Part 1 – The Dumpster at Dawn

At 9:12 a.m., in a municipal courtroom that smells like old paper and nerves, I rose to argue a public-nuisance case—and realized the man we were trying to crush was the veteran who once pulled me out of a dumpster.

Before the judge could see my hands shake, every memory I’d buried under new names and framed diplomas came roaring back with motor oil, burnt coffee, and a voice asking, Are you safe, kid? Come inside.

I knew him before I knew safety had a shape.

Cole Walker, sleeves rolled, forearms scored with old sun, a chipped white mug steaming in January air.

The first time we met, I was fourteen and smaller than the black trash bags I hid behind.

I’d been sleeping behind his shop because the back alley was brighter than the place I’d run from.

He opened the door at 4:59 a.m. like a ritual he’d learned in another life.

He did not ask why a kid was curled between cardboard and a busted pallet; he asked if I was safe.

I said nothing and nodded like a liar.

He handed me half a breakfast burrito and the chipped mug, the heat briefly convincing my fingers they belonged to a body.

“You know how to hold a wrench?” he asked without looking up.

I shook my head and he grunted, which I later learned was Cole for You will.

There were rules, posted on a grease-smudged clipboard by the punch clock.

Go to school, show up on time, tell the truth even when it’s the hardest thing you do all week.

He didn’t say family; he set out two plates and let me discover the word.

If I swept the floor straight and didn’t mouth off, the side door “accidentally” stayed unlocked.

On Sundays he cooked like it was a mission.

We ate at a folding table while the space heater rattled, and he quizzed me on vocabulary words between bolts and brake pads.

He never once called the cops on me.

He did sit next to me at a clinic, hands folded around that chipped mug, while a nurse checked the bruises I said were from “falling.”

Years later, I told people I made it out because I worked hard.

The truer thing is I made it out because someone opened a door before I earned it.

I learned to hold a wrench and then a pen and then a closing argument.

I learned the sound a dog tag makes when it taps a coffee mug, metal on ceramic, time on time.

Between then and now, I sanded my rough edges with degrees and the right phrases.

I practiced sounding like people who never had to wonder where they’d sleep.

I joined a firm that believed in neat stories and clean shoes.

I stopped visiting the shop and told myself the city needed lawyers who knew both sides of the tracks.

Which is how I ended up assigned to a case labeled “land-use compliance” instead of what it is.

Neighbors complaining about noise and perception, a shop accused of “degrading the area,” a life’s work reduced to a bullet point.

I scanned the file last night and didn’t see his name, just an address I skimmed.

This morning I stood to speak and finally looked at the defendant’s table.

Cole, in a clean work shirt and those boots that never learned to shine.

Dog tag under the collar, the chain glinting when he breathed in slow.

He did not seem surprised to see a man in a suit where a boy used to be.

He did tilt his head the way he did when a bolt wouldn’t budge.

“Counselor?” the judge prompted, and my voice arrived late to my body.

“Ready, Your Honor,” I said, and hated the distance in the word.

Across the aisle, the other side started with photos and numbers.

Two noise complaints, three 311 calls, the kind of math that ignores what it can’t count.

I stared at my legal pad and saw a grocery list from 2007 in Cole’s handwriting.

Beans, tortillas, printer paper, work gloves—things you buy when you expect someone to stay.

Jenny, my paralegal, watched me from the second row with her you-better-choose eyes.

She knows I come from a place that doesn’t exist on resumes.

I rose for a procedural point and asked for time to clarify a conflict.

The courtroom murmured like rain on tin.

The opposing attorney smiled a kind, sharp smile.

“Conflict, Counselor? Or conscience?” she said, gentle enough to sting.

I looked at Cole and felt the floor tilt.

In my head I heard the heater rattling, the fork scraping a paper plate, his voice saying, Try again.

“Your Honor,” I said, “I need to disclose—”

The other attorney cut in, filing a motion and sliding a thin folder onto the rail.

Inside were records I thought I’d outrun.

A juvenile intake form, a shelter note, a name I haven’t answered to in years.

“Isn’t it true,” she asked, soft as a match, “that you previously resided at the defendant’s address under another name?”

The room leaned closer, hungry for a story that wasn’t in the exhibits.

Jenny’s hand found the edge of the bench and stilled there.

My mouth was a locked drawer and the key was somewhere under a pile of old wrenches.

“Counselor?” the judge said again, patience thinning into procedure.

My first instinct was to run outside and breathe in winter like a cure.

Cole didn’t move.

He just let the dog tag tap the mug, one small sound, like a lighthouse in a fog I made myself.

The attorney folded her hands.

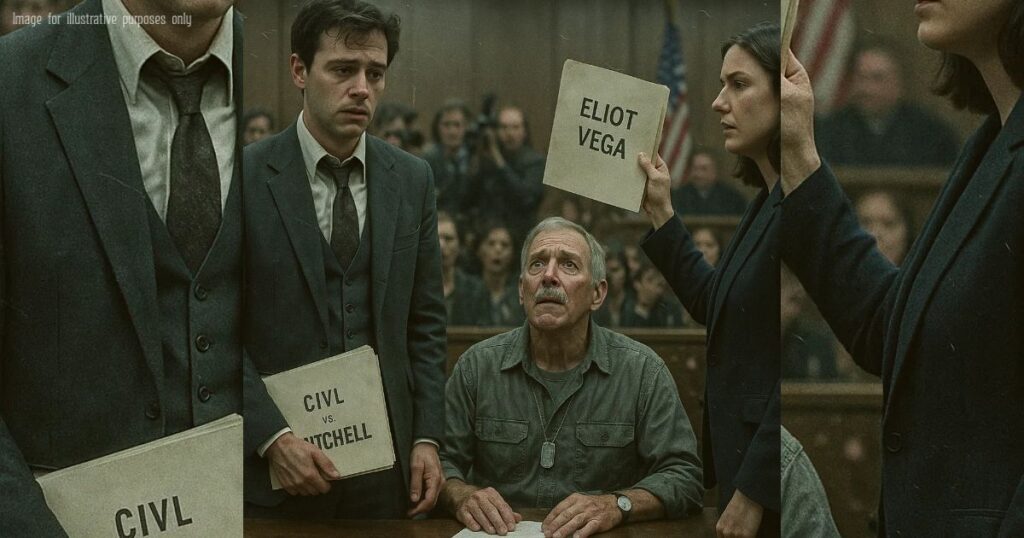

“Shall we do this the easy way, Mr. Reyes—” she paused, eyes on the file— “or shall we address you as Eliot Vega?”

The gallery went silent in that particular American way, when strangers smell confession.

Cole lifted his head and found me the way you find a star you already know.

“Son?” he said, not loud, not weak, just the exact weight of truth I’d been dodging.

Part 2 – Coffee, Grease, and Second Chances

The judge waited for my answer while the clock ticked in a way that made every second sound like a verdict. I felt the old name rise like smoke from a place I swore I’d sealed, and I decided to stop pretending I didn’t smell it.

“Yes, Your Honor,” I said, forcing my voice into daylight. “I previously resided at the address of the defendant’s shop as a minor, under a different legal name, and I am requesting permission to withdraw due to a conflict that became apparent only this morning.”

The judge studied me over the top of her glasses for a long beat that took up the whole room. Then she nodded once, a small thing that felt like permission to breathe.

“Motion to withdraw is granted,” she said, turning to the clerk without looking away from me. “We’ll reset the schedule for a status conference in forty-eight hours, and I expect replacement counsel to be ready to proceed.”

The opposing attorney kept her smile polite, which is another way to say sharp. “Understood, Your Honor,” she answered, folding the thin folder as if it were laundry and not my childhood.

I packed my briefcase with the neatness I used as a shield and walked out before my legs decided to stand on principle and collapse. In the hallway, the air felt thinner, as if the building were trying to fit the entire city’s arguments inside it.

Cole was already there, leaning against a wall like it was a chore he intended to do properly. He held that chipped mug in both hands even though there was no coffee in it, just habit and the sound a dog tag makes when it touches ceramic.

“You okay, kid?” he asked, voice low enough that the word didn’t carry, only the warmth did. He added a second sentence like a bandage, careful and plain. “You don’t owe me an answer.”

