Skip to Part 2 👇👇⏬⏬

The loudest scream I ever heard from my daughter was completely silent.

She didn’t throw a tantrum. She didn’t slam her bedroom door. She didn’t yell at me because I wouldn’t let her stay out late.

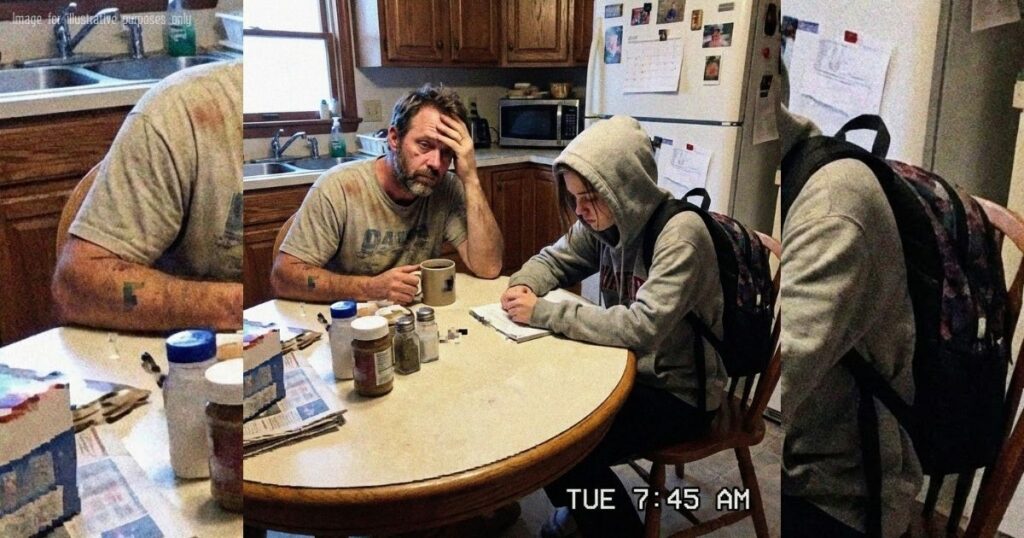

It happened on a Tuesday morning, right while I was pouring my coffee and checking the morning traffic on the news. She walked into the kitchen, her backpack hanging off one shoulder like it weighed a thousand pounds.

She looked at me, her eyes dry but incredibly tired, and said in a voice so calm it terrified me:

“Dad… can I go to a different school?”

I froze. The coffee mug hovered halfway to my mouth.

I asked her the standard parent questions. “Did something happen?” “No.” “Is it the grades? Is the math class too hard?” “No.” “Do you have friends to sit with at lunch?” She shrugged, looking at her shoes. “I don’t know.” “Is someone being mean to you? Is it a boy?”

Silence. Just a heavy, suffocating silence.

That night, I stared at the ceiling for hours. My wife was asleep, but my mind was racing. In America today, we hear the stories on the news. We see the tragedies. We assume it won’t happen to us until it does.

The next morning, I called my boss. “I’m taking a personal day.”

I didn’t tell my daughter. I drove to her middle school—a sprawling brick building in the suburbs that looked perfectly fine from the outside. I told the front office I needed to drop off some paperwork I’d forgotten. It was a lie.

I just wanted to see. I needed to see.

I stood in the hallway near the cafeteria doors during the passing period. The bell rang, and the chaos of American middle school exploded. Hundreds of kids flooding the halls, shouting, laughing, slamming lockers.

And then I saw her.

She wasn’t walking with a pack of friends. She wasn’t laughing at a TikTok on someone’s phone.

She was standing near the chain-link fence by the outdoor eating area. She was curled in on herself, holding a generic thermos like it was a shield. She was making herself small. Invisible.

A group of girls—the kind with perfect hair and expensive clothes—walked past her. They didn’t hit her. They didn’t shove her. It was subtler than that. They slowed down, whispered something, and laughed. One of them pulled out a smartphone, snapped a picture of my daughter standing there alone, and showed it to the group.

The explosion of laughter that followed hit me in the chest like a physical blow.

Then, a boy running past “accidentally” bumped her shoulder hard enough to spin her around. He spilled some of his energy drink down the sleeve of her hoodie. He didn’t stop. He just kept running, high-fiving his friend.

And my daughter? She didn’t yell. She didn’t chase him. She just pulled a napkin from her pocket and wiped her sleeve, biting her lip.

