Part 5- 14–33: Notes Not Ready

I didn’t take the envelope to the police. I took it to my mother’s kitchen table.

We were never a dining room family. Big conversations in our house always happened with elbows on the laminate and a dish towel nearby. The leather jacket lay on the chair beside Mom like a quiet uncle at a reunion. Evan stood, because he always stood when rooms got tight. Liam hovered near the counter, pretending to study the fruit bowl like it might quiz him.

I slid the letter across the table. Mom read it once, then again, her mouth doing that small pressed line that meant she was disappointed in the world, not in me. Evan didn’t touch it. He looked out the window toward the backyard where Dad had hung a tire swing years ago and never took it down even after we all outgrew it.

“Clean story,” Mom said finally. “That’s not new.”

“It’s new to my mailbox,” I said. “And apparently to the shop door and to the city clipboard.”

Evan’s shoulder twitched, the closest he ever got to a shrug. “If stories are complicated, some folks hear noise. They chase quiet even if it’s the wrong kind.”

I took a breath I could use later as evidence I’d tried to be fair. “Then let’s make it complicated in a way the town can live with. Key first.”

The tag stamped 14–33 had been nagging me since the shop. Under Dad’s old desk in the den, near the scuff where his chair had always rubbed the wall, was a small metal box bolted to the floor. You could miss it if you wanted to. I didn’t.

The key turned like it recognized our family by grip.

Inside: two composition notebooks with black-and-white marbled covers, a thin stack of carbon copies from the plant office, and a cigar tin without cigars. The notebooks were labeled in Dad’s tidy caps. NOTES. NOT READY.

I opened the first.

He used his line foreman voice in ink—short, precise, no extra words chasing the edges. The entries were dated in the months before the press line went quiet.

“Maintenance cycle suggested 6 weeks. Approved 10. Supervisor notes say ‘cost pressure.’ Spoke up at meeting. Logged dissent in minutes. Copy here.”

“Vendor substitution on fasteners. Grade marked ‘equal.’ Spec sheet shows lower tolerance. Flagged. Told we’ll ‘monitor.’”

“Training hours cut. ‘Shadowing counts as training.’ Flagged. No response.”

On another page, written softer, like he’d set the pen down twice before finishing the thought: “Asked Evan to stay away for a while. Said his presence made me brave in the wrong room and quiet in the right one.”

I shut my eyes against that sentence and saw my father’s hands, big and patient, teaching me to measure once and cut twice because you are allowed to make mistakes if you know how to fix them. I saw those same hands, later, flat on our kitchen counter while he said words he did not believe because the room he had to belong to next required them.

The carbon copies were change orders and meeting notes and one memo about “temporary tolerance adjustments pending supplier issue.” There was a sign-off line for “Plant Management” with my father’s name typed and signed. Someone had circled the signature in pencil and written, “Only if inspection confirms safety.” The pencil matched Dad’s desk drawer—the one that always smelled like cedar and honesty.

The cigar tin held receipts paper-clipped to index cards. Gas. Hardware. Printer ink for the library. A receipt for five reflective vests bought with a coupon and a note in the margin: “Every little bit counts.” At the bottom of the tin lay a small photo of a parking lot chalked into lanes, early morning light making long shadows out of cones. Dad’s handwriting on the back: “First Saturday. Felt like something useful.”

Liam slid into the chair beside me without asking. “He was trying to fix it,” he said, not looking up from the notebook, like he’d climbed a tree and could suddenly see the shape of our block.

“He was also signing things that let it get broken,” I said, and the part of me that argues until the other person’s shoulders drop wouldn’t let the sentence soften.

Mom turned a page in the second notebook and stopped. “Here,” she said, tapping the margin with her finger. Her nail had a dent from washing dishes without gloves, a mark of a life that had not included spa days. “He wrote this the week before the press jam.”

The entry was spare. “Asked to approve extended run. Said no twice. Third time, said yes with conditions in writing. Conditions not attached to final print. Did not chase. Weakness comes dressed as pragmatism.”

No excuses. No villain cast in neon. Just a man admitting he’d chosen the path that didn’t trip the alarm.

Evan reached for the carbon copy stack. “He called me after that meeting,” he said, eyes on the past he could still hear. “Said he needed me to be a reason. I told him I’d be a wall if that’s what he needed. He said he hated walls.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“I stayed away,” he said. “Like the notebook says.”

The inside of my ribs felt too small. “Because you thought the sight of you made him act braver than the room could hold,” I said, finishing the thought out loud to prove I understood it and to punish it at the same time.

“Because he asked,” Evan said simply.

The phone on the counter vibrated again—the persistent hum of civic life. This time it was my boss, not texting. Calling. I let it ring twice, three times, then answered.

“Are you resting?” she asked without hello, the way people ask a question that isn’t about rest.

“In theory,” I said, watching my brother read our father’s penmanship like braille.

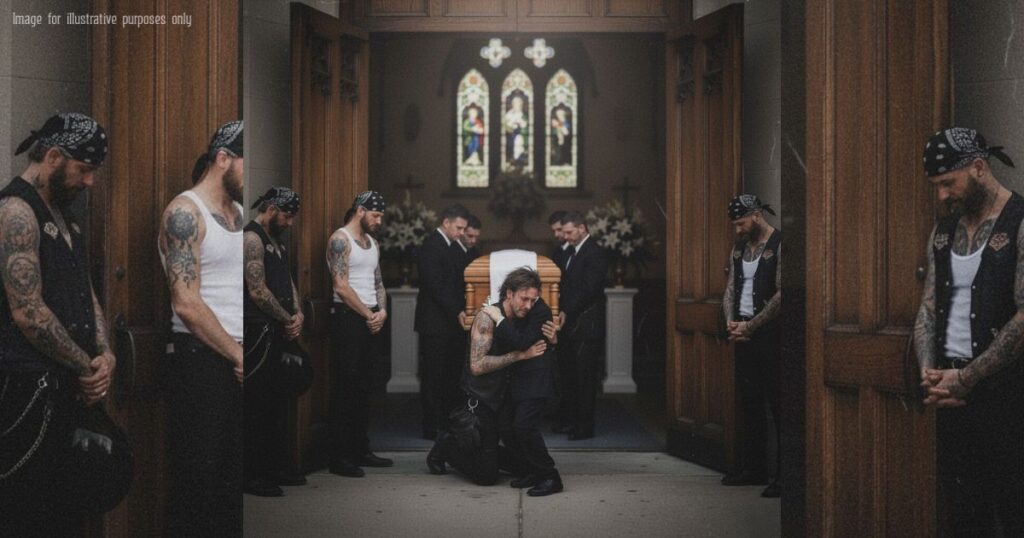

“I’m sorry to intrude on a hard day,” she said, and meant half of it. “We’re getting calls. A clip from the funeral is circulating. It… doesn’t flatter anybody. The riders outside look like—well. People are nervous.”

“They were quiet,” I said. “They were a line, not a wall.”

“A camera can’t tell the difference,” she said. “A donor asked if you might make a brief statement. Something like ‘Our family appreciates everyone’s respect during this time and supports safe, orderly gatherings in appropriate spaces.’ Avoid words like ‘ride’ or ‘group.’ If you can avoid saying ‘brother,’ better.”

“I can’t avoid having one,” I said.

She sighed, professional and practiced. “Nora, I’m trying to prevent your grief from becoming someone else’s talking point.”

Behind her voice, a news anchor bled through—a teaser about a “town debate” tonight at seven. The graphics were red and blue and loud. The story would get a name because stories do when they want to go fast.

“I’ll call you back,” I said, and hung up before I could turn my spine into a press release.

Mom closed the last notebook and set her palm on it like a blessing. “He wanted to tell you,” she said to me. “He kept waiting for the right day to be the one where none of it would hurt you.”

“The right day doesn’t exist,” I said. “Hurt arrives on its own schedule.”

We sat in the soft kitchen light with the smell of coffee pretending to do more than it could. The house hummed—refrigerator, heater, the small hydraulics of a life.

“I told the truth badly once,” Evan said, almost to the window. “Right after the press jam, when rumors were spinning faster than the machinery. I told a city council member your father had signed a thing he didn’t chase. The council member said the town needed a clean story. He asked me if I was willing to be the mess so the story could be clean.”

“And you said yes,” I said, heat in my voice that had nowhere useful to go.

“I said I would not correct anyone who thought I was the reason meetings got tense,” he said. “He took that as yes. He let the rest write itself.”

Mom flinched then, small but unmistakable. “You should have corrected him.”

“I tried,” Evan said. “Then I realized corrections have to stand on ground people are willing to look at.”

Liam touched the edge of the notebook with a reverence he usually saved for complicated gear. “We could show this,” he said. “To the people online. To the person who wrote the letter.”

“The person who wrote the letter knows it already,” I said. “Letters like that are written by people who want everyone else to stop knowing.”

My phone vibrated again, as if it were staffed by a newsroom. A new message from an unknown number:

Saw you at the library. Tonight 7 p.m., Channel 8—community conversation about ‘bikes, safety, and Riverbend.’ We’d value your voice. Short segment. Live.

I held the screen toward the table. “There it is,” I said. “The clean story with makeup.”

Evan’s jaw worked, then eased. “If you go on TV, don’t turn Dad into a headline,” he said. “He was not a headline. He was a man who blinked and tried to make amends with his hands.”

“I’m a lawyer,” I said. “I can say true things without throwing bricks.”

“Say the truest thing you can carry,” Mom said. “And leave room for the rest later.”

I gathered the notebooks and the tin and put them back exactly as we found them, like returning borrowed tools to their outline. The key 14–33 went back on the ring. It felt heavier, like it had absorbed the pages.

On our way out of the den, Liam stopped at the family photos on the wall. He pointed at one I always walk past without seeing—Dad younger, at a picnic table, hands black with grease, smiling into a sun I can almost feel. A smudge on his cheek like a fingerprint from his own work. Evan was in the background, out of focus, laughing at something off-camera. I had taken the photo, I realized. My handwriting on the back said Fourth of July, hotdogs, fireworks. I had not written Happy.

Back in the kitchen, the jacket waited. Mom lifted it and held it out.

“You keep it,” she said to me.

“Evan should,” I said, automatic, because my brother had been the one to carry the weight while I carried the story I liked.

“It fits you in a way it never fit him,” Mom said, and for a dizzy second I saw myself on live TV wearing brown leather that smelled like motor oil and church. I set the jacket gently over my arm without promising anything.

As we opened the back door, the winter light flattened the yard into a photograph. Somewhere down the block a delivery truck honked, impatient and harmless. My phone buzzed again—my boss this time, the message thinner than before. Don’t let them put words in your mouth. Also don’t light a match.

I texted back: I’m not going to burn anything. Then: I won’t let them tidy what shouldn’t be tidy.

On the porch, Evan paused. “If you’re going to that studio,” he said, “don’t go alone.”

“I wasn’t planning to,” I said, meaning the jacket and the notebooks and a memory of chalk arrows and bright cones.

“I mean people,” he said. “Not props.”

“I have a son,” I said.

“Bring a neighbor,” he said, and looked at Mom. “Bring the librarian. Bring Reverend Cole. Let the town see the faces that made the drawers make sense.”

Mom nodded, eyes wet and steady. “And bring a key,” she said. “Set it on the table. Let the cameras see something that shines without needing polish.”

The letter was still on the kitchen table under a salt shaker, the word CLEAN going pale with the grease of our hands.

“Seven o’clock,” I said, and felt the familiar lift of going into a room where people expect you to pretend certainty. “We’ll tell the messy truth.”

On our way to the car, the keys chimed in my pocket. The next tag nudged my fingers like a nudge between ribs.

WHARF.

The river would be cold. The wind would be louder by the water. But some doors only opened if you walked toward them when the air bit your face.

My phone buzzed one more time, a small storm gathering. A link blinked onto the screen—someone had spliced the funeral into something it wasn’t, the crop cruel, the caption worse. The comments bloomed like weeds.

I clicked the screen dark.

At seven, I would sit under lights and say something that might not change minds but would make it harder to pretend we didn’t know better.

Between now and then, we had a door by the water to open.

Part 6- WHARF: Lights Checked, Arrived

The tag that said WHARF was thin and bent, like it had been worried between two fingers for years. It clicked against the others in my pocket as we walked from the car toward the river.

Riverbend’s wharf isn’t much—two weathered docks, a walkway of old planks that remember every footstep, a line of lampposts that glow more out of habit than power. The water moved the way it always does here, sure of itself, carrying someone else’s story past our town without asking permission.

The lock we needed was on a shipping container tucked beside a bait shop that survived on coffee and opinions. A painted sign on its door asked politely: RETURN WHAT YOU BORROW. ADD WHAT YOU WISH SOMEONE HAD LEFT FOR YOU. The letters had been traced and retraced, the kind of care you give to a sentence you want to last.

The key turned. The metal rolled back.

Inside, order had been made out of mismatched generosity. On the left: life vests in a range of sizes, rolled and stacked like towels. Next to them, reflective ankle bands coiled like little moons. A bin of hand warmers. A bucket of rain ponchos still in crinkle-wrapped stacks. A dozen battery lanterns charged and ready. On the right: milk crates labeled in tidy print—BELLS, PUMPS, PATCH KITS, LIGHTS. Another crate said STROLLER COVERS, and for a second I saw a mom I didn’t know pushing through a hard winter with a dry sleeping baby and felt a tenderness I could not have manufactured on purpose.

A clipboard hung at eye level. The top sheet read WALK HOME LIST—RIVER PATH. Columns: Name, Start, End, Lights Checked, Arrived. The handwriting was a chorus. Some lines carried initials I’d come to recognize. E.H. more than I wanted to admit. R.H. when I didn’t expect it. M.P. and D.G. and a dozen other small sets of letters that felt like neighbors standing up.

Evan lifted a lantern and clicked it. The light came steady and soft, the kind that fills a shadow without making a speech about it. “In winter,” he said, “the path can feel endless. Lights stop folk from feeling invisible. Bells tell joggers you’re behind them before everyone startles. It’s not complicated. It’s just… attention.”

“Attention is complicated,” I said, hearing how my job had taught me to weaponize sight and how this room had taught my family to lend it.

Liam ran a finger down the columns, stopping at a line from last year. His name—LIAM—printed in careful block letters I recognized because I had helped him practice them. Start 5:45 p.m. End 6:10 p.m. Lights Checked YES. Arrived YES. Initials: E.H. A little star drawn in the corner.

“You walked home with him,” I said, and heard the wobble I didn’t want to show.

“It was dark early,” Liam said. “We checked the lamps. The one near the willows flickers. We left a note.”

He pointed to a sandwich bag pinned to cork under the clipboard—REQUESTS FOR CITY. Inside were slips of paper: “Lamp #12 flickers,” “Bench near park has a loose board,” “Trash can lid missing,” each signed with initials. On the back of one request, someone had scrawled: THANK YOU. FIXED 11/04.

Mom set Dad’s jacket on a shelf and touched the life vests like they might answer back. “We came early some Saturdays,” she said. “Handed out bells and bands, refilled the hand warmers, made a pot of coffee in the bait shop.” She didn’t look at me when she added, “Your father came when he could.”

The words hit the air and held. I watched them settle into the room like dust you can only see when light finds it.

There was a shoe box on a higher shelf. It was lighter than it looked. Inside were notes written on split index cards: Thanks for the stroller cover. The rain didn’t get him this time. — M. // Can we leave two bells? One for me, one for the kid behind me who doesn’t know he needs it. — A. // Found glove. Left it here. — J. A Polaroid lay at the bottom. The river path at dusk, lanterns making small halos, cones arranged in a gentle slalom in an empty lot nearby. In the corner, a figure in a brown jacket had his palms open mid-explanation. My father always taught with his hands.

Evan found a small tin labeled MATCHES but inside were keys. Five. Plain brass, tags blank, edges smooth from pockets. “People borrowed and forgot to write their names,” he said. “Or wrote and the ink faded.”

Behind us came the creak of old boards and the rumble of a laugh I’d recognize in a blizzard. “You beat me to it,” Reverend Cole said, stepping in, cheeks pinked by the river wind. Ms. Parker was with him, a scarf looped to within an inch of its knitting life.

“I brought the thing I’m good at,” she said, raising a paper bag that betrayed the corner of a cinnamon roll. “And the sign-out book. It got wet last week. I copied what I could save.” She set the bag on a crate and pulled out a new ledger, crisp and squared, the first line already written in her neat hand: Today—Refill—Lanterns 8/8, Bells 12/12, Bands 27/30.

“Tonight at six, the church hall,” the Reverend said, turning to me as if continuing a conversation I hadn’t heard. “We’re holding an hour where people can tell a small truth that doesn’t need a microphone. No photos. Anyone talks longer than two minutes, I cough and they forgive me.”

“Two hours before the TV thing,” Ms. Parker added. “Consider it a warm-up, except it counts more.”

I looked at the clipboard again, at the small Yes that ends a line. “You think people will come?”

“They already do,” Reverend Cole said. “They’ve been showing up for years. They just thought it was to borrow a vest.”

We worked without talking much. Liam tested lanterns. Evan checked pumps. Mom sorted bands by pairs. I took Ms. Parker’s new ledger and wrote headlines for what I thought mattered—Inventory, Notes, Borrowed—then crossed out Borrowed and wrote Shared. It felt less like paperwork and more like a promise not to let this room become a rumor.

At six, the church hall smelled like soup and folding chairs. A hand-lettered rule taped to the door read: LISTEN FIRST. Then a smaller rule under it: NO CAMERAS. Ms. Parker sat at a table with a pot of coffee and a basket of those little creamer cups that never expire. Reverend Cole stood at the front with a bell he promised never to ring unless truly necessary.

People came because they always do when the invitation is simple and the door isn’t heavy. Mrs. Whitmore—our widowed neighbor with a garden that outgrows her every summer—took the mic first and spoke without looking at it. “Somebody kept my porch light going,” she said. “Not metaphorically. The switch broke. I found a note and a new switch in a bag with a receipt. I don’t need to know who. I need to say thanks.”

Mr. Delgado from the machine shop kept it to his two minutes and made all of them count. “Saturday mornings, the cones show up and my boys stop running in the street. They ride slow circles in chalk lines and go home tired in the good way. Not everything needs a grant name. Some things just need chalk.”

A nurse from the clinic, still in scrubs, lifted her eyes once, then again. “I don’t know who left the envelopes,” she said. “The handwriting changed. The amount changed. The timing didn’t. It made a difference between a parent showing up and a parent staying home.” She put the mic down like it could break if handled wrong.

A teenager I didn’t know stood and gestured at his ankle. “They gave me these.” He wiggled a reflective band. “I didn’t get hit that winter, which I think was the point.”

Evan refused the mic when it was offered, lifting his palms and shaking his head. He stood at the back and leaned against the wall the way a person does when they’re trying to occupy the least amount of vertical space possible. When our eyes met, he lifted his chin an inch. He was proud of the room and embarrassed by the part where anyone might accuse it of belonging to him.

I took a turn because I had to teach my mouth new work. “My name is Nora,” I said, which felt like a confession. “I am guilty of liking tidy stories. I don’t know how to fix machines. I do know how to fix paperwork.” A few chuckles, sympathetic, the kind you give a recovering something. “If we have to build a boring scaffold to keep this alive, I can bring nails.”

I didn’t say my father’s name. I didn’t say Evan’s. I let the room stay bigger than our house.

In the back, by the bulletin board, a man in a baseball cap took notes without looking up. The same cap had been at the shop that morning, or maybe caps all over town look like that when you’re suspicious. When he caught me seeing him, he smiled in a way that meant nothing and everything and folded his paper too neatly.

At ten to seven, Reverend Cole closed us with a prayer that was not about sides and very much about hands. Ms. Parker tucked tidy piles of cups into a bag the way only librarians know how. People carried their listening back out into the cold like it might steam if they didn’t hold it close.

My phone buzzed. Channel 8: Quick update on format: panel discussion. You, a city rep, and a spokesperson from the Business Alliance. Also opening with the viral clip. See you soon!

A second message stacked on the first: Caller segment added. “Community concerns.” Live.

“Panel,” I said aloud, as if naming it would make it less likely to bite. “And a clip.”

“Bring the truth that breathes,” Reverend Cole said. “Not the kind that shouts.”

“And bring a face the town trusts,” Ms. Parker said, picking up her scarf.

“Two,” I said, looking at both of them. “If you’ll come.”

They nodded like they’d already put on coats in their minds. Mom touched my elbow and slid the jacket over my arm until it sat there as if it had been made with me in mind. I smelled leather and church and maybe coffee and coal—memory notes only a town like ours mixes.

“Keys?” she asked.

I held up the ring. It chimed. The WHARF tag nudged my knuckle like it wanted to be noticed one more time.

As we stepped into the parking lot, a wind came off the river with more intent than the last one. I clicked the car unlocked and glanced at the rearview mirror. Stuck beneath the wiper, neat as a parking ticket, was another envelope.

No stamp. No return address. The same block letters trying not to belong to anyone.

I waited until everyone else was buckled and the heater was thinking about beginning. Then I slid a finger under the flap and read.

IF YOU GO ON AIR, KEEP IT CLEAN. PEOPLE ARE TIRED. DON’T MAKE THIS UGLY.

I lifted the note so everyone could see it. No one said anything. The car filled with the sound of breath, of zippers, of a scarf uncoiling.

“Ugly isn’t the same as complicated,” I said, and the sentence surprised me by sounding like something my father would have written when no one was looking.

We pulled out into the thin downtown and headed toward the studio lights. Outside my window, a lamppost near the river path flickered, thought about it, and came steady.