Part 7- On Air: The Hidden Seam (BRIDGE)

Channel 8 looked smaller in person, like a dollhouse version of the room I’d been imagining all day. The lights were close to your face, the chairs were closer to each other, and the makeup person said “chin up” in a way that made you want to apologize for having a chin.

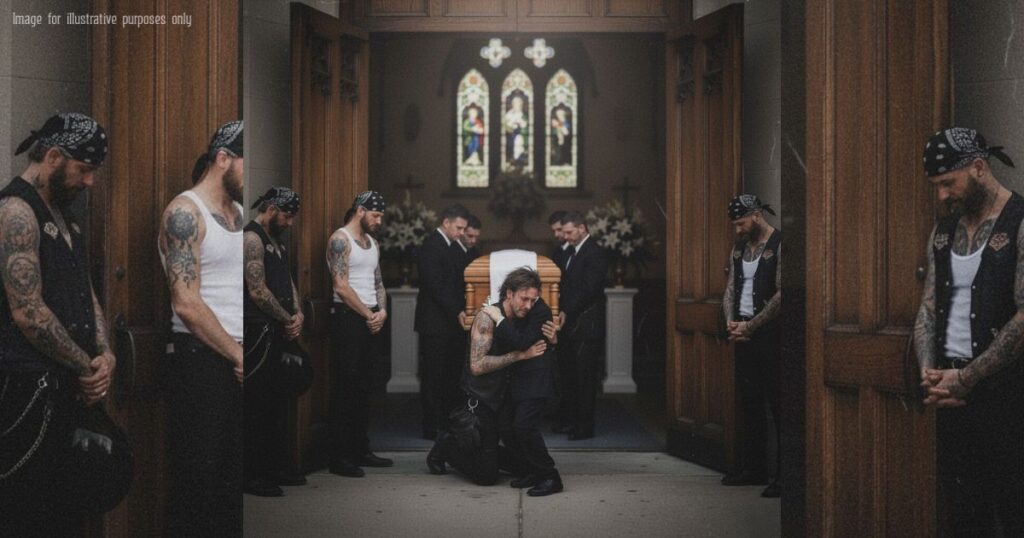

“Thirty seconds,” the floor manager mouthed, swiveling his finger in the air. A monitor on the far wall showed the opening graphic: COMMUNITY CONVERSATION: BIKES, SAFETY & RIVERBEND. Underneath it: a thumbnail of the viral clip from the funeral, cropped to make a quiet line of riders look like a barricade.

To my left sat a city representative in a navy suit with a lapel pin that said everything without saying anything. To my right, the spokesperson for the Business Alliance—blonde bob, perfect posture, the kind of smile that can be polite and sharp at the same time. Reverend Cole and Ms. Parker had squeezed into the front row of the tiny audience, two faces I could trust when the cameras turned the room into a mirror.

“Ten,” the floor manager counted with his fingers. “Five… four…” He pointed to the host, who looked exactly like a host: calm eyes, tidy hair, the news voice people turn up for and then quote to each other in kitchens.

“Good evening,” she began. “We start tonight with a clip many of you have seen.” The screen behind us went full-frame: the church doors, the casket, the line of engines along the curb, the camera tilted just enough to make space look like crowding. No sound, only the hush turned into suspicion.

The host turned back. “With us: Nora Hale, community member and attorney; Darren Tillman from the city; and Marla Kent from the Business Alliance. Ms. Hale, was this respectful? Was it safe?”

I felt the jacket on my shoulders—a brown weight that had outlived two job titles and one idea of who my father was. I kept my voice steady. “It was respectful,” I said. “It was quiet. Helmets off, engines off, a line with space between. If anyone felt uneasy, that matters. Perception is part of safety. So is context.”

“Context being?” the host prompted.

I set a single brass key on the glass table where the camera could see it catch light. “We’ve been opening rooms around Riverbend,” I said, and I told the story without names: a storage unit with loaner helmets, a library cabinet where a neighbor can be a neighbor, a city garage where cones teach patience in chalk, a wharf container with bands and bells so people feel seen in winter dark. “We can make it official—permits, headcounts, inspections—without erasing the drawer that someone opens because they can’t carry their pride through a door marked ‘Applicants.’”

The city rep nodded. “We’re committed to safety,” he said. “We’ll work with any group that wants to operate within the guidelines.”

Marla folded her hands. “Businesses support good deeds,” she said. “But ‘good’ can’t become chaos. Downtown merchants are uneasy. Crowds form, and customers stay away. Liability is not a feeling; it’s a bill.”

There it was: the word from the letter, polished for TV. Keep it clean.

The host lifted a tablet. “We’re opening the phone lines. Please keep comments brief.” The first caller wanted rules, fines, less noise in general. The second caller was a mom who said the band on her child’s ankle glowed like a promise and she slept better because of it. Then a third voice threaded the middle—older, a little gravel, the sound of someone who used to shout over machinery and then stopped.

“My name’s Cal Benton,” he said. “Press line two, back when there was a press line. I’m calling because I heard a key hit a table.”

I went still. Out of the corner of my eye, Evan wasn’t there—on purpose—but I felt him anyway, a gravity on the edge of the room.

“Mr. Benton,” the host said smoothly. “Your comment or question?”

“Comment,” he said. “And a correction. The story you’re all trying to keep clean—some of us have the smudges you’re missing. Your father, Ms. Hale, wrote conditions on a run order that never made it to the final print. He penciled a note—‘Only if inspection confirms safety.’ Those attachments went missing. Someone told me to let it be missing. I made a copy.”

My heart did something I could have used a first-aid kit for. “Where is it?” I asked before my brain could smooth my voice.

“In a blue envelope,” he said. “I slipped it to a librarian who has better sense than me. And there’s something else. Your dad asked me, years back, to stitch a pocket into his jacket. Hidden. Left side, under the seam. Said a hard day might come when his daughter needed a key and he wouldn’t be there to hand it to her.”

I felt the room tilt. The jacket warmed against my skin like it had a secret it was finally allowed to share.

The host blinked, mid-script, then recovered. “Thank you for your call,” she said, and her voice did a strange thing—respect sneaking in around professionalism. “Ms. Hale, any response?”

“Yes,” I said, because a thousand words were too many and one was what I had. “After this, I’m going to check the seam.”

Marla smiled the way you do when you think you’re winning on points. “Again, businesses support—”

“Marla,” the host cut in gently, “we’ll give you the last word after this break.” She turned to camera one. “When we return, our panel on how to move forward safely—without losing sight of what neighbors already do for one another.” The red light blinked off. “We’re clear,” the floor manager called, and the room broke into the tiny chaos of commercials—water bottles, whispers, a makeup brush floating past like a fairy.

Ms. Parker moved fast and small, like a lint roller with purpose. She fished in her tote, pulled out a blue envelope with the library’s return stamp on one corner, and slid it across the front row to me. The flap had been sliced open and then tucked back. Inside: a copied page with my father’s penciled note at the bottom: Only if inspection confirms safety. Underlined once, hard.

I imagined the copy made, the original filed, the piece that mattered going absent, a story shaved until it looked tidy in daylight. “He tried,” I said, to no one and everyone.

Reverend Cole leaned forward. “Try louder now,” he said. “You have a microphone.”

We went back on. The host did what hosts do—framed, balanced, made room. I kept my answers boring on purpose. “Yes to permits. Yes to headcounts. Yes to inspections. Yes to a code of conduct. And yes to leaving a corner for the drawer that lets someone try on pride that still fits.” Darren nodded—grateful to say yes to things that could be printed on forms. Marla said “liability” twice more and “perception” three times, and I didn’t flinch when she did.

Before the credits, the host surprised me. “Ms. Hale,” she said, “one sentence for people watching who think they are tired.”

I looked straight at the camera because I wanted this to land someplace a letter couldn’t reach. “Ugly isn’t the same as complicated,” I said. “If you’re tired, help us carry the part that’s heavy.”

The red light went dark. Applause bristled and died. The host squeezed my hand with a pressure that said she knew what a sentence costs.

In the hallway, a man with a baseball cap waited, not hiding, not hurrying. He took off the cap like he was stepping into church. “Cal,” he said, offering his hand. His palm was scarred the way palms get when they’ve chosen wrenches over keyboards. “Your dad asked me to keep that copy where it wouldn’t get lonely.” He nodded at the jacket. “Seam, left side. Tiny pocket. You’ll feel the knot.”

In a corner, Marla shook hands with a donor I recognized from the gala circuit. I don’t have anything against gala circuits; I have something against sentences that sound like my letter when they come out of living mouths.

“I appreciate you appearing,” she said smoothly as she stepped over. Up close, her perfume smelled like decisions. “For everyone’s sake, let this be the last round. The town needs to move on. It’s… tired.” She said it like a diagnosis. Or a script.

“People said that after the plant closed,” I said. “Then they got up and went to work the next morning anyway.”

Her smile flattened. “There are ways to help that don’t involve… optics that worry insurance.”

“Like envelopes without names?” I asked.

She didn’t answer. She didn’t have to. She already had.

Out in the cold night behind the studio, the parking lot lights hummed. The wind riffled the edge of a poster for next week’s news special. Ms. Parker stood on tiptoe like a mother with a scarf and found the seam on my jacket with her fingertips. “Here,” she said, and I felt the tiniest ridge. A knot. The kind Dad had used when he tied fishing line, firm and small and meant to keep.

I slid my thumb under the stitch and felt it give. Not a rip. A release. The lining opened just enough for two fingers. Something small and solid rested against the leather, warm from being on my shoulder.

I pulled out a key. Not brass—steel, thin, a little pitted. The tag was a sliver of aluminum, stamped, not by the tidy set that labeled RIVER and LIB, but by a hand with a nail and a hammer. BRIDGE.

Reverend Cole sucked in a breath the way a person does in a sanctuary when stained glass catches just right. “Of course,” he said softly. “The footbridge.”

Cal nodded once, like a man watching a plan he promised to keep unfolding on time. “He liked to go there early,” he said. “Before the town woke up. Said water told the truth before anyone else had the chance to.”

I curled the key into my palm. It was colder than the night and warmer than everything I didn’t know how to hold. Liam’s hand found my sleeve. “We going now?” he asked, not out of impatience. Out of something that felt like belonging.

“Tomorrow,” I said, and kept my voice from shaking by making it a plan. “Dawn.”

Ms. Parker squeezed my arm. “I’ll bring coffee.”

“Bring bells,” Reverend Cole said. “Even the river likes to hear you coming.”

As we walked toward our cars, a man in a puffer jacket—the city inspector from the garage—stepped out of the shadow of a lamppost. He looked at the key in my hand, then at my face, and—God bless clipboards—did not ask what it opened. “Reinspection moved up,” he said. “I pushed. Morning after next.”

“Thank you,” I said, surprised by the way the town kept showing up dressed as individuals.

He shrugged. “Tired isn’t an excuse,” he said. “It’s a condition. Conditions change.”

When we turned the corner, the studio door closed behind us with a soft thud that sounded like a book being returned. In my pocket, the ring of keys chimed. The new one didn’t. It didn’t have to. It had already rung.

At home, in the quiet kitchen, I set the steel tag next to the other keys and watched how different it looked—rough, urgent, not interested in being pretty. Mom touched it with one finger and didn’t take her hand away.

“What do we expect to find?” Liam asked.

“Not clean,” I said. “But true.”

Outside, the town settled into the part of night when people decide what kind of morning they want. I stood with my palm over BRIDGE and let the weight of it argue with everything that had told me to keep my hands clean.

Tomorrow at dawn, we would go where water kept records without filing them. And if the story we brought back didn’t fit in anyone’s mailbox, we would stop trying to send it there.

Part 8- BRIDGE: A Minute of Quiet, A Line of Washers

We met the river before the sun did.

Frost made the footbridge rails look sugared. Our breath hung and then went where breath goes. Ms. Parker’s coffee steamed like good intentions. Reverend Cole shuffled in with a paper bag of bells and the kind of smile that holds you steady without making a big deal of it. Cal Benton leaned on the lamppost and nodded once, already part of the weather.

The key lay cold in my palm. Steel, thin, stamped BRIDGE by a hand that used nails, not machines. Evan knelt by the center post where the rail met the support. He ran his fingers along the underside like a mechanic listening for a rattle. “Here,” he said, tapping a small weatherproof box bolted cleanly to the metal. It was painted the same dull gray as the rail. It had been here all along, the way some truths are.

The lock accepted the key and turned with a click that sounded like a promise being kept late instead of never.

Inside: a folded page in a plastic sleeve, a small tin of washers threaded with twine, and a laminated card the size of a library card. On the card, in Dad’s tidy print: IF YOU BORROW, RETURN. IF YOU CAN, LEAVE ONE. IF YOU’RE NEW, WELCOME.

I slid the sleeve out. The page was lined paper, the kind from a spiral notebook, edges fluffed where it had been torn slow. The date at the top was five years old. The handwriting was my father’s steady foreman script.

