Part 5 – Learning to Count

Dawn turned the parking lot the color of clean paper. A sign on the glass read, “Closed for Training—Opens at 9.” Inside, the lights were too honest and the air smelled like citrus cleaner and coffee someone loved enough to burn.

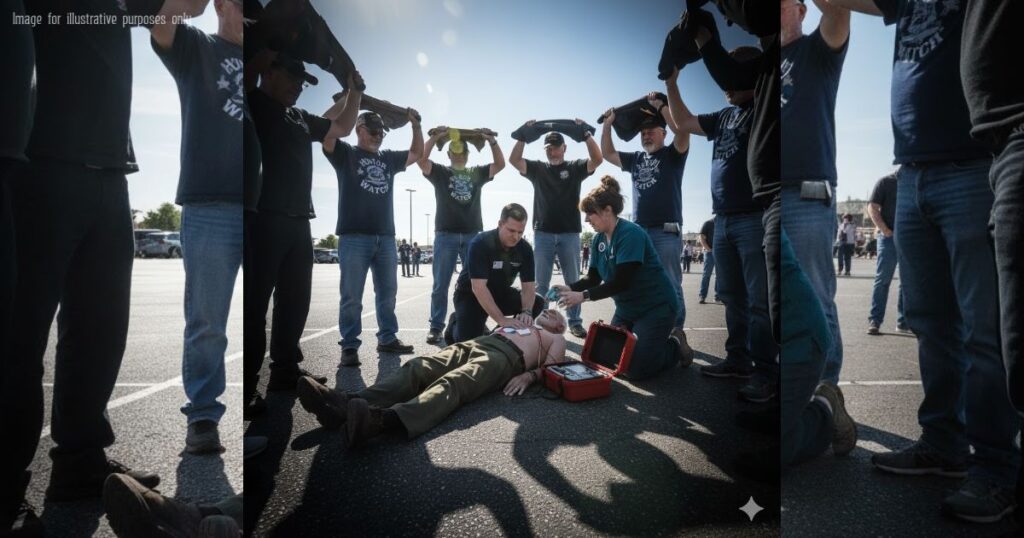

Mack rolled the manikin to Aisle Four and set an AED trainer on a lower shelf like it lived there. Ms. Alvarez clipped a radio to her belt and gathered the overnight and morning crews in a loose half circle. I passed out the simple cards: Check. Call. Compress. Shock. Continue.

“No filming,” Ms. Alvarez said gently. “This is about learning, not looking good.”

Ethan stood front row, sleeves pushed to his elbows. He looked like a person who had memorized a fire drill in a wooden house. He nodded at me once the way a runner nods at a starting pistol.

“We’ll run three scenarios,” I said. “Then we debrief like grownups. If you mess up, congratulate yourself—you found the part we fix.”

Scenario One started near the freezer cases where breath looks like ghosts. Mack collapsed the manikin smoothly, the way muscle memory knows drama without cruelty. Ethan knelt, tapped the shoulder, and said, “Sir, can you hear me?” His voice had volume without panic.

“Unresponsive,” I said. “Breathing?”

“Agonal,” he answered, listening right at the mouth, counting under his breath. “Not normal.”

“Call 911,” Ms. Alvarez told a cashier, pointing without shouting. “You—meet EMS at the door. You—fetch AED.”

A rookie reached for the manikin’s arm to drag it out of the way. Ethan put a hand up without scolding. “We’re good here,” he said. “No fire. No smoke. We stay.”

Compressions started. He counted steady and out loud, a rhythm borrowed from twelve calendar months, then cycling back: “January, February, March…” He watched the chest rise between each press, letting the plastic recoil do its job. When his arms trembled at twenty-eight, he said “switch” and a night stocker slid in without breaking tempo.

The AED arrived with a chirp that could wake a city pigeon. Pads on, everyone clear, analysis, then the machine that never takes sides delivered its sentence.

“Shock advised.”

Ethan scanned the arc of bodies. “Clear,” he said, not a question. He looked for hands touching shoulders, carts too close, fear hiding as helpfulness. He pressed the button. The manikin jerked in that small, theatrical way trainers do, and a cashier flinched at her own imagined guilt.

“Good,” I said. “Back on compressions.”

We ran the clock two minutes and then called it—ROSC in a drill is a nod, not a miracle. I blew the whistle I use when nerves keep talking after hearts are done. “Huddle,” I said.

Ms. Alvarez took notes with a grocery pencil. “Wins,” she said. “Then gaps.”

“Wins,” I counted. “Kept him inside, clear roles, loud counting, clean pads.”

“Gaps,” Mack added. “The AED cabinet alarm is loud; someone flinched and lost track for a beat. We’ll warn crews about the sound.”

A shy associate raised a hand. “I got stuck at thirteen,” she said. “My brain took a walk.”

“Mine does, too,” I said. “Tie numbers to anchors you already know—months, street names on your commute, your team’s batting order, whatever sticks. If you lose count, start again. Blood loves consistency more than perfection.”

We taped a tiny strip of blue on the floor to mark where the AED case shouldn’t be blocked again. The assistant manager updated the shift binder with the emergency map and a list of who calls whom. Someone brought over a rolling rack of privacy screens from seasonal and we parked them by customer service with a sign: For Medical Emergencies—Please Return.

Scenario Two was the front entrance—bad sightlines, door chime, people stacking in panic. We practiced how to make a human radius with carts turned sideways. We practiced saying, “Give us ten feet and your patience,” until the phrase grew natural and kind instead of bossy.

A little before eight, a knock came at the locked door. An older woman in a denim jacket held a paper sack the way saints hold candles. Ms. Alvarez motioned her in for a word and came back carrying the bag like history.

“From the food pantry,” she said, smiling. “She said Red used to bring her rice, and today she brought tamales.”

We leaned the bag on a breakroom table no checklist had planned for and pretended we didn’t ache at the symmetry. Training makes room for the unplanned if you let it.

Scenario Three was the nightmare: the self-checkout line, noise, beeping, kids, everything that makes a heartbeat harder to hear. We assigned a greeter to the front door for EMS, a runner for the AED, a privacy team, a caller, and compressions rotated like a relay.

Halfway through, the AED trainer refused to speak. A dead battery light blinked its quiet accusation.

“This is why we drill,” Ms. Alvarez said. She pulled the spare from the new emergency drawer, clicked it in, and the machine found its voice. Nobody cheered, but shoulders dropped the way relief makes them when small things work.

We debriefed on metal stools that had never hosted a more serious conversation. Wins: role clarity, speed, keeping the scene private and safe. Gaps: radio chatter stepping on commands, one aisle speaker too loud, the privacy screens need wheels.

“Order wheels,” Ms. Alvarez told facilities. “And extra gloves for the mask drawer. No shortages on the things that buy time.”

At 8:40 we gathered at Aisle Four as if it were a chapel. I held up the card with the five steps and then put it down on the shelf like we were leaving flowers.

“You did good work,” I said. “You’re allowed to feel that.”

Ethan looked at the manikin, then at his hands. “I didn’t lose fifteen,” he said. “I tied numbers to street names like you said. I got all the way to thirty with lungs left over.”

“Keep the lungs,” Mack said. “You’ll need them for the conversation upstairs.”

We walked into the morning like people who had already lifted something together. The hospital smelled like lemon and linen and second chances. Ethan counted his steps to the elevator doors and pressed the button like he was prepared to meet gravity as an equal.

Red was propped up, color back where faces live. He watched us enter with that thin, amused line his mouth made when he was trying to be braver than the tubes. His field jacket hung on the chair like history waiting its turn.

“Granddad,” Ethan said, the word standing awkwardly at first and then sitting down. “I read your letter. I checked under a plastic table and pretended it was wood.”

Red huffed a laugh that made the monitor draw a friendly hill. He reached for Ethan’s wrist with a hand that had taught rope and wrench and rifle and now wanted to teach softness.

“I was stone,” Red said, slow. “Thought stone was strong. Forgot water keeps people alive.”

Ethan nodded, eyes burning in the contained way of a grown man in a room with machines. “I was glass,” he answered. “Everything sounded like breaking.”

They didn’t hug yet. Sometimes that comes after the nouns agree. I pulled the chair closer and set a small kitchen timer on the bedside table like we were about to burn cookies instead of rewrite a winter.

“Teach him counting,” Red said, and the way he said it felt like handing over a family recipe. I set the timer for two minutes and placed Ethan’s hand over Red’s, palm to palm, that quiet CPR you do when life has already picked a rhythm but needs company.

“One,” I said, as the timer started. “Two. Three.”

They counted with me. They matched the monitor’s green heartbeat, not because it needed them, but because they needed it. At ten, Red’s eyes wet without apology; at twenty, Ethan’s shoulders dropped like wordless relief. At thirty, we paused and let the room be clean with silence.

“Again,” Red whispered.

We counted again.

Ms. Alvarez appeared in the doorway with a clipboard and a carton of that odd pink hospital lemonade. She waited until the second round finished and then spoke to Red the way people talk to a neighbor they didn’t know they’d care about.

“We’re putting the AED where folks can find it,” she said. “We have a map at every register. We’ll run night drills. We’re not moving anyone outside again unless the building is on fire.”

Red lifted a thumb a centimeter. That was enough.

“Tomorrow,” Ethan said, voice steadier than yesterday. “Another drill. Then I’ll come back. If you want me to bring the letter, I will. If you want to write me a new one, I’ll bring a pen.”

“Bring you,” Red said.

The physical therapist arrived with a rolling walker and a smile that said, Not yet, but soon. We stepped into the hall so Red could work without an audience. It is work, healing; nobody should pretend it’s a movie montage.

In the family lounge, Ethan studied the carpet pattern like it held answers. “I thought the hard part would be words,” he said. “It was feet. Making them go through a door.”

“Your feet told the truth before your mouth did,” I said. “That’s how most good stories start.”

He nodded and looked toward the elevators. “I’m scared of tomorrow,” he admitted. “Not of messing up. Of it not being a drill.”

“It won’t tell you before it arrives,” I said. “You won’t be ready in the movie sense. You’ll be ready in the muscle sense. That’s enough.”

On our way out, we passed a bulletin board with flyers—blood drive, meal train, a bright poster for “Community CPR—Sunday at 2 p.m.—Childcare Provided.” Someone had written “Spanish session added” in tidy pen and drawn a small heart that wasn’t corny because the ink believed itself.

My phone buzzed as the elevator doors opened. Ms. Alvarez’s name lit the screen. “Morning team wrapped,” her text read. “Afternoon crew at 1 p.m. Can you and Mack—”

Another text jumped in behind it from the store’s landline, flagged Urgent. “Customer down—front lanes—calling 911 now—AED en route.”

Ethan’s eyes met mine and went very calm, the way lakes do right before weather. He didn’t ask if we should run. He didn’t ask if we should pray. He pressed the elevator button for the lobby like a person hitting step one on a list he could finally say out loud.

“Check,” he said.

“Call,” I answered, already dialing.

We didn’t add the other words in the elevator because some prayers are better kept for the room where they’re needed. But they were there, lining up behind our teeth, ready to go the second the doors opened and the morning decided to test everything we had tried to make true.

Part 6 – When It Isn’t a Drill

The elevator doors opened like a held breath letting go. We moved through the lobby fast without looking frantic. Ethan’s voice was steady beside me, the list already lined up behind his teeth.

“I’ll take compressions,” he said. “You take airway. Ms. Alvarez will run the scene.”

The store was five minutes away if lights were kind. On the drive, she stayed on speaker, voice clipped and calm on radio channel three. “Customer down at front lanes,” she said. “Unresponsive, abnormal breathing. AED coming down. Greeter at door for EMS. Team A clears a ten-foot radius.”

We pulled up to a row of carts already turned sideways, forming a small, human room. A woman in a floral blouse lay on the tile with a coupon binder still open beneath her head like a pillow she never meant to use. A cashier knelt at her side counting, breath catching but voice loud.

“Twenty-six, twenty-seven, twenty-eight,” she said. “Switch.”

Ethan slid in at thirty without announcing himself like a hero. He locked his elbows, stacked his hands, and started pressing the way training had taught him to answer fear. “January, February, March,” he counted, voice low and even. The coupon binder slipped; a clerk whisked it away and tucked a folded jacket under the woman’s shoulders.

I dropped to my knees at her head, tilted her chin, watched the chest rise and fall in a way that wasn’t right. “Agonal,” I said. “Not snoring. Airway clear. Mask?”

“Mask,” Ms. Alvarez answered, already snapping on gloves and placing the pocket mask into my hand from the new drawer we’d labeled yesterday. She knelt where she could see everything and nothing blocked her decisions. “You,” she told a teenager with wide eyes and a soccer jersey, “stand by the door and flag the paramedics. You,” she told a shopper already holding her phone, “please lower your camera. We’re protecting her privacy.”

The shopper lowered the phone like it had gained gravity. Someone pulled the rolling privacy screens into place, two wheels squeaking like mice that didn’t want to help but would. The world narrowed to the radius of a life and the words we’d practiced into muscle.

The AED arrived with its new battery and its implacable tone. Pads on. “Analyzing rhythm,” the machine said, indifferent to our hope. “Do not touch the patient.”

Hands lifted. Ethan stared at the pads as if willing the universe to cooperate without bargaining.

“Shock advised.”

“Clear,” he said, scanning shoulders, fingers, carts, fear masquerading as help. “Clear, clear, clear.”

The button lit. He pressed it. The woman’s body jolted in that small, strange dance that looks like nothing and everything at once. “Resume compressions,” the machine said, and he did before the sentence ended.

I delivered two breaths with the mask, careful and slow, watching the chest rise like something remembering an old habit. “Keep going,” I said. “You’re on it. Twenty-five, twenty-six…”

Ms. Alvarez spoke to the room without raising her voice. “Thank you for your patience,” she told the onlookers. “We’re working. Please give us ten feet and your quiet.”

A toddler cried somewhere behind the screens, then stopped when his mother murmured a story into his hair. The store speakers cut off mid-song like even the Muzak knew when it should be silent.

“Two minutes,” I said, glancing at the wall clock we’d positioned on purpose. “Re-analyze.”

The machine agreed. “Analyzing rhythm. Do not touch the patient.” We lifted our hands and our hope at the same time.

“No shock advised,” it said. “Check for pulse.”

I slipped two fingers to the carotid, pressed gently into the soft just beyond the jaw. For a beat there was nothing but the sound of my own blood insisting. Then a flutter. Then something true.

“Pulse,” I said, too calm for what my chest felt. “Weak but there. Keep the airway open. O2 when EMS arrives.”

Ethan exhaled the way people do when they’ve been underwater on purpose. He didn’t look around for approval. He looked at the woman’s face as if memorizing it so he could keep counting for her later in his head.

The paramedics came through the human hallway with a stretcher and a rhythm already in their steps. The greeter guided them like a lighthouse wearing a name tag. Handoff went clean: age estimate, witnessed collapse, bystander CPR, one shock delivered, ROSC before transport. The medic nodded as if we had laid out tools in the right order on a tray.

“Nice work,” he said, and meant it like a handshake.

As they lifted her, a small zippered pouch slid out from under the coupon binder. The paramedic caught it with a practice born of repetition and handed it to Ms. Alvarez without ceremony. She opened it, saw a medical alert card and a list of medications, and slid it into the EMS bag like a note tucked into a lunchbox.

When they were gone, the room got loud again the way rooms do when purpose leaves and air rushes in to fill the hole. Someone cried because they had been brave. Someone else laughed because their hands were still shaking and laughter sometimes trips on its way to relief.

We debriefed before the floor could return to normal and pretend it had always been. Wins: roles held, counting loud, radius held, camera down, AED functional. Gaps: one cart too close, mask drawer needs a small sign, privacy screens still squeak.

Ethan leaned against a column and let his hands hang like he wasn’t sure who they belonged to. He met my eyes the way people check their work with the teacher who will tell them the truth without taking their lunch. “I didn’t lose fifteen,” he said. “I got to thirty and back again.”

“You did more than count,” I said. “You made a room.”

He glanced at Ms. Alvarez, who was writing action items like a coach diagramming victory without gloating. “We’ll run it again tomorrow,” she said. “Different lanes. Different greeter. Same quiet.”

The woman’s coupon binder lay open on the floor. A clerk knelt to gather the paper coupons with the kind of care you give to someone’s life when you understand it’s not yours. He slid the binder into a plastic bag with her purse and a note: Return to patient when appropriate.

We took down the screens and turned the carts back into aisles. We threw away the used mask and snapped a fresh one into the drawer. We wiped the AED pads tray and closed the lid with gratitude and a gentle hand.

Outside, the heat had lost its edge. We stood under the lip of the roof and let the shade say we’d earned a minute. Mack arrived at a jog, late only by the measure of adrenaline, not of service. He looked at the door where the stretcher had been and then at Ethan.

“You were here,” he said.

“I was,” Ethan answered, no apology chasing the words.

Mack clapped his shoulder without making a ceremony of it. “Good,” he said. “Now go upstairs.”

We drove in a line back to the place where the monitors draw hills and the coffee always tastes like relief. In the elevator, Ethan didn’t speak. He pressed his palms together like a person who has just learned his hands can say sentences.

Red was sitting up when we came in, the field jacket on the chair, the three-word scrap of nutrition label on the tray. The room smelled like lemon and something else—closer to hope than to bleach. He watched Ethan cross the threshold and raised his eyebrows like a question that already knew the answer.

“We ran the drill,” Ethan said. He didn’t try to make it grand. “Then it wasn’t a drill. We did what you taught us.”

Red’s mouth pulled toward a grin that had years in it. He patted the bed rail. Ethan stepped closer. I set the small kitchen timer on the table again like a habit turning into a ritual.

“Tell me,” Red said.

Ethan did. Not the glory parts. The small parts that make a thing workable. The carts sideways. The kid at the door. The camera down. The squeaky wheels. The woman’s binder like a wallet of weekday miracles. He counted under his breath once without noticing—January through June—like he had split his heart into months and found them all right where he left them.

When he finished, Red closed his eyes for a second the way people do when their chest fills faster than their lungs. He reached for Ethan’s wrist, then his hand, then finally the space between them as if measuring a distance that had become negotiable.

“Good,” he said. “Again tomorrow.”

“Again tomorrow,” Ethan echoed.

The physical therapist came to walk Red to the door and back, a pilgrimage measured in tiles. We stepped out so the room could be the size he needed it to be. In the hall, a volunteer taped up a flyer for the afternoon CPR class with a small correction in pen—Spanish session added—and the world tipped slightly toward better.

My phone buzzed with a message from the paramedics. “Patient stable, en route to cath lab,” it read. “Please thank your team.”

I showed it to Ethan. He read it like it was a letter from a winter he had survived. He leaned against the wall and let his head tip back, a quiet laugh escaping like steam from a kettle you forgot was on because it wasn’t screaming anymore.

“What now?” he asked, not because he needed a plan but because plans keep some people standing.

“Now you eat something,” I said. “Then you sit with your grandfather while he works harder than any of us did today.”

He nodded. He looked at his hands again, palms open. “They feel heavier,” he said.

“They’re full,” I said. “That’s different.”

We went back in when Red signaled with a chin lift and a smirk. The timer sat ready for another two minutes if needed. The jacket waited on the chair like a story that would keep. The day felt like it had run toward us and then decided to walk at our pace for a while.

By evening, the community page had a new post. Not a shaky clip. A photo of the AED cabinet with a caption that said, “If you’re wondering whether to learn this, yes.” Three lines down, a comment from someone with a floral blouse in their profile picture read, “Thank you for counting when I couldn’t.”

I clicked the little heart because it was the only button that made sense. Then I set an alarm for tomorrow’s early training and wrote one more note for the whiteboard at the center.

“See the person. Make the room. Count out loud.”