She looked like she was used to it. That was the part that broke me. She looked like this was just her Tuesday.

But what shattered my heart wasn’t the cruelty of the children. Kids can be mean; they are learning empathy.

What shattered me was the adult.

A teacher was standing ten feet away. He was wearing a lanyard, holding a clipboard, presumably on “lunch duty.”

He saw the girls laugh and take the photo (which is against school policy). He saw the boy body-check my daughter.

He looked at my daughter. He looked at the group. Then he looked at his watch, took a sip of his coffee, and turned his back.

He chose not to see.

It was easier to ignore it than to fill out an incident report. It was easier to pretend my daughter was invisible than to intervene.

I walked out of that school shaking with rage.

When I got home, I wrote an email to the administration. I detailed everything. I told them about the isolation. I told them what I saw—the cyberbullying, the physical intimidation, the “accidental” spills. I told them my daughter was fading away before my eyes.

The response I got from the Vice Principal was a masterpiece of corporate bureaucracy. It was cold, polite, and completely useless.

“Mr. Miller, we take these allegations seriously. We have a Zero Tolerance Policy for bullying. However, we haven’t received any formal reports from staff. Adolescence is a tricky time, and often these are just interpersonal conflicts. We will monitor the situation.”

“Monitor the situation.”

Translation: We will do nothing until it’s too late.

That evening, I sat on the edge of my daughter’s bed. She was pretending to read, but I knew she was just staring at the pages.

“Did you think about it, Dad?” she whispered.

I didn’t lecture her about resilience. I didn’t tell her to “toughen up” or that “the real world is hard.” She already knew the world was hard. She needed to know her father was soft for her.

“Yes, honey,” I said. “I thought about it. You are never going back there.”

She didn’t ask why. She didn’t ask about the logistics or the credits.

She just let out a long, shuddering breath. Her shoulders dropped three inches. It was the sound of a prisoner finally hearing the cell door unlock.

She goes to a different school now.

It’s an older building. It doesn’t have a brand-new football stadium or the latest tablets for every student. It’s a thirty-minute drive from our house, which costs us more in gas and time every morning.

But it’s different.

There, the Principal greets the kids by name at the door. There, the teachers don’t look at their phones during passing periods; they look at the students. There, she doesn’t have to shrink to survive.

Last week, I saw her laughing in the driveway with a new friend. It was the first time I’d seen her real smile in two years.

Parents, please listen to me.

A child does not ask to change schools on a whim. Changing schools is terrifying for a kid. It means being the “new kid,” eating alone, not knowing the rules.

If they ask to leave, it’s because the terror of the unknown is better than the torture of the known.

The deepest scars aren’t always left by the bullies who shove them in the hallway. The deepest scars are left by the silence of the adults who are paid to protect them.

We teach our kids to “See something, Say something.” But we, the adults, need to follow that rule too.

Don’t ignore the quiet signals. The drop in grades. The “stomach aches” on Monday mornings. The sudden hatred of the school bus. The silence.

Behind a simple “I don’t want to go today” might be fear, loneliness, and the crushing weight of rejection.

Give them the safe space to speak. And give yourself the courage to listen, and more importantly, to act.

Because sometimes, a child’s loudest cry for help sounds exactly like a whisper.

Don’t wait until you’re reading a police report or a hospital admission form. Look. Listen. React.

Your child’s peace of mind is worth more than their attendance record.

Part 2

The first thing my daughter did at the new school wasn’t smile.

It was flinch.

If you read Part 1, you already know I pulled her out. You know I chose the thirty-minute drive, the older building, the principal who stands at the door and says kids’ names like they matter.

What I didn’t tell you is this:

Moving her didn’t magically erase what was done to her.

It just changed the location of the wound.

Because trauma doesn’t clock out when the bell rings.

It rides home in the back seat. It sits at the dinner table. It waits in the hallway of your own house, quiet and patient, like it knows you’ll eventually walk past it.

And the first week at her new school, my daughter walked past it a hundred times a day.

On Wednesday—two days after her “silent scream” Tuesday—I drove her to the new campus before sunrise.

The parking lot lights were still on, casting those lonely pools of yellow over cracked asphalt. Kids stepped out of cars half-awake, backpacks bumping their hips, breath puffing in the cold.

Normal.

That was what I wanted: normal.

My daughter sat in the passenger seat with her hands folded so tightly in her lap her knuckles looked bleached.

“You don’t have to go in,” I said.

She nodded without looking at me.

“I know.”

Then she opened the door anyway.

That’s the thing about brave kids. They don’t do it with dramatic music playing behind them. They do it with their stomach in their throat and their heart punching their ribs and their face trying to pretend everything is fine.

She stepped onto the curb and froze.

Not because anyone was staring.

Because someone laughed.

It wasn’t even at her.

It was just… laughter.

Somewhere near the entrance, a boy said something to his friend, and the friend snorted.

My daughter’s shoulders jerked up to her ears like she’d been hit.

I watched her do the same thing she’d been doing at the old school: shrink.

Make herself smaller.

Take up less space in the world, as if space was something she had to earn.

I wanted to run after her.

I wanted to pick her up like she was five again and carry her inside and tell the whole building, This is a human being. Act like it.

But she’d made it clear the night before that she didn’t want a rescue scene.

“Please don’t come in,” she’d whispered through the crack of her bedroom door. “Not the first day. Just… let me try.”

So I stayed in the car, my hands wrapped around the steering wheel like it was the only solid thing in the universe, and I watched my daughter walk toward the doors.

A woman in a long coat stood by the entrance holding a clipboard.

The principal.

She smiled at a kid and said, “Morning, Marcus.” She elbow-bumped him like that was the most normal thing in the world.

Then she spotted my daughter—new kid, unfamiliar face, nervous energy radiating off her like heat.

And she did something that still makes my throat tighten when I think about it.

She didn’t call attention to her.

She didn’t loudly announce, “Welcome, new student!”

She simply stepped closer, lowered her voice, and said, “Hey. I’m glad you’re here.”

My daughter nodded. Her mouth did a weird little twitch, like her face had forgotten how to form expressions that weren’t defensive.

The principal pointed casually down the hall. “If you want, you can walk in with me. No pressure.”

And my daughter—my daughter who had been alone at a chain-link fence like it was a life sentence—fell into step beside her.

Not behind her.

Beside.

That tiny detail hit me harder than any speech ever could.

I drove home with my eyes burning and no idea whether to cry or breathe or scream.

So I did the only thing I could do: I made her lunch.

I know that sounds stupid.

But when your kid has been swallowed by a system that treats them like a problem to be managed, you start clinging to small acts of care like they’re oxygen.

I cut her sandwich into triangles like I used to when she was little.

I wrote a note and stared at it for five full minutes before deciding what to say.

Not “Be strong.”

Not “Ignore them.”

Not “Make friends.”

Just:

I see you. I’m proud of you. You don’t have to be perfect to be loved.

I folded it and put it in her lunch bag like it was armor.

That afternoon, she got in the car and shut the door carefully, like she was afraid a loud sound might break something.

“How was it?” I asked, trying to keep my voice neutral.

She stared straight ahead.

Then she said, “No one took a picture of me.”

It was delivered in the same tone some kids use to say, “We had pizza.”

Like it was a normal metric for whether a day was good.

My throat closed.

“That’s… good,” I managed.

She nodded.

And then she added, quieter: “The science teacher asked me to read a paragraph out loud.”

I felt my stomach tighten.

“And?”

“I said no.”

I waited for the rest. The part where she got punished. The part where the teacher rolled their eyes. The part where a kid mocked her.

Instead, she said, “And he said, ‘Okay. You can just listen today.’”

She said it like she didn’t quite believe it.

Like she was describing something supernatural.

I drove with both hands locked on the wheel, because I suddenly realized how low the bar had been at her old school.

Basic decency felt like a miracle.

That night, after she went to bed, my wife and I sat at the kitchen table in the same heavy silence that had been haunting our house for weeks.

My wife ran her fingers along the rim of her tea cup.

“I thought moving her would fix it,” she said.

“It will help,” I said.

“But it won’t erase it.”

She nodded and swallowed.

Then she asked the question that had been sitting between us like a third person.

“Are you going to let it go?”

I knew what she meant.

The old school.

The vice principal email.

The teacher on lunch duty who turned his back like my daughter’s humiliation was just background noise.

The “monitor the situation” line that made my skin crawl.

A part of me wanted to let it go.

We’d gotten her out. We’d saved her.

Why go back into the fire?

Then I remembered my daughter’s shoulders jerking at the sound of laughter.

I remembered the way she measured a good day by whether someone documented her pain for entertainment.

And I thought about all the kids still inside that building.

Kids without a dad who can take a personal day.

Kids whose parents can’t afford the gas money or don’t have flexible jobs.

Kids who go to sleep at night praying they wake up with the flu just to buy themselves one day of peace.

“No,” I said.

My wife closed her eyes like she already knew.

So I didn’t “let it go.”

I did what the school told me to do.

I “followed procedure.”

I requested a meeting.

I took off work again, because apparently protecting your kid in America is a part-time job you didn’t apply for.

They scheduled me two weeks out.

Two weeks.

Two weeks for a child’s safety. Two weeks for a family that had already been bleeding for two years.

On the day of the meeting, I sat in a beige office that smelled like printer toner and stale air freshener.

The vice principal sat across from me with a folder and a smile that didn’t reach his eyes.

A counselor sat beside him, hands folded, posture practiced.

The assistant principal I’d emailed wasn’t there.

“Scheduling conflict,” they said.

Of course.

The vice principal opened with the voice adults use when they want to sound empathetic but also want you to know you’re inconvenient.

“Mr. Miller, we understand you’ve had concerns.”

Concerns.

Like I was complaining about cafeteria food.

“I watched my daughter get photographed and laughed at,” I said. “I watched a boy slam into her and dump a drink on her and run away. I watched a staff member look at it and turn his back.”

The counselor’s face tightened slightly.

The vice principal nodded slowly, like he was listening.

“We take bullying very seriously,” he said, and I swear to you he sounded proud of the sentence, like repeating it was the same as doing something.

“Then why did no one do anything?” I asked.

He opened the folder and flipped a page.

“We have no record of reported incidents involving your daughter.”

I felt something in my chest go hot.

“No record,” I repeated. “Because the adults didn’t report it. That’s the problem.”

He lifted his hands in a calming gesture.

“Sometimes staff don’t perceive interactions the same way parents do.”

There it was.

The first hint of what this meeting really was.

Not accountability.

Damage control.

“So your argument,” I said, “is that my daughter wasn’t bullied because no one wrote it down.”

“I’m saying we need documentation,” he replied smoothly.

My wife, sitting beside me, spoke for the first time.

“My child asked to change schools,” she said, voice shaking. “Do you know how hard that is for a kid? Do you really think she did that because of ‘interpersonal conflict’?”

The counselor leaned forward.

“Adolescence is complicated,” she said softly. “Students sometimes struggle with social belonging.”

I stared at her.

That sentence might have been the most infuriating one of all, because it sounded gentle while erasing everything.

Social belonging.

Like my daughter was just having trouble finding her people.

Like she hadn’t been systematically isolated and humiliated.

Like there wasn’t a group chat somewhere with her picture in it, captions attached like knives.

“Here’s what I want,” I said, forcing my voice to stay steady. “I want you to investigate. I want you to pull camera footage. I want you to talk to the staff member on lunch duty. I want you to talk to the kids who were there.”

The vice principal nodded again.

“We can certainly look into general climate concerns,” he said.

General.

Climate.

Concerns.

He might as well have been talking about the thermostat.

“And,” he added, like this was a gift, “we can offer your daughter a mediated conversation with peers, should she return.”

My wife made a sound—half laugh, half sob.

“She’s not returning,” I said.

I expected them to at least pretend to care about that.

Instead, the vice principal’s shoulders relaxed, like hearing she wasn’t coming back made everything easier.

“I understand,” he said, and I saw it clearly then:

They weren’t worried about my daughter.

They were worried about paperwork.

About liability.

About the fact that a parent was sitting in their office naming specific failures.

And when people like that can’t deny what happened, they minimize it until it fits neatly into a file cabinet.

As the meeting ended, the counselor handed me a pamphlet about “resources for families navigating peer conflict.”

It was glossy.

It had stock photos of smiling children.

It felt like being handed a bandage after someone pushed you down the stairs.

I walked out of the building shaking—not with rage this time.

With something worse.

Clarity.

On the drive home, my wife stared out the window.

“They’re never going to admit it,” she said.

“No,” I replied. “They’re going to wait for the next kid.”

That night, I did something I’d been afraid to do, because once you do it, you can’t pretend you’re just a normal parent dealing with a normal problem.

I wrote an open letter.

Not naming the school.

Not naming staff.

Not naming kids.

I didn’t want revenge. I didn’t want a witch hunt. I didn’t want to risk anyone else’s safety.

I wanted the truth.

I wrote about my daughter’s quiet request.

I wrote about the chain-link fence.

I wrote about the adult who turned his back.

I wrote about the “no record of incidents” line, and how convenient it is for institutions to require documentation while creating an environment where documentation never happens.

Then I ended with a question—because questions are dangerous in a way accusations aren’t.

If a child is bullied in plain sight and the adults don’t write it down, did it happen?

I posted it to a local community forum under my own name.

My wife watched me hover over the button like it was a detonator.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“No,” I said.

And I clicked anyway.

The next morning, my phone was a living thing.

Notifications stacking like panic.

Comments. Messages. Shares.

Some were supportive.

Some were heartbroken.

Some were… furious.

It’s strange, the things people will defend.

Not children.

Not safety.

Not empathy.

But the illusion that everything is fine.

One comment said: Kids are mean. Your daughter needs thicker skin.

Another said: You’re why schools can’t discipline anymore. Parents like you blame teachers for everything.

A third said: Stop trying to ruin careers because your kid is sensitive.

Sensitive.

As if sensitivity is a character flaw instead of a human trait.

But the messages that really made my hands go cold were from parents.

Parents I didn’t know.

Parents whose kids went to that same school.

They didn’t comment publicly.

They messaged privately.

Because fear loves privacy.

Thank you for writing this. My son eats lunch in the bathroom.

My daughter cries every Sunday night. The school says they can’t do anything.

We reported it and they told us it was “mutual conflict.”

Mutual conflict.

That phrase showed up again and again, like it was scripted.

As if a kid being targeted by a group could be reframed as two equal sides having a disagreement.

As if saying “both” makes adults feel fair even when it makes kids feel abandoned.

One mother wrote, I’m scared to say anything because my son is finally invisible and I don’t want to make it worse.

I stared at that line for a long time.

Finally invisible.

What kind of world makes invisibility feel like safety?

By lunchtime, the open letter had reached people beyond our little community.

And with that came the next wave.

Strangers.

People who didn’t know my daughter. People who didn’t know me.

They didn’t ask questions.

They made judgments.

Some called me a hero.

Some called me a liar.

Some accused me of “making it political,” even though I never mentioned politics at all—only accountability and adult responsibility.

That’s when I learned another ugly truth:

In America right now, everything becomes a side.

If you say “protect kids,” someone hears “attack teachers.”

If you say “schools should intervene,” someone hears “parents are overreacting.”

If you say “bullying is serious,” someone hears “kids can’t be kids.”

So I did what I always do when the world starts screaming and I don’t know what to do with the noise.

I went to my daughter.

I found her on the couch with a blanket, doing homework.

Her brow was furrowed in concentration.

She looked… normal.

Tired, yes. Still guarded, yes.

But not disappearing.

I sat beside her slowly.

“Have you heard anything about what I posted?” I asked gently.

She didn’t look up.

“I heard kids at my old school were talking about it,” she said.

My stomach dropped.

“You did?”

She nodded.

“One girl messaged me,” she added, voice flat.

I waited, heart pounding.

“What did she say?”

My daughter finally looked at me.

Her eyes weren’t watery.

They were clear.

“She said, ‘Why are you trying to get everyone in trouble? It wasn’t that bad.’”

My hands curled into fists without permission.

“And what did you say?”

My daughter stared at her math worksheet.

“I didn’t respond,” she said.

Then, after a moment, she whispered: “But it was that bad.”

There it was.

The truth that doesn’t fit into an email from a vice principal.

The truth that doesn’t fit into a policy binder.

It was that bad.

And what’s worse—what should keep every adult awake at night—is that the kids who hurt her were already practicing the same skill the adults were modeling:

Denial. Minimizing. Pretending harm isn’t harm unless it leaves a bruise.

The next week, the school district held a public meeting.

I didn’t want to go.

Not because I was afraid to speak—rage makes you fearless—but because I was afraid of what speaking would cost my daughter.

My wife was the one who said, “If we don’t show up, we’re teaching her the same lesson they taught her. That silence is safer.”

So we went.

We sat in a cafeteria with folding chairs and bad acoustics.

The kind of room where big decisions about children’s lives are made under fluorescent lights.

Parents filled the seats.

Some looked exhausted.

Some looked angry.

Some looked like they were there to protect something—reputations, routines, comfort.

A few people recognized me.

I could feel their eyes on the back of my neck like heat.

When public comment started, a man stood up and said, “Teachers are doing their best. Parents need to stop blaming schools for everything.”

Applause broke out.

A woman stood and said, “Bullying has always existed. We can’t bubble wrap kids.”

More applause.

Then another parent stood.

A mother with shaking hands.

“I’m not here to blame teachers,” she said. “I’m here because my child told me he wants to disappear.”

The room shifted.

You could feel it—like someone had opened a window.

She continued, voice cracking. “And when I told the school, they asked if he was sure he wasn’t ‘misreading’ social cues.”

Silence.

I watched people’s faces.

Some softened.

Some hardened.

Some stared straight ahead, refusing to let the truth land.

Because once it lands, you have to do something with it.

And doing something is expensive.

Time. Money. Energy. Conflict.

It’s easier to clap for “toughness” than to fund supervision in hallways.

It’s easier to say “kids will be kids” than to admit we’ve built a culture where kids treat cruelty like entertainment.

When my name was called, my legs felt like they belonged to someone else.

I walked to the microphone and looked out at a room full of parents who all thought they were good people.

Because most of them were.

That’s the scariest part.

Harm doesn’t always come from monsters.

Sometimes it comes from normal adults protecting normal comfort.

“I’m not here to punish kids,” I began. “And I’m not here to attack teachers. I know many teachers are drowning. I know classrooms are hard. I know staff are stretched.”

A few heads nodded. A few shoulders relaxed.

Then I said, “But there is a difference between being stretched thin and turning your back.”

The room went still.

I described what I saw—without names, without drama, just facts.

A picture taken.

A shoulder checked.

A staff member looking.

A staff member turning away.

Then I said the sentence I’d been carrying like a stone:

“My daughter learned that the people paid to protect her would rather protect their own peace.”

A man in the back muttered something. I didn’t look.

I added, “We tell kids to speak up. We tell them to report. But reporting is meaningless if the adults don’t document. And documentation is meaningless if it’s only used to protect institutions instead of children.”

I paused.

My voice shook, but I kept going.

“If you’re angry at me for posting, ask yourself why. Is it because you think I lied? Or is it because you’re terrified it’s true and you don’t want your child’s school to look bad?”

That line did what I knew it would do.

It split the room.

Some people nodded.

Some people scowled.

Because that’s the controversial truth nobody wants to say out loud:

A lot of adults would rather have a “good school” on paper than a safe school in reality.

When I finished, I walked back to my seat and sat down beside my wife.

My hands were trembling.

My wife squeezed my knee under the table.

And then something happened that I didn’t expect.

A teacher approached us during the break.

Not one of my daughter’s teachers—someone I didn’t recognize.

She was in her thirties, hair pulled back, face tired in a way that went deeper than sleep.

“I read your letter,” she said quietly.

I braced myself for anger.

Instead, she said, “I’m sorry.”

I blinked.

She looked down at her hands.

“People don’t want to hear this,” she continued. “But some of us are burned out and afraid. Afraid of complaints, afraid of confrontation, afraid of doing the wrong thing. And sometimes… we freeze.”

I thought of the lunch duty teacher with the coffee.

My jaw tightened.

“That doesn’t make it okay,” I said.

“I know,” she replied. And her eyes filled with tears that she wiped away fast, like even emotion was another thing she didn’t have time for. “I’m telling you because I need you to know something else too.”

I waited.

She leaned closer.

“There are staff who have reported things,” she whispered. “And they get told to ‘handle it in the classroom’ or ‘don’t escalate.’”

My stomach dropped.

“Why?” my wife asked.

The teacher’s mouth tightened.

“Because escalation creates records,” she said. “And records create problems.”

Then she stepped back like she’d said too much and walked away.

I sat there staring at the empty space she left behind.

Records create problems.

Not harm.

Not trauma.

Not kids begging their parents to change schools.

Records.

That’s what the system feared.

That night, my wife and I lay in bed in the dark, not touching, not because we didn’t love each other, but because we were both exhausted in our own private ways.

My phone buzzed again and again.

More messages.

Some were supportive.

Some were cruel.

One said, If you cared so much, you should have taught your kid to fight back.

Another said, This is why kids are soft now.

Soft.

Like softness is the enemy.

As if the goal of childhood is to become harder instead of kinder.

I turned the phone face down.

In the dark, my wife said, “Are we doing the right thing?”

I stared at the ceiling.

