don’t want neighbors,” he said. “Neighbors talk. Neighbors compare notes. Neighbors ask questions.”

He looked at all of us.

“They want tenants,” he said. “Tenants pay. Tenants leave. Tenants don’t complain together.”

That sentence hit like a match.

Because we all knew it was true, even if none of us had said it out loud.

Lena crossed her arms. “So what do we do?”

Mr. Earl looked at me.

Not because I was the leader.

Because I was the one who almost disappeared.

And now, weirdly, I had the most to lose.

My throat went dry.

The old me would’ve shrugged and retreated. Avoid conflict. Don’t be noticed. Don’t be a problem.

But then I thought about that envelope in the drawer, with NOT TODAY written on it like a dare.

I thought about Darius carrying his baby just to hear voices.

I thought about Lena’s tired eyes softening over coffee.

And something in me hardened in a clean way.

Not anger.

Resolve.

“We don’t break rules,” I said slowly. “We don’t scream. We don’t threaten anybody. We just… show up.”

Mrs. Kline blinked. “Show up where?”

“In the lobby,” I said. “Or the courtyard. Or the sidewalk out front. Somewhere public where we’re allowed to exist.”

Jay scoffed like a teenager trying not to care. “They’ll call it loitering.”

Mr. Earl’s eyes flicked to him. “Boy, breathing is loitering to some people.”

Lena exhaled, half laugh, half sigh.

I kept going, voice steadier now. “We’ll keep it simple. Coffee at 6:30. Same time. Same faces. No furniture if that’s the rule. We’ll stand if we have to.”

Darius nodded slowly. “That’s kind of… wild.”

“Good,” Mr. Earl said. “Wild is alive.”

Minh looked nervous. “What if they… retaliate?”

The word hung there.

Because in America right now, “retaliate” can mean a lot of things.

It can mean a fee.

It can mean a warning.

It can mean your home suddenly feels conditional.

Mr. Earl’s voice softened. “That’s why we do it together.”

Lena looked at me, and I saw it—the same argument that lives in every comment section, every family dinner, every tired brain at 2 AM:

Why should I have to rely on strangers? Why should I have to fight for basic dignity? Why should it be this hard?

It’s a fair question.

It’s a painful question.

And it’s also the question that keeps people isolated, because the moment you admit you need others, you give up the illusion that you can control everything by yourself.

I swallowed.

“Because the alternative is disappearing,” I said quietly. “And I’m not doing that.”

Mr. Earl nodded once, like that was the only answer that mattered.

That weekend, I did something I hadn’t done in years.

I wrote.

Not a resume. Not an application. Not a cover letter pretending I was passionate about “fast-paced environments.”

I wrote a short post online.

No brands. No political rant. No villain named and shamed.

Just the truth.

I wrote about a seventy-something vet who believed in porches.

I wrote about coffee at 6:30 AM.

I wrote about how close I’d gotten to quitting life—not dramatically, not for attention, just quietly, like a tired person closing a door.

And I wrote about how a dog and an old man and a folding chair had pulled me back one morning at a time.

I hit post.

I didn’t expect anything.

But by Sunday night, my phone wouldn’t stop buzzing.

Strangers were sharing it with captions like:

“THIS.”

“I needed this.”

“Why am I crying?”

And then—because this is the internet—other people showed up too.

The ones who always do.

The ones who said things like:

“Maybe work harder.”

“Stop blaming the system.”

“Older generations had it harder.”

“You’re weak.”

“This is emotional manipulation.”

It was a mess.

It was also… a mirror.

Because the comments weren’t really about me.

They were about a country full of people who are exhausted and lonely and terrified, arguing over whether compassion is a luxury or a necessity.

Lena read some of them over my shoulder on Monday morning and shook her head.

“They’re mad that you didn’t die quietly,” she said.

Darius snorted. “They want a world where suffering is private, so they don’t have to feel guilty.”

Mr. Earl sipped his coffee and said, “Let them argue.”

Jay, leaning in the doorway like always, muttered, “Yeah, but arguing is all they do.”

Mr. Earl glanced at him.

“Then we do something else,” he said.

On Tuesday—one week after the night I almost vanished—we met in the courtyard at 6:30 AM.

No chairs.

No banner.

Just people.

The air was cold enough to sting. The sky looked undecided.

Mrs. Kline brought a thermos.

Minh brought paper cups.

Lena brought nothing but herself, which was the biggest thing she could’ve brought.

Darius showed up with the baby, who yawned like she owned the whole city.

And Mr. Earl—stubborn, upright, pipe unlit—stood there like a flag.

We didn’t chant.

We didn’t protest.

We didn’t even talk much at first.

We just existed in the same place at the same time, refusing to pretend we were alone.

A few residents walked past and stared.

Some smiled and kept going.

One guy rolled his eyes and muttered, “Unbelievable,” like friendship was an inconvenience.

A woman on the second floor cracked her window and watched us for a long time without moving.

Then, slowly, she raised a hand and waved.

Something in my chest loosened.

Mr. Earl leaned toward me, voice low.

“See that?” he said.

“What?”

“That,” he repeated, nodding at the window. “That’s the porch coming back.”

I swallowed.

Because it wasn’t a miracle.

It wasn’t a policy change.

It wasn’t some perfect solution.

It was smaller.

And somehow, that made it more powerful.

It meant it was something we could actually do.

Every day.

One morning at a time.

That night, I went back to my apartment and opened the drawer where Mr. Earl had put the envelope.

I stared at the words: NOT TODAY.

My hands shook.

Not with temptation.

With grief.

Grief for the version of me that thought disappearing was the only way to stop hurting.

I didn’t tear it up yet.

Not because I wanted it.

Because I wanted to remember how close I came, and how ordinary the rescue was.

No hero music.

No viral montage.

Just an old man with coffee and a dog who refused to let go.

I put the envelope back in the drawer and closed it.

Then I did something that would’ve seemed ridiculous a week ago.

I wrote three names on a sticky note and put it on my fridge:

Lena. Darius. Minh.

Below it, I added one more:

Earl.

And under that, I wrote:

6:30 AM.

Because here’s the part people argue about—the part that lights up comment sections like gasoline:

Some people will tell you loneliness is your fault.

Some people will tell you it’s society’s fault.

Some people will tell you to toughen up, grind harder, stop being dramatic, stop needing anybody.

And some people will tell you the opposite—that you’re a victim of everything and nothing matters.

But standing in that courtyard, watching a tired building slowly remember how to be human, I realized something that doesn’t fit neatly into anyone’s argument:

You can be responsible for your own life and still need people.

You can work hard and still be drowning.

You can hate the system and still love your neighbors.

You can be embarrassed to admit you’re not okay and still deserve to be seen.

The world is loud.

The bills are real.

The pressure is brutal.

But none of that changes one simple truth:

We are not built to survive alone in a box with a screen.

We are built for porches.

So if you’re reading this and you feel that familiar quiet closing in—if you feel like you’re becoming a ghost in your own life—don’t make a grand plan.

Don’t try to solve the whole world tonight.

Do tomorrow.

Find one name.

Drink one coffee with someone who doesn’t care what you post.

Stand in the same place at the same time as another human being, and let your nervous system remember what safety feels like.

And if you don’t have a porch?

Borrow ours.

6:30 AM.

Sharp.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta