Part 1 – The Night a Sick Kid Tried to Hire a Veteran to Erase Him

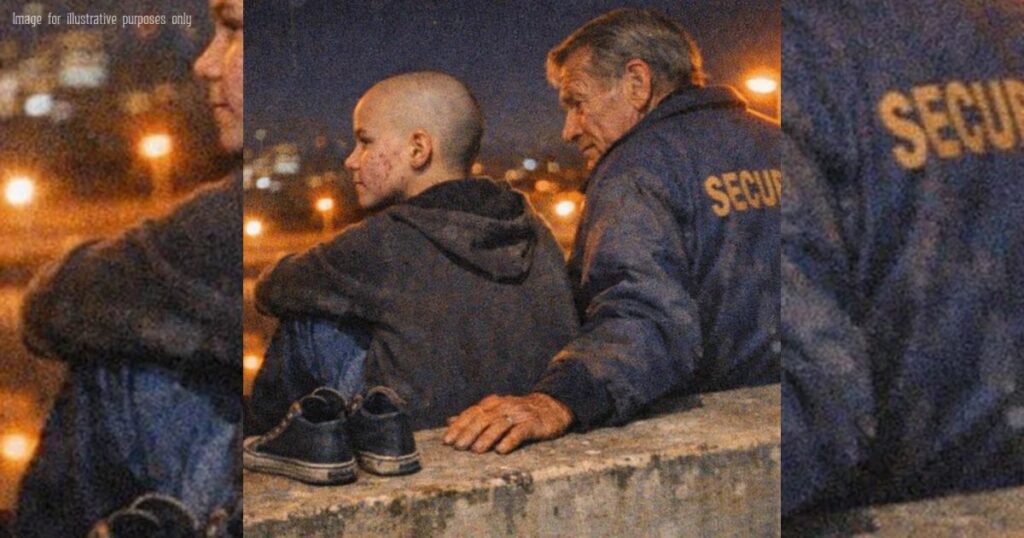

The night a tired veteran found a famous cancer kid sitting alone on the hospital roof, the boy tried to pay him to help him disappear, offering cards, passwords, and a future he no longer wanted.

By sunrise, the entire country would call that boy an inspiration, but in that moment he just needed one stranger to hear the truth: he was done being anyone’s miracle.

Caleb Ortiz spotted him because of the shoes.

Most kids in the pediatric wing wore bright socks and soft slippers, not black sneakers with the laces tucked in, toes pointed toward the edge of the rooftop garage like they were thinking about the air below.

The boy was a small shape against the concrete barrier and the orange glow of the parking lot lights, hunched into a gray hoodie, IV tape still on his arm.

No parent, no nurse, no phone in his hand. Just a metal lunchbox resting on his knees.

Caleb’s job description said “night security.”

He checked doors, walked the stairwells, made sure no one was sleeping in their cars.

It did not say “talk kids off roofs.”

But his feet moved toward the boy before his brain caught up, the same way they had moved toward wounded men in another life.

“Hey, kid,” Caleb said, keeping his voice soft and his distance wide.

The boy flinched, then twisted around.

The hood fell back, and for a second Caleb forgot how to breathe.

He knew that face from the posters in the lobby and the videos on the waiting room TV.

Mason Hale.

Fourteen.

He was the smiling kid in all the fundraising clips, the one who told the camera, “I’m not scared of the dark anymore,” while nurses cheered behind him.

Tonight there was no camera, and his big, hollow eyes did not look like they owed anyone courage.

“You’re the guard,” Mason said, squinting at Caleb’s badge.

“The one who walks like his bones remember bad weather.”

There was no smile on the words, just a tired observation.

“And you’re supposed to be upstairs,” Caleb answered.

“Lights out was an hour ago.”

He took another slow step closer, careful not to spook him.

Mason glanced down at the drop, then back at Caleb.

“You look like someone who knows when things are really over,” he said quietly.

“Not the way doctors say it. The way soldiers do.”

His gaze flicked to the patch on Caleb’s old jacket, the faded outline of a unit crest he never bothered to remove.

Caleb’s stomach tightened.

He had been trying for years to be just “the older guy with the keys,” not “the man who still woke up sweating from noises that sounded like helicopters.”

But kids in hospitals noticed more than adults thought.

They learned to read faces the way other kids learned to read comic books.

“I know what tired looks like,” Caleb said.

“That’s all.”

“What are you doing out here, Mason?”

Instead of answering, the boy lifted the metal lunchbox off his knees and popped the lid.

Inside, neat stacks of glossy cards gleamed under the rooftop lights, each one in a plastic sleeve.

Caleb saw dragons, planets, bright symbols he didn’t understand.

“These are Galaxia Battles cards,” Mason said, like he was reciting something important.

“First printings. Tournament promos. This one is Solar Dragon. People online say it’s worth more than a used car.”

His fingers shook, but he held the box toward Caleb like an offering.

Caleb stayed where he was.

“I don’t play card games,” he said.

“And I don’t take things from kids who should be in bed.”

Mason shook his head.

“It’s not just the cards.”

He swallowed.

“I have a channel. Videos. Streams. A lot of people watch. I know that’s not real money, but it can be. I can give you the login. You could sell the cards, use the channel, whatever you want.”

There it was, laid out between them in the cool night air: a payment.

Not in cash, but in everything a fourteen-year-old had ever built.

Caleb felt his ribs tighten around a heart that suddenly seemed too big for his chest.

“What exactly do you think I do, son?” Caleb asked, keeping his voice level.

“Because I’m the guy who unlocks the supply closet when someone forgets their badge. That’s pretty much the whole job.”

Mason’s eyes didn’t flinch.

“I think you know how to make things stop,” he said.

“Cleanly. Quietly. In a way that doesn’t send me back for another round of ‘let’s try one more thing’ while everyone smiles like this isn’t slowly wrecking them.”

His voice cracked, and for the first time, Caleb heard the boy under all the brave speeches.

Caleb’s mind flashed to another night, another high place, his own hands gripping a rail while the world below blurred.

He remembered the weight of someone else’s hand on his shoulder, a rough voice saying, “If you go now, you’ll never know what you almost had.”

The memory passed like a wave and left him standing again on this cold concrete, one old man and one very young.

“I’m not here to hurt you,” Caleb said.

“And I’m not here to help you hurt yourself.”

He stepped closer and sank down with a groan, sitting a few feet away, back against the barrier.

The roof felt harder than he remembered, but he wasn’t planning on leaving soon.

Mason stared at him, confused.

“No lecture?” he asked.

“No ‘think about your family’ speech? I’ve heard every version. They all end with, ‘be strong for us.’”

He looked back at the night.

“I’m tired of being something people point at when they need hope.”

“How long have you been sick?” Caleb asked.

He needed facts, something solid to hold on to.

“Six years,” Mason said.

“First time it was in my leg. Surgery, chemo, the whole thing. Then it came back in my lungs. Then in my spine. They say this new plan is aggressive. Sounds like a nice word for more days feeling like I’m not really alive.”

He touched the tape on his arm like it was an old scar instead of fresh.

Caleb listened.

He did not rush to fill the silence with promises he couldn’t keep.

He let the wind move between sentences and the hum of the city rise up from below.

In the distance, an ambulance siren wailed and faded.

“My mom believes every new treatment is a door,” Mason said.

“My stepdad believes in bills and numbers. I just…” He exhaled slowly.

“I believe in math. The odds keep getting worse, and the pain keeps getting longer. At some point it stops being about living and starts being about keeping other people from feeling like they gave up on me.”

He turned his head and studied Caleb’s lined face.

“So tell me the truth, not the hospital version. If I walk back inside and say yes to more… everything… can you promise it won’t just be months of hurting so other people can say they tried?”

His voice was almost a whisper.

“Can you promise it won’t be worse than just stopping now?”

Caleb looked at the boy, at the lunchbox full of shimmering cards, at the dark sky pressing down on all of them.

The answer formed in his chest, heavy and clear.

“No,” he said quietly.

“I can’t promise that. I’d be lying to you if I tried.”

He turned toward Mason, eyes steady.

“But I can promise you something else.”

Part 2 – The Veteran’s Promise

For a long moment, the roof was just wind and breathing and the distant murmur of traffic.

Mason watched Caleb like he was waiting for a verdict, like some part of him had already accepted there would be none that made sense.

The lunchbox of cards sat between them, a strange little treasure chest on gray concrete.

Caleb felt the weight of every year he had lived pressing down on his shoulders.

“I can’t promise you less pain,” Caleb said at last.

“I can’t promise the treatments won’t be rough or that the math will suddenly turn friendly. That would be a lie, and you’ve had enough of those.”

He shifted against the barrier, knees complaining, but he didn’t look away from the boy.

“What I can promise is this: you won’t have to perform for me. You won’t have to be brave, or inspiring, or anything but exactly what you are.”

Mason blinked, like he wasn’t sure he heard that right.

“Everyone says that,” he muttered.

“‘Just be yourself, honey.’ Then the camera turns on and they nudge me to say something about hope.”

His fingers traced the edge of the box as if he needed something solid under his hands.

“I’m not a camera,” Caleb said.

“And I’m too old to pretend I don’t see what’s right in front of me.”

He took a slow breath, the cold night air filling lungs that had once been clogged with dust and fear.

“Do you know what people used to call me, back when I wore a uniform?”

Mason glanced at the faded patch on his jacket.

“Sergeant? Doc? I don’t know.”

He shrugged, but his eyes were on Caleb now, not the drop beyond the wall.

“Some war nickname you all pretend to hate and secretly love?”

“They called me Lucky,” Caleb said.

“Not because I won anything, but because I kept not dying when everyone thought I should. Bullets missed by inches, explosions passed me over, illness skipped me and hit the guy in the next bed.”

He swallowed, the old tightness curling under his ribs.

“For a long time, I hated that name more than anything.”

“Because other people didn’t get lucky,” Mason said quietly.

He sounded like a kid who had spent a lot of time in rooms where people didn’t come back from surgery.

“Because you had to watch them go while you stayed.”

“Yeah,” Caleb answered.

“And because there was a point when I didn’t want to stay. There were nights when the idea of not waking up felt like a gift, not a tragedy.”

He watched Mason closely, making sure the words landed as truth, not as suggestion.

“One night, I stood somewhere high and thought very hard about stepping forward.”

Mason’s throat moved in a hard swallow.

“And?” he asked.

“What stopped you? Don’t tell me it was thinking about sunsets and puppies.”

“It was a hand on my shoulder,” Caleb said.

“A guy I barely knew sat with me the whole night. He didn’t tell me I was selfish. He didn’t tell me to count my blessings. He just said, ‘If you go now, you’ll never know what you almost had.’”

Caleb looked back at the boy, the light etching hollow shadows under Mason’s eyes.

“He didn’t promise it would get better. He promised he’d be there even if it didn’t.”

Mason let out a breath that sounded almost like a laugh and a sob tangled together.

“That’s the first honest answer I’ve heard in months,” he said.

“Everyone else keeps trying to sell me a happy ending. Or at least a noble one.”

He glanced down at his sneakers, toes still inches from the edge.

“So here’s my promise,” Caleb said.

“You can be furious. You can be tired. You can say you don’t want another needle in your skin. You can say you’re scared. You can say you’re done.”

He spread his hands, palms up, empty.

“And as long as I’m breathing, you won’t be saying any of that alone.”

The wind dragged at the hem of Mason’s hoodie.

He tightened it around himself like armor.

“What if I step back from here,” he said slowly, “and it just buys me more months of being a burden? More bills, more late notices, more people online telling me to ‘fight harder’ from their couches?”

His voice dropped.

“What if staying just makes everything worse for everybody?”

“You really think your mom would be better off with an empty bed?” Caleb asked, but his tone was gentle, not accusing.

“You think your stepdad would sleep easier knowing he didn’t get to see you roll your eyes at him anymore?”

He shook his head.

“Grief doesn’t send fewer bills just because someone leaves on purpose.”

Mason flinched, as if that cut sharper than anything else.

“But I’m not stupid,” he said.

“I hear them whisper. I see the envelopes. I know what experimental treatment costs. People keep saying I’m ‘worth it,’ like they have to convince themselves.”

He bit his lip until the skin blanched.

“How long does a kid get to keep taking up this much oxygen before it’s just selfish?”

Caleb resisted the urge to close the distance and grip his shoulders.

Touch was tricky with kids who’d spent years being poked and prodded.

“They chose you,” he said instead.

“They chose the early mornings and the late nights and the extra shifts. That doesn’t mean it isn’t hard, but hard isn’t the same as wrong.”

He pointed toward the stairs with a tilt of his head.

“And walking back down there tonight isn’t you choosing to hurt them. It’s you choosing to let them keep loving you.”

Mason was quiet for a long time.

Below them, someone’s car alarm chirped and fell silent.

A helicopter thumped far off in the city, a sound that made old scars itch under Caleb’s skin.

Finally, Mason drew his feet back from the edge, heels scraping on concrete.

“I don’t know if I can promise to keep choosing that,” he said.

“Not forever. Not if the next plan is just the same pain with better marketing.”

He looked at Caleb, face set with something older than fourteen.

“But I can promise I won’t decide anything big on a roof at midnight without talking to you first.”

Caleb nodded once, the knot in his chest loosening just enough to breathe.

“That’s all I’m asking for tonight,” he said.

“Not forever. Just not like this.”

He pushed himself up slowly, joints protesting.

“You think you can walk back in with me, or am I going to get yelled at by a nurse for not bringing a wheelchair?”

Mason snorted, a brief, crooked sound.

“I can walk,” he said.

“I’m not made of glass. Just… very cranky jelly.”

He closed the lunchbox with a soft click and hugged it to his chest.

They moved together toward the door, side by side.

Caleb stayed half a step behind, not pushing, not pulling.

As they reached the stairwell, Mason paused with his hand on the handle.

“Can I ask you something else?” he said without turning.

“Ask,” Caleb replied.

He could feel the question before it came, thick in the air between them.

“If I go back in there and say yes to another round of being poked and burned and tired,” Mason said, “I need you to promise me something that isn’t just about them.”

He inhaled sharply, as if dragging courage out of his lungs hurt.

“Promise me you won’t try to turn me into your project. Your chance to fix whatever you wish someone had done for you back then.”

He finally looked over his shoulder, eyes searching Caleb’s face.

“Promise me you’ll see me as me. Not as a second chance for some kid you lost or some version of yourself.”

Caleb held that gaze, feeling the sting of how precise the boy’s words were.

He had treated soldiers older than Mason who couldn’t name their fears half as clearly.

“I can promise you that,” he said.

“I’ve buried enough ghosts. I don’t need you to carry any of them for me.”

Mason closed his eyes for a heartbeat, then pushed the door open.

Warm hospital air washed over them, smelling like antiseptic and old coffee.

As they stepped inside, Caleb felt something shift, small but real.

The night hadn’t become less dark, but it no longer felt like it owned the whole sky.

Part 3 – Six Months, One Deal, and Too Many Cameras

The next morning, the posters in the lobby hit Caleb differently.

Mason’s face was everywhere, taped to donation boxes, printed on flyers, frozen mid-laugh next to slogans about courage and light.

It felt strange to see that bright, polished version after the rooftop boy who had counted himself a burden.

Stranger still knowing how many people loved the image without ever hearing the questions behind it.

In the cafeteria line, a nurse tapped her phone and turned the screen toward a coworker.

“New video went up,” she said.

“He did a Q&A about fear. My sister shared it and cried for twenty minutes.”

Caleb pretended he wasn’t listening, but Mason’s voice spilled out anyway, cheerful and edited, saying things about “choosing positivity” that sounded rehearsed now.

By the time Caleb reached the pediatric floor that evening, he had decided on one thing.

He needed to talk to Mason before the boy disappeared back behind that camera smile.

He cleared his visit with the charge nurse and knocked softly on the open door of Room 417.

Inside, cartoon planets danced on the walls, machines hummed, and a small galaxy of stuffed animals guarded the bed.

Mason lay propped up against a mountain of pillows, holding a tablet.

His mother sat in the armchair, laptop balanced on her knees, the glow turning her tired face a different shade of pale.

When she saw Caleb in the doorway, she blinked like she was trying to place him, then remembered the badge.

“You’re the night guard,” she said.

“I’ve seen you make the rounds.”

Her eyes flicked to Mason, then back.

“Everything okay?”

“We talked last night,” Mason said quickly.

“He found me when I was… getting some air.”

It wasn’t exactly true, but it wasn’t a lie either.

Caleb nodded, stepping just inside.

“I just wanted to check on him,” he said.

“Make sure he made it back to bed.”

He didn’t talk about rooftops or lunchboxes. That would be a different conversation.

Mason’s mom closed her laptop halfway, fingers still hooked on the edge.

“Thank you,” she said.

Her voice trembled on the last word in a way that made Caleb’s chest ache.

“I’m Patricia.”

They exchanged quick introductions, the polite kind people used in spaces where beeping machines filled in the rest.

Patricia mentioned how kind everyone at the hospital had been, how much support they’d gotten from strangers online.

“It’s the only reason we can still be here,” she admitted.

“The fundraiser, the channel, all of it. People have been very generous.”

Mason’s jaw tightened, just barely.

Caleb noticed, but Patricia didn’t.

She reached over and smoothed her son’s blanket, a gesture that looked automatic, like breathing.

“Doc says they’re considering a new protocol,” Mason said.

“Some trial. Sounds like a fancy way of saying ‘more medicine we’re not sure about.’”

His eyes flicked to Caleb, and something passed between them that Patricia couldn’t decode.

“We’ll talk to the team tomorrow,” Patricia added quickly.

“We don’t have to decide anything yet. We just have to listen.”

Her gaze bounced between her son and the door, like she was expecting answers to walk in on a clipboard.

After a few more polite minutes, Caleb excused himself.

He waited until he was back in the hallway, out of earshot, before he leaned against the wall and blew out a breath.

He had been a medic long enough to recognize the mix of hope and exhaustion on Patricia’s face.

