Part 7 — The Will That Ran Out of Time

“Let’s fix what her paperwork can’t,” Ava said, and the room obeyed like it had been waiting for orders.

We split the work into things hands could hold. The funeral director called the cemetery office with the kind of voice that gets doors open—polite, specific, unafraid to repeat a question. Reed stepped into the hallway and phoned a community foundation about acting as a fiscal sponsor until a boring, permanent structure could exist for Last Watch. “No plaques,” he said into the receiver. “Just receipts and a way to help at 3 a.m.”

The nurse drafted a rough board on a legal pad: nurse, counselor, two veterans, one family member, one community seat. Under it she wrote rules like bandages: no storytelling required to receive help, publish the numbers, privacy first, no photos at distribution, re-check the helpers.

Lucas handled logistics like he’d been born to carry clipboards; he wasn’t—he just understood that grief breaks if you don’t give it something useful to do. He made a list under the program with FLAG STAYS:

- confirm eligibility with service record

- check local rules for scattering at sea

- travel for immediate family

- contact the honor guard list the director mentioned

“That’s the easy part,” the director said, setting the phone against her shoulder while she typed. “The service record office will need time, but we can begin the cemetery process with preliminary verification. Not promises—just progress.”

“Progress is a promise’s little cousin,” Jonah said from the second row, and a grin flickered like a pilot light.

I took the manila envelope with the handwritten will and put it in a clear sleeve, then photographed each page on my phone. “This isn’t legal advice,” I said, “just common sense. We’ll speak with a clinic that knows the steps. Meanwhile, we honor what she asked because the people with standing are in this room.”

Ava rubbed her thumb across the brass corner of her mother’s name tag. “We’re not fighting paper,” she said. “We’re following it as far as it will walk and carrying it the rest of the way.”

The chapel door opened a careful handspan. A young man stood there in a thrift-store suit jacket two sizes too big, hair cropped short, determination holding him up where sleep would have done better. He didn’t come down the aisle at first; he checked the room’s temperature like a person who has learned to listen before entering.

“Come in,” I said.

He stepped forward, palms empty, eyes bright with the kind of gratitude that makes you want to look at your shoes. “My name is Eli,” he said. “I don’t want to take time. I… was in a bad place a few years back. Someone gave me an email address and said try it even if it felt stupid. I wrote at 3:11 a.m. I expected silence.”

He slid a creased printout from his inside pocket, edges velvety from handling. At the top was a timestamp—03:14—three minutes later. He held it with the reverence people usually save for photographs.

“I printed this the day after and kept it,” he said. “I covered the address with tape. I’m not here to tell my story. I just… this saved me.”

He offered the page toward Ava, but she kept her hands at her sides, then nodded at me. I took it like you take a newborn: steady, careful, with the knowledge that your hands will be remembered by whatever happens next. The reply was a handful of short lines:

Breathe with me: four in, four hold, four out. Again.

You are not failing. Your body is loud because it wants to live.

Name five things you can see. Four you can touch. Three you can hear. Two you can smell. One you can taste.

Set a timer for ten minutes. Text me when it dings. I’m here until sunrise.

No diagnoses. No sermons. Just someone offering steadiness across wire and darkness until a clock could take over.

Eli pointed to the bottom line. “She wrote, ‘Eat something simple. Drinking water counts.’ Then she sent a picture of a granola bar and said, ‘Pretend it’s gourmet.’ I still carry one for other people.” He patted his pocket—crinkle of wrapper, present tense charity. “I wanted you to know your mother sat with me until the timer had gone off six times. Then she wrote, ‘Sleep. I’ll be here when you wake up.’ When I woke up, there was a message that said, ‘Good morning, soldier. Go stand in the shower and let the water prove the world still moves.’”

The nurse pressed her lips together in a way that kept her from crying and from interrupting. We all did our own versions of that.

Ava reached for the paper then, finally. She read the lines like she was memorizing someone else’s heartbeat. Her mouth quirked. “She ate those same granola bars,” she said. “Then yelled at them for being dry.” That got a soft laugh that didn’t push anyone off their chair.

“Thank you,” she told Eli. “You didn’t have to bring this. I wouldn’t have asked. But thank you.”

He nodded once, the kind of nod that seals an oath you didn’t sign in ink. “If the fund happens,” he said, gesturing toward the legal pad on the table, “I can help with night shifts on the chat. I’m good in the dark now.”

“Add him,” Lucas said, pen already moving.

Outside, the day tilted. The street carried more feet. A barbershop customer wandered out with half a haircut, a cape around his shoulders like a flag, to ask if we needed more water. Two high schoolers in choir polos arrived with a portable speaker to lend and a willingness to lift. They stood awkwardly until the nurse handed them two cases of cups and permission to be useful. The world kept showing up in the shape of exactly who lived nearby.

The funeral director’s phone buzzed. She listened, thanked the caller three times, and hung up. “Preliminary verification is good,” she said. “We’ll need the official documents, but the cemetery can pencil a date pending the paperwork. We’ll aim for next week, weather permitting. The honor detail can likely make it.”

No one cheered. Relief doesn’t always look like noise. Ava sat down as if someone had taken a weight from her shoulders she didn’t realize she’d set there.

“Scattering?” Lucas asked. “She asked for sky.”

“We’ll check the rules,” the director said. “We’ll do it right.”

Reed stepped back into the room, gave a short thumbs-up. “Fiscal sponsor is willing,” he said. “They’ll host Last Watch temporarily so contributions are tax-deductible and traceable. We set it up as a separate account. You”—he looked to Ava—“and whomever you name approve disbursements. I won’t touch a penny without two signatures.”

“We’re not announcing an amount,” Ava said, wary.

“We aren’t announcing anything,” Reed replied. “We’re making a tool. If someone asks how to help, we say ‘Here,’ and hand them a wrench.”

Before we could settle the next three practicalities, the funeral director appeared again with that careful face—compassion edged by responsibility. “Local news is outside,” she said. “They’ve kept their cameras down and asked permission to come in. They say they can shoot from the doorway, faces turned away, no casket on screen. They heard about a community service for an unclaimed medic and want a thirty-second quote for the evening broadcast.”

The word news tightened the room in the small ways: shoulders raised a notch, chins tucked, eyes narrowed like a lens had been introduced. We aren’t allergic to attention. We are wary of it.

Ava looked at the flag, the cedar box, the index card. “Boundaries,” she said.

“We set them,” I answered. “No close-ups. No minors. No casket. No fundraising pitches. No one has to speak.”

The nurse added, “They can film the sidewalk sign and the Need / Have board. That’s what this is. Need and Have meeting halfway.”

Jonah adjusted his tie. “If they want a quote,” he said, “give them one sentence that isn’t about tragedy. Give them a sentence about effort.”

Ava stood. “I’ll do it,” she said. “This is ours.”

We met the reporter at the doorway. She kept her word. The camera stayed low, focused on hands stacking chairs, on the taped Quiet helps sign, on a pair of veterans lifting a cooler like it was a meaningful object because, right now, it was.

“Thirty seconds,” the reporter said. “We can cut if you want to redo. Or we can skip it.”

Ava didn’t rehearse. She didn’t need to. “My mother served as a medic,” she said to the microphone without looking at it. “She helped strangers at 3 a.m. and forgot to help herself. We’re doing two things in her name: the burial she earned, and a small, boring fund that keeps people company on hard nights. If you want to help, show up for someone inconveniently. That’s the only advertisement.”

That was it. The reporter nodded, thanked us, and backed away like leaving a chapel.

Back inside, the day settled into a purposeful rhythm. We learned how to say no kindly and yes carefully. We learned how to walk people to the quiet room before their breath shortened too much. We learned how many cups a street can drink (a lot), how many cookies a grief can eat (more than you think), and how a community becomes a machine when it’s well-oiled with small instructions.

Near dusk, the sky went copper. The bugler practiced a scale under his breath and stopped at the third note, tucking the horn against his ribs. The hallway clock nudged us forward.

My phone buzzed hard enough to jump on the table. A text from the cemetery office: Tentative slot confirmed—Thursday, 10 a.m., pending documents. Honor detail available. Another from a contact two counties over: Heads up—news spot is running at 6:00. People are on their way.

I stepped to the doorway. Past the last parked car, headlights crested the hill in a slow, careful line, turning into our block one by one. You can hear hope arrive if you’ve been in enough rooms where it was late—tires whispering, doors closing, feet finding pavement.

Ava came to stand beside me, the manila envelope under her arm, the recorder in her pocket, the worry and the relief sharing space behind her eyes.

“Is this going to get too big?” she asked.

“It’s going to get exactly as big as it needs to,” I said. “And we’re going to keep the edges humane.”

Down the block, a high school choir began humming while they waited for the camera to move on. The note carried. Someone took up harmony. A stranger handed another stranger a cup of water like communion.

The reporter’s van pulled away without lights. The line of headlights kept growing.

Inside, the flag waited, the cedar box breathed its small cedar breath, and Jonah’s cane tapped once, exactly in time with the first chords the choir found without asking.

The city, it seemed, had decided to stand watch with us.

Part 8 — The City Stands at Attention

The news spot lasted thirty seconds. The street stayed for hours.

By dusk the block had the hush of a church and the coordination of a firehouse. Chalk arrows on the sidewalk pointed to water, to restrooms, to the Quiet helps room the nurse guarded like a lifeboat. Brown paper bags with tea lights—some real, some battery—made a soft runway from the curb to the chapel. The Need / Have board had become a little marketplace of mercy:

Need: jackets, chairs, patience.

Have: blankets, coffee, two counselors, one horn that still refuses to play the high note.

No jar. No QR codes. No pitches. A handwritten index card taped beside the board said, No donations here. Give your time. Give your seat. Give someone a ride home.

The high school choir had grown by word of mouth into a half-moon of teenagers with straight spines and nervous hands; they hummed under their breath while they waited for someone to tell them where to put the sound. An older neighbor walked up and down the line laying a gentle palm on each shoulder as if tuning an instrument.

A patrol car rolled past slow and then parked a block away with the engine off, the officer standing beside it with arms folded and eyes wet, another citizen leaning on the evening.

We set the vigil at 7:00 because the light is kind at 7:00. I stood at the makeshift mic—just a borrowed speaker and a long cord—and didn’t introduce myself as anything. Titles get you attention. We wanted focus.

“Thank you for being here,” I said. “We’re going to keep this simple. A minute of silence. Then, if you have one sentence, a memory, a kindness she did that you can describe in thirty seconds, come say it and let the next person stand here. We aren’t telling the whole story. We’re making sure it can be carried.”

We began with quiet. Hundred-plus people breathing in the same key. Somewhere down the block a dog barked once and then never mind. When the minute ended, I stepped back without adding weight.

A hospital custodian spoke first, cap in hand. “Night shift,” he said. “She left a sticky note on the breakroom fridge that said, You can clock out and still keep watch. I thought about that a lot.”

A security guard followed. “She learned everybody’s name,” he said. “Even mine. She called me by my first, and I forgot I was invisible.”

A barista from the corner café, still wearing an apron with a constellation of coffee stains, took the mic and held it like a fragile thing. “She’d come in late,” she said, “and order ‘whatever is hot and honest.’ She’d pay and then slide a gift card across the counter and say, ‘If someone looks like they need to sit, don’t make them explain why.’”

A teenager with a cracked phone screen read from it, voice shaking. “She told me once, ‘If you can’t fix it, witness it.’ I wrote that in my notes app and left it there. Tonight I looked at it again.”

Not every story had her name in it. Some had only a shape you could recognize if you’d ever been steadied while your world spun. People kept themselves to thirty seconds as if brevity were a shared discipline.

The bugler stood near the chapel doors, horn tucked against his ribs. He didn’t lift it. Taps belongs to another day. Tonight needed a different instrument.

I turned to the choir and lifted a hand. They inhaled as one, found a single note they could hold without being dramatic, then let it spill into a simple harmony that climbed a little and came home. No lyrics. Just tone. The sound threaded the crowd and laced the evening together.

Ava stood beside the flag and the cedar box, both hands in her jacket pockets the way people stand when they need to be braced without showing it. When she stepped forward, the crowd didn’t clap. It made space.

“I used to hate the sound of a cooler lid that wouldn’t latch,” she said. “We had one at the lake—the lid banged with every step from the car to the dock. My mother wrote about that sound to a family when their son died. She told them he remembered it. I didn’t know that until this week.”

She looked down at the triangle of stars. “I found the old cooler in our garage last night. The lid still doesn’t cooperate.” She smiled, small and unplanned. “I think… I think I’ll keep it that way.”

From somewhere in the crowd, someone tapped twice gently on the lid of a plastic storage bin we’d been using to hold cups. The sound was small and familiar. A second tap came from farther back. Then a third. It didn’t become a performance. It stayed a private joke the entire street shared for two seconds and let go.

“I’m not ready to be the person who can carry this flag home today,” Ava said. “But I’m ready to hold it while we stand here together.” She lifted the triangle, and the crowd shifted like a flock when one bird changes height. She stood with it against her chest while the choir added a lower note to their chord.

She didn’t hold it long. She set it back on the table facing outward—stars offered, not displayed—and stepped aside.

We kept the mic moving. A mail carrier. A night nurse from a different floor who said Maya kept a stash of warm socks in a drawer and wrote “Take two” on the box. A taxi driver who once drove her to three addresses in an hour, no tips, and said she never apologized for making him loop back to a door to check if the porch light had turned on.

People inched forward with cups of water and moved back with their hands empty and their faces reassembled.

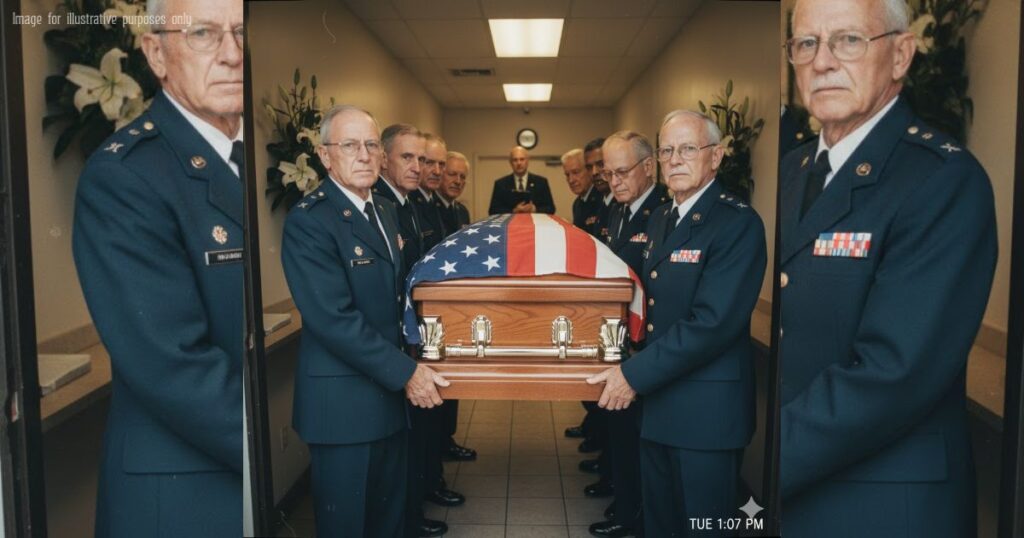

Near the corner, a small group in dress uniforms waited, hats under arms. Not the formal honor detail—that would come later at the cemetery—but a group of veterans who knew the drill and had decided to stand in as a promise. At 7:30, one of them gave a short set of commands you could hear without it feeling like a show. They presented arms to the flag on the stand by the chapel door—starch and steel held for eight long counts—and lowered them together. The gesture didn’t wrap anything up. It pinned it to the day.

Reed stayed near the edge, speaking quietly with people who asked how Last Watch would work. He didn’t pass a sign-up sheet. He passed phone numbers on paper torn from a legal pad: If you can sit up till 2 a.m. twice a month, text this number. The nurse added, If the night gets loud in your head, text the same number. You don’t owe us your story.

Somewhere behind me a child asked, too loud, “Are we done?” and a parent whispered, “Almost,” and I decided that was the right time.

“Two minutes,” I told the crowd. “Then we’ll let the night go back to being night.”

The choir found a final chord and held it like a bridge. I stepped to the mic.

“Thursday, ten a.m., we’ll stand at a place with more sky,” I said. “Between now and then, some of you will want to help. Here’s a short list: bring someone soup without posting it online. Ask a neighbor if they need anything at midnight. Put your name on the Last Watch sheet if you can sit quietly without needing to be a hero. And if you need help—tonight, tomorrow, next week—write a time on your palm and show it to one of us. We’ll read it and we’ll understand.”

I could have left it there. The city seemed ready to exhale. But rooms like this always save one more truth for last.

From the far edge of the gathering, a woman stepped forward, apologizing with her hands before her mouth could form the words. Denim jacket. A ring with a stone the color of creek water. She moved through the crowd the way someone moves down a pew—soft steps, shoulders turned, purse clutched like a passport.

“I’m sorry,” she said when she reached us, and the crowd responded in that strange, kind way crowds can: no one spoke, but space appeared.

She stood before the table with the map and the nametag and the index card, set her purse down, and pulled out an object wrapped in a grocery bag. She peeled the plastic back and there it was: a blue cooler lid, old plastic gone chalky at the edges, the latch stubborn as a memory.

“I’ve carried this in my trunk for fifteen summers,” she said, voice steady, eyes not. “My husband kept the rest of the cooler. He said he couldn’t fix the lid because the sound was his brother. When he died, I kept the lid because the sound was him.” She looked at Ava. “I think it might be yours now. Or maybe it belongs here for a while.”

She reached back into her purse and lifted a second thing: an envelope, the paper gone the color of tea, the flap taped and then untaped and taped again. She held it so we could see the corner: a hospital logo, faint as breath. “This is the letter,” she said softly. “The one she wrote us. We made a copy years ago and gave it to the ward. We kept the original. I brought it because—” She stopped, swallowed. “Because there’s one more page. I never sent it to the hospital. She came to our door the day after the letter arrived. She left something else.”

The crowd tightened the circle without closing it. I felt the room go to that place where it takes off its shoes and waits.

The woman laid the cooler lid on the table like a relic, the old latch clicking once and then settling. She tapped the envelope with a fingertip. “It’s time it goes home,” she said. “But before I hand it to you, there’s a part your mother never put in writing. It’s about why she left our house late that night and who she went to see before dawn.”

She looked at Ava’s face and then at mine, the way people look at the person who can catch things that fall.

“I think it will change what you do next,” she said.

And the last light of the day leaned across the table, caught the triangle of stars, and waited with the rest of us to hear what had been kept back for this exact moment.