Part 1 – The Night a Barefoot Boy Ran to a Broken Soldier

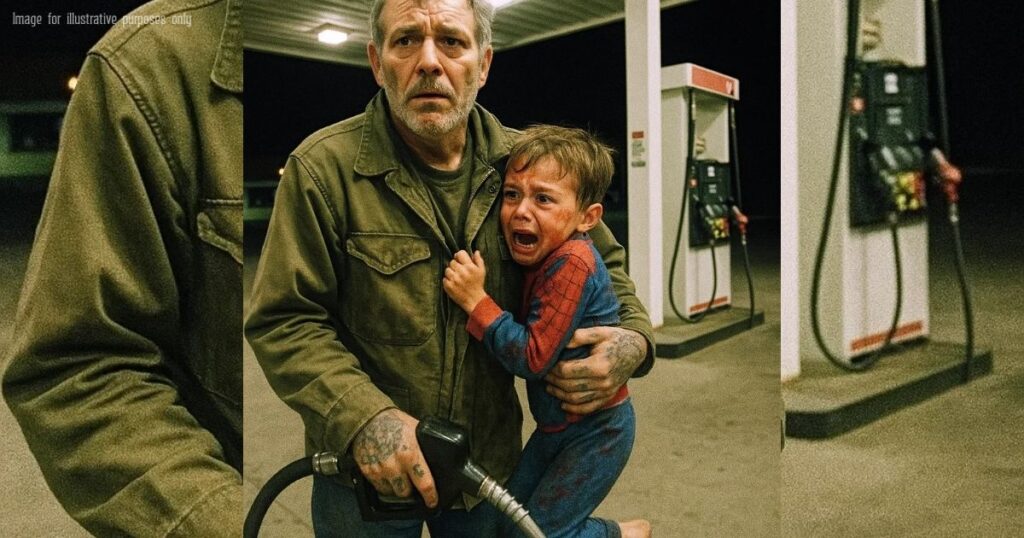

The boy in blood-smeared Spider-Man pajamas slammed into my chest at two in the morning, begging me to pretend to be his dad before the man in the shiny SUV could take him back. By the time my brain caught up, his bare feet were already leaving little half-moons of dirt and road salt across the concrete.

I was halfway through my shift at the highway gas station, standing under a flickering canopy light, filling my thermos with burnt coffee and trying not to think about the past. My name’s Jack Walker, but most people around here just call me “that weird vet with the tattoos.” I wear an old army field jacket, keep my hair too long, and my face too tired. The teenagers who drift through at night don’t know what to make of me, so they don’t.

The boy came out of the dark like a thrown object, small body colliding with me so hard I had to grab the pump to keep from losing my balance. His arms clamped around my waist, his fingers bunching the fabric of my jacket. Up close I could see the purple-yellow shadows on his wrists, the dried line of red at the collar of his pajama top. His breathing was so ragged I could feel it shaking through my ribs.

“Please,” he gasped, staring up at me with eyes too big for his face. “Please pretend you’re my dad. Don’t let him take me back. Please, sir, please.” His voice cracked on the last word, like it ran into a wall of terror. And behind him, cutting across the empty lot, came the low growl of an engine turning too fast into the entrance.

The SUV rolled under the canopy and stopped so close I could see the bug splatters on its grille. The driver’s door opened and out stepped the kind of man small towns trust without thinking. Clean-shaven, pressed polo shirt, wedding ring flashing under the lights, the easy half-smile of someone used to getting the benefit of the doubt. He looked like a coach, or the kind of dad who brings extra snacks to practice.

“Hey there, buddy,” he called, voice warm like a commercial. “There you are. You scared your mom half to death, running off like that.” He glanced at me, then at the boy still glued to my side. “Sir, I’m so sorry if he bothered you. He has… issues. Gets confused. I’m his stepdad. Ryan.”

The boy’s fingers dug deeper into my jacket. “He’s lying,” he whispered, not loud enough for Ryan to hear, but loud enough to slice through the space between us. His whole body was shaking like he’d been standing outside in a storm for hours, not seconds. I could smell night air and cheap detergent and a faint metallic tang I really hoped wasn’t as fresh as it looked.

I cleared my throat, trying to find the line between “not my business” and the way my stomach had just dropped into my boots. “Didn’t see where he came from,” I said evenly. “Kid just ran up. Lot of cars pass through here.” My voice came out calmer than I felt. Years ago I learned how to sound steady while my mind screamed.

Ryan chuckled and took a few easy steps closer. “He does this,” he told me, like we were sharing an inside joke. “Gets an idea in his head and runs with it. Makes up stories. Doctors think it’s a coping thing. Isn’t that right, Noah?” He tilted his head at the boy, still smiling, but his eyes were cutting, sharp and mean.

The name hit the kid like a slap. He flinched without being touched. His nails bit into my side as he whispered, barely moving his lips, “He hurt my mom. Tonight. She told me to run. He said if I told anyone he’d make it look like I was crazy. Please don’t let him take me back. They never believe me.”

For a second, the gas station fell away. The hiss of the pump turned into the hiss of a ruptured line overseas, the smell of gasoline into the copper stink of blood in desert heat. Another small body, another pair of eyes begging me to do something, anything, before it was too late. My therapist says that’s what trauma does, folds time like paper until old scenes bleed into new ones.

I forced myself to breathe and look at what was in front of me, not behind me. A well-dressed man, careful posture, expensive watch. A child in pajamas in the freezing night, bare feet, bruises not quite hidden by cartoon fabric. One of them had chosen to run toward me instead of away. I’ve learned that means something.

“Look, man,” Ryan said, the smile tightening at the edges. “I don’t want trouble. You seem like a decent guy. But he belongs with his family. I’ll handle whatever’s going on. You know how kids are.” He lowered his voice, suddenly sympathetic. “And I know your type too. People talk. Hard time adjusting after service, right? Sometimes vets… misread situations.”

There it was. The warning shot. If this went bad, I was the unstable ex-soldier who’d “snapped” at a gas station. The story practically wrote itself. Out by the road, a car slowed, its driver rubbernecking, then moved on, the moment swallowed again by ordinary darkness.

Noah’s grip didn’t loosen. “If you let go of me,” he breathed, “he’s going to say I ran toward him, not away. He always flips it. Please.” His voice didn’t sound like a kid playing a game. It sounded like someone clinging to the last rung of a ladder over a pit.

My phone was in my pocket, heavy as a decision. I angled my body, shielding Noah with my frame, and slid it out, thumbing the camera on without looking. “Noah,” I said quietly, so only he could hear, “I need you to answer one thing. Did you come to me on your own because you were scared?”

“Yes,” he said, right away, like he’d been waiting his whole life to be asked the right question. “I ran to you because you looked like you could fight him. And because you didn’t smile like he does.”

Headlights swept past again, then another set, and finally the sharp blue-red pulse of a cruiser turning into the lot. The kid stiffened, his nails biting crescent moons into my skin. Across from us, Ryan exhaled, shoulders dropping with relief he didn’t bother to hide.

The patrol car rolled to a stop, lights washing the pumps in color. The driver’s door opened, and an officer stepped out, adjusting his belt, eyes flicking from me to Noah to Ryan. Then he smiled, just a little.

“Evening, Ryan,” he called, like they were meeting at a backyard barbecue. “Heard you’ve got yourself a situation.”

Noah’s breathing turned into tiny, panicked hiccups. The officer started walking toward us, slow and easy, like he already knew exactly how this was supposed to end. And right then, with sirens echoing faintly in the distance and a child glued to my side like a life jacket, I realized I had maybe ten seconds left to decide whether I was going to obey the law… or finally break it to save a child.

Part 2 – When the Law Shows Up and Has Already Picked a Side

The officer’s boots crunched on the gravel as he crossed the lot, one hand resting easy on his belt like this was a noise complaint, not a kid clinging to a stranger in the middle of the night. Up close he smelled like coffee and cold air and the faint trace of aftershave. I noticed the lines around his eyes deepen when he smiled.

“Evening, Ryan,” he said again, stopping closer to the SUV than to us. “Dispatch said your boy bolted on you.” He finally turned his attention to me and Noah, but it felt like an afterthought. “Sir, I’m Officer Keller. Mind telling me what’s going on?”

Ryan spoke before I could. “It’s really simple,” he said, laughing lightly as if this were all a misunderstanding. “Noah had a meltdown, ran out of the house, I followed him, he ran up to…” He gestured at me with a little shrug. “This gentleman. Scared him half to death, I’m sure. Kid’s on meds, has some behavioral stuff. We’ve been dealing with it for a while.”

Noah’s fingers tightened around my jacket hard enough to hurt. “I’m not on meds,” he whispered, barely moving his mouth. “He told Mom she couldn’t afford them. He just tells people that.” His breath came in short bursts against my ribs. I could feel his heartbeat racing like it was trying to punch its way out.

I cleared my throat. “He didn’t stumble into me,” I said, forcing my voice to stay level. “He ran straight to me. He said he was scared and asked me to pretend to be his dad so you wouldn’t take him back.” I didn’t raise my voice, didn’t step forward, didn’t do anything they could later call “aggressive.” You learn that after you come home in one piece and still feel like you’re one bad moment away from losing everything.

Officer Keller’s eyes flicked to my jacket, taking in the faded unit patch, the ink on my hands, the lines in my face. I saw the calculation behind his gaze. “I understand you’re concerned, sir,” he said, using the tone people use with unstable explosives. “But this is a family situation. We handle these carefully. Why don’t you let go of the boy so we can get him back to his parents and let the professionals sort it out?”

Noah buried his face in my side. “Please don’t,” he said, and the sound of it cut through me sharper than any order I’d ever been given. “He hurts us when they leave. He says it’s our fault he had to call them. Please, please, please…”

“Us?” I asked, almost without meaning to. “There someone else at home?”

Noah swallowed. “My mom,” he said. “She was bleeding when I ran. She told me not to look back.”

For half a second, everything in the lot went very still. Even the pump seemed to hush. Ryan’s smile didn’t move, but his jaw did. A small muscle twitched near his temple. “He’s confused,” he said quickly. “His mom had a little accident in the kitchen earlier, cut her hand. She’s fine. She’s resting. Right, buddy?”

Headlights washed over us again as another patrol car pulled in, this one parking at an angle that lit the whole scene like a stage. The second officer stepped out, younger, darker circles under his eyes, taking the picture in without greeting anyone by name. His gaze went first to Noah’s bare feet, then the smear of red on his collar, then to the way the kid’s fingers were welded into my coat.

“Evening,” he said, voice neutral. “What’s the story?”

Keller summarized quickly, in the clipped shorthand of someone who thought he already knew how this ended. “Kid with history, veteran passerby, misunderstanding.” He didn’t say “unstable,” but the word hung there anyway.

I raised my phone just enough that the screen glowed between us. “I started recording when he ran up to me,” I said. “You can see how he came here, what he said. You’ll hear his exact words about why he’s scared.” I met the younger officer’s eyes. “If I’m misreading this, at least the record will show I tried not to.”

Keller’s gaze sharpened. “Sir, I’m going to need you to put the phone away for now,” he said. “You can share anything relevant down at the station if it comes to that.”

The younger cop—his badge read HERNANDEZ—didn’t move for a moment. “Let him keep it rolling,” he said calmly. “We’re all on camera anyway.” He nodded toward the station security lens blinking red above the door. “No harm in one more angle.”

Ryan shifted, annoyance flickering across his face before he smoothed it over. “Officer, can we please not turn this into a circus?” he said. “My wife is home alone, upset, waiting for us. She asked me to bring him back, not spend half the night on paperwork.”

Hernandez crouched slightly so he was more level with Noah. “Hey, Noah,” he said gently. “Can I talk to you for a second, just you and me? We’re going to make sure you’re safe, okay? But I need to hear from you.”

Noah didn’t let go of me. “If I go with you,” he whispered, “are you going to give me back to him after?”

“That depends on what you tell us and what we find out,” Hernandez replied. He didn’t make promises he couldn’t keep. I respected that. “My job is to listen and to look. Not just to take anybody’s word for it. Not his. Not yours. Not his.” He tipped his head toward Ryan, then me.

Slowly, like peeling a bandage off skin, Noah loosened his grip on my jacket. He didn’t step away; he just turned slightly so he could see Hernandez while still touching my side. “He hurt my mom,” he said, louder now, voice shaking but steady. “Not in the kitchen. He pushed her. She hit her head. There was blood on the floor, not just her hand. He told me to stop crying or he’d make sure nobody would ever listen to me again.”

Ryan let out a short laugh that sounded like it had sharp edges. “This is what I mean,” he said to the officers. “Stories. He watches too many movies. He has a wild imagination. We’ve been in and out of counseling for years. The doctor said not to feed into the fantasies.”

“Doctor’s name?” Hernandez asked, not looking at him.

Ryan hesitated. “It’s in my phone,” he said. “Look, are we really doing this here? In the middle of a parking lot?”

Keller sighed, shifted his weight. “All right,” he said. “Here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to take everybody down to the station. Get statements. Maybe send someone by the house to do a welfare check just to be safe. That work for you, Ryan?”

Ryan’s smile slipped for the first time. “I don’t see why that’s necessary,” he said slowly. “But if it makes you feel better, fine. I just don’t want to upset my wife more than she already is.”

Hernandez looked at me. “Sir, I’m going to ask you to step back and let me walk Noah to the car,” he said. “You can follow us in your own vehicle or ride with Keller. You are not under arrest at this moment. Do you understand?”

There it was again, the line drawn on the ground. Obey or don’t. Trust or bolt. My mind flashed through scenarios like a slideshow. Grabbing the kid and running. That ended with guns drawn and headlines about veterans gone rogue. Doing nothing. That ended with a child handed back to someone he was sure would hurt him.

I slipped my phone into my pocket without stopping the recording. “Noah,” I said, keeping my voice low. “You go with him. Officer Hernandez is listening. You keep telling the truth, exactly like you did just now. I’ll be right behind you. I’m not going home.”

He looked up at me like he was trying to decide whether to believe me. “You promise?” he asked.

“I’ve broken a lot of things in my life,” I said. “But I don’t break promises to kids.”

Hernandez gave Noah a small, encouraging nod and held out his hand. After a long breath, Noah took it. They walked toward the second cruiser together, the boy’s bare feet slapping softly against the cold concrete. Halfway there he glanced back at me. I raised my hand, not waving, just letting him see I was still there.

Keller stepped closer. “You got ID on you, Mr…?”

“Walker. Jack Walker,” I said, handing over my worn license. He glanced at it, then at me, and something almost like recognition crossed his face.

“We’ve had a couple calls about you,” he said. “Nothing serious. People get nervous about men hanging around kids these days. I’m sure you understand.”

“I get nervous about it too,” I replied. “That’s why I pay attention when one runs toward me instead of away.”

We rode to the station in separate cars. Ryan in the back of Keller’s cruiser, Noah in the back of Hernandez’s with a blanket around his shoulders, me in my old truck following the shifting pattern of their taillights. The highway was nearly empty, a long black ribbon stretching toward a town that had never quite figured out what to do with people like me.

At every red light, my fingers twitched with the urge to turn the wheel, to disappear down some side road and never come back. But then I’d picture Noah’s face when he said, “They never believe me,” and my foot stayed on the brake.

The station was bright and humming under fluorescent lights when we pulled in. Hernandez led Noah inside through a side door. Keller walked Ryan in through the main entrance like they’d done this dance a hundred times. I locked my truck, pocketed my keys, and followed. The automatic doors whooshed open, and the smell of stale coffee and disinfectant hit me like a memory.

They sat me in a small interview room with a metal table and two chairs, the kind of room where stories either become reports or get filed away as misunderstandings. Hernandez came in a few minutes later, holding my license and a styrofoam cup.

“I’ve got an officer on the way to the kid’s house now,” he said, setting the cup in front of me. “Welfare check. We’ll see what’s what.”

My mouth was dry. “And if there’s nothing?” I asked. “If the kitchen’s clean and his mom says everything’s fine because she’s scared or he got the details wrong?”

Hernandez studied me for a moment. “Then this goes in a file like a lot of other messy, complicated things,” he said. “But that’s not what I’m betting on.”

He glanced at the one-way glass, then back at me. “Neighbor just called in,” he added quietly. “Said she heard a scream and something like furniture breaking about an hour ago. Said she saw the boy run. Said she saw the stepdad’s truck follow. She was afraid to call until she saw the patrol car outside.”

My chest tightened. I wasn’t sure if the feeling was relief or dread. Maybe both.

Hernandez pulled out a small digital recorder and set it on the table between us. He pressed the red button, the light blinked on, and he leaned back in his chair.

“Okay, Mr. Walker,” he said. “Start from the beginning and tell me why you decided to get involved. And this time, I’m going to make damn sure it doesn’t disappear into a drawer.”

Part 3 – The Boy Who Cried Monster — and Was Finally Heard

Hernandez clicked the recorder on and folded his hands, like we were about to talk about parking tickets instead of a kid with dried blood on his collar. The little red light blinked between us, patient and unblinking.

“State your name for the record,” he said.

“Jack Walker,” I replied. “Sergeant, United States Army, retired.” The word “retired” always felt like a lie. I hadn’t retired; I’d just stopped being useful.

He nodded once. “Okay, Mr. Walker. In your own words, tell me what happened tonight from the moment you first saw the child.”

I took a breath and tried to unwind the last hour without letting my brain slip backward into other nights, other small bodies, other dark stains on concrete. “He didn’t just appear,” I said slowly. “He hit me like he’d been thrown. Ran straight across that lot like his life depended on it, grabbed me, and asked me to pretend to be his dad before ‘the man in the shiny SUV’ got there.”

Hernandez didn’t look away, didn’t write anything yet. “Exact words matter,” he said quietly. “You remember them clearly?”

“I do,” I said. “You don’t forget it when a kid looks you in the eye and says, ‘They never believe me.’ I’ve heard that sentence before. Different language, same sound.”

“Where?” he asked.

“Another country,” I said. “Another kid who didn’t make it. That’s not why we’re here.”

“Maybe not,” Hernandez said. “But it tells me why you got involved when a lot of people wouldn’t have.” He gestured for me to go on.

I told him about the SUV, the way Ryan stepped out already smiling, already apologizing for the “misunderstanding.” I described the way Noah’s hands locked up when he heard his name spoken in that tone, the way his shoulders flinched every time Ryan took a step closer. I repeated the thing about “doctors” and “meds” and how Noah had whispered that there were no doctors, no meds, just threats.

Hernandez finally picked up his pen. “You’re sure he said his mom was bleeding from her head, not just her hand?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “He didn’t say it like a kid who scraped a knee. He said it like someone who’d seen too much and knew nobody would buy it unless he got the details right.” I paused. “I’ve heard grown men lie about injuries. He didn’t sound like them.”

The pen scratched softly. On the other side of the glass, I heard a faint echo of voices—higher, smaller, one of them breaking into hiccuping sobs. My ears have always been too good; sometimes I hate that.

“That’ll be the intake room,” Hernandez said, catching my glance. “Child advocate and a detective. We don’t question minors alone.”

“Good,” I said. “He’s had enough of men in rooms telling him how he feels.”

The door opened and Keller stuck his head in. The fluorescent light washed him out, made him look older. “Patrol just checked in,” he said. “At the house. They found the front door cracked open. Glass on the kitchen floor, signs of a struggle in the living room. Woman on the floor. Breathing, but unresponsive. EMS is transporting now.”

My throat closed around the air I was trying to swallow. I hadn’t realized how much I’d been bracing for the other outcome until I heard the word “breathing.”

“Any sign of forced entry?” Hernandez asked, his pen hovering.

“No,” Keller said. “No sign of anybody else. Neighbor across the street said she saw the boy run out barefoot, man chasing him a minute later. Says she’s heard yelling over there a lot. Never called before tonight.” He rubbed a hand over his jaw. “Says she didn’t want to ‘cause trouble.’”

“Trouble’s already there,” I muttered.

Keller’s eyes flicked to me, then away. “She also said the wife showed up at her door last month with a bruise on her cheek, said she’d bumped into a cabinet. Neighbor didn’t buy it. They had coffee, then the husband came knocking, all apologies and flowers the next day.”

Of course he did, I thought. Monsters rarely forget the roses.

Hernandez jotted a few words down, then nodded toward the hall. “Have them secure the scene, bag anything obvious,” he said. “And get photos of the injuries, both tonight’s and whatever’s in the neighbor’s texts if she’s got any. We’ll need a full timeline.”

Keller hesitated in the doorway. “Ryan wants to know if he can go home,” he said. “Says his wife will need him at the hospital. Says this is all ‘blown out of proportion.’ His words.”

“He can wait,” Hernandez replied, the first hint of steel in his tone. “He’s not under arrest yet, but he’s not walking out while we’re still figuring out whether the woman he lives with is between ‘injured’ and ‘dead.’”

Keller grimaced. “You know this is going to get messy,” he said. “He’s on every volunteer list in town. People like him. People talk about him doing ‘so much good.’”

Hernandez met his gaze head-on. “Then people can sit with the discomfort of not knowing someone as well as they thought,” he said. “It’s 2025, Mike. We don’t get to act surprised every time a ‘good guy’ turns out to be a problem behind closed doors.”

Keller closed the door behind him on his way out. The room settled again, the air too thick.

Hernandez looked back at me. “You all right?” he asked.

“No,” I said honestly. “But I’m here.”

He let that sit for a moment. “You ever had contact with the kid or the family before tonight?”

“No,” I said. “But I’ve escorted enough families to casualty notifications to recognize the look on a person’s face when they realize they’re about to lose everything. That boy had it from the moment he hit my chest. He wasn’t playing a game.”

“Some kids do,” Hernandez said matter-of-factly. “They exaggerate. They get scared and twist things up. That’s real too. Our job is to sort it out, not pick a favorite story.”

“Sure,” I said. “But there’s a difference between a kid who lies because he broke a window and doesn’t want to get grounded, and a kid who lies because every time he tells the truth, it makes things worse. You get enough of the second kind, you start to hear it in the way they breathe.”

Hernandez studied me. “You sound like you’ve sat across from a lot of scared people,” he said.

“I have,” I said. “Some of them died anyway.”

I don’t know why I said that out loud. Maybe because the room already felt like a confessional. Maybe because I was tired of carrying ghosts quietly.

“Is that why you recorded him?” Hernandez asked. “Because you didn’t trust us?”

I let out a short laugh that didn’t feel like laughter. “I don’t trust systems,” I said. “People in them, sometimes. Systems, no. I’ve watched too many people disappear between lines on a form. I figured if I was wrong, I’d have wasted some storage space on my phone. If I was right, maybe that video would keep somebody from deciding he ‘changed his story’ later.”

Hernandez tapped the pen against his notepad, thinking. “We’d like a copy of that,” he said. “We’ll log it into evidence. You’ll keep the original for now.”

“That’s backwards from what I expected,” I said.

“Welcome to the part where I’m trying to do this right,” he replied. “You’re not the one under the microscope tonight. At least not the only one.”

The door opened again. This time it was a woman in a dark cardigan and sensible shoes, hair scraped back in a bun that had started to lose the fight. She carried a folder and the kind of fatigue you only get from spending your days listening to stories nobody wants to believe.

“Jack Walker,” Hernandez said, gesturing between us. “This is Ms. Alvarez. She works with child services.”

She offered her hand. Her grip was firm, no nonsense. “You were the one he ran to?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “He picked me out of all the wrong people.”

“There’s no such thing as the wrong person when a kid runs toward you,” she said softly. “There’s only what you do next.”

Something in my chest unclenched at that. “How is he?” I asked before I could stop myself. “Noah.”

Alvarez glanced toward the hall. “Shaken,” she said. “Exhausted. Very worried about his mother. But consistent. Details match what the neighbor reported. Matches what officers found at the house. That doesn’t happen as often as you’d think.”

Hernandez raised his eyebrows. “He mentioned previous incidents?”

She nodded. “Said he’s tried to tell grown-ups before. A school counselor. A youth pastor. A neighbor once. Said they all told him he ‘misunderstood’ or that his stepfather was ‘just strict.’” She flipped open the folder. “We’re pulling prior reports now. There are a couple of notes from hospital visits that look… interesting.”

“Interesting good or interesting ‘we missed it’?” Hernandez asked.

“Both,” she said. “We’ll see.”

For a moment none of us spoke. The fluorescent lights hummed overhead, steady and indifferent. Somewhere down the hall, a door clicked, a chair scraped, life went on.

“What happens to him tonight?” I asked finally. “To Noah.”

“He’ll stay here a while longer,” Alvarez said. “We’ll get him checked by a doctor, make sure he’s not hiding injuries. Then we’ll decide whether he can safely stay with a relative or needs a temporary placement. We’ll know more when we hear from the hospital about his mom.”

“And him?” I jerked my chin in the vague direction of the rooms where I assumed Ryan was sitting, probably spinning his version of events.

“Right now he’s a person of interest in a domestic assault,” Hernandez said. “Depending on what the hospital says and what we find in those prior records, that may change.”

“But he’s not in cuffs,” I said. It came out sharper than I meant.

“Not yet,” Hernandez said. “You only get one chance to do this clean. If we rush and screw up the paperwork, his lawyer will have a field day. You want him to walk because we were in a hurry?”

I thought about fast decisions made in dusty tents, about what it costs to cut corners when lives are involved. “No,” I said. “I want him in a cage because you did it right.”

Hernandez gave a thin, humorless smile. “Then let us do it right,” he said.

Alvarez closed her folder. “One more thing, Mr. Walker,” she said. “When Noah talked about running to you… he said he picked you because you looked ‘scary enough to fight a monster but sad enough to listen.’ His words, not mine.”

Something hot pricked behind my eyes, unexpected and unwelcome. I stared at the tabletop until it passed. “He’s got a good eye,” I managed.

She studied my face like she was filing it away. “We’re probably going to need you again,” she said. “Statements, maybe court if this goes that far.”

“If?” I repeated.

Alvarez glanced at Hernandez. They exchanged a look that told me they’d both seen too many things stall out halfway. “Let’s just say I’ve seen cases like this fade away when people get tired, or scared, or pressured,” she said. “The more adults stand where they stood tonight, the harder that is to happen.”

The room felt smaller suddenly, the walls closer. I had come in here thinking my job might be over once I handed the kid to uniformed hands. Now it was dawning on me that tonight had just been the first step onto a road that would be a lot longer and uglier than a drive to the station.

Hernandez reached over and stopped the recorder. The little red light clicked off, but the weight of what we’d said stayed on the table between us.

“Get some water,” he said. “Use the bathroom. Don’t leave the building. We’re far from done here, Mr. Walker.”

I stood up on stiff legs and opened the door. The hallway buzzed with quiet activity, phones ringing, printers chattering, boots on tile. Somewhere down the corridor, behind another closed door, a nine-year-old kid was trying one more time to convince a room full of adults that the monster lived in his own house.

For the first time in a long time, I knew exactly which side of that door I was meant to be on.

Part 4 – Inside the Case File That Almost Failed Noah

By the time I opened Noah’s case file on my screen, the sky outside the child services office had turned from black to a tired gray. The building hummed with the low, constant noise of vents and old lights, the kind of sound you stop hearing until you realize you never get real quiet anymore. Nights like this had a way of stretching into each other until you forgot which crisis belonged to which day.

My name is Maya Alvarez. On paper, I’m a child protection specialist. Before that, I was Staff Sergeant Alvarez, Army medic. The uniforms are different, but the job feels familiar: show up after something bad happened and try to keep it from getting worse.

Noah’s digital file blinked open with a list of dates down the side. Little blue lines, each one a moment someone thought something might be wrong. School incident reports. A couple of emergency room visits. A note from a church youth program about “emotional difficulties.” None of them had ever added up to action.

I clicked the oldest report first. Two years ago. Nurse at an urgent care writing, “Child presents with bruising on upper arms and back. Caregiver states he fell off a backyard play set. Child is quiet, avoids eye contact, shrugs when asked what happened. Caregiver attentive, appropriate. No disclosure. Advised follow-up with pediatrician.” Case closed as “inconclusive.”

The next one was from a school counselor: “Student appears withdrawn, anxious. Reports ‘being scared at home sometimes’ but refuses to elaborate, then laughs it off. Stepfather present at meeting, very engaged, attributes behavior to ‘adjustment issues’ after remarriage. Provided resources for ‘big feelings.’ No further action at this time.”

I felt my jaw tighten. I’ve read hundreds of these. Nobody did anything wrong, not exactly. They did what the guidelines said, checked the boxes they were trained to check. And still, here we were.

I opened the hospital record from three months ago. “Mother presents with rib contusion after alleged fall in shower. Nine-year-old son appears highly distressed in room, repeatedly says ‘it was loud this time.’ Mother insists injury was accidental. Stepfather calm, cooperative, holds mother’s hand throughout exam.” Another note in the margin: “Consider stress-related family dynamics. No clear evidence of assault.”

I leaned back and rubbed my eyes. Somewhere down the street, the first morning bus sighed past. The world was getting ready for another normal day, and in this building we were still sorting through the leftovers of the night before.

On the desk beside my keyboard sat the thin paper file we’d started tonight. Emergency note from officers at the scene. Preliminary statement from Noah. Intake summary. “Suspected domestic violence. Child alleges stepfather pushed mother, causing head injury. Child reports ongoing pattern of physical and emotional abuse. Prior concerns on record; none previously substantiated.”

I scrolled to the bottom of the digital file and saw a line that hadn’t been there an hour ago. “New collateral contact: neighbor across the street. Willing to speak. Provided phone number.” I picked up the desk phone before I could talk myself into waiting until a more civilized hour.

She answered on the second ring, voice thin and shaky. “Hello?”

“Ms. Chen?” I asked. “My name is Maya Alvarez. I’m with county child services. The officers said you might be willing to talk about what you’ve seen next door.”

There was a pause, then a soft exhale. “I should have called sooner,” she said. “That’s what you’re thinking, isn’t it?”

“I’m thinking this is hard,” I said honestly. “And you’re calling now. That matters. Can you tell me what happened tonight in your own words?”

She described the scream, the sound like something heavy hitting a wall, the sight of Noah running across the street in his pajamas. The way he banged on her door and then froze when the stepfather’s truck engine revved. How she watched from behind the curtain as the boy ran down the block toward the main road, and the truck followed a minute later.

“Have you ever seen anything like this before?” I asked.

Another pause. “I’ve heard arguing,” she said. “Not every night. But enough. A man’s voice, loud. A woman’s voice trying to stay calm. Sometimes the boy. Once, last month, she came over in the afternoon. Said she’d walked into a cabinet. The bruise didn’t look like that. I made tea. She cried a little. Then he knocked on my door with flowers and jokes, and she said everything was fine in front of him.”

“Did you take any pictures?” I asked, more out of habit than hope.

“I did,” she said, surprising me. “My sister told me to. Said if I ever felt something was wrong, I should keep records. I didn’t know who I would ever show them to. I just… I didn’t want to feel crazy.”

We arranged for her to text the photos to a secure number. They came through a minute later: a woman with tired eyes and a purple bloom on her cheekbone, trying to smile like it was a joke. A blurry shot of broken dishes in a trash bag on the curb, shards of something that had clearly met a wall before it met the bin.

I added them to the file, labeling each one carefully. Every image was a puzzle piece. The picture still wasn’t complete, but the edges were starting to connect.

As I worked, a thought I’d been pushing aside kept nudging at the edge of my mind. Jack Walker. The veteran at the gas station. The way his shoulders sat like he was still wearing body armor. The way his eyes had tracked every movement in the room while pretending not to.

I’d seen men like him in the VA waiting room, staring at the same spot on the wall while daytime television played too loud in the background. I knew that look because some mornings it was my look in the mirror.

I logged out of Noah’s file for a moment and pulled up another screen. Quick search. Military service record. He’d done two tours as a medic in a place everyone was tired of naming on the news. Commendations. Honorable discharge. Nothing in the public record that said “dangerous,” just the usual phrases: “difficulty adjusting,” “seeking treatment,” “limited social support.”

People love easy categories. Hero or threat. Stable or broken. Safe or scary. The truth is most of us live somewhere in the middle, trying to make it from one day to the next without tipping too far in either direction.

My cell buzzed on the desk. Hospital caller ID. I picked up. “Alvarez.”

“Ms. Alvarez, this is Dr. Patel in the emergency department,” a calm voice said. “I’m calling with an update on Emma Morrison. She’s the mother involved in your case?”

“Yes,” I said, already bracing. “How is she?”

“She’s stable for now,” he said. “Subdural hematoma, significant concussion, multiple contusions. We’ve taken her to surgery to relieve the pressure. If all goes well, she’ll be in intensive care for at least a couple of days. She is not currently able to consent to interviews or decisions.”

“Any indication the injury could have been accidental?” I asked, because that was my job even when I hated the question.

He was quiet for a beat. “Anything is possible,” he said carefully. “But the pattern of her injuries is not consistent with a simple fall in the kitchen. The treating team has filed a mandatory report for suspected assault.”

“Thank you,” I said. “Please note in her chart that child services will need to speak with her as soon as she’s awake and medically cleared. And… if she asks about her son, tell her he’s safe and not with her husband.”

“I’ll make a note,” he said. “Good luck, Ms. Alvarez.”

Luck had never played much of a role in my life. Preparation, maybe. Stubbornness, definitely. But I appreciated the sentiment.

On my way back to the station, the streets were finally picking up. People backing out of driveways, kids trudging toward school buses with backpacks swallowing their shoulders. A jogger in bright shoes, a delivery truck idling at a red light. Nobody looking at the brick building that housed the police department like anything important was happening inside.

In the squad room, Hernandez sat at his desk with two monitors glowing in front of him. One showed notes from his interview with Noah. The other cycled through still images from the gas station security cameras. On the screen, I could see a frozen Jack with the kid glued to his side, Ryan mid-step with that almost-smile.

“Got your update,” he said when he saw me. “Doctor thinks it’s a beating, not a stumble. They filed their report.”

“Neighbor sent pictures from last month,” I said, setting the printouts on his desk. “And texts. She had a bad feeling, tried to encourage Emma to leave. Emma said she couldn’t afford to. Classic isolation. No documented prior police calls from that address, though.”

“Of course not,” he said. “We only get called when it’s already the worst night of someone’s life.”

I tapped the gas station footage. “Have you watched the whole thing?”

“Twice,” he said. “Our unstable vet doesn’t look very unstable. He looks like a man trying hard not to make things worse while every alarm bell in his head rings at once.”

“Same read,” I said. “Noah mentioned him?”

Hernandez nodded. “Calls him ‘the soldier.’ Says he thought the soldier might not believe him either, but at least if the man got mad, he’d get mad at the right person.” He shook his head. “Nine years old, already calculating which adult is the safest bet for anger.”

“He picked well,” I said. “So far.”

We both knew that wasn’t always how those stories ended.

“I’m filing for an emergency protective order to keep Noah from going anywhere near Ryan,” I said. “Given the injury, the neighbor statement, and Noah’s disclosure, we have enough to justify it. He’ll need placement. Does his file list any relatives?”

Hernandez clicked through a few screens. “Maternal sister in another state,” he said. “Emergency contact on an old school form. No phone number, just an email.”

I wrote it down. Out-of-state placements were complicated, but if Emma woke up and wanted her boy with family, I wanted that path open.

As I turned to go, Hernandez stopped me. “One more thing,” he said. “We pulled some old call logs. Ryan’s name pops up a lot in community notes. Coaching, donations, committees. The kind of guy people vouch for without thinking. When this hits, there’s going to be pressure to treat it like a misunderstanding gone too far.”

I met his eyes. “Pressure from who?”

“From everyone who doesn’t want to believe they missed the signs,” he said. “From people who’d rather think the system did all it could, not that it turned away because the story made them uncomfortable.”

I thought about the stack of “inconclusive” reports in Noah’s file. There is a special kind of grief that comes from seeing how close we were, over and over, to drawing a different line.

“Then we build a case they can’t ignore,” I said. “One that holds up even when everyone in town wants to pretend this is new.”

Back at my desk, I opened my email and stared at the blank “to” field for a long moment before typing the address listed under “Aunt: emergency contact.” I kept the message simple: “Your sister has been injured. Your nephew is safe but cannot return home. Please call as soon as you receive this.”

I hovered over “send,” then clicked. Somewhere, a phone would buzz, and another life would tilt sideways because of what happened in that kitchen.

The last thing I did before the clock rolled fully into morning was open a new folder in our secure system and label it “MORRISON, EMMA – EVIDENCE, PERSONAL.” Into it, I dragged the neighbor’s photos, the hospital’s mandatory report, the gas station footage, and a placeholder for something I didn’t have yet but had a feeling I would.

Emma had been documenting, the officers said. Keeping her own record, hidden where she thought he wouldn’t look. Emails, photos, maybe even recordings. A private case file for a world that might one day believe her.

When I clicked on her name in the hospital intake, a small note popped up under “additional information”: “Patient mentioned draft emails to be sent ‘if anything ever happens to me.’ Location: personal account.”

I stared at the screen, heart thudding once, hard. Then I flagged it for a court order and leaned back in my chair. Somewhere on a server, a woman had written to the future, just in case tonight came.

When we finally read her words, they were either going to be the missing link that tied everything together—or a list of chances we’d all already had to keep this from happening.