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “But I know what the wrong thing looks like.”

“What?”

I swallowed.

“It looks like a teacher turning his back.”

The next morning, something small happened that changed everything.

My daughter came downstairs wearing a different hoodie.

Not the oversized one she’d been hiding in for years.

This one fit her.

It was still plain. Still safe.

But it fit.

She poured cereal and sat at the table.

And then she said, like she was talking about homework:

“Dad?”

“Yes?”

“Can you stop posting about it?”

My heart stopped.

I leaned forward.

“Are kids bothering you?”

She shook her head.

“No. Not here.”

“Then why?”

She stared at her cereal, spoon moving in slow circles.

“Because,” she said carefully, “I don’t want to be the story.”

My throat tightened.

“I don’t want to be… the bullied girl everyone talks about,” she continued. “I want to be… me.”

I sat back like someone had gently pushed my chest.

I realized then that even good intentions can become another kind of pressure.

I’d been fighting for her.

But I might also be making her carry the weight of the fight.

I nodded slowly.

“Okay,” I said. “I hear you.”

She looked up, surprised.

“You’re not mad?”

“No,” I said. “I’m proud you told me.”

She exhaled, relief softening her face.

Then she added, quieter: “But… you can keep helping. Just… don’t make it about me.”

That’s the line I want every parent to hear.

Your kid can be hurting and still want privacy.

They can need protection and still want control over their own narrative.

So I changed what I did.

I stopped posting personal details.

I stopped writing as “my daughter’s dad.”

And I started showing up as a community member.

I connected parents with each other privately.

I encouraged people to document—dates, times, screenshots—without turning it into a public circus.

I helped one mother draft an email that didn’t sound emotional, because I’d learned the hard way that institutions love to dismiss emotion as “hysteria.”

I learned which phrases got attention and which got auto-replies.

Not because I wanted to play games.

Because the system forced us to.

And yes—before anyone asks—I considered taking legal action.

Of course I did.

I’m a father. I would walk through fire.

But I’m not here to give anyone legal advice, and I’m not here to sell revenge fantasies.

I’m here to tell you what happened next in a way that might save someone else’s kid.

Two months into the new school, my daughter brought home a permission slip for a club.

A club.

She slid it across the counter like it was nothing, but her eyes flicked to my face like she was bracing for disappointment.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“A writing club,” she said quickly. “It’s stupid.”

“It doesn’t sound stupid,” I said, forcing my voice to stay casual even as my heart tried to burst.

She shrugged.

“It’s just… after school.”

I signed it.

She grabbed the paper and left the room before I could say something embarrassing like “This is the happiest day of my life.”

Later that week, I picked her up after the club.

Kids spilled out of the building laughing, holding notebooks, talking too loud.

My daughter walked out with two girls beside her.

They weren’t “perfect hair and expensive clothes” girls.

They were normal kids with messy ponytails and braces and awkward limbs.

One of them said something and my daughter laughed.

Not the small polite laugh she’d been practicing.

A real laugh.

It startled her.

I saw it on her face—this momentary shock, like her body didn’t recognize its own joy.

Then she saw me and her laughter folded itself away instinctively.

But it came back.

A smaller version, but still real.

In the car, I kept my eyes on the road like that would keep me from crying.

“How was it?” I asked.

She hesitated.

Then she said, “Good.”

A pause.

Then, like she was testing the words:

“Really good.”

I swallowed hard.

“What did you do?”

She stared out the window.

“We wrote about a time we felt invisible,” she said.

My hands tightened on the wheel.

“And?”

She shrugged, but her voice changed.

“It was weird,” she admitted. “Because… I wasn’t the only one.”

There it was.

The other truth adults forget:

Pain isolates you by convincing you you’re alone.

But when kids finally find safe rooms—clubs, small groups, one decent teacher—they learn that silence wasn’t proof they were the problem.

It was proof they were trapped.

That night, my daughter left her notebook on the kitchen table.

I didn’t open it.

I wanted to.

God, I wanted to.

But I didn’t.

Because healing also means giving them dignity.

Instead, I made dinner.

And when she sat down to eat, she told us something that made the air leave my lungs.

“There’s a girl in my grade,” she said. “She eats alone.”

My wife’s eyes met mine.

My daughter kept talking like she was reciting a fact.

“Some kids call her weird.”

I waited, afraid of what would come next.

Then my daughter said, “Today I asked if she wanted to sit with us.”

My voice came out rough.

“And what did she say?”

“She looked like she thought it was a prank,” my daughter replied, eyes on her plate. “But then she sat.”

I stared at my child.

The same child who couldn’t even speak when she was being humiliated.

The same child who had been trained to disappear.

Now reaching out.

My wife put her hand over her mouth.

My daughter shrugged again, trying to act like it was nothing.

“It wasn’t a big deal,” she said.

But it was.

It was everything.

Because it meant the old school didn’t get to define her.

It meant pain didn’t make her cruel.

It meant the story didn’t end with her becoming hardened and numb and cynical, like some commenters online think is the goal.

It meant she was still soft.

And softness—real softness—isn’t weakness.

It’s courage.

A few weeks later, I got another email from the old school.

A generic district email.

A survey.

They wanted feedback on “school climate.”

I stared at it for a long time.

There was a part of me that wanted to delete it and never think about them again.

Then I thought about the teacher who whispered, “Records create problems.”

So I filled out the survey.

I didn’t curse.

I didn’t threaten.

I didn’t name names.

I wrote the truth in calm sentences that couldn’t be dismissed as “emotional.”

I wrote:

A policy is not protection if staff are trained—directly or indirectly—to minimize incidents to avoid documentation.

I hit submit.

And then I closed my laptop.

Because the fight, I’ve learned, isn’t always loud.

Sometimes it’s just refusing to let adults hide behind paperwork.

Now here’s where I’m going to say something that will probably make people argue in the comments.

And that’s fine.

Because maybe we should argue about it.

Maybe that’s how we finally stop treating this like a normal part of growing up.

Ready?

I think a lot of adults secretly believe bullying is useful.

They won’t say it like that.

They’ll say things like:

“It builds character.”

“It prepares them for the real world.”

“Kids need to learn to handle it.”

But strip away the pretty words and what they’re saying is:

Some children’s pain is acceptable as long as it toughens them up.

And I’m asking you—honestly—what kind of society requires children to be broken to be “prepared”?

We don’t tell adults to tolerate harassment at work to build resilience.

We don’t tell wives to “toughen up” when they’re being disrespected in public.

We don’t tell soldiers with trauma to “just get over it.”

But we tell kids—children with developing brains and fragile identities—that humiliation is a rite of passage.

And we call it normal.

No.

It’s familiar.

It’s common.

But it should not be normal.

Another thing people don’t want to admit:

When adults ignore bullying, they’re not being neutral.

They’re choosing a side.

They’re siding with the loudest, the cruelest, the most socially powerful kids—because those kids are easier to appease than the quiet one sitting by the fence.

Silence isn’t harmless.

Silence is a decision.

And if you’re reading this as a parent, here’s the part I hope goes viral—not because it’s dramatic, but because it’s true:

Your child might never tell you the worst of it.

Not because it’s not happening.

But because they’ve learned that adults don’t want the truth.

Adults want the version that’s easy to fix.

A kid will tell you “I don’t like school.”

They won’t tell you, “I’m practicing ways to disappear.”

They’ll say “My stomach hurts.”

They won’t say, “I’d rather be sick than be seen.”

They’ll whisper, “Can I go to a different school?”

And if you’re lucky—if you’re unbelievably lucky—you’ll hear the scream inside that whisper before the world forces it out in a way you can’t undo.

My daughter is doing better.

Not because the world suddenly became kind.

But because one building had adults who actually looked at kids.

Who said names at the door.

Who let a kid say “no” without punishment.

Who understood that safety isn’t a poster on a wall.

Safety is attention.

It’s presence.

It’s courage.

And I’m going to leave you with the question that keeps me up at night, the one that will probably split people down the middle:

If your child asked to leave a school—quietly, without drama—would you assume they’re being “sensitive”?

Or would you assume they’re being honest?

Because now that I’ve seen what I’ve seen, I can’t unsee it.

And I can’t stop thinking about the kids still standing by that fence, holding their lunch like a shield, learning the same lesson my daughter learned:

That their pain is invisible as long as it’s convenient.

So argue with me if you want.

Tell me kids need thicker skin.

Tell me parents are overreacting.

Tell me schools are trying their best.

Maybe all of that is true.

But answer this—really answer it:

If it were your child shrinking to survive…

Would you still call it “just adolescence”?

Or would you call it what it is?

A quiet emergency.

And the adults in the room deciding whether it matters.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta