This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta

The diamond struck first—then came the sound, clean and cold, snapping across the marble like a rule broken in church.

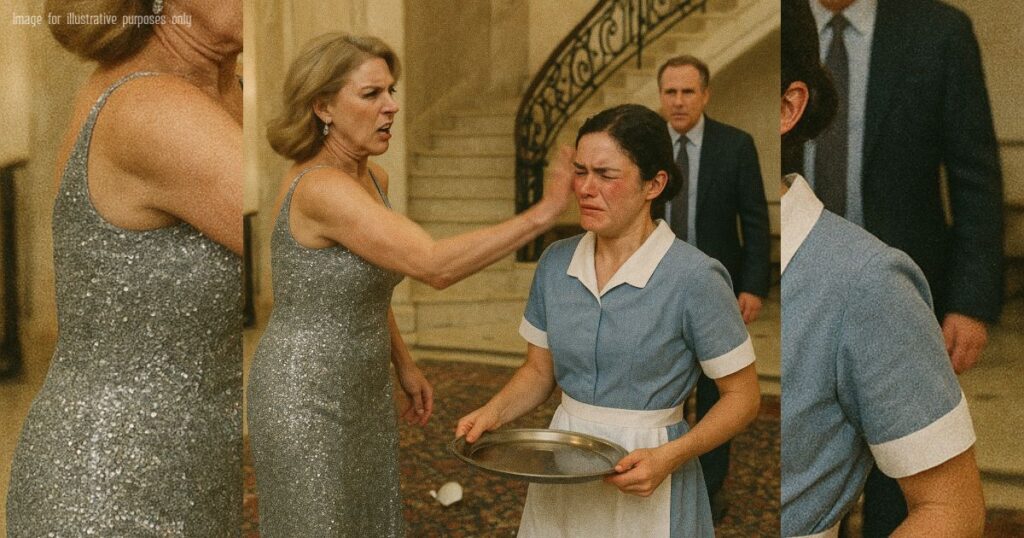

Clara Whitmore, in a silver dress that caught every light, stood with her palm poised in the air as if the moment were a photograph. Her handprint burned pink on the cheek of the new housekeeper. The tray at the young woman’s waist shivered; the porcelain cup it had held lay in fragments at her feet, a pale crescent on the Persian runner.

No one moved. The caterers froze mid-step with folded napkins. The butler’s throat clicked and then stilled. Halfway down the staircase, Thomas Whitmore—husband, benefactor, the name on the charitable wing of two hospitals—stared as though he’d stepped into the wrong house.

“I asked for perfection,” Clara said, each word placed like crystal on a shelf. “This is not perfection.”

The housekeeper steadied the tray. She was small-boned, hair twisted into a practical knot, uniform crisp. “I’m sorry, ma’am. It won’t happen again.”

“It never does,” Clara replied. “They all swear it won’t. Then it does.”

Thomas descended the last steps, his jaw tight. “Clara.”

She didn’t look at him. “Do you know how difficult it is to find people who understand standards?”

The housekeeper—Maya, the new file had said—did not flinch. She set the tray on the console table, gathered the larger shards with a napkin, and kept her gaze on the floor until the room remembered how to breathe.

That night, when the guests were gone and the last of the glass had been swept, the kitchen smelled like lemon oil and exhaustion. Elena, the head housekeeper, poured coffee with hands that had managed four homes in twenty-five years and had seen everything twice.

“You’re the first to make it through a day after that,” Elena murmured to Maya. “Some left before lunch.”

Maya polished a spoon as if it were a mirror and she were fixing her own face in it. “I didn’t come here to leave.”

Elena’s eyebrows rose. “Then why?”

Maya looked at the spoon. She looked at the second hand of the wall clock. She said nothing.

Morning fell into a rhythm. At six, the house exhaled its silence and the staff fit into it: linens fresh, coffee waiting, newspapers ironed, vases refilled. At seven-forty-five, Clara came down like a verdict, checked the fork tines, and found them wanting.

“On the left,” she said, tapping Maya’s layout with a nail lacquered in pale shell. “Left means left. Is the concept too subtle?”

“No, ma’am.” Maya switched the settings in one quiet sweep.

A day became a week. A week learned to call itself a month. Staff whispered wagers in the pantry about how long Maya would last, then lost interest when they kept losing. She didn’t crack. She learned Clara’s coffee temperature by touch, the exact angle the dining chair wanted to be nudged, the cadence of footsteps that meant Clara was about to “inspect.”

Perfection, in that house, was not an achievement. It was a shield.

Thomas noticed first because he noticed last. One evening he paused in the doorway to the library where Maya was polishing silver frames—photos of groundbreakings, ribbon cuttings, checks held like trophies for cameras.

“You’ve been here—what? Five weeks?” he said.

“Six tomorrow.”

He frowned, not unkindly. “Six is a record.”

“I try to be useful,” Maya said.

He nodded and began to turn, then stopped. “The others were… nervous.”

“Fear makes mistakes,” Maya said softly. “I don’t have room for mistakes.”

Something unspoken moved between them and then away, like a guest leaving by a side door.

Clara kept a calendar that looked charitable. Afternoons were “committee meetings,” “site visits,” “board calls.” Nights were “benefits” and “galas,” which were the same party with different themes. Maya learned more from the things the calendar did not say: the days when a designer’s bag arrived at the service entrance in a plain box; the envelopes that were delivered by hand and tucked, without being opened, into a locked drawer in the upstairs dressing room.

One Thursday, Clara was “out.” The house settled into the gentle clatter of a home without its storm. Maya was dusting the molding in the study when the front door opened early and Thomas stepped in. He looked surprised to find any life at all.

“I thought the house slept when the event planner did,” he said, attempting a smile.

“I live in the staff quarters,” Maya replied. “It’s easier to work late that way.”

He studied the neat stacks of correspondence she’d aligned on his desk. “You’re different.”

“Just careful,” she said.

Before he could reply, the door shut again with the soft violence of expensive hinges. Heels clicked, decision by decision, across the marble. Clara was home, and the temperature of the air changed around her.

Maya had learned not to look like she was listening when she was. Passing the master suite that night, she paused only long enough to adjust a picture frame and heard a voice she’d come to know, wrong in its whisper.

“…don’t call here. I said not here. Not now. He’ll be back tomorrow.”

A week later, Thomas left for a two-day trip, the kind he took to keep names on buildings. At breakfast, Clara was buoyant, her smile a perfect prop. By evening, she was gone, too—no itinerary, no call to the house, just the quiet that follows a certainty.

Maya did not make a plan. She followed the one she’d been living.

The dressing room was a different kind of museum: gowns like flags of countries that didn’t exist, shoes that would never touch sidewalks, a vanity spread with jars whose labels whispered chemistry. The locked drawer was shallow, stubborn, and predictable. A hairpin coaxed it open.

Inside lay an envelope the color of expensive stationery and the thickness of a secret that has been repeated. It held hotel receipts from nights when the calendar had said “home.” The signatures were loops and flourishes made by a hand that believed in disguises. There were also photographs—the kind no one prints if they intend to keep anything but the lie: sunset on a marina; a hand on a shoulder; a woman laughing into a kiss.

Maya didn’t take them. She didn’t even hold them long. She took photographs of the photographs, returned everything to the order it insisted on, and shut the drawer without allowing herself to hear it click.

Downstairs, she printed what mattered. Printer paper flattened every smile into the same white. She slid the pages into a plain envelope and set it aside with the morning mail, where the day would find it.

The house met the morning with its practiced grace. Newspapers. Coffee. Flowers that would not wilt until they were told to. Thomas returned at eight-thirty with travel on his suit and gratitude in his eyes for the routine he could step into like slippers. Maya set his cup on the desk and the mail beside it, a small storm tucked into the stack.

She was polishing the dining table when porcelain shattered in the study. It had the high, pure pitch of something that had never expected to break.

“Maya!” Thomas’s call was sharp, but not angry.

She left the cloth where it lay.

He stood behind his desk, the photographs spread before him like a new kind of donor wall. His face had drained of the color that makes a man seem like a person.

“Where did you get these?” he asked.

“They were in the dressing room,” she said. Her voice did not wobble. “In the locked drawer.”

He looked at the envelope as though it might explain itself. “Why bring them to me?”

Maya folded her hands to keep them still. She could have said: because the pediatric pharmacy needs cash up front; because I am tired of people like her deciding the shape of my life; because a bruise on my pride doesn’t change the price of an inhaler. She said none of it.

“Because they’re yours to know,” she said simply.

Evening drew a long breath and then held it. The confrontation did not feel like a scene. It felt like truth arriving so late it apologized with a bow.

Clara denied the first photograph. Denied the second. Called the third “a cruel fabrication.” She attempted outrage, then pity, then laughter that sounded like glass in a pocket. It wasn’t until Thomas held up the receipts—the dates that argued with the calendar, the signatures that couldn’t keep their lies straight—that something in her posture fractured.

“You think she’s some kind of saint?” Clara’s voice lost its polish. “She snoops and steals and imagines herself a crusader. Do you imagine you’ll be rewarded for this?” She turned on Maya like a spotlight. “You’re a housemaid. You dust. You pour. You do not rewrite my life.”

Thomas spoke then, and his voice had the weight of a decision that has already been made. “You rewrote it yourself,” he said. “She just refused to pretend she couldn’t read.”

Silence gathered in the doorway, the way staff do when they cannot help but witness. Elena stood there, hands knotted in her apron, as if she could hold the house together by will.

By the next day, the attorney called. By the next week, the board members called one another, quiet and careful, about the “situation.” Press releases used neutral words that circled the truth without landing on it. The charitable wing did not change its name, but it reprinted its brochures, made a show of audits, discovered grief for the “disruption” and gratitude for “transparency.”

Clara left. She did not slam a door; she managed a farewell with the dignity of someone who intends to reinvent herself in another mirror. The house did not celebrate. It exhaled.

Three days later, Thomas asked Maya to join him in the garden, where the hedges were clipped into certainty and the fountain believed in endlessness.

“I don’t know how to thank you,” he said. “Or how you endured.”

Maya considered the hydrangeas, the way they pretended blue was an accident of soil. “Enduring wasn’t the point.”

“What was the point?”

“Finishing,” she said. “Seeing it through.”

He nodded, the motion of a man who has had to allow someone else to be the hero of his story. “I need a household manager. Someone I can trust.” He hesitated. “It comes with health benefits that may help with—”

“My son,” Maya supplied, not startled that he knew. Elena had always said houses talk; they carry things in their walls and send them where they need to go.

“I can help with the rest,” he said. “There are programs, foundations—legitimate ones. We can—” He stopped, aware he was straying near a line he did not want to cross, the one between generosity and absolution. “I would be honored,” he said instead, “if you would accept the position.”

“I will,” Maya said. “Thank you.”

It would be easy to say the house grew gentle after that. Houses don’t change. People do. The staff moved the way people move when they trust the ground. Thomas traveled less; when he did, he carried the itinerary like an apology. Auditors came and went, trailed by the paper scent of promises kept. In the dressing room, the locked drawer held nothing of interest. Sometimes Maya opened it just to make sure it stayed empty.

On a rain-slow Tuesday, she found herself again in the study, polishing the silver frames. She paused at a photograph she had never really seen before: Thomas with a shovel at a groundbreaking, the caption underneath in tiny serif: A Home for Families. She thought of waiting rooms and vending-machine dinners and the kindness of nurses who were kind even when they had every excuse not to be. She thought of breath measured in numbers, machines that listened for storms in fragile chests. She thought of bills stacked like altars and the quiet, stubborn faith of people who kept showing up anyway.

“Do you ever regret it?” Elena asked from the doorway, having learned how to appear without startling. “Staying. Doing what you did.”

Maya set the frame down, a small precise gesture as if she were returning a crown to its cushion. “I regret the months before it,” she said after a moment. “The practice of swallowing words to keep a roof steady. But the day it mattered, I’m glad I had a throat clear enough to speak.”

Elena smiled, the weary, delighted smile of someone who has seen something true and would like to see it again. “You could have gone to the press,” she said. “You could have burned the whole place down.”

“Fires don’t build anything,” Maya replied. “They just make space. I wanted something to stand when it was over.”

When her son came to visit the first time, he held Maya’s hand the way children hold handrails on boats—like the world is moving and this one thing can be trusted. Thomas was careful and brief and funny, the way adults are when they don’t want to scare a child with the size of their gratitude. He sent them away with a box from the bakery that the boy held as if it contained a pet.

They passed the hallway on their way out. The runner had a pale crescent near the base of the stairs where a porcelain cup had once found a way to break. The stain had never fully disappeared, no matter how many treatments it had endured. If you knew where to look, it was there.

Her son traced it with his eyes. “What happened?” he asked.

“A small thing that turned into a big change,” Maya said.

“Like a hinge?” he said, newly in love with metaphors he had earned the right to use.

“Exactly,” Maya said. “Like a hinge.”

She didn’t tell him about the drawer or the envelope or the way a house can swallow a secret until someone teaches it a new language. She didn’t tell him about hands and what they sometimes have to bear. She told him they would be on time for his appointment if they walked quickly. And they were.

The weeks kept their promises. The house learned where Maya liked the vases. The staff found that a room can be both immaculate and kind. The board, chastened by headlines that never quite printed, instituted policies that would have sounded good even without the scandal. The foundation’s money drew straighter lines: from donor to clinic, from gala to infusion, from speech to breath.

Sometimes, late, when the dishwasher hummed and the last lamp in the foyer threw a soft coin of light on the floor, Maya would stand beneath the staircase and look up. She would think of the first night, of a hand raised like a photograph and a house that forgot how to move. She would remember choosing to remain. People mistook that choice for surrender. It had never been surrender. It had been strategy, a patience sharpened into a tool and held until the moment it was needed.

One evening, she found Thomas at his desk with a pen he was not using and papers that did not require his attention.

“What is it?” she asked.

He lifted a sheet and let it fall. “I keep wondering,” he said, “how many times someone stood here and knew something I needed to know, and I made it too hard for them to tell me.”

Maya thought of drawers and doors and throats and the ways they were all the same. “Maybe ask,” she said. “And then listen like you believe them.”

He nodded. “I’m trying.”

“That’s all a house can ask,” she said. “That and a decent polish now and then.”

He laughed, and the room remembered how to be a room again.

The diamond that had struck first that night did not live here anymore. It lived somewhere else, on a different hand, telling a different story to whatever light would listen. The house did not miss it. The house had learned other ways to shine.

If you stood very still in the foyer and listened with the kind of patience that takes months to practice, you could hear the smallest hinge carrying weight without complaint. You could hear breath in a different house, measured but free. You could hear a story that had chosen a quiet ending because it hoped to make a longer beginning.

It would be tempting to call what happened a victory. It felt, to Maya, like something more useful than that. Victory is a finish line. What they made together—however awkwardly, however late—was a foundation.

And if she ever caught herself in the mirror of the dressing room as she passed, she did not look too long. She had work to do. She had rooms to keep ready for the lives that would happen in them. She had a boy who slept more easily and woke more often without fear. She had a drawer that held nothing but air.

In the end, no headline ever told the story as it had lived in those walls. They never do. Houses keep their own records. Sometimes, if you’ve earned it, they let you read them.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!