Part 1 – The Text on the Cold Bench

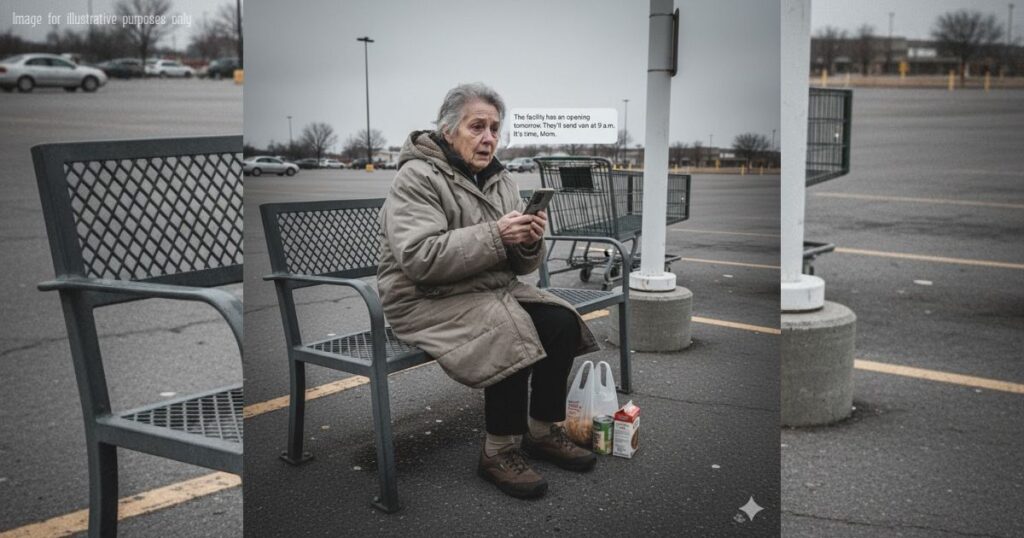

The veterans found me shivering between the shopping carts and the faded flagpole outside a discount supermarket, two grocery bags at my feet and the text message where my only son quietly erased me.

That was the moment my life got rewritten by strangers.

I had been on that metal bench so long the cold had crawled from the steel into my bones. My fingers, once steady enough to sew arteries together, now shook around a wrinkled grocery receipt and a plastic bag of generic cereal. Cars slid in and out of the lot, headlights sweeping past like nobody wanted to look too closely at an old woman who’d been left behind.

My son Daniel had said, “You go get what you need, Mom. I’ll circle the lot and pick you up by the entrance.” It sounded kind, almost. Matter-of-fact, like we’d done this a hundred times. I believed him because I wanted to.

Inside, I’d walked the aisles counting prices, subtracting each item against my pension in my head. Pasta, canned soup, milk, the cheapest coffee they had on sale. My knees ached, my hip flared, but I told myself I was “still independent,” the way people do when they’re afraid the word might not fit anymore.

When I came out, Daniel’s car wasn’t there.

I waited, because that’s what mothers do. We wait through soccer practices and missed curfews and silent treatments. We wait because somewhere deep inside we’re still holding a baby who once reached for us with chubby hands and absolute trust.

Ten minutes passed. Then twenty. The sun dropped behind the strip mall and the temperature with it. I dug in my coat pocket for my phone, telling myself there had been traffic, an emergency, anything but what the hollow space in my chest already knew.

His message was waiting for me.

The facility has an opening tomorrow. Memory care, good reviews. They’ll send a van to get you at 9 a.m. It’s time, Mom.

No “I’m sorry.” No “Can we talk about this?”

Just “It’s time,” like I was an appointment to be checked off a list.

I stared at the words until they blurred. My thumb hovered over the screen, but I didn’t know what to type back. What do you say to your own child when he’s just informed you you’re a problem he’s outsourcing?

I was still frozen there when I heard the sound of boots and low voices, and then laughter that didn’t belong to anyone in the parking lot.

They came into view all at once, a knot of men and women stepping out of a low brick building next to the supermarket. The sign above the door said “Veterans Resource Center” in peeling blue letters. Some wore jackets with unit patches, some had worn ball caps pulled low, all of them carried the solid heaviness of people who had seen things they don’t talk about at dinner.

One of them, tall with shoulders like a doorway and a close-cropped gray haircut, stopped midstep. His eyes found me the way a medic’s eyes find someone on a battlefield, scanning for what’s wrong before they even know your name.

He nudged the man next to him. “She’s still out here,” he said quietly. “That’s the third time we’ve passed.”

I dropped my gaze to my shoes. If you don’t meet people’s eyes, sometimes they decide you’re invisible and move on. I didn’t want pity. I didn’t want questions. I wanted my son to come back and tell me it was all a misunderstanding.

“Ma’am?” a voice said. “You okay out here?”

I looked up into the gray-haired man’s face. There were deep lines around his mouth, a pale scar near his temple, and a softness in his eyes that didn’t fit the rest of him.

“I’m fine,” I said, because that’s what we say when it’s clearly a lie. “Just waiting for my ride.”

“In this cold?” he asked. “How long you been waiting?”

I checked my watch and realized the hands meant nothing; time had turned to fog. “A little while,” I muttered. “He’s just… delayed.”

A younger woman in the group glanced at my plastic bags and the tremor in my hands. “Do you need us to call someone for you?” she asked. “Family? Friend?”

The word “friend” hit harder than it should have. I had colleagues once, neighbors, people who invited me to barbecues and book clubs. Somehow, in the slow erosion of years, they’d faded away, and I hadn’t noticed until my phone history was nothing but pharmacy reminders and spam calls.

“My son will come,” I said, too quickly. “He’s busy. He’s got work, kids, a lot on his mind.”

“He texted you?” the gray-haired man asked gently. “Can I… is it okay if I see? Just to make sure you’re safe out here.”

Part of me bristled. I had been a surgeon, a major in the Army Medical Corps, a woman who told generals to step out of her OR. I wasn’t used to being spoken to like a fragile package.

But my fingers unclenched anyway. I held the phone out.

He read the message once, then twice, jaw tightening. The others leaned in, their voices dropping to that low register people use when they’ve just seen something indecent.

“Memory care,” one of them murmured. “Without telling her first?”

“Van at nine,” another said. “Like a furniture delivery.”

The gray-haired man lifted his head. “My name’s Marcus Hall,” he said. “Most folks call me Hawk. This place here is Liberty House. We’re a bunch of veterans trying to keep each other standing. You remind me of my CO’s mom. She’d have skinned him alive if he pulled something like this.”

I almost laughed, because if I didn’t it was going to turn into a sound I couldn’t control. “I’m Dr. Evelyn Ross,” I said. “Evelyn is fine. And I’m sure Daniel has his reasons. I can be… difficult.”

“Being old and honest isn’t difficult,” the younger woman said. “It’s called being alive.”

Hawk crouched a little so we were eye level. “Dr. Ross, it’s dropping under freezing tonight,” he said. “You shouldn’t be out here alone. We’ve got coffee, heat, chairs that don’t freeze you from the knees up. Let us at least get you inside while you figure out what you want to do.”

“I don’t want to be anyone’s charity case,” I snapped, the anger surprising both of us. “I’ve taken care of myself a long time.”

“I’m not offering charity,” he replied calmly. “I’m offering respect. There’s a difference. You decide what happens next. We just don’t walk past people who look like they’ve been left behind.”

The words “left behind” landed like a diagnosis.

I thought of the van Daniel had scheduled, the strangers who would show up tomorrow morning, call my name off a clipboard, and drive me to a locked wing that smelled like bleach and overcooked vegetables. I imagined my name on a whiteboard outside a room, next to numbers rating my fall risk and memory score.

“I don’t want to go,” I whispered before I could stop myself.

“Then don’t make decisions sitting on a frozen bench,” Hawk said. “Come inside. Warm up. You can hate us in a heated room if you like. It’s better for circulation.”

That line, absurd as it was, carved a crack in the ice around my ribs. I stood slowly, knees protesting, and he took my elbow like I was something breakable, but not broken. The others scooped up my grocery bags as if they weighed nothing.

Liberty House was only a short walk away, but it felt like crossing a border. Inside, the air smelled of coffee, old wood, and something cooking in a crockpot. There were photos on the walls of people in uniforms, people out of uniforms, hands clasped on each other’s shoulders. A bulletin board sagged under job postings, support group flyers, handwritten notes that said things like “Call me if you feel the urge to disappear.”

As we stepped into the main room, a man sitting at one of the tables looked up from a battered deck of cards. He was in his thirties, maybe, with a beard he hadn’t quite committed to and a faded hoodie that said “MEDIC” across the chest.

His eyes widened. He pushed his chair back so fast it scraped.

“Holy—” he caught himself and swallowed the curse. “Are you… are you Dr. Ross? From the field hospital outside Kandahar? You used to braid your hair so it wouldn’t touch the sterile gowns.”

The room went quiet. All the air I thought age had stolen from me rushed back into my lungs at once.

“Yes,” I said slowly. “I was there. A long time ago.”

The medic stood, his voice unsteady. “You don’t remember me,” he said. “But you pulled shrapnel out of my chest when I was twenty-one. Everyone else said I wasn’t gonna make it. You yelled at them until they gave you another unit of blood. You’re the reason I’m standing here.”

Hawk looked from him to me, then down at the glowing screen of my phone, where Daniel’s message still sat like a bruise.

He set the phone on the table, turned it so I could see my own reflection in the black glass, and said quietly, “You saved a lot of us when the world was coming apart, Dr. Ross. Seems to me it’s our turn now. And I promise you this much.”

“No one is going to lock you away anywhere you don’t choose, not while Liberty House is watching.”

Part 2 – The Memory Test and the Bench in His Heart

They pulled more chairs over like it was the most normal thing in the world to stop an old woman from being shipped off by text message and sit her down for coffee.

Someone pushed a steaming mug into my hands, the chipped ceramic warm against fingers that still remembered the weight of surgical instruments. My reflection wobbled in the dark surface, lined and unfamiliar, like my face had been left out in the weather too long.

The medic—Rey, he introduced himself—sat across from me, elbows on the table. He kept looking at me like he was trying to line up the twenty-one-year-old bleeding on a cot with the seventy-nine-year-old holding cheap grocery bags.

“You ran that field hospital like a general,” he said. “You threw a tray once, remember? Some officer tried to tell you which patient was more important.”

I didn’t remember the tray, specifically. I remembered long nights and hot canvas tents and men who came in with eyes too wide and hands too still. I remembered yelling because sometimes yelling was the only thing that cut through fear.

“I’m not sure that was my finest leadership moment,” I said.

He shook his head. “You were the first person who talked to us like our lives were worth fighting for after we’d already done our fighting. Nobody forgets that.”

The room hummed with quiet agreement. I felt something loosen in my chest, something that had been coiled tight for years. It was a strange thing, being seen by people who had known a version of you you’d almost forgotten.

Hawk sat down next to me, the chair creaking under his weight. “Dr. Ross,” he said, “that message your son sent—do you want to tell us the rest of the story, or would you rather just warm up and not talk about him at all?”

The instinct to protect my child rose up before I could stop it. “He’s not a monster,” I said. “He has a stressful job, two kids, a mortgage that scares me just hearing the number. His wife’s been taking care of her own mother for years. They’re tired. I’m… extra.”

Hawk tilted his head. “Being tired doesn’t excuse leaving you in thirty-degree weather with no ride,” he said gently. “Stress can explain behavior. It doesn’t always justify it.”

I stared down at my hands. The tremor had calmed a little, but I could still see the faint vibration in my fingertips. “I forget things,” I admitted. “Sometimes I put the kettle on and then I sit down and read and the next thing I know the smoke alarm is shrieking. Last month I called my granddaughter by my sister’s name. It scared him.”

“Did it scare you?” the younger woman asked.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “But I would have liked to be asked, not handled.”

Rey tapped the table with one finger. “So instead of saying, ‘Mom, I’m worried, let’s make a plan,’ he scheduled strangers to show up tomorrow and drive you away?”

“That’s one way to put it,” I said. “He told me over breakfast we’d go pick up a few things at the store. I thought it meant milk and bread, not the end of my say in my own life.”

The words came out sharper than I expected. It felt like lancing a wound, messy but necessary.

Hawk reached toward the center of the table where my phone lay, screen still glowing faintly. “May I?” he asked.

I hesitated, then nodded.

He picked it up and studied the message again, thumb hovering near the screen but not pressing anything. “Do you want to call him?” he said. “From here, with us around if you need backup. Or would you rather rest first and deal with it later?”

“I should call,” I said. “If I don’t, he’ll say I was being unreasonable. He likes that word these days.”

“We’ll give you space,” Hawk said. “But we’re not going anywhere.”

He stood and gestured to a quieter corner of the room. I walked there slowly, my joints protesting. When I pressed Daniel’s name, my heart did the odd skip it does before a difficult surgery.

He picked up on the second ring. “Mom,” he said, breathless. “Where are you? The facility called. You weren’t home. I drove around the lot. You were gone.”

“I was not gone,” I said. “I was exactly where you left me. On the bench outside the store.”

There was a long silence. I could picture him running a hand through his hair, the way he does when reality doesn’t match the story he’d told himself.

“Mia said you got in a van with strangers,” he finally said. “She saw from the backseat. You scared her.”

“They’re not strangers,” I said. “They’re veterans. Some of them remember me from the field hospital. They brought me inside because it’s freezing, Daniel.”

“Mom, you can’t just go off with people you don’t know,” he snapped. “You wander, you forget things, you—”

“I walked thirty feet from a bench to a building,” I cut in. “I didn’t hitchhike to another state.”

He exhaled hard. “This is exactly what I was afraid of,” he said. “You making impulsive decisions. You don’t see that you’re slipping.”

My hand tightened on the phone. “What I see,” I said, “is that you arranged for me to be taken to a memory care facility without talking to me first. You drove away while I was buying groceries. You told me I was being ‘dramatic’ when I asked if we could at least visit the place together.”

“I didn’t ‘drive away,’” he said, his voice rising. “I went to sign paperwork. I told you that.”

“You told the back of my head while I was counting coupons,” I replied. “You didn’t look at me, Daniel.”

The silence on the line this time was heavier.

“Look,” he said finally, his tone shifting into the reasonable cadence he uses in work meetings. “I talked to an attorney. They said with your forgetfulness and the stove thing and the fall you had last year, there might be grounds for temporary guardianship. Not to take over your life, just to protect you. I can’t wait for you to set the kitchen on fire or wander off somewhere.”

A flicker of memory. The fall. The shame of lying on the kitchen floor, dizzy, trying to decide whether calling 911 was overreacting. I hadn’t told him about waking up on my own and crawling to the phone, fingers refusing to dial.

“Guardianship,” I repeated. The word tasted metallic. “So I’m a ward now? Is that the story you want to tell your children? Their grandmother is legally no different than a child?”

“For now, I just scheduled an evaluation,” he said. “Tomorrow. Neuropsychologist, memory testing, all of it. If everything’s fine, then great, I’ll apologize and we’ll figure out another plan. But if it’s not, we need to know. We need to act.”

The room around me blurred a little. On the far side, I could see Hawk and Rey pretending not to watch, giving me the illusion of privacy while staying close enough if I needed someone to lean on.

“I am not refusing an evaluation,” I said slowly. “I’m not afraid of information. I practiced medicine for forty years. But I am afraid of you using one bad test on one bad day to lock me away somewhere I never chose.”

“That’s not fair,” he said.

“Neither is a text message in a parking lot,” I replied.

He made a helpless sound, something between a sigh and a groan. “I’m trying,” he said. “You don’t see how hard this is.”

“You’re right,” I said quietly. “I don’t. I only see my side. Maybe that’s the problem.”

“Please just show up tomorrow,” he said. “We’ll go from there. I have to get back to a meeting.”

“Of course,” I said. “Your meetings are important.”

He either didn’t hear the edge in my voice or chose to ignore it. “I’ll send you the address,” he said. “And Mom… don’t trust those people too much, okay? You don’t know them.”

The line clicked dead before I could answer.

I lowered the phone and let my arm hang at my side. For a moment the floor seemed farther from my feet than it had any right to be.

Hawk appeared at my elbow. “How’d that go?” he asked softly.

“He’s scheduled a test to find out if my brain has betrayed me,” I said. “And if it has, he’ll have paperwork ready.”

Hawk’s jaw flexed. “You’re not a defective appliance,” he muttered. “You’re a person.”

“I forget names,” I said. “Sometimes I walk into a room and can’t remember why. Last week I put my keys in the freezer and spent an hour looking for them. Maybe I am slipping. Maybe he’s right to be afraid.”

He met my eyes. “We all slip,” he said. “You know how many of us have to write down what day it is three times before it sticks? Trauma does that. Age does that. One test doesn’t decide who you are.”

“I’ve seen what happens when the tests go badly,” I replied. “Families whispering in hallways. Doctors saying ‘capacity’ and ‘safety’ in the same sentence like they mean the same thing. Doors that lock from the outside.”

Rey came over, holding what looked like a folded blanket. “We’ve got a spare room down the hall,” he said. “Nothing fancy. Bed’s a little lumpy. But it’s warm, and no one will come in with a clipboard at nine a.m. unless you invite them.”

“I should go home,” I said automatically. “Sleep in my own bed. Be where he expects me to be.”

“Will someone be there with you?” Hawk asked.

I thought of the quiet apartment, the ticking clock, the way every sound at night had started to sound like a threat since my husband died. I thought of the van scheduled for the morning, of strangers at my door with forms for me to sign while I was still in my robe.

“No,” I said.

“Then stay here tonight,” Hawk said. “We’ll drive you to that evaluation tomorrow if you decide to go. You don’t have to walk into any of this alone.”

The word “alone” snagged something raw inside me. I looked at the hallway, lit by a row of mismatched lamps. Someone had taped a child’s drawing to the wall, crayon fireworks exploding over stick figures holding hands.

“Just for tonight,” I said. “I don’t want to get comfortable.”

“None of us are comfortable,” Rey said with a half-smile. “That’s kind of the point.”

They led me to a small room with a narrow bed, a dresser, and a window that looked out over the supermarket’s back lot. Someone had put a quilt on the bed, the kind made from old T-shirts and scraps of fabric, stitched together until they became something new.

I sat on the mattress and felt the springs protest. My bones did the same.

From the hallway, I heard Hawk’s voice, low and steady, talking to someone about rides and schedules and making sure I wasn’t left waiting anywhere alone again. They were making a plan around me, not for me, and the difference felt like air returning to lungs I hadn’t realized were half-empty.

When the lights were off and the building had settled into the creaks and sighs of night, I lay staring at the ceiling. Somewhere down the hall, someone laughed at something on a late-night show. Somewhere, a coffee maker burbled to life.

Tomorrow, a stranger would ask me to remember lists of words and draw clocks and repeat numbers backward. They would turn my life into scores on a page.

For the first time in my long career around sickness and death, I wasn’t afraid of dying. I was afraid of passing every test perfectly and still losing the right to choose what “living” meant for me.

Part 3 – Choosing a Home Instead of a Room Number

The test that was supposed to measure my mind felt less like medicine and more like a quiet little trial, with everyone waiting to see if I was guilty of being old.

Hawk drove me to the hospital in a borrowed van that rattled every time we hit a pothole. Rey rode in the back, pretending to scroll his phone, but I could see him watching me in the reflection of the window. Liberty House shrank in the rearview mirror until it was just another brick building in a row of brick buildings, easy to miss if you didn’t know what was inside.

“Last chance to bail,” Hawk said lightly as we pulled into the parking garage. “We can turn this thing around and go get pancakes instead.”

I smoothed the fabric of my coat over my knees. “If I run from a memory test,” I said, “he’ll use it as proof I can’t make decisions. I’d rather face the clipboard while I can still spell ‘clipboard’.”

Rey laughed once under his breath. “You’re going to make them all look slow, Doc,” he said. “You’ve got this.”

The building was just another public hospital, beige walls and gray floors and posters about handwashing that nobody really read. But I felt my stomach tighten the way it used to before I walked into an operating room for a case where everything could go wrong. Families sat on molded plastic chairs, clutching coats and coffee cups, eyes fixed on doors that might bring news.

Daniel was already there.

He stood when he saw me, smoothing his tie, his face a tired mix of relief and irritation. Beside him, his wife Lena wrapped her cardigan around herself like armor. A woman with a clipboard and a visitor badge waited near them, watching with professional interest.

“You came,” Daniel said, as if he hadn’t spent half of yesterday convinced I’d be running off with strangers and forgetting my own name.

“I did,” I said. “I keep my appointments, even the ones I didn’t make myself.”

The woman stepped forward and offered her hand. “Mrs. Ross? I’m Karen, the social worker assigned to your case today. I’m here to make sure you understand everything and to answer any questions.”

“I understand more than people think,” I said, shaking her hand. “But I appreciate the courtesy.”

We sat in a small conference room that smelled faintly of old coffee. A clock ticked loudly on the wall, each second sounding like a countdown. Karen explained the process in calm, practiced tones.

“You’ll meet with Dr. Patel, our neuropsychologist,” she said. “He’ll do some memory and thinking tests. It doesn’t hurt, but it can be tiring. Afterward, we’ll talk about what the results mean. The goal is to see what supports might help you stay safe and independent as long as possible.”

“Independent,” I repeated. “Good word. I like that one.”

Daniel shifted in his seat. “We’re not trying to take over, Mom,” he said. “We just… need information. To plan.”

“You scheduled a van for a place I haven’t seen,” I replied. “That feels less like planning and more like shipping.”

“Okay,” Karen cut in gently. “Let’s focus on today. Mrs. Ross, do you feel pressured to be here?”

I thought about it. “Pressured?” I said. “Yes. Forced? No. I chose to walk in the door. I’m still making that choice.”

She nodded and made a note. “Thank you. That matters.”

Dr. Patel came in a few minutes later, a man in his fifties with kind eyes and a tie that had tiny bicycles on it. It seemed like a deliberate choice, something to look at besides his face while he told people things they didn’t want to hear.

“We’ll talk for a bit,” he said. “Then we’ll do some puzzles and memory tasks. If you get tired, we can take a break. This isn’t about passing or failing. It’s about understanding how your brain is working right now.”

“I’ve spent my life looking at other people’s organs,” I said as he led me to a smaller testing room. “It seems fair to let someone look at mine.”

He smiled. “That’s a healthy attitude.”

The next hour was a strange parade of small humiliations and small victories.

He asked me to remember a list of words and repeat them back. I aced the first round, stumbled on one in the second, and lost two by the third. He asked me to draw a clock and set the hands to a particular time. My circle was a little shaky, but the numbers were in the right places, and the hands knew where to point.

He read me a story and asked me questions about it. He tapped out sequences of numbers and had me say them backward. At one point he showed me a page full of pictures and asked me to name what I saw.

“That’s a chair, a tree, a key, a… pigeon,” I said, squinting.

“Close,” he replied. “It’s a dove, but I’ll give you that.”

When he asked me to subtract seven from one hundred and keep going, I felt my jaw tighten. “We made pilots do this once coming off long shifts,” I said. “It wasn’t fair to them either.”

He chuckled. “You can complain about my methods,” he said, “but I still have to do them.”

By the time we finished, my head buzzed with numbers and half-remembered words. I felt like someone had shaken my brain and was now waiting to see what fell out.

Dr. Patel walked me back to the conference room. Daniel looked up anxiously; Lena’s hands were folded so tightly her knuckles were white. Hawk and Rey sat against the far wall, trying to look inconspicuous and failing.

“How’d it go?” Rey mouthed.

“I didn’t forget your face,” I mouthed back. “That seems promising.”

We all sat, and Dr. Patel took a breath that told me he’d had this conversation many times, in many ways, with many families.

“Mrs. Ross,” he said, “overall, your testing shows what we’d expect for someone with your age and history. Your education and career have given you a very strong foundation. You do show some mild weaknesses in short-term memory and attention, but your reasoning, language, and judgment are intact. You meet criteria for mild cognitive impairment, not dementia.”

“Mild,” I repeated. “Like salsa in the grocery aisle.”

He smiled faintly. “It means you’re at higher risk of developing dementia in the future, but you are currently capable of understanding information and making decisions about your life. That’s important. From a legal perspective, you still have capacity.”

Daniel let out a breath like someone had cut a rope. “So she’s fine?” he said.

“She’s not ‘fine’ in the sense that we can ignore the changes,” Dr. Patel replied. “She’s fine in the sense that she doesn’t need anyone taking away all her choices. What she needs is support, routine, and honest planning.”

Lena spoke for the first time, her voice tight. “But what about the stove and the fall?” she said. “If something happens when no one’s there, we’re responsible.”

“That’s where safety measures come in,” he said. “Stove alarms, medication reminders, regular check-ins, maybe some in-home help. A memory care facility can be an option eventually, but it shouldn’t be the first or only tool.”

“So your report will say she doesn’t need guardianship?” Daniel asked.

“My report will say she has the right to participate in those decisions,” Dr. Patel said. “If you pursue guardianship right now, it would be very hard to justify. And,” he added gently, “it could damage your relationship in ways that are difficult to repair.”

All eyes shifted to me. It was an odd feeling, being both subject and observer in my own life.

“I appreciate you not declaring me a lost cause,” I said.

“You’re not a cause at all,” he replied. “You’re a person. I’d like to see you in six months for a follow-up. In the meantime, I recommend you meet with a social worker to set up supports that you choose.”

Karen nodded and slid a folder across the table. “There are options besides moving this quickly into residential care,” she said. “You can combine community programs, home safety tools, and help from family or neighbors. What matters is that the plan is something you can live with.”

Daniel stared at the folder like it was written in another language. “I just wanted you to be safe,” he said to me. “I didn’t mean to make you feel… discarded.”

“You didn’t just make me feel it,” I said. “You made it literal, Daniel. You left me on a bench and drove away. A text message is not a conversation.”

His face crumpled in a way I hadn’t seen since he was a teenager and his first serious relationship ended. “I panicked,” he said. “You forgot the stove twice in one week. You fell and didn’t tell me. I kept imagining getting a call from the police saying they’d found you wandering, or from a hospital saying it was too late. The facility seemed… controlled. Predictable. I thought if I just handled it, it would be easier on you.”

“Easier on you,” I corrected gently.

He nodded, no defense left. “Easier on me,” he admitted.

Hawk cleared his throat. “I’m not family,” he said, “so I’ll shut up if you want me to. But as someone who has had people make choices about my life without asking me first—consider this. Fear makes people grab, not ask. You grabbed.”

Daniel looked at him, then at me. “What do you want, Mom?” he said. “If you don’t want the facility, what do you want?”

The question was so simple and so rare it stunned me for a moment. No one had asked me that without a list of acceptable answers already prepared.

“I want to live around people who know my name because I told it to them,” I said slowly. “Not because it’s written on a chart. I want help I agree to, not help dropped on my doorstep with a van schedule. I want to be somewhere that expects me to contribute, not just exist until my room is needed for someone else.”

“And where is that?” he asked, almost afraid of the answer.

I thought of Liberty House. The crooked pictures on the walls, the bad coffee, the way Rey’s eyes had filled when he recognized me. The way Hawk said “we” when he talked about making sure no one was left on a bench again.

“Right now,” I said, “that’s a small room down the hall from a kitchen that smells like chili and second chances.”

“You want to live… with veterans?” Lena said slowly.

“I want to live with people who understand what it means to come home from battles and still not feel safe,” I replied. “Some of those battles were overseas. Some were in hospital corridors. Some were in living rooms.”

Karen looked from me to Daniel. “There’s no rule that says an older adult has to live with their children to be loved,” she said. “You can support your mother’s choice and still set boundaries. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing.”

Daniel rubbed his eyes. “So you’ll stay there? At that center?” he asked.

“For now,” I said. “On my terms. I’ll pay what I can. I’ll do what I can. If a day comes when I truly can’t decide, then we’ll talk about other options. But I will not be stored away because it’s more convenient for your calendar.”

He flinched at the word “stored.” I didn’t apologize.

“I don’t know how to do this,” he said quietly. “Any of it.”

“Neither do I,” I admitted. “But I know how to hold a line when it matters. I’ve done it in worse conditions.”

In the silence that followed, the clock on the wall kept ticking, counting out the seconds of a life I suddenly felt very protective of.

Walking back through the lobby, my legs felt shaky but oddly lighter. Hawk walked beside me like a quiet wall. Rey walked a few steps ahead, as if clearing a path.

Outside, the air bit at my cheeks. The parking lot stretched out in front of us, rows of cars glittering in the pale winter sun.

“Do you want us to drop you at your apartment?” Hawk asked. “Or back at Liberty House?”

I looked at the elevator that led up to my small, quiet place with its forgotten stove and too-loud clock. Then I looked at the van with the dented door and the Liberty House bumper sticker peeling at the corner.

“Take me home,” I said.

“Which one is that?” he asked.

“The one where people waited for me to come back,” I replied.

Hawk nodded once, understanding. As the van doors closed, I saw Daniel standing on the curb, folder under his arm, watching us drive away. He lifted a hand, uncertain, halfway between a wave and a surrender.

I lifted mine back, not as a goodbye, but as a promise.

For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t just being taken somewhere.

I was choosing where I would fight for the rest of my life to still be mine.

Part 4 – The Doctor of Liberty House

Liberty House didn’t look like much from the outside, but inside it felt like somebody had taken all the frayed edges of people the world didn’t know what to do with and stitched them into one long, uneven, stubborn thread.

The front room was busier than the day before. A coffee maker hissed in the corner. A TV on the wall played the news with the sound off. A man in a wheelchair was arguing with another man about whether a particular song counted as “real rock” or not.

Hawk dropped my small bag by the door of the room they’d given me. “Rent is whatever you can afford,” he said. “We keep a little chart to make the grant people happy, but nobody’s going to shake you down.”

“I’m not looking for a free ride,” I said. “I’ve been paying my own way since before you were out of boot camp.”

He smiled. “We figured. That’s why we were willing to give you a key.”

The room was the same as the night before—narrow bed, old dresser, quilt made of other people’s lives. This time, though, there was a hook on the wall with my name written on a piece of tape above it. Someone had taken the time to write “Dr. Ross” in neat block letters.

“That’s… fast,” I said.

Rey leaned in the doorway. “We had a debate whether to put ‘Doc’ or ‘Dr.,’” he said. “The consensus was you earned all the letters.”

I hung my coat on the hook and sat on the bed. My apartment keys felt heavy in my pocket. They’d used to mean independence. Now they felt like a set of tiny anchors.

“I’m not a veteran,” I said. “You know that. I wore the uniform, but I never carried a weapon. I slept under canvas, but I went home to a real house after every deployment. This place is for people who… bled in ways I didn’t.”

“You think you didn’t bleed?” Hawk asked. “You think stitching up kids with shrapnel and sending them back out didn’t rip you up a little every time?”

“It wasn’t the same,” I said stubbornly.

“No,” he agreed. “But it was the same war. We all got hit by pieces of it. You get to sit at this table same as the rest of us.”

Word spreads fast in small communities, and Liberty House was no exception. By evening, everyone seemed to know some version of my story: old doctor, son, text message, bench. People drifted over in twos and threes, not crowding, just… orbiting.

A woman with short hair and a service dog sat next to me at dinner. “I’m Tasha,” she said. “Army, logistics. This is Ranger. He thinks he works here.”

I scratched the dog behind the ears. He leaned into my hand like he’d been waiting his whole life for someone to do that exact thing. “I’m Evelyn,” I said. “I used to yell at surgeons for standing too close to my sterile field.”

Tasha grinned. “Bet you were good at it,” she said. “Hawk says you’re a heart person. We’ve got a guy here who keeps skipping his meds because he ‘feels fine.’ Maybe you can scare him straight.”

“I don’t do scare anymore,” I said. “I do explain. And nag, if necessary.”

It started with a simple thing.

I watched one of the older men—Tom, Navy, Vietnam—open his pill bottle and shake out a handful like they were peanuts. He swallowed them dry, wincing, then chased them with coffee.

I couldn’t help myself. “Can I see that bottle?” I asked.

He handed it over without protest, the way people do when they’re used to strangers in white coats. The label was familiar. Blood pressure. Once a day. Not a handful.

“You’re taking too many,” I said. “By about four.”

He shrugged. “Doc at the clinic gave me three different bottles,” he said. “I just put ’em in one so I wouldn’t lose ’em. Figured more was better than less.”

“Not with this one,” I said. “More with this one can put you on the floor.”

I found an empty plastic container in the kitchen and sat down with him. We counted out a week’s worth into little piles while he told me about the time a wave almost washed him off the deck of a ship and he decided the ocean was rude and not to be trusted.

Word went around: Dr. Ross will help you untangle your meds. By the end of the week, I had a line. I didn’t change doses. I didn’t play hero. I just read labels, asked questions, wrote things down in big, legible letters, and told them to bring any concerns back to their own doctors.

“You know you’re doing half my job,” Hawk said one afternoon, watching me rearrange another plastic organizer. “In about three months, they’re going to forget how they ever lived without you.”

“I’m just making sure they live long enough to annoy you,” I said.

That’s how I met Mia.

She hovered in the doorway of the common room, a skinny girl in a thrift-store jacket, dark hair in a messy bun, phone in one hand like it was an extra limb. She watched me for a long time before stepping closer.

“You’re the doctor,” she said.

“I used to be,” I said. “Now I’m more of a… medication traffic controller.”

“That’s still a doctor,” she replied. “I’m Mia. My mom sleeps down the hall with the door open. Hawk says that’s so we can pretend we’re not really staying here.”

There was no resentment in her tone, just a flat kind of honesty that made my chest tighten.

“School?” I asked.

“Online when I can, in person when the bus and Mom’s anxiety line up,” she said. “I’m better with cameras than classrooms.”

She lifted her phone as if to prove it. The screen showed a video app, thumbnails of little vertical clips with millions of tiny hearts and comments scrolling too fast to read.

“I make videos about life here,” she said. “Nothing that shows faces unless people say it’s okay. Just… real stuff. People forget we exist if we don’t show up on their screens.”

I thought about the way the hospital lobby had been full of posters about heart disease and flu shots and nothing about what happened to the people who came home and couldn’t sleep without nightmares.

“You mind if I talk about you?” she asked. “Hawk told me what happened. The text. The bench. The whole… thing.”

“You want to film my humiliation?” I asked dryly.

She shook her head. “I want to film your survival,” she said. “You’re like… proof that it’s not just young people getting pushed aside when they’re inconvenient. It’s everybody. And that sometimes, they get picked back up.”

I sat with that for a moment. There was a part of me that wanted to say absolutely not, that my life was not a story for strangers to consume with their morning coffee. But there was another part, the part that had spent years teaching residents, that believed stories saved people when statistics didn’t.

“What would you record?” I asked.

“Your hands,” she said instantly. “They shake, but they still do things. The pill boxes. The list you made for Old Man Tom. Maybe your voice, if you’re okay with that. Not his name. Not your son’s name. Just the idea that you gave your life to a system and to a family and still ended up outside a grocery store with two bags and a text.”

“That sounds brutal,” I said.

“It is,” she replied. “But it’s also… hopeful. Because the video doesn’t end on the bench.”

I looked down at my hands. The tremor was there, small but insistent, like a tiny metronome keeping time on my skin.

“You blur my face,” I said. “No names. No hospital logos. No ranting about specific facilities. I won’t be used to attack people, Mia. I’ll only be used to remind them to look twice at their own families.”

She nodded solemnly. “Deal,” she said.

We filmed in pieces over the next few days.

She got a shot of my hands lining up Monday through Sunday, little clicks as each compartment closed. She filmed my feet in their sensible shoes walking from room to room. She asked me to talk about the first time I realized people were afraid of what age does to a brain.

“I was still practicing,” I said into her lens. “A nurse whispered about a patient, ‘She doesn’t even know where she is.’ The patient grabbed my wrist and said, ‘I know I’m someplace where I don’t matter.’ That scared me more than any diagnosis.”

Mia edited late into the night, headphones on, face lit by the glow of her screen. I saw snippets as she went: my hands, Ranger’s head in my lap, a close-up of the text message (with my son’s name carefully cropped out), the Liberty House sign in its peeling blue.

She added simple captions in white letters.

“She saved lives in a war zone.”

“She raised a son alone.”

“He tried to send her away with a van and a clipboard.”

“Strangers brought her home instead.”

When she finally showed me the finished video, my stomach twisted. “People are going to have opinions,” I said.

“People already have opinions,” she replied. “This just gives them a mirror.”

She posted it with a short description:

“Elder abandonment is real. So is found family. We’re Liberty House. We don’t leave people on benches.”

She didn’t tag any organizations. She didn’t mention the city. She let the story stand on its own.

Within an hour, it had a few hundred views. By dinner, it had ten thousand. By the time I went to bed, the little number at the bottom of the screen had grown enough that my brain stopped being able to process it as humans and just saw it as a wave.

Mia read comments aloud in the common room like a bedtime story for the disbelieving.

“My dad did this to my grandma,” one read. “I wish she’d had a place like yours.”

Another said, “I work in a nursing home. Not all of us are villains, but this hit hard. We’re full. Families are desperate. Systems are breaking.”

Of course there were ugly comments too. People saying I must have been a terrible mother. People accusing Liberty House of “collecting sympathy for donations.” People telling Mia to stop making “sad content for likes.”

She looked at me after reading those and rolled her eyes. “The internet is loud,” she said. “It doesn’t always mean it’s right.”

The morning after, I was sipping my coffee and trying to decide whether my knees hurt enough to justify another pill when Hawk came over with his own phone held out.

“You’re famous,” he said. “At least in a three-minute radius.”

On his screen was an email, addressed to the general Liberty House address. The subject line read:

“Local human interest story – inquiry about Dr. Ross and veteran community.”

In the body, a reporter introduced herself, said she’d seen the video, and wanted to do a piece about “an informal network of veterans caring for one of their own in a country that often forgets both.”

Hawk looked at me over the top of the phone. “We can ignore it,” he said. “Hit delete. Pretend it never came.”

The cursor blinked on the open reply window, as if daring us to do something with it.

For the second time in as many weeks, I found myself staring at a screen that had the power to send my life down a very different road.

“You once told me you don’t walk past people who’ve been left behind,” I said. “Maybe it’s time I stop walking past myself.”

Hawk didn’t smile, exactly. But something softened at the corners of his eyes.

“So,” he said, “do we invite the cameras in, Doc? Or do we keep this our little secret?”

Part 5 – When the Story Hit the News

I didn’t sleep much that night.

Every time I closed my eyes, I saw screens. The small one in my hand with Daniel’s message. The bigger one in Mia’s, full of comments from strangers. The one in Hawk’s, holding that email like a door half open.

In the dark, Liberty House creaked and sighed like an old ship. Someone down the hall coughed. Ranger’s tags jingled once as he turned in his sleep. I lay on my back and listened to a building full of people who had not been allowed to break in private.

If a reporter came, our breaking would be public.

By morning, my mind had slipped into its old surgeon’s mode. List. Triage. Decide. If I thought about this as “exposing my family,” I’d say no. If I thought about it as “telling the truth about how we treat people when they’re inconvenient,” I had trouble staying quiet.

At breakfast, the question hung in the air with the smell of burned toast.

Mia pretended to scroll her phone, but her shoulders were tight. Tasha kept refilling the coffee pot by half cups, as if stalling. Tom pushed his eggs around his plate.

“You all look like you’re waiting for a test result,” I said.

“In a way, we are,” Hawk replied. “This reporter thing? It affects all of us. Not just you.”

“I know,” I said. “Which is why I don’t get to decide alone.”

They stared at me, surprised. I suppose they weren’t used to older people being the ones insisting on shared decision-making.

“I have conditions,” I continued. “If we do this, they don’t get to turn us into a tragedy parade. No faces filmed without consent. No names for people who don’t want them used. No blaming one son as if the whole culture doesn’t make it easy to push aging parents out of sight.”

Mia let out a breath. “So… yes?” she asked cautiously.

“Yes,” I said. “On our terms. Or not at all.”

Hawk nodded. “Then we invite her,” he said. “And we tell her that up front.”

The reporter’s name was Julia.

She came two days later, driving a small hatchback that had seen better suspensions. Her hair was pulled back in a functional knot. She wore boots that said she’d walked more parking lots than red carpets.

When she stepped into Liberty House, she stopped just past the threshold and looked around slowly, not like a tourist, but like someone taking stock.

“Thank you for letting me in,” she said. “I know I’m a stranger. I’d like to leave here less of one.”

“We’ll see,” Hawk said. “Depends how you write.”

She smiled at that, a quick flash. “Fair enough,” she said.

We sat at the big table that had seen more late-night card games than serious interviews. Mia hovered nearby with her camera in her pocket, not filming, just listening.

“I saw the video,” Julia said, turning her attention to me. “I wanted to follow up because it felt… unfinished. Like there was a much bigger story under it.”

“It’s a very old story,” I said. “We just gave it a modern format.”

She clicked her pen. “If you’re comfortable, I’d like to hear it in your words,” she said. “No pressure. We can stop anytime.”

I told her about Daniel.

Not just the text in the parking lot, but the years before that. The soccer games I missed because a trauma case came in. The nights I slept on a cot in a hospital call room while he did homework at a neighbor’s house. The way he used to wait up and fall asleep on the couch with the TV on, the volume low, so he’d hear my key in the door.

“I thought putting a roof over his head and food on the table was love,” I said. “I still think it was part of it. But I didn’t always have energy left for the softer parts. The bedtime stories. The school plays. I told myself, ‘I’ll be there next time,’ until one day there weren’t any next times.”

Julia took notes, but she also watched my face. That told me more than her questions.

“Do you think he abandoned you because he doesn’t love you?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I think he loves me in a scared, practical, exhausted way. The way a lot of people love aging parents they don’t know how to keep safe and also keep their own lives from collapsing. Fear and love make strange bedfellows.”

Mia made a small sound at that, half laugh, half sigh.

We talked about Liberty House. How it started as a weekly support group in a church basement and grew into a building because no one could bring themselves to say goodbye after an hour. How grants and donations patched the holes the way duct tape patched the furniture.

“Are you worried people will accuse you of exploiting Dr. Ross’s story for funding?” Julia asked Hawk.

“People already accuse us of existing wrong,” he said. “If telling the truth about how we take care of our own brings in enough help to fix the roof, I can live with their comments.”

She wanted to talk to others too. Some agreed. Some shook their heads and walked away. Julia respected both answers.

Tom told her about losing his apartment when his roommate died and the rent doubled. Tasha told her about panic attacks in crowded stores. Mia, unexpectedly, sat down and told her about homework done in motel rooms and the way her mother flinched at loud noises.

“Everyone thinks veterans are scary,” Mia said. “They don’t talk about how scared veterans are of everything that isn’t a war.”

At one point, Julia looked at me. “What do you want people to feel when they read this?” she asked.

“Torn,” I said. “Because this isn’t a simple story where my son is the villain and the veterans are the heroes. It’s about a system that leaves all of us improvising with people we love and people we barely know.”

She scribbled that down. “Can I quote you?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “You can quote anything that doesn’t make me sound kinder than I am.”

Lena would have laughed at that line. I wondered if she’d read the article. I wondered if she’d see herself in it.

Before Julia left, she asked a practical question. “Do you want to use your full name?” she said. “Some people prefer initials.”

I thought about hiding. Then I thought about Mia’s caption: Elder abandonment is real. So is found family.

“Use it,” I said. “I’ve put my name on harder things.”

She nodded. “We’ll keep your son and his family anonymous,” she said. “The point is the pattern, not the pile-on.”

When she drove away, Liberty House felt strangely quiet. We’d let someone from the outside see the cracks. Now we had to wait and see what she did with them.

The piece came out three days later on the local paper’s website, tucked between an article about a school board meeting and one about a new grocery store opening across town.

Mia found it first.

She burst into the common room with her phone held high. “It’s up,” she said. “You’re going to want to sit for this.”

The headline read:

“‘We Don’t Leave People on Benches’: Veterans Create Safety Net for Aging Doctor.”

The photo showed my hands on a pill organizer, Ranger’s nose nudging my elbow. My face was out of frame. Hawk and Maya were blurred in the background, laughing at something just out of sight.

The article was… better than I’d dared hope.

Julia told my story without turning me into a saint or a cautionary tale. She wrote about Daniel, but as “her only son,” not as an object of public scorn. She wrote about Liberty House as a messy, imperfect answer in a country where the questions about aging and care were piling up faster than answers.

She included quotes from me, from Hawk, from Tasha, from a social worker who talked about “supporting capacity rather than defaulting to control.” She linked, at the end, to resources for caregivers and older adults.

The comments under the article poured in. Some were simple: “Thank you for writing this.” “Crying at my desk.” Some were more pointed: “We need more places like this.” “We need policies that don’t force families into impossible choices.”

Daniel texted me two hours after the article went live.

You went to the paper.

There was no greeting. Just those six words, pulsing on my screen like a heartbeat.

I stared at them for a long time before responding.

She came to us. I agreed because this isn’t just my story.

His reply came quickly.

People at work recognized it. They’re asking questions. They think I’m the son who left his mother in a parking lot.

Are you more worried they think it than that you did it?

There was a longer pause this time.

That’s not fair.

Neither was the bench.

No dots appeared. No typing. The silence grew until it felt like a presence sitting beside me.

At dusk, the front door opened.

Daniel stepped in, looking smaller in Liberty House than he did in his own living room. His tie was loosened. His eyes had that red-rimmed look people get when they’ve been reading the same thing over and over, hoping the words will change.

“I thought we were going to figure this out privately,” he said without preamble.

I set my mug down carefully. “Privacy ended the moment you made decisions for my life without me,” I said. “This article doesn’t name you. It names what’s happening to people like me. And people like you.”

He glanced around the room, taking in the mismatched chairs, the bulletin board, the photo wall. There was suspicion in his gaze, but also something like curiosity.

“So this is it,” he said. “The place you chose over your own family.”

“No,” I corrected. “This is part of my family. The part that picked me up when the other part set me down. You and I are not over, Daniel. But we can’t start again if you keep pretending this is just about one bad day.”

He looked at Hawk, hovering at the edge of the conversation like a very solid, very present boundary.

“And you,” Daniel said. “How convenient that a tragic story walks into your building right when you need donations.”

Hawk didn’t flinch. “We needed donations before your mother showed up,” he said. “We’ll need them after. We didn’t write that article. We just stopped hiding what’s already happening.”

“You’re using her,” Daniel snapped. “The video, the piece, the comments. You’ve turned my mother into content.”

Mia bristled, then forced herself to stay quiet when I put a hand on her arm.

“No one here put words in my mouth,” I said. “I chose what to say. I chose who to say it to. That’s more choice than I had on that bench.”

Daniel opened his mouth, then closed it again. His shoulders slumped, the fight leaking out of him in a slow exhale.

“I feel like I’m losing you,” he said, voice cracking. “Like every step you take closer to this place is a step away from me.”

“You’re losing the version of me that went along with things to keep the peace,” I said. “The one who smiled and said, ‘Whatever you think is best, dear,’ while swallowing the parts of myself that were still very much alive. That’s the only version you ever made room for.”

He rubbed at his chest distractedly, fingers pressing near his collarbone as if his shirt had suddenly become too tight.

“I’m trying to make room now,” he said. “I came, didn’t I? I walked in. I’m here.”

“That matters,” I said. “But you’re still standing in the doorway, Daniel. You haven’t sat down yet.”

He took a step toward the table, then stopped. His breath hitched. His hand pressed harder into his sternum.

“Are you all right?” I asked, my old instincts snapping awake.

“I’m fine,” he said automatically, but his voice was thin. “Just… long day. Too much coffee.”

He took another step and the color drained from his face. A sheen of sweat broke out along his hairline. He blinked slowly, like the room was tilting.

“Daniel,” I said sharply. “Look at me.”

His eyes met mine, unfocused. “I don’t…” he started, then his knees buckled.

The mug in my hand hit the floor and shattered, coffee spattering my shoes. Everything else narrowed down to him.

“Call 911,” I barked, my voice cutting through the room like a scalpel through noise. “Now. Tell them possible cardiac event, male, mid-forties, history of stress. And get me an aspirin if we have one.”

Hawk was already moving, phone in his hand. Rey grabbed a pillow for Daniel’s head. Tasha cleared the table of clutter in one sweep in case we needed space.

I knelt beside my son on the worn-out rug of Liberty House, my fingers finding his wrist, my training sliding into place like it had just been waiting for permission.

My son, who had tried to decide where I would spend the rest of my days, was suddenly utterly, terrifyingly in my hands again.

Part 6 – His Heart Attack in the Middle of an Argument

I hadn’t been a practicing trauma surgeon for years, but my hands didn’t seem to know that.

Daniel’s pulse under my fingers was fast and thready, his skin clammy. His eyes fluttered, unfocused, like he was struggling to swim up through thick water. I tilted his head, watched his chest, counted the seconds between breaths.

“Ambulance is on the way,” Hawk said from somewhere above me. “They’re three minutes out.”

“Feels longer,” I muttered.

Tasha knelt on Daniel’s other side, her calm a solid presence. “You want him on his back or his side, Doc?” she asked.

“Flat for now,” I said. “If he vomits, we roll. Someone get an aspirin tablet if there’s one in the med cabinet. Not a handful. One.”

Rey sprinted down the hall, skidding a little on the worn linoleum. I focused on Daniel’s face.

“Daniel,” I said, my voice low and sharp. “It’s Mom. Squeeze my hand.”

His fingers twitched weakly around mine.

“I need more than that,” I said. “Pretend you’re thirteen and I just told you to wake up for school.”

His mouth curved, just barely. “Five… more… minutes,” he whispered.

“Good,” I said, the breath I hadn’t realized I was holding slipping out. “Stay in this world, then. The other one is overcrowded.”

Rey came back with a small white tablet and a paper cup of water. We got it between Daniel’s lips, coaxed him to chew, then let him sip enough to wash it down. The seconds dragged, each one a tiny anchor in my chest.

Sirens wailed in the distance. The room shifted around us as people moved furniture, cleared paths, did what they always did at Liberty House—made space in the chaos.

The EMTs burst through the door, uniforms crisp, faces serious. For a moment, they saw only a middle-aged man on the floor of a shabby community room and an old woman kneeling beside him.

“I’m Dr. Ross,” I said before they could decide my role for me. “Retired trauma. He’s my son. Sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, near-syncope. Brief altered consciousness, improved with rest. Aspirin on board five minutes ago. Pulse rapid, skin cool and diaphoretic.”

One of them, a woman with tired eyes and a messy ponytail, nodded sharply. “Got it,” she said. “Thank you, Doc. We’ll take it from here.”

They moved with the practiced efficiency I used to see in my own teams. Oxygen, ECG leads, blood pressure. Questions about history, meds, stress.

“Any known heart conditions?” she asked.

“None diagnosed,” I said. “Family history of coronary disease on his father’s side. Stress like a second job.”

Daniel tried to sit up. “I’m okay,” he muttered. “I just stood too fast.”

The EMT gave him a look that would have done any operating room nurse proud. “Sir, the last guy who told me that flatlined in the elevator,” she said. “We’re not risking that. Lie still.”

They loaded him onto the gurney. As they wheeled him toward the door, Daniel’s hand reached out blindly.

“Mom,” he said. “Don’t… don’t be mad.”

The words hit harder than any lab result.

“I’m not mad,” I said, walking alongside him. “I’m here. That’s all that matters right now.”

Hawk put a hand on my shoulder. “We’ll follow,” he said. “You’re not doing this alone.”

The ride to the hospital was a blur of flashing lights and sirens that felt too familiar. I sat in the passenger seat of Hawk’s van, knuckles white on the armrest, while Rey drove faster than he probably should have.

“You okay back there?” I called over my shoulder.

Hawk snorted softly. “Doc, you’ve patched me up after worse,” he said. “I’m just driving the worry bus this time.”

The emergency department was busy, as they always are, but the ambulance siren carved us a path. They took Daniel straight to a bay, curtains drawn around him like a temporary wall between the world and our fear.

A nurse tried to usher me to the waiting room. “We’ll let you know as soon as the doctor has news,” she said, voice kind but firm.

I met her eyes. “I’ve spent four decades being the doctor with news,” I said. “I know how this works. I won’t get in your way. Let me stand at the edge.”

She hesitated, then nodded. “Stay by the chair,” she said. “Don’t cross the line.”

I stayed by the chair.

I watched them draw blood, start an IV, adjust the monitors. The ECG trace flickered on the screen, a familiar wave. Not a full-blown catastrophe, but not nothing either.

“Likely NSTEMI,” the attending murmured to the resident. “We’ll get enzymes, call cardiology. He’s lucky he dropped where someone knew what they were seeing.”

Lucky. That was one word for it.

Lena arrived twenty minutes later, hair escaping its bun, jacket half on. Her eyes flew to the curtained bay, then to me.

“What happened?” she demanded. “He was fine. He texted he was going to talk to you and then—”

“He wasn’t fine,” I said gently. “He hasn’t been fine for a long time. Today his heart decided to say it out loud.”

She sank into the chair next to me. For a moment, she looked much younger, shadows under her eyes, hands shaking.

“Is this… my fault?” she asked. “For pushing him? For agreeing with the facility? For not fighting harder for you?”

Guilt loves easy targets. It had preyed on me for years. I recognized its claws in her voice.

“This isn’t a punishment,” I said. “He has a job that eats him, two kids, a mortgage, a mother who doesn’t fit neatly into the boxes the world offers. His heart got tired. Bodies speak when we don’t listen.”

She nodded, tears pooling but not falling. “He said he felt tight in the chest this morning,” she whispered. “I told him it was anxiety. I told him to breathe and drink water. God, what if—”

“You did what you could with what you knew,” I cut in. “So did he. So did I. Blame the pace we’re all running at, not just yourself.”

A man in scrubs parted the curtain. He was young enough to be one of my residents once, but he wore the mantle of responsibility like it was already heavy.

“Mrs. Ross?” he asked. “And… Mrs. Ross?” He looked between us, slightly confused.

“I’m his mother,” I said. “She’s his wife. Go ahead and confuse us. We’re used to it.”

He smiled briefly. “I’m Dr. Chang from cardiology,” he said. “Your husband—your son—had what we call a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. A mild heart attack, essentially. There’s no such thing as a ‘good’ heart attack, but if you’re going to have one, this is the kind we can usually work with.”

Lena let out a shaky breath. “Is he going to be okay?” she asked.

“He’s stable,” Dr. Chang said. “We’re starting medications to thin the blood and reduce the heart’s workload. We’ll do further tests to see if he needs a procedure to open any narrowed arteries. The most important thing now is lifestyle changes. Stress management. Follow-up care. He’s going to have to adjust how he lives.”

He glanced at me. “He mentioned you’re a retired trauma surgeon,” he added. “That tracks with his blood pressure.”

I snorted. “He blames me for everything,” I said. “Might as well add his cardiac risk profile to the list.”

Dr. Chang’s expression softened. “He also said you saved someone’s life before the ambulance arrived,” he said. “His.”

When we were finally allowed back to see him, Daniel looked smaller on the hospital bed than he ever had in my memory. Tubes and wires framed him, a plastic bracelet circling his wrist where I used to wrap my fingers around chubbier skin.

“Hey,” he said weakly when he saw us. “Guess I know what a wake-up call feels like now.”

“You always were dramatic,” I said, taking his hand carefully. “There are cheaper ways to avoid finishing a conversation, you know.”

He tried to laugh and winced. “Don’t make me do that,” he said. “It hurts.”

Lena stood on the other side of the bed, one hand on the rail. For a long moment, none of us spoke. Machines beeped. Nurses moved in and out. Life went on in fluorescent lighting.

“I saw the article,” he said finally, looking at me. “Read it twice. Then my chest started feeling… heavy. Like everything I’d been ignoring slid onto my sternum.”

“We’ll talk about that when your heart isn’t auditioning for a medical drama,” I said. “For now, just breathe.”

A knock at the door made us all look up.

Karen, the social worker from the evaluation day, stepped in. She had a clipboard again, but her smile was warmer than the beige walls deserved.

“I’m not here to add to your stress,” she said. “I heard you landed back in our hospital and thought I’d check on all of you.”

Daniel groaned softly. “Even my heart attack has paperwork,” he muttered.

Karen pulled a chair closer. “Actually, I wanted to suggest something that might help with the part of this that isn’t lab values and stents,” she said. “We have a family mediation program. Facilitated conversations for situations like yours—adult children, aging parents, big decisions, a lot of history. It’s not counseling in the therapy sense, more like… guided honesty.”

“Do we get gold stars if we don’t shout?” I asked.

“Sometimes,” she said. “Sometimes we just get through an hour without anyone walking out. Both can be wins.”

Lena looked at Daniel, then at me. “We didn’t exactly nail the first round of talking,” she said. “Maybe having a referee wouldn’t be the worst idea.”

Daniel closed his eyes for a second, then opened them again. “I thought I could manage everything,” he said. “Kids, job, you. Now my own heart is calling timeout. Maybe I’m not as in control as I thought.”

“That’s step one,” Karen said. “Recognizing the limits. Step two is deciding whether you want to keep trying to do this alone or let other people in.”

He shifted his gaze back to me. “Would you… be willing?” he asked. “To sit in a room with me and someone whose full-time job is to keep us from destroying each other?”

The way he phrased it almost made me smile.

“I’ve sat through worse meetings,” I said. “Army briefings. Hospital board arguments. I think I can survive one hour of us telling the truth.”

“And if the truth hurts?” he asked softly.

“Then it means it’s hitting something that needs to be touched,” I replied. “Pain isn’t always damage, Daniel. Sometimes it’s growth.”

He nodded slowly, eyes shining.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s… try it. Before my next mid-life crisis decides to involve more organs.”

Karen scribbled on her clipboard. “I’ll set it up when you’re stable enough,” she said. “We can hold it here or at a neutral location. Liberty House is welcome to send someone too, if you want support.”

The idea of Hawk in a mediation room made me huff a short laugh. “He has a talent for saying blunt things in gentle tones,” I said. “Could be useful.”

When Karen left, the room settled into a quieter kind of waiting. The crisis had passed, but the aftershocks were still humming in our bodies.

I watched my son drift toward sleep, the monitors reflecting his heart’s new, fragile rhythm. Somewhere between beats, I realized something simple and devastating.

For years, I had been terrified of becoming a burden. The word had loomed over every forgotten stove, every mislaid key. I’d let it drive me toward the very isolation that nearly killed both of us.

But burden and connection, I was starting to see, were not opposites.

Sometimes they were just two names for the same weight people chose to carry together.

Outside the window, the sky had started to shift toward evening, hospital lights bleeding into the dim. My phone buzzed in my pocket.

A message from Mia:

Heard about Daniel. We’re on standby if you need backup. Ranger says hospital floors are great for napping.

Another from Hawk:

You good, Doc?

I looked at my son, at his sleeping face softened by the kind of vulnerability no adult ever wants anyone to witness. I looked at Lena, slumped in the visitor chair, her hand still on the bed rail even in half-sleep.

Then I typed back.

Not good. But not alone.

For now, that was enough.

Part 7 – Hard Truths in a Hospital Conference Room

They moved Daniel out of intensive care two days later, which in hospital language meant, “We’re not afraid you’ll die today, just worried about all the tomorrows.”

He looked less like a ghost and more like himself, but the IV pole and the beeping monitor were constant reminders that his heart had drawn a line. The first time he tried to joke, he ran out of breath halfway through the sentence and glared at his own lungs. “This is humiliating,” he muttered.

“Welcome to the club,” I said. “Aging is just a long list of humiliations you learn to laugh at.”

Karen chose a small family conference room around the corner, the kind of space that had seen more tears than birthday cakes. There was a round table, four chairs, a box of tissues, and a painting of a sailboat that looked like it wanted to escape the wall.

She set her clipboard down and clasped her hands. “Ground rules,” she said. “No shouting, no name-calling, no bringing up old arguments just to win new ones. Speak from your own experience. If anyone needs a break, say so. This isn’t a trial. It’s a conversation with bumpers.”

Lena sat beside Daniel, angled slightly toward him like she could keep his heart beating by proximity. Hawk was on my side, a quiet solidity in a chair that seemed too small for him. I was absurdly grateful he’d agreed to come.

“I’m here as moral support,” he’d said. “And to remind you that whatever gets said in there, you walk out with more people than you walked in with.”

Karen looked at me. “Mrs. Ross,” she said, “you’re the one whose living situation is at the center of this. Would you like to start, or would you rather respond?”

I took a breath. Years of leading trauma teams had taught me that the hardest words are sometimes the simplest.

“I don’t want to be locked away,” I said. “I don’t mean nursing homes are evil. I mean I don’t want one chosen for me like I’m a piece of furniture. I want to feel like a person whose life still belongs to her, even if parts of it are fraying.”

Daniel stared at his hands.

“I left her on a bench,” he said, before anyone could prompt him. “I keep replaying it. I told myself I was being efficient, that I’d sign the paperwork and be back before she finished shopping. But part of me knew, when I drove away, that I was putting distance between myself and the thing I didn’t want to watch.”

“What thing?” Karen asked.

“Her getting smaller,” he said. “Forgetting things. Needing me. My whole life, she was this… unstoppable force. She ran ORs and field hospitals and an entire household by herself. I don’t know how to think about her any other way. Seeing her vulnerable scares me.”

“Being vulnerable scares me,” I said. “But I don’t get to walk away from it.”

He winced. “I deserve that,” he said.

Karen turned to Lena. “And you?” she asked gently. “What’s this been like for you?”

Lena rubbed her thumb along the edge of the table. “I grew up watching my mom take care of my grandmother at home,” she said. “We loved her, but it was… brutal. No help, no breaks, no money. My mom got sick from the stress. When she died, people said it was ‘just her time.’ I think the strain killed her as much as anything.”

She looked at me, eyes full of something that wasn’t quite apology and wasn’t quite defense.

“When Daniel started talking about you forgetting things,” she continued, “all I could see was that house again. Piles of laundry, unpaid bills, my mom crying in the bathroom with the water running so we wouldn’t hear. I told myself I would never live that way again. I overcorrected. I pushed for the facility because I thought, ‘We’ll have help this time. Professionals. Structure.’”

“And no one at your kitchen table,” I said quietly.

Her face crumpled. “I didn’t want you gone,” she said. “I wanted the fear gone. I thought if we outsourced the hardest part, maybe we could all breathe. I didn’t think about how it would feel to you to be… handled like a problem. I’m sorry.”

The word hung in the air like a fragile bridge.

“I believe you,” I said. “That you were scared. That you thought you were protecting everyone. But the way you did it made it very clear I was something to be managed, not someone to be met in the middle.”

Daniel cleared his throat. “I should have talked to you,” he said. “Sat down and said, ‘I’m scared. I don’t know what to do. Help me.’ Instead I made decisions in secret and pretended it was kindness. It was control.”

Hawk spoke for the first time. “Control masquerading as kindness is something a lot of us here know,” he said. “When I came back from my last deployment, they wanted to check me into a psych facility ‘for my own good.’ No one asked what actually made me feel safe. They just assumed they knew. It took me a long time to stop hearing ‘we’re worried about you’ as ‘we’re tired of dealing with you.’”

Karen glanced at him. “Thank you for sharing that,” she said. “It’s a useful parallel. Mrs. Ross, how did the evaluation results make you feel?”

“Relieved,” I said. “And terrified. Relieved because someone with authority said, ‘You still count.’ Terrified because I know that won’t always be true. There will come a day when my brain can’t pass those tests. I don’t want to pretend otherwise. I just don’t want that day used as an excuse to erase me early.”

Daniel looked up, eyes shining. “What do you want us to do when that day comes?” he asked. “Because pretending it’ll never happen isn’t a plan. I thought I was planning ahead. I wasn’t. I was panicking ahead.”

I thought about the grainy black-and-white scans I’d seen of brains over the years, about the way disease could hollow out a person from the inside while their body still moved through the world.

“I want a say in the plan while I still can give it,” I said. “If I get to a point where I’m truly a danger to myself, where I’m wandering or leaving the stove on constantly or forgetting who you are, then yes, maybe we talk about a place with locked doors. But I want it to be a place I’ve seen. A place I chose with you. Not a surprise.”

Karen nodded, jotting something down. “This is exactly the kind of conversation most families avoid until crisis forces their hand,” she said. “It’s painful, but it’s also an opportunity.”

“What about Liberty House?” Lena asked, turning toward Hawk. “What guarantees do we have that this place isn’t just… another emergency stop that becomes permanent without oversight?”

Hawk took that without flinching. “We’re not a licensed facility,” he said. “We’re a community center with some beds and a lot of coffee. We have rules. We do background checks. We work with social workers and clinics. But no, we don’t have a big agency logo on the wall. We have each other. That’s messy. It’s also kept people alive who would have fallen through every official crack.”

“What happens if you get hit by a bus?” she asked bluntly. “Or if funding dries up? Where does that leave her?”

“Scattered, probably,” he said, just as blunt. “But that’s why we’re talking to people like Julia. To shine a light, to maybe get more stable support. I can’t promise eternity. I can promise we’ll tell you if we’re in trouble instead of pretending everything’s fine while the ceiling caves in.”

I appreciated that more than any polished brochure.

Karen looked around the table. “Here’s what I’m hearing,” she said. “Evelyn wants to stay at Liberty House for now, with supports she chooses. Daniel and Lena are worried about safety and long-term stability. Everyone is afraid of losing each other in different ways. What we need is a written plan that spells out what ‘for now’ means, what would trigger revisiting that decision, and how you’ll handle crises.”

“You mean like a… contract?” Daniel asked.

“More like a roadmap,” she said. “With room for detours.”

We spent the next half hour drawing lines on paper. Regular medical check-ups. Follow-up neuropsych testing in six months. Stove alarms and a wearable fall detector for me, even if the idea made me bristle.

“I’ll wear it if it buzzes when I’ve been sitting too long,” I said. “Make it nag me into taking walks, not just into being pathetic.”

Lena actually laughed. It sounded rusty, but real.

Daniel agreed to visit Liberty House twice a month for dinner, not as a supervisor, but as family. I agreed not to ambush him with reporters. Lena agreed to come once, just to see the place, and reserve judgment until after she’d met more than two people in the doorway.

“And if your cognition declines significantly,” Karen said gently, “you agree to revisit the idea of a higher level of care, with your input as long as possible.”

“Yes,” I said, the word heavy but necessary. “But if that happens, you don’t get to dump me in whatever place has an opening. You bring me brochures. You take me to visit. You tell me the truth.”

“I can do that,” Daniel said softly. “I couldn’t put you on a stretcher if you begged me to, but I can bring you brochures.”

At the end, Karen made us all sign the paper. Not because it was legally binding, but because sometimes putting your name next to a promise makes it real.

Outside the room, the hospital corridor bustled with the same indifferent rhythm. People were born, diagnosed, discharged, all on the same linoleum.

Hawk walked with me toward the elevator. “You did good in there,” he said. “Didn’t throw a single tray.”

“I thought about it,” I said. “But I’m trying new coping strategies.”

My phone buzzed in my pocket. Another message from Mia:

Everything okay? Ranger’s staring at the door like he’s expecting someone.

Tell him to save the dramatic entrances for me, I wrote back.

We drove back to Liberty House under a sky that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be gray or blue. My body was tired, but my mind felt strangely clearer, like we’d lanced an infection that had been festering for years.

I expected to walk into the familiar smell of coffee and crockpot stew.