“I’m not a kid,” I said, out of reflex before I could help it. Then I swallowed the pride and tried again. “Thank you for asking, and I’m sorry you had to find out like that.”

“Names change,” he said, tapping the mug with the ring of his finger so the tag answered back. “People, not so much, and sometimes that’s good.”

Jenny hovered close enough to hear but far enough to leave me one last inch of dignity. She looked at Cole, then me, then the courtroom doors like she was measuring the distance between bad decisions and better ones.

“You’re going to tell your firm,” she said gently, the words shaped like a suggestion but balanced like an order. “And you’re going to decide which side of the table you want to live on.”

“Already decided,” I said, though I hadn’t until I heard the sentence out loud. “I’m resigning from the city’s matter, and I want to represent Mr. Walker, if he’ll have me.”

Cole’s face didn’t crack into anything dramatic; he was a man who saved big movements for engines and small ones for people. He set the mug on the windowsill like a paperweight for the next five minutes and looked me in the eyes the way you do when you’re torqueing truth.

“If you do this,” he said, “you do it by the book, even if the book is heavy. You don’t use anything you learned on the other side except the part where you remembered who you are.”

“By the book,” I promised, and meant the law school version and the Sunday-night version taped above the punch clock.

I called my managing partner and got put on hold long enough to memorize the pattern in the lobby’s tile. When he picked up, I explained the conflict and my intent to withdraw from the matter fully and permanently, while observing every ethical wall in the known universe.

He congratulated me on my professionalism like it was Christmas, then reminded me that our clients value appearances almost as much as outcomes. He did not say “choose us or him,” but sentences don’t need all their words to be understood.

“Thank you,” I said, and ended the call with the kind of courtesy that feels like bleeding slowly inside expensive fabric. Jenny watched me put the phone away and nodded like she was checking torque on a bolt.

“Okay,” she said. “We’ll draft the notice of appearance for Mr. Walker and put a memo in the file documenting the screen from anything you touched on the city side. I’ll also reach out to the clerk to confirm the new status conference.”

Cole lifted the mug and forgot it was empty, then smiled at himself for the habit. “Before all that,” he said, “you should eat something that isn’t a decision.”

We crossed the street to a corner place that smells like eggs and quiet arguments. Cole ordered for both of us like he always did when I was too proud to admit I didn’t know what I wanted and too hungry to leave with nothing.

“I owe you an apology,” I said, when the plates landed and the steam pretended to be courage. “At my law school graduation, I called you a ‘family friend’ to people who weren’t even friends, and I never corrected it.”

“You were busy becoming someone you thought they’d listen to,” he said, breaking toast with the carefulness of someone who’d done it in mess halls and borrowed kitchens. “That’s not a crime, that’s a season.”

“I don’t want those seasons anymore,” I said, and meant it, even if I didn’t know how to mean it every day for the rest of my life. “I want to do this right.”

He nodded once, the way he did when an engine finally idled true. “Then we’ll start where we always start,” he said. “We go back to the shop.”

The walk to the shop took us past a new café with polished wood and plants that looked like they preferred other neighborhoods. On a corkboard was a flyer asking the city to “clean up the block,” and I read the list of complaints the way you read a weather report that forgot to mention people.

At Homefront Repair, the bay doors were half open like an eyelid after a hard night. A yellow paper hung under the latch, taped with wide, confident strokes that didn’t care how the day would go for anyone else.

“Notice of Violation,” I read, the language neat and bloodless. “Pending administrative hearing, possible temporary closure for inspection, alleged noncompliance with noise and occupancy standards.”

Cole took the notice off, smoothed it on the workbench, and set the mug on one corner to keep it from curling back into threat. He reached for a pen, and the dog tag clicked in the small way it does when the world tries to wobble us.

“These come and go,” he said, which is what you say when you’ve lived long enough to see waves and refuse to call each one a flood. “We keep the place clean, we keep the kids safer than the street, and we show up on time.”

I looked around and saw my entire adolescence hanging from hooks: an army jacket that wasn’t a costume, a whiteboard of algebra I pretended to hate and secretly memorized, a stack of library paperbacks still smelling like other people’s houses. The rules clipboard was there, grease-smudged and unembarrassed.

“Go to school,” I read, hearing the boy who used to mouth the words to make them true. “Show up on time. Tell the truth, even when it’s the hardest thing you do all week.”

“Add one,” Cole said, handing me the pen like a key to a door I’d left locked too long. “Ask for help before midnight.”

“Even lawyers?” I asked, and he smiled into his coffee that wasn’t there.

“Especially lawyers,” he said, and the shop warmed by a degree no thermostat could measure.

Jenny arrived with a legal pad and a look that said she’d run the last block because ethics doesn’t get Ubered. She spread out a to-do list like a field map, and for the first time since the morning I felt the ground want me.

“We’ll need folks willing to testify about community benefit,” she said, ticking boxes as if punctuation could hold the roof on. “Not character sermons, just concrete acts—classes taught, scooters fixed, job placements, referrals to services.”

“I can call Ms. Alvarez from the school,” I said, thinking in straight lines for the first time all day. “And Mr. Hurley with the mobility repairs, and the coordinator at the clinic who knows our Sunday nights are loud mostly because of laughter.”

“We also prep for optics,” Jenny said, not apologizing for the word because someone had to say it. “No late-night engines this week, bay doors closed at eight, safety posters up where cameras can find them.”

Cole nodded, already wiping a clean rag across a clean toolbox because you don’t only tidy for inspectors. You also tidy for the kid who might try your doorknob in the dark and decide to live.

While we worked, a neighbor stopped at the threshold with her dog, hovering the way people do when they want to say something kind but don’t want to join a fight. She thanked Cole for fixing her dad’s walker last winter and left a pie on the counter without waiting for change.

“That counts,” Jenny said, writing pie in the margin as if sugar could be an exhibit. “Sometimes kindness is a measurable outcome.”

The shop phone rang and the sound went through me like a drill hitting a stud. Cole answered, listened, and covered the receiver with his palm.

“Inspector’s moving the administrative hearing up to Friday at nine,” he said, eyes on me like he was spotting a lifter. “Says they’ve had a spike in complaints and want to be efficient.”

“Friday,” I repeated, as the clock in my head started to spin the way it does when deadlines and destinies share a calendar. “We’ll be ready, and we’ll be respectful, and we’ll keep this about the facts.”

Cole’s dog tag tapped the mug, and the sound was quieter than fear but louder than quitting. He looked at me the way you look at the person you’re going to hand the wrench to when your knuckles are done.

“Are you safe, kid?” he asked, old words fitting a new hour in a way that made me want to stand up straighter. “Come inside, and let’s get to work.”

We turned back to the bench, three pens moving in the same direction like we were drafting blueprints for something sturdier than walls. Outside, the afternoon slid toward a kind of dark I remembered and didn’t fear.

The bay door rattled once as wind found the seam, and the notice on the counter tried to curl again before the mug told it no. Somewhere across town, a printer spat out another agenda, another hearing, another chance to argue that home can look like a shop and family can sound like a wrench.

The phone rang again, a new voice asking if we were hiring, a voice that cracked on the word “we.” I looked at Cole, and he handed me the receiver as if the handle were the first tool in a set we were going to share.

Part 3 – The Ghosts We Don’t Report

We built our case with chipped mugs and receipts, not slogans. The plan was simple and heavy: gather proof of what the shop actually does, prepare witnesses who speak in plain nouns, and keep our tone respectful even when the internet tried to turn people into caricatures.

Cole kept working while we listed names. He wiped tools that didn’t need wiping, checked cords that didn’t need checking, and breathed through a rhythm I recognized from the years when sleep bargained with old noise. The dog tag tapped the cup every few minutes like a metronome for courage.

Ms. Alvarez from the middle school arrived in a jacket that had graded a thousand papers. She brought a binder with attendance charts for students who’d improved after Saturday classes in our back bay. She didn’t come to praise us; she came to explain that safety looks like a place where a twelve-year-old can ask about fractions without feeling like a problem.

Mr. Hurley rolled in with a walker that squeaked in a friendly way. He told us he couldn’t testify long, but he wanted the record to show Cole had repaired a neighbor’s wheelchair in the rain and refused payment except for a story about the man’s garden. Jenny took notes like she was catching falling plates and stacking them into something that could stand.

DeShawn, now an HVAC tech, showed up still in his uniform. He was the first kid I remembered tutoring under the hum of the space heater, both of us pretending we only liked verbs that turned bolts. He had a job list from the union apprenticeship program, and he circled the names of people he’d recommended after Cole taught them how to arrive.

“Facts first,” Jenny reminded each person gently. “Short sentences, dates if you have them, and what you saw with your own eyes.”

Cole made a pot of coffee and forgot it on the warmer until it tasted like a lesson. He poured it anyway and smiled at our faces as if bitterness could be a joke we were in on together. By noon the counter looked like a modest courtroom: affidavits, photographs, repair tickets, clinic referral cards, and a pie someone decided was legally relevant.

In the quiet between doorbells, I found the little green notebook he kept near the register. It wasn’t secrets; Cole didn’t keep those if he could help it. It was headings written in a tidy block print: After-Action. Inventory. Reminders. Souls.

Under After-Action he’d written lines that sounded like training and prayer. Secure perimeter: check doors, lights, kids’ bus routes. Feed team: dinner items, dietary notes, birthdays. Account for souls: who left angry, who left lighter, who didn’t show and needs a call.

I closed the notebook because reading it felt like stepping into a chapel. Cole shrugged when he saw my face and said he learned long ago you don’t measure a night by how many tasks got done but by how many people felt less alone leaving than they did coming in.

By midafternoon, the first storm rolled in on a screen. A social account with a lot of followers posted a stitched video of the shop: bikes revving past midnight, a half-second of a raised voice during a summer argument, Cole gesturing toward a door spliced to make it look like he was telling someone to get out. The caption asked a question that pretended to be neutral and was anything but.

Jenny clicked the volume off and reminded us not to read the comments. We read the comments anyway because we are human and because the mind goes where it hurts. People argued about noise and neighborhoods and what kind of men drink coffee from chipped mugs, as if ceramic could prophecize.

“We answer with proof,” I said, making my voice slow because fast voices spill. “Not with counterattacks. We show schedules, sign-in sheets, noise logs, and we bring in people the camera didn’t.” Cole nodded and moved the mug from one pile to another as if truth weighed more than paper.

A knock at the door revealed a teenager with a backpack and a look that wanted to be older. He asked about the job we maybe had, the one that required sweeping and listening. Cole didn’t look at me when he answered; he kept his eyes on the kid like you keep a light on a path. “Application’s simple,” he said. “Show up tomorrow at seven, and tell the truth even if it tastes like metal.”

The boy nodded in that way where nodding is a bridge you build while you step on it. He left his contact on a form Jenny drafted on the spot and promised a parent would call, and I believed him because his voice cracked on the word parent in a way that told me he wanted the call to exist.

At four, Maya came by on her break from the clinic with a stack of pamphlets about after-school resources. She spoke softly and carried a calendar. “If the hearing goes our way,” she said, “I’d like to pilot a once-a-month health night here. Blood pressure checks, flu shots, referrals.” Cole said yes before she finished because saying yes to help was one of the ways he kept breathing right.

A neighbor from the new condos stopped by next. He looked uncomfortable but brave. He told us he worked nights and sometimes the engines woke his infant, and he asked if there was any way to cap the hours. Cole apologized without defensiveness and suggested eight p.m. for the next two weeks while we sorted things. The neighbor blinked like compromise was a language he didn’t know we spoke.

“You’ll still testify?” Jenny asked gently, because courage is contagious but not guaranteed. He nodded and said the shop had fixed his flat for free on a day he couldn’t be late to the pediatrician. “I just want sleep and kindness,” he said, and none of us found that unreasonable.

By early evening, our inbox pinged with a link to a blog post claiming “exclusive documents” about an “unlicensed shelter.” The photo was a cot in the back room, the one that had held me when the world didn’t. The caption implied without saying, which is a trick older than law. I breathed through the old shame that flared like a match and went out when it met air.

“Context,” Jenny said, tapping the desk lightly. “Kids in crisis sometimes need a safe place until morning. We coordinate with the clinic and services, and we document. We tell that story simply, and we keep identifying details private.”

Cole rubbed the back of his neck and stared at the cot like it was a horizon line he had marched toward too often. “We kept kids until a grown-up could take over,” he said, voice steady as a tool. “Not to break rules. To keep a heartbeat.” Maya nodded and added the clinic’s intake process to our exhibit list.

As the light thinned, people kept arriving with small pieces of a larger picture. A delivery driver dropped off a stack of bottled water and said the shop had helped him fill out a job application when English tripped him. An older woman from two streets over brought a photo of Cole repairing her space heater during a cold snap, no charge except a story about her husband’s Navy days. None of this would trend, but all of it felt like brick and mortar.

We scheduled witness prep for Thursday evening with a simple script that wasn’t a script. What did you see with your own eyes. What did this place change for you. What would be lost if it closed. We practiced taking oaths with smiles because swearing to tell the truth is a solemn thing that also needs breathing.

When the evening meal came around, Cole pulled out a dented pan and performed his most consistent magic trick: turning inexpensive groceries into food that made conversation easier. We ate standing up on paper plates because sitting felt like tempting the day to fall asleep.

After dinner, I stepped to the whiteboard and wrote the first three rules in thick marker. Go to school. Show up on time. Tell the truth even when it’s the hardest thing you do all week. Beneath them, I added the new one we’d promised to add. Ask for help before midnight. Cole tapped the dog tag to the mug like an amen.

The shop quieted in that way where sound is still but meaning stays awake. I remembered the first night I slept on that cot, the way the heater rattled and the side door clicked once like a secret choosing to be less secret. I thought about what a building can decide to be if the people inside keep choosing.

My phone buzzed with a message from a number I didn’t know. It was short in the way fear is efficient. Is it true they’re closing you Friday. Do you still let people help. I typed yes and yes and added please come early if you want a seat.

Jenny gathered the folders into an order a judge would respect. Maya checked her calendar and circled Friday in a color that meant focus. Cole washed the chipped mugs carefully as if ceramic remembers hands. We turned off the bay lights one by one, letting the room become an outline of everything that had happened in it.

At the threshold, the wind pushed against the door like a question. Cole looked down the alley where the dumpsters waited like old stories and then back at me with a look that said he knew which direction the night could go. “You safe?” he asked, same words, different century. “Come inside.” I locked the door and felt the click like a promise that would have to prove itself in the morning.

We were almost done when Jenny’s laptop pinged again. A scheduling notice had posted to the city site with a small change that wasn’t small. The administrative hearing had been consolidated with a public comment session and moved to a larger room. The line below it said a media pool had requested access.

“Okay,” I said, steadying my breath on the mug’s weight. “We stick to facts, keep our tone calm, and remember we’re not here to win the internet. We’re here to keep a door open.”

Cole set the mug down so softly the tag didn’t ring. He lifted his eyes to mine, and I saw the boy I’d been and the man I was trying to be standing on the same floor. “Then we’ll do what we always do,” he said. “We’ll show up on time.”

Part 4 – Paper Walls and Rumors

Sunday smelled like motor oil and tortillas, which is to say it smelled like home. We opened the bay doors just enough to let the light in and the noise out, an agreement we’d made with the block as part of our “optics plan” that was really just neighborliness written down.

By noon the folding tables were crowded with algebra worksheets, spark plugs, and paper plates. Cole read the rules in his steady range—go to school, show up on time, tell the truth even when it’s hard—and tapped the new one with the back of his pen. Ask for help before midnight. A chorus of “heard” went around the room like a small weather change.

Ms. Alvarez ran flashcards with a seventh grader while Mr. Hurley explained ratios using sockets lined up by size. Maya set up a blood pressure cuff next to the coffee maker and convinced three men who said they “felt fine” to prove it. The condo neighbor from the other day dropped by with a baby monitor and a shy apology; we showed him the quiet-hours sign we’d posted and he smiled like sleep might be possible again.

Jenny arrived with color-coded folders and a checklist that could have held up a bridge. Witness roster, exhibits labeled, procedures annotated for the administrative hearing. “Facts, not volume,” she reminded us, and Cole raised his chipped mug like a toast to plain nouns.

The afternoon settled into a rhythm I remembered from years when Sunday was both the end of something and the beginning. Cole rotated kids through tasks, teaching them how to torque without stripping a thread and how to breathe without stripping themselves. When someone dropped a wrench, he said the same thing he always said. Try again. He didn’t raise his voice; he raised the room.

At three, a city sedan pulled up and an inspector stepped through the door with a clipboard and the polite firmness of someone whose job runs on checklists. We met him at the threshold with hands visible and faces open. He introduced himself, asked if it was a good time, and waited for an answer like it mattered.

“It is,” Cole said, and meant it. He walked the inspector through extinguishers, posted capacities, a neat line of spill kits, and the log showing the bay doors shut by eight for the next two weeks. The inspector checked tags and dates and scribbled notes that sounded like pens make when they’re trying not to be a siren.

When we reached the back room, the cot did what cots do—it looked like a story even when it was only a rectangle of fabric and metal. The inspector paused, eyes traveling from the sheet to the clipboard to Cole’s face.

“That cot,” he said, neutral as a level. “What’s its use?”

“Rest for long shifts,” Cole answered calmly. “When I’m here late or someone needs a breather before they go home. For minors in crisis, we coordinate with the clinic next door and the youth services hotline, and we document referrals. We can provide those logs with names redacted.”

The inspector took the offered binder and flipped through copies of clinic referrals with dates and initials. He nodded in the quiet way people do when something is less mysterious than rumor wanted it to be. “I’ll note the stated purpose and the referral practice,” he said. “Consider adding a posted policy. It helps set expectations—for you and for anyone who comes through that door.”

“Done,” Jenny said, already tapping a draft into her laptop. Cole stood an inch taller, which in his measurement system meant something had gone right.

Out front, a cameraphone lifted and lowered, more curious than hostile. A few heads turned when we closed the doors a little early and switched to hand tools that barely hummed. Kids packed up homework, someone swept, someone else boxed leftovers into dinners that would get eaten in kitchens that didn’t always have Sunday in them.

At six, we walked to the church basement for the neighborhood meeting. Metal chairs squeaked across tile, and a sign-up sheet made its way around the room, rustling like a careful breeze. The facilitator set ground rules that were so reasonable I wanted to frame them: listen fully, speak respectfully, assume good intent until proven otherwise.

The first speaker was a man who worked nights and could name the hours he’d lost to late engines. He was tired, not angry. “I want my kid to sleep,” he said. “I don’t want anyone’s shop gone.” Cole nodded, apologized for the nights we’d pushed the line, and pointed to the quiet-hours plan we’d already implemented.

A teacher spoke next about Saturday math in our back bay and the way some kids learn better when their hands are dirty. A woman from two streets over mentioned a space heater fix in a cold snap. One young resident admitted the bikes intimidated her and then confessed she’d never been inside; Jenny invited her to stop by any afternoon and see the bulletin board where kids post their first pay stubs like trophies.

There were tensions, because there are always tensions when people share walls and Wednesdays. But the room stayed human. By the end, the group agreed to a trial period for the eight p.m. rule, a volunteer crew to repaint the alley with better light, and a contact list for the rare nights when something needed a quick fix before it became a complaint.

Outside, the air had that thin feeling cities get when weather and news combine into a forecast. A glossy flyer flapped under a wiper blade on our car, the ink still wet enough to shine. The headline asked if our block was a dumping ground. The photo was our back room, cropped so the cot looked like a cage and the posted hotline number was just out of frame.

Jenny peeled the flyer off carefully, like it might split if handled wrong. “Don’t let this decide your voice,” she said, sliding it into a sleeve for our file. “We answer what’s true. We ignore bait.”

Back at the shop, we hung a fresh sign above the time clock with the referral steps for minors and the clinic hours with a bold arrow. Cole printed a one-page policy and taped it at eye level. He didn’t sigh when the tape didn’t stick right the first time; he just smoothed it again until it held.

We were almost ready to kill the lights when the shop email pinged with a subject line that knew exactly how to get attention. Public Comment Submission—Urgent. Inside was a scanned letter on generic letterhead with a typed signature block that said “Name Withheld for Safety.” The claims were written in passive voice and heavy ink.

The letter alleged “overnight detention” of a youth “without clear consent” and referred to “a pattern of keeping minors behind locked doors.” It didn’t list dates, but it described the cot and the smell of orange hand cleaner and mentioned the heater rattle like a memory that had grown teeth. My stomach did the old drop it hadn’t done in years.

“Okay,” I said, keeping my tone even like I was guiding a jack under a frame. “We handle this the same way we handle everything else. We provide the referral logs. We document nights when a guardian or service took over. We show our written policy and the clinic’s. And we find out if the writer will speak confidentially to the hearing officer.”

Maya read it once, then the second time slower. “That description reads like scared, not malicious,” she said. “Fear remembers details that paperwork doesn’t. If this person is who I think, I can reach out through the clinic.”

Cole’s hands were steady, which is not the same as unshaken. He set the mug on the counter and let the dog tag rest against it without the tap, as if even that small sound might be misunderstood. “We never locked that door,” he said, voice flat with a hurt that refused to dress itself up. “We kept it closed, and I sat in a chair nearby until a grown-up came.”

“We’ll show that,” Jenny said, already drafting a response for the administrative record that said precisely what it needed to say and nothing extra. “We’ll also prepare for questions about safeguards and add a sign-in sheet for any adult who takes responsibility at transfer. Belts and suspenders.”

I opened the file cabinet and pulled the bin marked Referrals—After Hours. The folders were arranged by month like a quiet calendar. We laid out forms with the same care you use for family photos, because that’s what they were to us: small proof that a night passed, a handoff happened, a door opened again in the morning.

The shop phone rang once and went to voicemail. Then my cell buzzed with a number from the clinic. Maya picked up and listened, her eyes softening into the kind of focus that means a human is more important than a plan. She covered the mouthpiece and spoke so we could hear without the person on the line feeling overheard.

“It’s a young adult,” she said. “They were here years ago when they were fifteen. They saw the flyer and the post and… the letter might be theirs. They don’t want the shop to close. They also want to be believed about how afraid they were that night.”

“Both can be true,” Cole said, and the words landed like a tool put in the right tray at last. “Being afraid doesn’t make you wrong. Keeping you safe doesn’t make me a jailer.”

“Can they meet with the hearing officer privately?” I asked. “We can request that under procedure—allowing sensitive testimony with safeguards. No cameras. Closed session for that portion.”

“Yes,” Maya said into the phone, and then to us. “They’ll come if the door is open.”

I walked to the back room and sat on the chair I used to watch Cole sit in while he waited for a ride to arrive. The heater rattled once, not a threat but a memory doing its job. I stood and checked the lock on the side door and then left it as it had always been on nights like this: closed, not locked, with a note posted at eye level in letters big enough to be read through fear. You are safe here. We will call who you ask us to call. You can leave whenever you choose.

When I came back to the front, Jenny had the response drafted, Maya had the meeting arranged, and Cole had two mugs ready with actual coffee this time, because ritual isn’t superstition, it’s structure. Outside, the alley held its breath the way cities do before mornings that could go one of two ways.

We stacked our files and clicked off the lights and stood for a second in the kind of dark you can only stand in when you know where everything is. The notice on the counter tried to curl and failed. The dog tag tapped the mug once, lightly, exactly enough to count as a promise.

“Tomorrow,” Cole said, opening the door just wide enough to belong to both the night and us. “We show up on time.”

“Tomorrow,” I echoed, reaching for the new sign so I could straighten it one more time. My phone vibrated with a fresh alert before my fingers hit the tape. A news account had posted the letter with the line about “locked doors” pulled out in bold. The caption asked a question that would not help anyone sleep.

Jenny looked at me over the glow of her screen. “We answer at the hearing,” she said, voice firm but kind. “And tonight, we keep the door open for whoever needs to walk through it.”