Part 9 – Hang the Jacket

Morning came in clear and ordinary, the way big days like to pretend they aren’t.

We signed out Red’s field jacket from the nurse’s station with clean hands and a promise to bring it back before lunch.

“Hang the jacket first,” Red said, voice rough but playful. “Then hang the rules.”

He pressed a pen into my palm and tapped the blank side of a discharge instruction sheet. “Write this for the plaque: See the person. Make the room. Count out loud.”

We drove to the store before opening.

Ms. Alvarez had a small team waiting by a corkboard they’d bolted to a support column near the entrance.

The header said “Community Wall”—plain black letters on white, no exclamation points.

Under it waited three empty frames, a shelf for index cards and markers, and a space big enough for the jacket to look used, not staged.

Ethan stood very still, then put on nitrile gloves like a ritual.

He lifted the jacket the way you carry something that used to be a person’s armor and is now a town’s lesson.

We mounted it on two sturdy pegs.

No glass. No lock. Just weight and wood and a little gravity.

Underneath, I screwed in a simple aluminum strip with etched words:

SEE THE PERSON. MAKE THE ROOM. COUNT OUT LOUD.

Below that, the five steps on a small card in English and Spanish: Check. Call. Compress. Shock. Continue. / Verifique. Llame. Comprimir. Descarga. Continúe.

Ethan stared at the plate like it might blink.

“Will he like it?” he asked, voice smaller than his shoulders.

“He wrote it,” I said. “He’ll see himself.”

A woman in a floral blouse came in with her cousin and a shy smile that carried a few thousand thanks.

She touched the jacket sleeve with two fingers, then pinned an index card to the corkboard.

“Thank you for counting when I couldn’t,” the card read. “I keep coupons because money is tight. You kept breath because life is.”

Someone exhaled the way you do when the right words find the right wall.

A clerk added a photo of the AED cabinet with the caption, “If you’re wondering whether to learn this—yes.”

Ms. Alvarez set a box of index cards and pens on the shelf.

“No names required,” she said. “Just verbs.”

By nine, the first wave of customers came in curious and careful.

They slowed. They read. A few took photos, then put their phones down to write.

A teenage bagger pinned up his note next:

“I used to freeze. Now I count.”

He drew a tiny metronome that looked like a house.

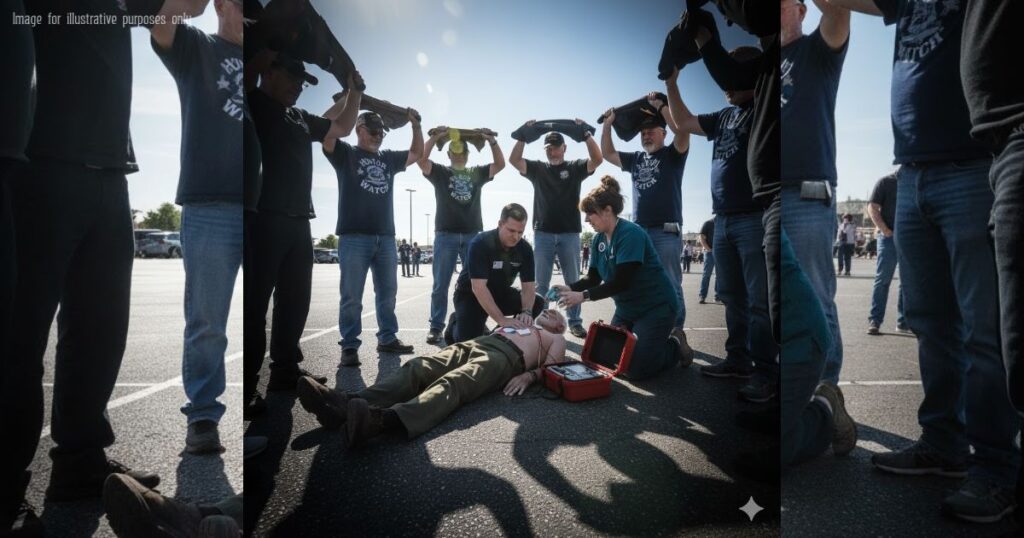

We rolled a portable screen beside the column and scheduled mini-demos every hour on the hour.

Two minutes, no gore, all steps. Anyone could step in and try a compression.

Ethan led the first one, palms steady, voice even.

He counted January to June, switched, then July to December, smiling when a shy kid mouthed the months along with him from the stroller bar.

At ten-thirty we FaceTimed the hospital.

Red filled the screen in that way hospital cameras do—too close, too honest—but his eyes were bright.

“We hung it,” Ethan said, and stepped back so Red could see the jacket, the plaque, the cards blooming on cork.

Red’s hand rose, a centimeter, approval and ache in one small motion.

“Looks used,” he said, satisfied. “Leave it that way.”

“People are writing,” I told him. “Short and true.”

“Good,” he said. “Stories teach where speeches don’t.”

We signed off so respiratory could do their rounds.

Ethan didn’t move for a second after the screen went dark, as if staying still would keep the moment from ending.

Mack arrived with a shoebox and an inside joke for no one.

He set it on the counter and tipped it open: laminated “Check. Call. Compress. Shock. Continue.” cards, a handful of pocket masks, and a small, plain patch that said Volunteer.

He handed the patch to Ethan without ceremony.

“No vest,” Mack said. “Just a patch. It goes on whatever you wear when you show up.”

Ethan took it like a passport.

He didn’t put it on yet. He just held it, as if measuring the weight of earning versus wearing.

At lunch, Mr. Rodriguez shuffled in with a walker and a stubborn grin.

He held out a coin between thumb and finger, a nickel polished by years and pockets.

“For your wall,” he said to Ethan. “I taped one under my table in ‘79 for luck. Luck works better when people knock on your door. Tape this where you can find it when you forget.”

Ethan smiled so fast it looked like a stumble.

He slid the nickel under the bottom edge of the plaque and pressed a square of blue painter’s tape over it like a quiet oath.

In the afternoon we went to the community center for the bedside drill.

Red wanted to teach from where he was, and the nurse—smiling, practical—said yes if we kept it gentle.

We set the iPad on a stand so a half-dozen trainees could see the monitor.

Red lifted a finger in greeting, then pointed at his wristband as a prompt.

“Read the bracelet,” he said. “Ask before you guess. Pocket left, nitro. Don’t drag a man into the sun to make him less your problem.”

We counted with his monitor for two minutes—

a class of strangers syncing breath to a green line, letting a machine keep time while humans learned to keep promises.

When we finished, Red blinked and smiled the smallest smile machines can’t detect.

“Again tomorrow,” he said, and the nurse rolled her eyes lovingly like only nurses can.

Evening brought a softness you can’t buy.

The gym wound down. The generator fell silent. People carried cots back to the closet and folded hope carefully so it wouldn’t wrinkle before the next storm.

At the store, Ms. Alvarez unveiled the second part of the wall: a simple calendar for classes, lines already filling with first names and pen dents.

“We’ll comp employee classes,” she said. “And set aside ten seats per session for the public. If we run out, we add chairs.”

A reporter stopped by again; she photographed the nickel without asking and then asked.

“What’s with the tape?” she said, pen ready.

“Luck needs help,” Ethan said. “Tape is help.”

She laughed and wrote that down verbatim.

Sometimes the best quotes are made of glue.

We closed the day with one last demo by the wall.

A grandmother tried compressions with rings she refused to remove because they were married to her hands; a teen counted for her so she could focus on depth.

“Good,” I said. “Switch at twenty-eight if your arms tire. No heroes who forget to rotate.”

After the crowd thinned, Ethan and I stood in front of the wall and pretended we were customers walking in tomorrow for the first time.

We looked where their eyes would land. We fixed a crooked card. We added a pen where a pen would be reached for.

My phone buzzed with a message from the charge nurse.

He walked farther today. If numbers look this good in the morning, he can have a thirty-minute day pass with an escort. He asked if ‘escort’ can be the kid.

I showed Ethan. He didn’t answer right away.

He nodded, then exhaled like someone stepping into a river to see if it’s cold.

“We’ll bring him to see the wall,” he said. “He’ll hate the fuss.”

“He’ll love the verbs,” I said.

Ms. Alvarez came over with a small wooden frame.

Inside, printed on plain paper, sat the sentence Red had dictated and the five steps, English and Spanish, in a font nobody would notice because it behaved.

“We’ll mount this under the jacket,” she said. “And tomorrow morning, if he’s cleared, we’ll take a photo of his hand pointing to nothing but the words. No names. No halo.”

“Good,” I said. “Make the words the hero.”

We returned the jacket to the hospital for the night, leaving the pegs bare like a reserved seat.

Red touched the empty space on the video call and smirked. “You better bring it back,” he said. “Jackets run off if you don’t tie them down with promises.”

“We tied it with tape,” Ethan said. “And a nickel.”

Red coughed a laugh. “Good,” he said. “Tape beats hope when hope gets slippery.”

The hospital quieted in that particular way it does when the night shift owns the hall.

We set the jacket on the chair again, sleeve folded under like a sleeping hand.

“Tomorrow,” Red said, closing his eyes. “Fifteen minutes. That wall. Then back. Not a parade—a visit.”

“Deal,” Ethan said. “I’ll count the steps so you don’t have to.”

We stepped into the corridor, lighter by one fear and heavier by one plan.

Mack texted a photo of the gym, dark now, with three phrases chalked on a portable board for the morning class: See the person. Make the room. Count out loud.

He added, Add: “Teach the next pair of hands.”

I wrote it down to argue with later and immediately knew I’d lose the argument.

At dawn we’d bring the jacket back, hang it straight, and wait for a heart rate and a doctor’s signature to agree.

At noon, if the weather and mercy held, Red would stand under his own story and point at the part where it stopped being his alone.

We walked toward the elevator.

The overhead lights flickered once and steadied, just nerves in the wiring.

My phone buzzed again—Ms. Alvarez, this time with a calendar screenshot.

Community Class, Saturday 12 p.m.—parking lot, tents, shade, water. Media optional. Everyone else necessary.

I sent a thumbs-up, then added, We’ll bring him if cleared.

We reached the lobby just as the store’s landline lit my screen with a text relay from the radio.

Three words, all verbs, nothing fancy:

Medical emergency—entrance.

The second message stacked under it like a metronome finding tempo:

AED en route.

Part 10 – See the Person, Make the Room

The radio clipped the words into place before fear could.

“Medical emergency—entrance,” Ms. Alvarez repeated, already moving. “AED en route.” We were out the door before the second tone finished telling us we were needed.

A man in his fifties was on the mat between the sliding doors, half-in and half-out of the conditioned air.

Heat pressed one side of his face while the AC argued with the other. Two shoppers hovered, hands full of concern and nothing useful to do with it.

“Inside,” I said, firm but calm. “He stays inside unless the building is unsafe.” Ethan angled two carts sideways to make a room and waved the greeter to hold one door wide so air wouldn’t stutter the scene.

We tapped shoulders and asked for response.

His breathing was wrong in the way training teaches you to recognize without panic. Ethan dropped to his knees and found rhythm like an address he knew by heart.

“January, February, March,” he counted, compressions two inches deep with full recoil. I squeezed the pocket mask, two measured breaths, then watched his chest rise like a stubborn engine finding fuel.

The AED arrived with its new battery and old authority.

Pads on, hands up, the machine listened the way you want a machine to listen. “Shock advised,” it said, efficient and indifferent to our hope.

“Clear,” Ethan called, eyes scanning for stray hands and moving feet. He pressed the button and the man’s body lifted a fraction, a single quiet thunder under our palms. “Resume compressions,” the device said, and we did without asking permission from fear.

Ms. Alvarez worked the crowd without sounding like a bouncer.

“Give us ten feet and your quiet,” she said, privacy screens gliding in on newly silent wheels. The greeter flagged EMS outside and held the door like a person holding a promise.

Two minutes passed on the wall clock we had placed on purpose.

“Analyzing rhythm,” the machine intoned, and we lifted hands as if the floor had turned to glass. “No shock advised. Check for pulse.”

I pressed fingers into the soft space beside his jaw and held my own breath still.

Something fluttered under my fingertips and gathered itself into a small conviction. “Pulse,” I said, and Ethan sat back on his heels without breaking eye contact with the man he had just convinced to stay.

Paramedics took over with that respectful speed trained people give one another.

Handoff was clean: witnessed collapse, bystander CPR, one shock delivered, ROSC before transport. The medic glanced up and tipped his chin, a thank-you too busy to make a speech.

We debriefed while the entrance remembered how to be an entrance.

Wins: kept him inside, roles held, counting steady, AED functional. Gaps: the mat had curled at the edge; facilities taped it down within the hour and wrote a work order for a safer one.

By late morning, the call we had waited for arrived.

“Thirty-minute day pass approved,” the nurse said. “Escort requested: the kid.” Ethan stared at his phone like it had spoken a second language he suddenly understood.

We signed out the field jacket with clean hands and steadier hearts.

Red met us at the curb in a wheelchair, color better, eyes clear enough to hold more than one feeling. He nodded at Ethan, then at the jacket, then at the world that seemed ready to behave.

At the store, we wheeled him straight to the Community Wall.

The jacket hung there without glass, weight honest, sleeves telling their quiet story. Under it, the nickel sat taped beneath the plaque like a secret you were meant to find.

People stepped back without being told.

Red lifted his hand and touched the edge of the aluminum words. “See the person. Make the room. Count out loud,” he read, the cadence of someone reciting inventory and prayer at the same time.

A grandmother asked if she could try compressions for exactly two minutes.

Red nodded, and Ethan knelt beside her, counting months while she pressed, then thanking her like she had donated something rare. “Switch at twenty-eight if your arms tire,” he said, and she laughed because generosity is heavy and still worth carrying.

Ms. Alvarez brought a small frame for the bottom of the wall.

Inside were the five steps in English and Spanish, printed simple so nobody had to wrestle with fonts. “No heroes who forget to rotate,” she added, smiling at Red like they shared a conspiracy that favored competence over drama.

Mack arrived with a plain canvas armband that said Trainer in block letters.

He offered it without ceremony. “If you want it,” he said, “wear it when you’re teaching. If you don’t, hand it to someone who will.”

Ethan looked at Red before answering, and Red looked at the way Ethan looked.

“Wear it,” Red said. “Then pass it when you find someone whose hands are ready.”

We took a photo with permission and without spectacle.

No names on a banner, no halo edits, just a hand pointing to the verbs and a town that had decided verbs were enough. The reporter from the local paper stood back and waited until we nodded before she lifted her camera.

Outside under pop-up tents, the community class filled every folding chair.

Shade pooled under canvases. Water jugs sweated in buckets. A sign read “Media optional. Everyone else necessary,” and it felt more like a guideline than a joke.

We taught check, call, compress, shock, continue until the words behaved like muscle.

People counted by months and ball teams and street names and songs they could hum without thinking. The AED trainer said its lines over and over until nobody in the parking lot flinched when it spoke.

Midway through, a teenage bagger with shy eyes and a metronome doodle pinned to his shirt stepped forward.

“Can I lead one?” he asked, voice small and brave at the same time. Ethan set the pace with a nod and the kid counted clean to thirty, then back again, switching at twenty-eight without losing the room.

Red watched from his chair with his field jacket over his lap like a mantle that had chosen warmth over hardness.

He lifted two fingers when the teen finished and said, “Good,” which is a word that can build a hallway if you let it.

When a summer gust shoved at the tents, we put hands to poles and kept the shade where we had promised it would be.

When a phone rang with something private, the owner stepped away and took the news without making it the class’s problem. When a child asked if thunder could see her, her mother said, “No,” and then taught her to count it anyway.

Time did that elastic thing it does when you are useful.

Half an hour stretched, then snapped, then returned without apology. The nurse checked her watch and tapped Red’s shoulder with a grin that meant rules and mercy had agreed to a draw.

We wheeled him back through the entrance that had learned to be a threshold and not a hurdle.

He stopped us once and pointed at the curled mat now taped flush to the tile. “Fix the small things before they trip big moments,” he said, and Ms. Alvarez made a note even though the tape already gleamed.

In the room that had been our small country for a few days, Red lay back with the careful sigh of a person who knows the work is both over and still happening.

He handed Ethan the envelope labeled “Kitchen—Winter—Loud,” now folded again along softer lines. “Burn it or keep it,” he said. “But write a new one.”

Ethan set the plain canvas armband and the letter side by side on the tray.

“I’ll keep both close,” he said. “And pass one on when the next pair of hands shows up.”

We counted with the monitor one last time, not because the machine needed it, but because we did.

At ten, Red’s mouth tugged up the way it does when a pain has decided it will not be the final author. At thirty, we let the room get quiet and let that be the skill for once.

Before evening, the community page posted a photo of the wall.

No faces, just the jacket, the nickel, the verbs, and three hands—one older, one younger, one small—pinning a new class time to the cork. The caption read, “We don’t guess. We ask. Then we count.”

The comments did what comments do, but something had shifted.

Fewer arguments about yesterday. More questions about Saturday at noon. A link to Spanish sessions. A note from the woman with the floral blouse: “Home now. Breathing. Practicing counting to sleep.”

On my way out, I stopped at the wall and straightened a card someone had pinned at an angle.

It was from the shy teen who had led compressions. “I thought courage was loud,” it said. “Turns out it’s steady.”

I walked to the exit and looked back once because people do that when they are leaving a place that kept its promises.

The jacket didn’t look holy. It looked used. The plaque didn’t shout. It told the truth and let the verbs be bigger than any single name.

At home, my daughter asked if thunder could count by twos.

We tried it and laughed when it worked exactly as well as counting by ones. I added a card to our fridge under the crayon AED that read, “Teach the next pair of hands,” and she asked if that meant hers.

“Yes,” I said. “Especially yours.”

Later, I stood at the sink and let the day rinse from my fingers.

In the mirror I looked like a person who had been held up by a town, and under the tired I could see the small bright line that shows up when a plan on paper gets fingerprints.

If you need a moral, it isn’t complicated enough to hide behind.

See the person. Make the room. Count out loud. Teach the next pair of hands. Don’t guess when asking would save someone you love.

Tomorrow there will be another class, another cart to turn sideways, another mat edge to tape before it trips somebody.

Tomorrow someone will walk in wearing something that confuses you, and you will pause long enough to ask a better first question.

Red will heal because bodies can surprise you when communities keep their part.

Ethan will teach because repentance that turns into service is the kind that lasts. And the wall will collect verbs until the cork has to be replaced, which is exactly the sort of maintenance a town should be proud to perform.

When you tell this story to someone who wasn’t there, don’t make anyone bigger than the verbs.

We are not our jackets or our titles or our worst day at a sliding door. We are what we do with our hands when the machine says, “Shock advised,” and what we teach after the pulse returns.

If you’re wondering whether to learn this—yes.

If you’re wondering whether you’re the kind of person who should show up—also yes. And if you forget the steps when fear gets loud, look for the nearest wall and the nearest human, and start with the only three words we kept testing until they stayed.

See the person.

Make the room.

Count out loud.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta