Part 1 — The 1:07 Call

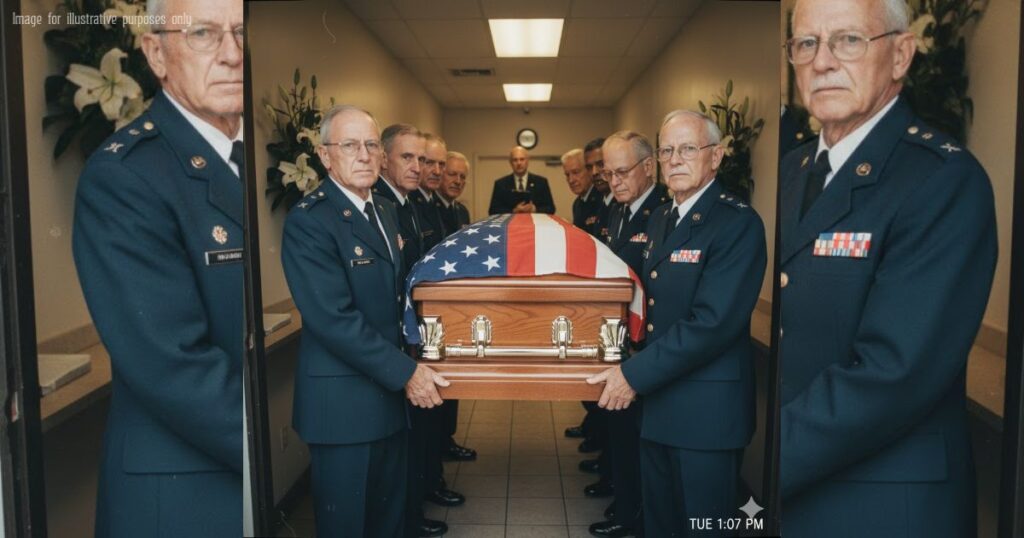

Tuesday at 1:07 p.m., seventy-one veterans lined up in faded dress uniforms to carry a woman none of us had ever met.

That sentence shouldn’t exist. It flashed across my mind the second the phone rang in our tiny office above the community center, the place where we meet on Thursdays to swap stories and keep one another steady. I’m Cal Rivera. I don’t scare easy, but the voice on the line made me grip the desk.

“She has no one,” the funeral director said. “Her name is Lieutenant Maya Torres. Combat medic. She died last week in a veterans hospital. No next of kin on record. By the book, we cremate tomorrow morning. No service.”

No service. No flag. No names spoken out loud. Just an intake number and a date.

I looked at the glass case on the wall where the folded triangle of my father’s flag sits, the linen softened by time and fingerprints. A folded flag with no hands to receive it is a grief I can’t swallow. It’s a door locked from the outside.

“We’ll be there,” I said before I’d figured out the details. “Tell me when and where.”

“You don’t even know her,” she whispered, as if we might change our minds if we stopped to think.

“She wore the uniform,” I told her. “That makes her ours.”

I sent the first text at 1:12 p.m. to our little volunteer network of former service members—Valor Circle, just neighbors with a group chat and a promise. Unclaimed medic. Service tomorrow. We stand watch. I hit send and stared at the typing bubbles that popped up like flares in the dark.

The replies came hot and brief, like radio checks in a storm.

On my way.

Two from across town.

I can bring a bugle.

My dress blues still fit, sort of.

Got a spare suit for the kid who grew out of his last one.

At 2:00, the funeral director called back, voice shaking. “How many people did you invite?”

“I asked whoever still believes in showing up,” I said.

She lowered her voice. “There are already motorcycles and sedans lining the block. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“This isn’t a protest,” I told her. “It’s a promise.”

The rest of the day ran on muscle memory. I printed programs with a simple line: Maya Torres — Daughter, Healer, Soldier. No dates yet; we hadn’t found them. Just the name and the word Healer in the middle, because even in death a healer ought to be called what she is.

We cleaned the spare honor rifles we use for memorial volleys when families ask us. We checked with the funeral home about the order of service. We kept it simple: a moment of silence, a short prayer if the room wanted it, a reading, the fold and presentation of the flag. The question that kept circling the table was the one no one wanted to voice out loud.

Who do you hand the flag to when there’s no one left?

By evening, the group chat had turned into a chain of arrival times and rough travel plans. Two retired medics were driving through the night. A young private who’d been discharged after an injury sent a photo of his battered dress cap with the caption, It’s wrinkled, but I’m coming anyway. A widow asked if she could bring a plate of cookies. Someone else offered coffee. Someone offered tissues. Someone else just posted the words, Standing by, because sometimes that’s all a person can promise.

At sunrise the next day, I parked three blocks from the funeral home because the street was already thick with cars. Men and women I’d never met shook my hand like old friends. Some wore suits that had seen better days; some wore jackets with unit patches sewn on crooked but proud. A toddler held his grandfather’s elbow. A woman with gray hair tucked a small bouquet of wildflowers into the crook of her arm like she was carrying a secret.

Inside, the room was plain: polished wood, pale walls, a single arrangement of lilies that made the air smell like Sunday morning. The casket sat open for a while, then closed by quiet request. I stood at the front and told them what I knew, which wasn’t much: that Maya had served as a medic overseas, that we didn’t have a full record yet, that her name deserved to echo more than once.

I asked for a minute of silence. The kind that isn’t empty but full—full of names, of dust, of an old cadence that never really leaves your bones.

When the minute ended, a volunteer read a psalm. A former chaplain offered a short prayer for the living. We came to the part we always come to: the folded flag, the question mark of it. I looked out over the room, at the faces that had driven across counties and state lines to sit with a stranger for an hour, and thought: This is what family looks like when you strip away everything but love and duty.

I was about to close the service with a single sentence—“Thank you for showing up”—when a cane tapped the tile in the back row. Deliberate. Steady.

An older man rose, his suit hanging loose on a frame that hadn’t been fed by sleep in a while. He held a photograph in a trembling hand, the corners frayed, the image faint beneath a veil of dust that no amount of time could shake loose.

“I knew her,” he said, and the room stilled the way a field stills when rain finally starts. “Diyala Province, 2007. I was bleeding out in a ditch. She crossed open ground to get to me. Wrapped my leg with a strip of her own shirt and talked me through the pain like she had all the time in the world.”

He swallowed, eyes bright. “I have carried this picture for sixteen years. And I think I know why her daughter isn’t here.”

The cane tapped once more. He lifted the photo so the light caught it.

And every breath in the room seemed to wait for what he would say next.

Part 2 — The Blurred Photograph

He didn’t hurry. He didn’t need to. The cane tapped once, then he lifted the picture high enough for the light to catch the grit ground into its surface.

“Diyala Province, 2007,” he said. “Convoy hit a choke point. Everything got loud at once.”

The room leaned forward without moving. He didn’t give us every detail—he didn’t have to. Those of us who’ve been there can fill in the blanks: the metallic taste of fear, the sand that gets under your eyelids and never leaves, the way time stretches and then snaps.

“I went down hard,” he continued, voice steady but frayed at the edges. “Couldn’t feel my leg. Dust everywhere. I remember thinking, ‘If I close my eyes, maybe I can sleep through this.’ Then she was there. Crossed open ground like the laws of gravity didn’t apply to her. Said her name was Torres. Said, ‘Stay with me. I’m not in the mood to carry you.’ Then she carried me anyway.”

A few people laughed—quiet, grateful, the kind of laugh you make when a story gives you room to breathe.

He took a step closer, cane ringing lightly on the tile. “She ripped a strip from her own shirt, wrapped me tight, and started talking. Not about war. About my sister’s second-hand bicycle, which I’d mentioned ten minutes earlier like an idiot. She remembered. She made me remember. She walked me through the pain until the bird came. Then she went right back out, because there were others.”

He turned the photo so we could see. The image was half-shadowed, a figure in a sun-bleached uniform, a medical bag thumping against her hip, hair tucked under her cover. The name tape was just visible if you knew what to look for: TORRES. She was angled forward the way people move when they have decided the only way out is through.

“I’ve carried this picture for sixteen years,” he said. “I kept it in my wallet until it started to fall apart. Sometimes I set it on the nightstand to remind myself how to be brave. I tried to find her once. Visited the hospital where someone said she’d been working nights.” He glanced down, a small smile cutting through the heaviness. “I tried to thank her. She wouldn’t let me. She just said, ‘If you really want to help me, go sit with that young soldier over there until he falls asleep.’”

The woman with the wildflowers made a small sound, part laugh, part sob. I felt it in my ribs.

“She kept a list,” he went on. “Spiral notebook. Front page said, ‘Call me if you can’t sleep.’ Numbers and first names, some with stars, some with little notes like ‘ask about the dog’ or ‘tell him to eat.’ I recognized a few of the names. I realized I wasn’t the only one she’d dragged back from the edge.”

He looked over the rows of faces and finally gave us his own. “My name is Jonah Park,” he said. “I walked back into my life because of her. Got married. Helped coach a little league team, badly. I wanted to bring her flowers one day. I stopped by around fall a few years back. Saw her sitting in her car on the far side of the lot, phone to her ear, staring at the moon like it was a clock. She was talking to a kid whose voice was shaking. She missed something that night. A celebration—maybe a family thing. She said, ‘I’ll be late,’ and didn’t explain. She chose that call.”

He swallowed, the line of his throat working. “I don’t know her daughter. I would never speak for anybody’s grief. But I’ve seen enough to guess. Sometimes, the people who do the most good look like they’re choosing strangers over their own. What they’re really choosing is the fire alarm that’s ringing in somebody else’s kitchen.”

Silence doesn’t always mean emptiness. Sometimes it means a room is collecting pieces of itself so it can hold what comes next. I looked down at the front row. A teenager gripped a program between white knuckles. A man with a high-and-tight cut his own hair with clippers still in the drawer at home; his hand flexed once, relaxed.

I cleared my throat. “Jonah, thank you,” I said. “If you’re willing, we’d like to make a copy of that photo. Put it where people can see the kind of courage that walks into a room and pretends it’s just another Tuesday.”

He nodded and eased the picture into my hands like it was something that could break the floor if dropped. I held it carefully, reading in the scratches all the times it had been taken out, shown, put away, taken out again on nights that needed proof.

The funeral director touched my elbow and slipped me a small envelope. “Her personal effects,” she whispered. “No next of kin on the paperwork. We’ve been holding onto them.”

I stepped to the side and opened it. Inside: a few coins. A folded appointment card from a clinic office with a date six weeks ago—Peer Support Orientation scrawled across the top, time underlined twice. A plain index card, creased and soft at the corners. On one side: a list of first names and numbers written in a medic’s quick block letters. On the other: a sentence in all caps.

IF IT’S MIDNIGHT AND YOU’RE ALONE, CALL ME.

IF IT’S 3 A.M., CALL TWICE.

I showed the card to the funeral director. She pressed her lips together hard, the way people do when tears start before they’re ready.

“Can I read something?” I asked the room.

Heads nodded, a wave you could almost hear.

I read the sentence out loud the way I imagined she would—no drama, just directive. A few people in the back pulled out phones like muscle memory had taken over, typing in a number that no longer connected to a person but still connected to a purpose.

Jonah sat down slowly. His hand found the back of the chair in front of him; the man in that chair reached back without turning and squeezed once.

A retired nurse stood, the kind who could stare down a hurricane. She lifted her chin, meeting the eyes of strangers and not finding strangers there. “I worked nights on the same ward,” she said. “I can vouch for what Jonah just said. She made rounds with her lunch untouched. Brought an extra sweater in case somebody was cold. Took the calls no one else had time to take. She argued with the vending machine on behalf of kids who didn’t remember to eat until midnight. And when I told her she needed to rest, she said, ‘Rest is for when the fire’s out.’”

A ripple of warmth moved through the room—pride mixed with something like ache.

A man in a suit jacket with old unit pins along the lapel lifted a hand but didn’t speak. Sometimes you don’t have the words. Sometimes the words would get in the way.

“You asked earlier,” the nurse said to me, her voice softening, “who to give the flag to.” She looked around the room and then up at the closed casket. “We’ll figure it out. That’s what people like her taught us.”

I nodded, throat tight. “We will.”

My phone buzzed against my palm. So did hers. So did the bugler’s, the usher’s, three people near the door. The funeral director glanced at her screen and went pale in the way that doesn’t mean fear so much as escalation.

She crossed the front of the room with quiet steps and leaned toward me just enough that I could feel the chill of the paper she pressed into my hand. It wasn’t paper. It was the knowledge that a moment was about to turn.

“They’re here,” she whispered. “Family. They’re asking to take her now.”

The word family can lift or crush depending on what comes after it.

I looked toward the entryway—toward the corridor where the light ran thin and the air changed temperature—and felt the room inhale as one.

“Folks,” I said, voice steady because a steady voice is a kind of flag, “we’re going to pause a moment.”

Jonah’s cane tapped once more. The bugler lowered his instrument. The nurse folded her hands. Somewhere in the back, a child stopped fidgeting and went still as a photograph.

The funeral home door eased open. Footsteps. A hush that wasn’t empty at all.

And then I saw them stepping through the threshold—faces shaped a lot like the one in that grainy picture I still held—bringing with them a wind that could either put out fires or feed them.

Part 3 — Those Who Share a Name

They paused at the threshold like people stepping into cold water. The young woman’s jaw set first, not her feet. The man beside her carried himself like he’d learned to be steady for other people a long time ago.

The funeral director met them halfway, palms open. “Thank you for coming,” she said, voice low. “We’re in the middle of a service. We can pause to speak privately, or—”

“We’re here for our mother,” the woman said. She didn’t look angry so much as out of breath from a sprint no one could see. “I’m Ava. This is my uncle, Lucas. We want to take her with us. Today.”

The room had already heard the word family. You could feel everyone try to make room for it.

I stepped forward. “I’m Cal,” I said. “We’re a volunteer group. We stood in so she wouldn’t leave without a name. If you’ll stand with us for seven minutes, we’ll put everything back in your hands.”

Ava’s eyes slid to the casket, then to the folded flag waiting on a table like a question that needed a person. She nodded once. Lucas squeezed her shoulder, the kind of squeeze men use when the words they want would sound like begging.

They sat in the front row. The air shifted, a knot loosening because something true had arrived.

I glanced at Jonah; he gave me a small nod and tucked his photograph close. The nurse folded her hands. We restarted the service, not from the beginning but from the place where people can step in without missing the point.

I read Maya’s name again. “Lieutenant. Medic. Healer.” The bugler tested a quiet note he didn’t yet play. We kept our silhouettes small so the living could have space.

When the last word settled, I asked the room for patience. “We’re going to step into the family room for a moment,” I said. “We’ll be right back.”

The family room had a window that looked out at a narrow alley and a tree that hadn’t decided whether to keep its leaves. Someone had set out a tray with water and a plate of store-bought cookies that tried hard to taste like a bakery but didn’t.

Ava sat at the edge of the chair, back straight, hands clasped so tight her knuckles blanched. Up close, she looked older than she had from the aisle and younger, too; grief does that math wrong on purpose.

“She was our mother,” Ava said without preface. “And she wasn’t. She was on the phone during dinners. She left early from birthdays to ‘go check on someone’ and didn’t say who. She forgot my first college visit. She said she’d make it up to me. She didn’t.”

Lucas didn’t flinch. He kept his eyes on the window as if the tree might offer a verdict. “I’m her brother,” he said softly. “I saw the hero part. I also drove a teenager to urgent care once because a panic attack felt like dying and her mom was on the line with someone who might literally die. Both things are true.”

I let the words stand. You don’t argue with a person’s lived hour-by-hour. “We didn’t know how to find you,” I said after a moment. “The paperwork didn’t have next of kin. We found a name, a service record, and the word tomorrow.”

Ava wiped under one eye with the side of her thumb in one fast, practical motion. “We weren’t notified,” she said. “But not being notified doesn’t mean we weren’t here. It means we were still trying to be mad long enough to win an argument with a person who keeps not showing up.”

There it was—anger doing laps around love because it didn’t know where else to go.

Before I could answer, a knock sounded soft against the frame. The nurse stepped in. “I don’t want to intrude,” she said. “But if this is the right time, I’d like to show you something.” She held a thin folder, the kind you use because it’s what’s there, not because it matches anything.

Inside: a photocopy of a handwritten letter. The paper had the faint shadow of an old hospital logo in the corner, the ink lifted just enough by the copier to look like it might run if you breathed on it. The nurse placed it on the table and set her palm on the edge to stop it from floating away.

“Fifteen years ago, a soldier died on our ward,” she said. “I don’t need to tell you his name. We called his family. Lieutenant Torres wrote a letter to them after the official notice. She did that sometimes. This is a copy the family gave me the year after, when they brought cookies on his birthday and wouldn’t let us return the Tupperware.”

Ava hesitated, then pulled the page closer. Lucas didn’t move but the tendons in his neck did.

I watched her mouth form the words before her voice found them. “He wasn’t alone,” she read, barely above a whisper. “He asked me to tell you he was thinking of the summer at the lake and the blue cooler that never latched. He laughed about it. He said he could hear the stupid lid banging with every wave. He told me to tell you that’s the sound he’s taking with him—home.”

She stopped and pressed her lips together. The letter wasn’t long—two paragraphs and a sentence that said thank you for letting us care for him; I carried his name with me to the end of my shift and beyond. At the bottom, a signature: M. Torres. No flourish. Just the name as if it were equipment you trust.

The nurse lifted another sheet: a small receipt with the ink mostly gone and a note in the corner, anonymous grocery card for family — please deliver discreetly. “She didn’t have money,” the nurse said. “But when someone lost somebody, groceries would show up. Sometimes from a group of us. Sometimes I’m pretty sure from just her.”

Ava closed her eyes and exhaled like she’d been holding a breath for fifteen years. “She never told us,” she said. Not accusation, not wonder. Just information finally sitting where it belonged.

“We’re not here to make her perfect,” I said. “I don’t think she would want that. Perfect people aren’t any help in the dark. We’re here because when the dark showed up, she didn’t check a clock.”

Lucas nodded once. “She also didn’t check ours,” he said. The sentence landed and didn’t break anything; it just made more room for what was already there.

From the doorway came a careful voice. “I’m sorry,” the funeral director said. “A woman outside asked if she could speak for just a moment. She brought something for the family. I can ask her to wait.”

Ava folded the letter and unfolded it again as if the crease could tell her what to do. “Let her in,” she said.

The woman who stepped inside wore a denim jacket and a ring with a stone the color of creek water. Sixty-something, hair in a braid, the kind of face that gets mistaken for stern until it smiles. She didn’t smile now.

“My brother died in the same year this letter was written,” she said, voice like gravel made of kindness. “Not the same man, different unit. We got one, too. We kept it on the fridge for a month, then in a shoebox for years because we were afraid it would fade in the sun.” She held out an envelope with careful fingers. “I’m not sure if this is right, but it feels like it might be. It came with our letter, taped to the back. It says it was meant for ‘the family of a family.’ I think that’s you.”

Ava took the envelope. The paper had been opened and resealed and opened again. On the front, in the same block letters I’d seen on the index card from Maya’s pocket, someone had written: If this ever finds the people she loved first, tell them she never forgot the sound of their house. No names. Just sound. The return address had been scratched out with a ballpoint pen, then written again faintly and then scratched out a second time, like a person trying to decide whether to exist on paper.

Ava slid out a single folded page and a pressed wildflower, paper-thin from years under a book. The flower had lost its color but not its shape.

She read silently. Her chin trembled, then stilled. She handed the page to Lucas. He read faster, then slower, then carried his hand over his mouth as if to keep something from leaving.

“What does it say?” I asked gently, only if she wanted to share.

Ava didn’t hand it to me. She didn’t have to. “It says she was going to try to be two kinds of mother,” she said. “One who comes home on time and one who answers the phone when it rings at midnight. It says she knew she’d fail at both some days. It says she was still trying.”

On the back of the page, in smaller handwriting, a list of first names. I recognized the pattern: the same list style as the index card we’d found—first names, little notes. Beside one: Ava — ask about the lake cooler. Beside another: Lucas — bring extra sweater; he won’t ask.

Ava brushed the pressed flower with the tip of her finger, then set it gently on the table as if it were a landing bird. Her voice didn’t crack; it changed key.

“What else did she hide,” she whispered, not to accuse but to inventory. “What else did she keep safe where we didn’t think to look?”

Out in the chapel, through the thin wall, the murmur of voices swelled and then softened like the sound of a crowd deciding whether to stay. The bugler tested that quiet note again. Jonah’s cane tapped once in patient time.

I looked at the folded flag waiting on its table and then at Ava, who now had a piece of her mother that wasn’t just absence. “We’ll finish what we started,” I said. “With you.”

She nodded, a small motion, but decisive. Lucas let out a breath that made the glass rattle faintly in the frame.

We stood. The nurse held the door. The funeral director smoothed the edge of the tablecloth with palms that were no longer shaking.

When we stepped back into the chapel, the room stood with us like a single organism learning how to breathe again. The aisle opened. The light shifted. And for the first time since the phone rang at 1:07 p.m. the day before, I felt the next part of the story lean forward to meet us.

Part 4 — The Unlocked Wooden Box

We finished the seven minutes I’d promised.

Names spoken. A verse read. Silence held like a formation that knows when to breathe. The bugler didn’t play; this wasn’t that service yet. The folded flag stayed on the table, waiting for the right pair of hands.

Afterward, the funeral director touched my sleeve. “There’s something else,” she said. “It came in with her personal effects from the hospital. No one’s opened it beyond inventory.”

She led us down a short hall to a storage room that smelled like lemon cleaner and cedar. On a metal shelf sat a small wooden box, no lock, no latch—just two brass hinges and a lid rubbed smooth by years of handling. Someone had written TORRES, M. on a piece of masking tape and stuck it to the side at a tilt.

Ava didn’t move. Lucas did. He slid the box toward us and looked at his niece. “You want to—?”

She nodded once, then set both hands on the lid the way you steady yourself before you lift.

Inside: not much, and exactly enough. A spiral notebook bent at the spine. A folded field map with the creases worn nearly translucent. A cloth pouch holding a battered stethoscope head and a nametag with the corners rounded by time. An index card with the same block letters we’d seen before—IF IT’S MIDNIGHT AND YOU’RE ALONE, CALL ME. IF IT’S 3 A.M., CALL TWICE. And on the bottom, a small digital recorder with a sticky note on it in blue ink: Play when you’re ready.

No passwords. No locks. It looked like something meant to be found.

The nurse stood by the door and didn’t pretend not to care. “We kept it sealed,” she said. “We thought a family should hear whatever it is first.”

Ava picked up the notebook. First page: Night Watch. Below it, a list of dates and initials, some with small notes—ask about the dog, bring gum, don’t knock—text first. A few pages later, a hand-drawn chart with hours marked in blocks and a line that read: If you’re the only light on the floor, be the kind that doesn’t blind people.

She put the notebook down like it was warm.

Lucas turned the field map over and smiled in a way that hurt. “She drew herself home routes,” he said, tracing little arrows along streets we recognized. “Shortest way from the hospital to our old place. And backup routes for when the bridge is closed. Habit.”

I picked up the recorder. It was the kind people use when they don’t trust their memory to keep quiet. The sticky note flapped once and settled. “Ava,” I said, holding it out. “You or me?”

She stared at the little screen, then nodded. “You,” she said. “I’m afraid I’ll drop it.”

I pressed play. The sound that came out wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. A room can get quiet when a voice asks it to.

“Hey,” Maya said, a little breathless, like she’d recorded in a hallway between calls. “If you’re hearing this, it means one of two things. I’m running late again, or I ran out of time for good. If it’s the first one, stop rolling your eyes. If it’s the second—okay.”

The recorder clicked as if she’d shifted it from one hand to the other.

“Ava,” she said, and the name was a held thing. “And Lucas, if you’re there. And anyone else who came instead because that’s what you do. Listen up.”

A tiny rustle; paper sliding; a life you could hear.

“I tried to be two kinds of person,” she said. “The kind who comes home on time with ice cream for no reason, and the kind who picks up the phone at midnight when someone says they can’t feel their hands. I didn’t do either well every day. I know that. I am sorry for the times I made you carry my absence like it was your job.”

Another rustle. A measured breath.

“If I go before you get the chance to forgive me in person,” Maya continued, “do me a favor. Give the flag to whoever needs it to stand up straight. If that’s you, Ava, take it. If you’re not ready, hand it to someone who’s practicing standing until you are. And bring me back to my unit.”

She let the words sit. They didn’t echo. They didn’t need to.

“By unit,” she said, and I could hear a smile I recognized from a hundred hallways where people keep each other alive, “I mean the people who show up. The ones who sit with the kid at 3 a.m. so he’ll see sunrise. The ones who argue with vending machines on other people’s behalf. The ones who don’t need a patch on a sleeve to do the job. Wherever they gather, that’s home. If there’s room near those who served, lay me there. If there isn’t, a quiet spot is fine. Just make sure no one is alone if you can help it.”

The recorder caught a distant overhead announcement. She waited it out like a person used to waiting out overhead announcements.

“Ava,” she said again, softer. “Ask about the lake cooler for me. Make sure Lucas brings a sweater. Tell him I know he won’t, but ask anyway. And if anyone is playing this who isn’t blood but is family, do what you always do: keep watch.”

A click. Silence. The cheap speaker whirred for a second and then stopped.

No one talked first. The room did its math again—age, love, duty, resentment—numbers that never add up clean, just close enough to carry forward.

Ava wiped her face with both hands like she was washing it without water. “She knew,” she said. Not a question.

“She knew,” Lucas echoed.

The nurse let out a breath she’d been keeping since we’d opened the lid. “She used to clip her badge upside down on night shift,” she said, almost smiling. “Said the clatter woke people. Walked in socks until the person in the chair fell asleep. Kept a spare toothbrush in her pocket for kids who forgot to go home first.”

I held up the notebook. “There’s a line here,” I said. “If you can’t fix it, witness it.”

The nurse nodded. “She lived like that.”

“Let’s make copies of the pages with numbers,” I said. “Not to pass around—just to know who might need a call today.”

Ava looked at the recorder as if it might speak again if she dared it to. Then she slipped it into the pocket of her jacket. “I’ll hold onto this,” she said. “For a while.”

“Take the box,” the funeral director said. “It’s yours.”

Back in the chapel, news moved the way it moves when it’s not trying to be news: phone to phone, palms to pockets, people to people. We didn’t post anything. We didn’t have to. Someone who’d come to drop off flowers texted a neighborhood chat: Unclaimed medic. Community standing vigil. Bring a chair, bring your heart. A local paper called the funeral home asking for confirmation. A teacher down the street put a handwritten note in her window: Not Alone Today.

My phone started to light: gray bubbles stacking on gray bubbles.

Cal, we can form a color guard if needed.

Two of us from three counties over. ETA 1900.

I’ve got a van and coffee. Who needs rides?

I’m a counselor—can sit with folks if it gets heavy.

My dad says Maya patched him up in ’08. He’s in a wheelchair now. We’re coming.

The parking lot changed pitch. You can tell, even indoors, when a space outside fills with people who decided together. The air hums. The light at the edge of the doorframe shifts.

I stepped to the entry and looked out. A line of cars stretched past the corner, turn signals ticking like metronomes. Two retirees in dress coats unfolded a travel flag and weighed the base with a bag of sand. A kid stood on a curb, holding a handmade sign that said THANK YOU, LT. TORRES in marker that bled a little at the edges.

The funeral director came to stand beside me. “We’ll need more chairs,” she said.

“We’ll need more everything,” I said. “We’ll take the street if we have to.”

She nodded like a person who knows about permits and neighbors and how communities decide to bend rules without breaking them. “We can ask the businesses next door if we can use their lots after hours,” she said. “I’ll make calls.”

“Cal?” the nurse said from behind me. “If the room gets too full, find a smaller room for folks who don’t like crowds.”

“On it.”

We moved like people who’ve done this before in other contexts, different reasons, same muscles. Water jugs. Trash bags. A sheet of poster board taped to a wall: Need / Have. Under Need, someone wrote cups. Under Have, someone wrote tissues. Someone else added one bugle, slightly dented with a smiley face.

Ava and Lucas sat together in the front row again, the wooden box at their feet. Every so often Ava rested her palm on the lid as if to remind it they were still here. People approached in ones and twos, offering a hand to squeeze, a name to speak, a story to lend. No speeches. Just little human stitches.

By late afternoon, the sky turned the color of a pressed flower. My phone buzzed again—unknown number, out-of-state. I stepped into the hall to answer.

“Rivera?” a voice said, careful and breathless at once. “I heard about Maya Torres. I think I’ve been looking for her for sixteen years.”

I leaned against the cool wall and closed my eyes for one beat, feeling the shape of the next hours pressed against us from the other side.

“How far out are you?” I asked.

“Three states,” he said. “We’re driving through the night.”

I looked back at the chapel where a flag waited and a box breathed cedar into a room that had learned how to hold things it hadn’t planned for.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll keep the light on.”