“Read it,” Mom said, her voice a little breathless, like she’d jogged a short distance in a long memory.

I read.

“Nora—

If you’re here, the day I whispered about arrived. I could not be two men in two rooms. I tried to be useful where quiet counts and tidy where noise insists. I owe apologies you’ll have me deliver in public if you ask.

The three of us made a promise at this rail. Your mother, your brother, me. If the town gets loud and scared, we bring them to the water. Not for speeches. For a minute of standing still in the same direction.

If you carry this now, make it official where it protects people, and leave a drawer where dignity fits. Let Evan teach what he knows. Let me be wrong where I was wrong and right where I was right without trying to balance that ledger like it can ever come out even.

Hang a washer for every time a key made a lock kinder.

—Dad”

Evan took in one breath that went deeper than the rest and let it out slow. He didn’t wipe his eyes. He also didn’t blink until it passed.

“What promise?” I asked, looking at the rail, looking at their hands as if I could find the shape of an old vow in their fingers.

Mom touched the metal with her palm. “We promised not to hide in the clean story if the true one needed us,” she said. “We promised to make space for neighbors to show up for each other without putting them in a brochure.”

Cal cleared his throat. “He made me test the lock twice,” he said, pointing at the box. “Said if I could open it with cold hands, anyone could.”

I thumbed the tin. Inside, the washers were ordinary—hardware store, bag-of-fifty kind. Each had a loop of twine tied through it. I threaded one on my finger and felt its simple weight. It wasn’t a medal. It wasn’t worth anything alone. Together, they could hang like rain on a roof edge and make a sound that says, We’re here.

“Let’s do what he asked,” I said. “No speeches.”

We texted as the sky traded gray for blue. Ms. Parker sent six messages that read like invitations and exactly none that read like orders. Reverend Cole posted a note on the church door: ONE QUIET MINUTE—FOOTBRIDGE—SUN UP. He brought the bell and didn’t ring it.

People came the way they always come when you ask for something simple. A night-shift nurse with her bag still over her shoulder. A man in a reflective vest who parked his leaf blower and walked. Mrs. Whitmore with her garden gloves in her pocket just because. A group of riders rolled in, cut engines a block away, and walked the last stretch with helmets in their hands so the morning would stay a morning.

We lined the bridge. Not packed. A line with space between. The river moved the way a crowd used to move shift-change mornings, steady and without commentary.

I set my timer for sixty seconds and didn’t say a word. We stood and did nothing together. It felt like the opposite of television and exactly like a town.

The minute stretched in that good way time does when it is doing a job. I heard small things—bolts settling in cold metal, a child’s shoe tap, the click of a lantern someone checked twice just because. A goose made a low throat noise and then thought better of it.

When my timer hummed, no one moved at first. Then Mom reached into the tin and looped a washer over a screw head on the rail. It chimed when the wind nudged it. Evan hung one. Liam hung one. Ms. Parker hung one and patted it like a pet on the way past. People followed, not in a line, just in the rhythm people find when they’ve decided to match each other without being told.

A boy I didn’t know stood on his tiptoes and handed his washer to his taller sister to hang for him. A man with hands like mine—courtroom hands, not toolbox hands—fumbled and laughed and got it right on the second try. The riders draped keys on the rail, old ones they’d found in drawers, anonymous and bright, a jangly choir.

No one took a selfie. It would have been fine if they had. It was finer that they didn’t.

When the tin was almost empty, Cal lifted a single washer, looked at the hole, and then slid it into his pocket. “For the press line,” he said, not loud and not to anyone in particular. “For what we couldn’t fix with a wrench.”

I set the laminated card on the rail where the morning could see it. IF YOU BORROW, RETURN. IF YOU CAN, LEAVE ONE. IF YOU’RE NEW, WELCOME. It looked like a rule and felt like an invitation.

We were packing the box—paper back in sleeve, washers back in tin, key turned—when a planning notice caught the corner of my eye. Someone had taped it to the lamppost by the bridge stairs. Public Hearing: Proposed Riverbend Riverwalk Revitalization—Phase 2. Agenda items included upgrades I liked (benches repaired, lamps replaced) and a line that hit my stomach like a cold cup dropped: Reassessment of municipal garage on Maple for alternative use (request for demolition and redevelopment).

I took a photo because even when you don’t want to, documentation matters. The date of the hearing was two nights from now. The time was 7 p.m. The location was City Hall. Agenda Item 7. Speakers limited to two minutes.

“Of course,” I said. It wasn’t a complaint. It was a translation.

Evan read over my shoulder and didn’t swear. “Alternative use,” he said. “Like a bakery needs flour for an alternative use.”

“Like a grant needs a ribbon cutting,” Ms. Parker said quietly.

Reverend Cole rubbed his palms together, not for warmth. “Two minutes can hold an ocean if you pour it right.”

We started back toward the parking lot. On the bulletin board near the bait shop, a flier had bloomed since yesterday. RIVERBEND BUSINESS ALLIANCE—KEEP DOWNTOWN WELCOMING. Bold text beneath: SUPPORT SAFE, CLEAN SPACES. The photo showed a sunlit sidewalk café. The fine print mentioned “reducing unregulated gatherings.” It didn’t show cones in chalk lines or a child’s ankle band bright in the dark.

“I’ll meet with them,” I said, surprising myself with the certainty in my voice. “Not to fight. To invite. They want welcome. So do we.”

“Bring a washer,” Cal said. “Hand them something that doesn’t look like a press release.”

My phone buzzed. A message from the city inspector, the one with the puffer jacket and the face of a man who doesn’t enjoy conflict but knows it isn’t optional: Reinspection moved up again—tomorrow dawn. Bring documentation. I’ll bring the checklist. Also: thank you for the minute on the bridge.

I typed back: Thank you for pushing. Then: I’ll bring boring paperwork and a not-boring room.

Liam tugged my sleeve. “Mom,” he said, tilting his head toward the river. A small line of washers we’d just hung chimed together like a wind had decided to become a choir. The sound was thinner than a bell and stronger than silence.

We weren’t done.

We stopped by the library on the way home. Ms. Parker slid the blue envelope copy of Dad’s penciled condition into a sheet protector and labeled the top: ATTACHMENT—NOT FOUND IN FINAL PRINT. She wrote the date. She added: Returned to daylight.

At the counter, a teen with purple hair checked out a stack of paperbacks the color of summer. She glanced at the washers in our pockets and didn’t ask. She’ll know what they mean later, I thought, the way you grow into your town if your town makes room for it.

Back at the house, I set Dad’s bridge letter on the table and made a list that looked like a case file and felt like a recipe.

- Fire extinguisher inspection.

- Headcount plan.

- Saturday lot permit (dust off the old application, add the pilot approval if we can find it).

- First-aid kit inventory.

- Statement for hearing (two minutes; no adjectives we can’t defend).

- Invite: clergy, clinic, shop owners, nurse, Mrs. Whitmore, Mr. Delgado, teen with band on his ankle.

- One washer for the dais.

Mom watched my pen move. “You think better when you give your hands something to do,” she said, and I heard my father telling me the same thing in the garage when I was eight and wanted to be the boss of the screwdriver.

Evan set the BRIDGE key next to the ring on the table. “There’s one more,” he said. He didn’t lift his eyes. He didn’t have to. I felt the nudge before he said it. “PARK.”

The word was simple and full. The chalk lot. The cones. The place where Dad had looked like a neighbor in a leather jacket with his palm on a boy’s shoulder, mid-sentence.

“We’ll go after the inspection,” I said. “We’ll go again and again if we have to.”

Liam slipped a washer onto a piece of twine and tied it to his backpack zipper. It made a small sound when he moved. “So I don’t forget,” he said.

“Forget what?” I asked.

“That a drawer staying open is somebody’s job,” he said. “Might as well be ours.”

That afternoon, as the town decided whether to argue in comment sections or in rooms where eyes meet, a row of quiet keys glittered in pale sun along a bridge rail. They rang when the wind shifted. The sound was not loud. It traveled anyway.

At dusk, my phone lit with a new email: Planning Commission—Agenda Materials Uploaded. I opened the PDF and scrolled until I found a rendering of “Alternative Use: Maple.” The building was turned into “flex space”—the kind that photographs well. The caption said: “Community programming TBD.” Under “TBD,” a handwritten note had been scanned by accident. One word. “Liability.”

I stared at it until the screen timed out.

The bridge letter lay under my hand like a pulse. The washers on the table made a small, accidental pile. The next key on the ring pressed against my palm as if it had been listening to the river and learned persistence.

Tomorrow, before the sun, we would meet a clipboard at the garage door and ask it to recognize a room. And tomorrow night, we would decide what to say in two minutes that could hold a town without making it tidy.