This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta

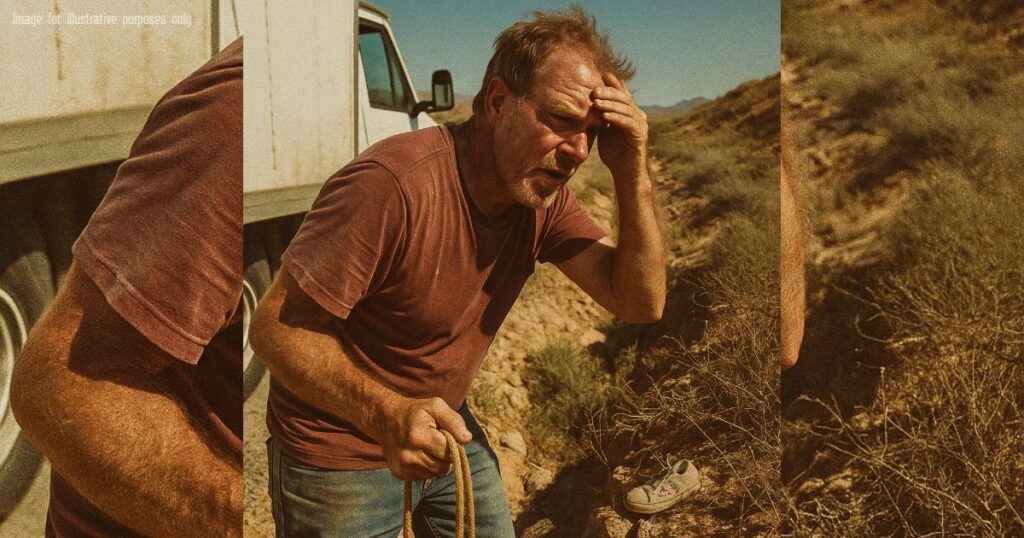

The shoe shouldn’t have been there. Wedged in the desert brush, miles from any town, it was a silent question. While hundreds of others drove by, this one man felt compelled to stop and find the answer.

A single light-up sneaker, blink dead, wedged in a thorny crown of desert brush ten feet down a rock cut off Highway 191—too small to belong to any of the men who roared past in lifted trucks, too bright once, once upon a time, for the dirt-softened world where it had landed. The wind had pushed sand over its toe like a blanket someone forgot to tuck in. Nobody stopped. Not the tourists hauling boats. Not the convoy of search volunteers already late to meet at Mile Marker 73. Not the state trooper who’d slowed, looked, and looked away.

But Marcus Johnson did.

They called him Red once—before prison and after it—because the sun had burned the color into his scalp when he worked roofing, back in the life that came before losing almost everything. Fifty-eight, hands cracked, freight rattle in his chest from twenty years of diesel air, sleeping most nights in the cab of his dented white box truck behind a tire shop in Holbrook. No one expected the man eating a gas station burrito at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday to become anything more than a minor inconvenience in the rearview mirror.

He eased onto the shoulder anyway, blinkers ticking like a metronome nobody else could hear.

He didn’t know about the news alerts other phones were buzzing with. Didn’t have a phone that pushed headlines; his was pay-as-you-go and mostly off. He didn’t know an eight-year-old boy named Caleb and his parents had been missing five days since a family drive went wrong in a thunderstorm. Didn’t know a hundred people had lined up to walk gridded fields, that drones had mapped canyons like veins on a marble hand, that the world had already started to move on.

He knew about shoes, though.

He knew how you carry a kid on your hip and they kick one loose because they’re having more fun than gravity. He knew the hollow feeling that opens in your chest when a little body is no longer in the house and the night is too quiet and you realize the last words you said the day you left were not the ones you want remembered. He knew what it was to wish for a second chance and wonder how many miles away it had wandered while you weren’t looking.

Red killed the engine and rolled the window down. The heat hit like someone had opened a dryer mid-cycle. He listened anyway. Heat has a way of making silence sound like something breathing.

“Hello?” His voice startled the sneaker birds out of the brush. They rose, resettled. “Anybody down there?”

Only wind and the faraway hiss of tire on road answered back. He unclipped the bungee that held the truck’s side door shut, rummaged in the dark for rope and a faded red tow strap he wasn’t sure he could trust. He wasn’t a climber; he was a man who’d learned to knot things you didn’t want falling off at seventy miles an hour. He wrapped the strap around a road sign post and tested it twice with his weight. It groaned and held.

“Stupid, Red,” he muttered, the old nickname slipping out of habit rather than pride. “Stupid or what.”

But the sneaker—child small, cartoon stars now dust—wouldn’t let his feet move back to the cab. He braced his boots and backed down the rock face, sideways, rope burning through his palms.

Halfway down he saw the scrape marks. Fresh, desperate, only a few rains old, which in this part of Arizona could mean three months or three minutes. He lowered further and smelled it then—the sour, coppery air of something broken open.

The ravine wasn’t deep, but it was mean: a tumble of boulders like a set of bad teeth, scrub clawing where a trickle of water sometimes ran. At the bottom lay a silver crossover SUV on its roof, windows gone to diamond powder, tires still sighing out heat. A thin smear of oil blacked the sand. One door hung open like a mouth that didn’t know what else to do.

“Hello!” Red shouted, and ducked his head to listen again, like you do when someone tells you a secret and you need them to tell it twice.

A sound came. Very soft. Like the smallest cough in a church pew.

He moved without thinking then, sliding down the last six feet and banging his knee hard enough to make stars, which only meant the world was still working. He crawled to the open door and peered in.

“Hey,” he said, because “hey” is what you say to a skittish dog and a scared child and a mirror when you don’t recognize yourself. “Hey there, buddy.”

A boy blinked back at him from the narrow pocket where the roof had crushed down to meet the center console, tucked into space the size of a suitcase. Dirt made freckles across his cheeks where there were none. His lips were cracked white at the edges. He wore a T-shirt with a dinosaur that had been roaring happily an entire lifetime ago.

“Water,” the boy whispered.

“Yeah,” Red breathed, voice shaking like it had cold though the day was already making iron warm. “Yeah, hang on.”

His mind ran inventories faster than his hands could. Water jug behind the driver’s seat—two inches left. Clean T-shirt—one, size XL, rolled to a pillow. First-aid kit—expired, but tape is tape. He found the jug and angled it to the boy’s mouth. “Only a sip,” he said, gentle. “Just a little. That’s it.”

“Mom?” The boy’s eyes skittered past Red, hunting the car’s inside like something might be hiding there if only he looked hard enough. “Dad?”

Red had been out of practice with prayers since he was nineteen and a judge told him to sit down and listen, but his heart said one anyway. He looked to where the boy was looking and saw the shape behind the front seats. He reached across the console, fingers trembling, and touched a wrist he knew would be cold before his hands got there.

“I’m sorry,” he said, to the boy, to the shape, to the hungry heat.

The boy closed his eyes like doors shutting. “Dad fell asleep,” he whispered. “It was raining and Mom said she was fine to drive but he said he could handle it and the road went away.”

“You’re okay now,” Red said, and believed the half-truth as much as he could. “You’re with me.”

He checked the space. The kid’s legs were pinned where the dashboard had folded. His left ankle was the wrong shape. He didn’t see blood, which scared him as much as it comforted him. He could hear a drip somewhere, and hoped like anything it was water, not gas.

He slid his arms into the crevice, felt the boy’s narrow back and the tiny bird-bones of shoulder blades. “What’s your name, little man?”

“Caleb,” the boy said, a breath more than a word.

“I’m Marcus,” Red said, because you don’t bring an old name into a new promise. “We’re getting you out. You and me.”

The metal fought him. He set his shoulder and pushed, and his body made a sound he’d last heard on a prison yard when a man lifted more than he should to prove something the world never gave him a chance to prove. The dash rose a half inch. Another. He slid one arm under Caleb and heaved, the boy slipping free like a letter someone forgot to open. Red backed out, carrying the small weight that felt heavier than a lifetime, and then they were outside the car and the sun was on them both.

Caleb coughed and gulped dust and coughed again. He clutched Red’s T-shirt and wouldn’t let go.

“You a policeman?” he asked, voice raw.

“No, buddy.” Red eased them both into the shadow of a mesquite. “I’m just a driver who finally did one thing right.”

He checked the ankle. He knew better than to be a doctor, but he also knew that sometimes you didn’t get the luxury of waiting for the perfect plan. He splinted it with cardboard and duct tape, the two great tools of every American truck and dream. He had no service on his phone when he held it up. The road was close enough to hear but far enough to pretend it wasn’t there.

“How long were you here?” he asked.

Caleb stared at the sky the way a kid studies a ceiling when he’s trying to count the cracks. “A lot,” he said. “The light turned off yesterday.”

“What light?”

He pointed at the sneaker. “The shoe light. It made Mom laugh when it blinked. Then it didn’t anymore.”

Red felt his throat tighten. “Okay,” he said, and because action was the only cure he’d ever found for that feeling, he got to his feet. “We’re going up.”

The climb was meaner going up. The rope dug into his palms where his calluses had peeled. Caleb wrapped his arms around Red’s neck and breathed small hot breaths in his ear. Red talked to him, talked to the rocks, talked to the road. Told them all about the way a carburetor smells sweet when you’ve got it tuned right, about the good weight of a kid asleep on your chest, about second chances like coins in a jar you never thought you’d get to empty.

They left the ravine one inch at a time until they were back in the hot rattle of the shoulder and Red’s truck looked like a motel he’d built himself. He laid Caleb on the passenger seat and buckled him in and tucked a rolled-up hoodie under his splinted ankle.

“You ever ride in a truck with no air-conditioning?” Red asked, half grin, half apology.

Caleb shook his head, the ghost of a smile tugging. “Mom said we’d do it when we go see the Grand Canyon so we know what it was like when she was little.”

Red swallowed. “Well, we’re getting you to people who know what to do. You hold on.”

He started the engine, said a quiet word to the old transmission, and pulled onto the highway. He honked once, short, at the empty space in the mirror where the ravine was now just a cut in the earth that would never tell its stories to anyone who wasn’t willing to listen.

At Mile 74 the bars on his phone blinked awake. He hit 911 and spoke the address off a green sign like a catechism. The operator’s voice was bright and professional, and when he said the word “child” it changed to something softer, almost a whisper, as if she could see their faces.

They met the ambulance at a crossroads with a burnt-out church and three mailbox posts leaning like a jury. EMTs moved the way good mechanics do—fast, precise, calm enough to make the rest of the world slow down and take a breath. They lifted Caleb and worked and asked questions and Red gave answers and at some point someone unclenched his fingers from the steering wheel. He stood there in the stained T-shirt a kid had clung to and realized he was shaking.

“You with him?” an EMT asked, already knowing the answer.

“I am now,” Red said.

They took Caleb to a hospital in Holbrook. Red followed in his truck and kept losing the ambulance and then finding it again at stoplights, like life letting him practice the rhythm of holding on and letting go. In the ER, a social worker with a badge and a kind face wrote his name down and asked him to sit while a doctor with a voice like a good teacher explained words that translated mostly to this: fracture but clean, dehydration but fixable, scrapes and bruises, and a resilient heart you could hear if you leaned close.

The news found them by dinner. Someone had heard the scanner call. Then someone else had posted a photo of a white box truck on the shoulder with a rope dangling down the rocks, and after that the internet did what it does—turned a mile of empty road into a stage.

“Are you the driver?” a reporter asked, and Red looked around to see who she could possibly be talking to.

He answered as few questions as he could and as many as he needed to. He did not say “ex-con,” though someone would write it anyway. He did not say “father,” though the word kept lighting up the old rooms inside him. He said “my name is Marcus Johnson,” and when they asked where he lived he said “in my truck,” and when they asked what he wanted he said “the kid to be okay.”

He slept in a chair in the waiting room because the security guard didn’t make him move. He woke to a paper cup of coffee someone had left and the slow pink of morning pushing at a window even the janitor hadn’t bothered to clean.

“Mr. Johnson?” a woman said, and he looked up into eyes that had cried more in five days than his had in five years. She introduced herself as Rachel—Caleb’s aunt. She hugged him the way family does when they recognize something they didn’t expect to recognize. “He says you found him,” she whispered. “He says you kept saying ‘we’ like he wasn’t alone.”

Red nodded, because there is a dignity to not filling a moment with words just because you’re afraid of the quiet.

“Can I… can you come with me to see him?” she asked.

“Does he want that?”

She smiled through the kind of tired that makes you brave. “He wouldn’t let the nurse wash your shirt because it smells like the air outside.”

Caleb was smaller sitting up in the hospital bed than he had felt in Red’s arms. He had a cast and a teddy bear someone had found in a donation bin and a carton of chocolate milk with a straw crimped funny like it was thinking about the next move. He lit up when Red walked in, and the light caused something in Red’s chest to click into a setting he hadn’t used in a long time.

“You came back,” Caleb said.

“I said I would,” Red answered.

“Are you a hero?” Caleb asked, not like the TV does it, but like a kid testing the edges of a word.

“No.” Red pulled up a chair that squeaked like it had old ghosts in it. “I’m a driver who decided to stop.”

After that, the days moved like they do when hospitals are involved—slow and then fast and then slow. Reporters asked to film; the aunt declined most of them; one crew caught Red coming out of a vending machine room and someone on the internet wrote a comment that started with “He looks like—” and ended with a word Red had heard on both ends of his life. A sheriff shook his hand and said the word “commendation,” and Red shook his head and said, “Save it for the kid.”

The debate started online like fire does—small and crackling and then taking to dry grass. Some people were mad that headlines used the word “ex-con,” as if that made the rescue less; some were mad anyone would trust a stranger; some said this is what happens when you shut down rest stops and tell tired families to keep driving; some said gifts of gift cards and gas money and a motel room key showed up anyway, because hearts are better at ignoring arguments than minds are.

On the third day, a counselor asked Red if he would sit in on a play therapy session. “He keeps asking where you are,” she said. “You’re a safety signal. We can use that.”

He sat on a rug with stitched animals and watched Caleb line up toy cars and build a tiny canyon of blocks and push a matchbox SUV through it, slow, slow, slow, and then stop it before the edge. He waited to breathe until the car was safe and then realized he had forgotten to breathe for a full minute.

“Mom said if anything scary happens, look for a good man,” Caleb said, not looking up from the cars. “How do you know who’s a good man?”

Red considered the wrong answers and the tempting ones and the ones that would sound good on the evening news. “Sometimes,” he said, “a good man is just a man who doesn’t keep driving.”

The funeral was a week later in a small church with fans that clicked and a sign out front that still said “Potluck Saturday” because no one had the heart to climb a ladder. People came who didn’t know the family, because that’s what people do when something has reached them; they bring casseroles and an appetite for carrying weight that doesn’t belong to them because maybe one day someone will return the favor.

Rachel asked Red to say something. He stood at a pulpit that had seen better varnish and looked out over faces that wanted a certain kind of hero story and were ready to be given a different one.

“I wasn’t supposed to be there,” he said. “But a lot of things I wasn’t supposed to do are the only things I’ve ever been any good at. I don’t have a lot to give. But I had a truck that would start, and a rope that would hold, and two hands that could lift.”

He paused, found the boy’s eyes, found his own voice again.

“I didn’t save Caleb by myself. His mom saved him. The car took the worst part because she put her body where the danger was. And my part was just to finish her plan. We talk about second chances like they’re lottery tickets somebody else prints. Sometimes second chances are heavy. Sometimes they look like a kid you’re scared to love because you don’t trust yourself to be steady. But if life hands you one, you don’t say no because you’re afraid of who you used to be. You say yes, and then you hold on.”

After the service, a row of truckers idled along the curb; someone had organized a convoy. Each rig had a small ribbon tied to a mirror. Red’s truck looked like the poor cousin at a family reunion, but the drivers parted for him the way waves do for a boat with something sacred onboard. Caleb asked to ride the lap around the block in Red’s cab. Rachel said yes in a voice that learned how quickly yes and no can change the world.

It didn’t take long for the letter to find Red. It was an official thing with stamps and seals and words like “petitioner” and “guardianship” that made his tongue stumble. Rachel slid it across a diner table sticky with syrup rings. “I can’t be everywhere,” she said. “I want him with me. But I also want him with you, when it makes sense. I want the world to tell him that good men come in all kinds. You showed him that the first day.”

Red stared at the paper until the words steadied. “I don’t know how to do this,” he confessed.

“Neither do I,” she said, and smiled like surrender can be as brave as a fight. “But he asks for you when it gets dark. And when he sleeps at my house, he makes me leave the window open so he can hear the road.”

They worked out a plan that looked more like a handshake than a contract. Weekends at the aunt’s house where the grass actually grew; afternoons at the tire shop where Red swept bays and taught Caleb how to listen for the difference between a good bearing and a bad one. School counselors, check-ins, rules about buckling up and bedtimes. A new phone that could text. A small tent that fit them both the first time they took it to a state park and fell asleep to wind pushing at the canvas like a friend.

The first time someone recognized them at a rest stop, the woman cried and said, “You saved him.” Red looked at Caleb and said, “We keep saving one another,” and realized it was the truest sentence he’d said in a month.

By fall, a county task force invited Red to a meeting. They wanted to talk about search patterns and the places people ignore. “You saw a shoe where we saw a ditch,” a deputy admitted. “Maybe we need drivers who know what a lonely mile looks like.”

They wrote up a pilot they called the Shoulder Watch. Volunteer truckers and bikers agreed to take certain back roads once a week at low speed and write down anything that didn’t belong. A retired teacher knit orange hats for them because that’s what retired teachers do when they’re told there’s a gap between what is and what could be.

Caleb stood at the first briefing in a jacket too big, the sleeves rolled, a cast off, and explained in a clear voice how a shoe light can go out on a Tuesday, and even then someone might see it on a Wednesday if they’re willing to pull over.

“Five days,” he said, counting them on his fingers. “And then a man who wasn’t supposed to stop, stopped for me.”

He looked up at Red then, and Red felt the air go quiet the way it does when a room is listening to a promise being made.

Winter came with its clean light and its longer shadows. Red learned how to pack lunches that didn’t leak. He learned the names of teachers and which streets ran one way and how to sit in a school auditorium without his knee bouncing. He bought a pair of decent boots and a button-down shirt for the day a judge signed a piece of paper saying he was part of a boy’s life in a way no one could take away. He kept the shirt folded in the glovebox like a talisman against backsliding.

On Sundays, if the weather held, they drove. They took the long roads other folks avoided because “nothing out there” actually means “everything out there if you need the space.” Caleb picked songs. Red told stories about engines and mistakes and how to apologize to your own heart when you’ve made it carry weight it wasn’t meant to carry. They stopped for ice cream even when it was cold. They kept the windows cracked so the cab always smelled a little like the world.

Sometimes they found things. A girl who’d run from a fight and needed someone’s aunt to call. A hiker who’d turned one wrong time and had the good sense to sit still. A busted radiator that a gallon of water and luck would nurse to the next town. None of it made news. All of it mattered.

On the anniversary of the shoe, Red drove to the same mile and pulled onto the shoulder and turned the engine off and let the quiet say everything. He climbed down to the place where the brush still held small ghosts of thread. He said a thank-you he didn’t aim at any particular sky.

Back on the road, Caleb held the old sneaker they’d found the week after the rescue—the mate, stiff as cardboard, the lights forever asleep. He had drawn a small star on the white rubber with a marker.

“What’s the star for?” Red asked.

“So I don’t forget,” Caleb said.

“What?”

“That you can run out of light,” the boy answered, tapping the sneaker gently, “and still be seen.”

Red nodded and looked at the road unwinding ahead like tape being pulled from a roll, long and sticky and ready to fix the next thing that came loose. He felt the truck hum under him, steady. He felt the small weight of a boy leaning into his side when the lane drifted and the world tugged left, the way it always will.

“Seat belt,” Red said, automatically, affection in the warning.

“Buckled,” Caleb said, tugging it like a joke they’d tell each other until it was a habit neither of them could break.

They passed Mile 73, then 72, and the numbers kept sliding down like a kind of blessing, counting them not to an end but to the beginning of wherever they were going next.

And maybe the world didn’t change that day the way headlines promise. Maybe what changed was smaller, inside two people and the circles that touched them. A man found a thing he wasn’t sure he deserved: a chance to show up and keep showing up. A boy found proof that the road will sometimes answer back if you call it by your right name. A town found a way to ask better questions of the miles beyond its map.

Somewhere, a shoe light stayed dark forever.

Somewhere else, a truck’s turn signal clicked, and clicked, and clicked again, reminding anyone who cared to listen that the difference between going on and pulling over is sometimes the quietest decision in the world—until it isn’t.

Red checked the mirror. The lane behind them was empty, and in the glass he could see his own eyes, older and steadier than he remembered. He touched the brim of a cap he’d bought at a thrift store the week they realized “family” can be a verb.

“Where to now?” he asked.

Caleb didn’t hesitate. “Where someone might need us.”

Red smiled and eased the truck into the kind of wide, forgiving sky you only get out here, and the road unspooled like hope does—one honest mile at a time.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!