It was the look of someone who had built their whole world around one fragile possibility.

That night, his supervisor stopped him near the elevators.

“Heard you spent some time with Hale’s kid yesterday,” she said.

“Family mentioned you were up on the garage.”

Her tone wasn’t hostile, but it wasn’t casual either.

Caleb kept his expression neutral.

“He was alone,” he said.

“I made sure he wasn’t anymore.”

“I appreciate that,” she replied.

“But we do have protocols. If a patient seems distressed, you’re supposed to notify staff. We have counselors, social workers…”

She trailed off, then added, “You’re here to keep doors locked and strangers out, Ortiz. Not to take on the whole world.”

Her words were fair.

They still stung.

For a second, he saw himself from her angle: an aging guard with a limp, hovering around a vulnerable kid, stepping outside his lane.

He nodded, taking the rebuke without argument.

“I understand,” he said.

“I’ll loop you in next time.”

He meant it too, mostly.

He just wasn’t sure what “next time” would look like.

It came more quickly than he expected.

Two nights later, Mason texted him from an unknown number.

Caleb only knew it was him because the message read, “Is your promise still good, or was that a rooftop-only special?”

Caleb stared at the screen, then typed back, “Still good.”

A few seconds later, another bubble appeared.

“They want me to sign up for the trial,” Mason wrote.

“Mom says it’s a door. The doctor says it’s a chance. My math says twenty percent maybe, eighty percent more rough days. I need to make a deal.”

Caleb found an empty visitors’ lounge and sat down, his knees grateful for the chair.

“What kind of deal?” he replied.

He could almost hear the boy’s breathing between the ding of messages.

“Six months,” Mason wrote.

“If I say yes to this trial, I want it to be our six months, not theirs. Not the internet’s.”

There was a pause, then, “You help me make sure I’m not just content for other people to share. You help me say no when I need to. You sit with me when it’s bad. After six months, if everything still feels like torture with no point, we talk again. For real. No sugarcoating.”

Caleb read the words twice.

There was no mention of rooftops or edges, but the shape of them was there, hiding in the white space.

He pictured the boy weighing treatments like battle plans, and something in him clenched.

“I can do that,” he answered.

“I can’t control the trial. I can’t control the outcomes. But I can sit next to you while they happen. And I can remind you that your life is more than what ends up on someone’s screen.”

He hesitated, then added, “And when six months is up, we talk, no matter what.”

Mason sent a simple reply.

“Deal.”

The next day, during the meeting with the oncology team, Caleb stayed out of the room.

It wasn’t his place to sit at that table.

He watched families come and go past the glass, faces tight, hands squeezed together.

When Patricia stepped out afterward, she looked like someone had taken her heart out, weighed it, and put it back wrong.

“They think it could help,” she told him when their paths crossed by the elevator.

“Or at least give us more time to see if it helps. I don’t even know what I’m agreeing to anymore. I just know I’m afraid of doing too little and afraid of doing too much.”

She laughed, a short, helpless sound.

“Is there ever a right answer, Mr. Ortiz?”

“If there is, I haven’t met it,” Caleb said honestly.

“All we get are better questions and people to sit with while we ask them.”

It felt like a thin comfort, but it was the only kind that had ever held up under pressure.

That evening, when Caleb stepped into Room 417, Mason was awake, wires trailing from under his hospital gown.

The lunchbox sat on the tray table, closed.

No cameras were visible, no lights or microphones.

Just the boy and the beeping monitor and the question hanging in the air.

“I signed,” Mason said before Caleb could speak.

He tapped the inside of his elbow where fresh tape held a line in place.

“Welcome to Trial Number I-Lost-Count.”

He studied Caleb’s face.

“You still in?”

Caleb pulled up the chair and sat down, joints cracking like worn hinges.

“I’m in,” he said.

“For six months. For more if you’ll let me.”

He nodded at the lunchbox.

“And I’m not taking that as payment. But you’re going to have to explain why the dragon is so special, or I’m going to be very confused the next time someone calls it priceless.”

Mason’s mouth twitched.

“That’s Solar Dragon,” he said.

“It was the first rare I pulled after my diagnosis. Before the channel. Before the sponsorships. Just me and my best friend trading cards on his bedroom floor.”

His fingers brushed the metal box.

“Back when being alive didn’t feel like a job I could get fired from.”

“Then for the next six months,” Caleb said softly, “your job isn’t to be anyone’s symbol. Not mine, not the hospital’s, not the internet’s. Your job is to be Mason.”

He leaned back, letting the monitors beep around them like distant birds.

“And I’ll be right here learning what that actually means.”

Mason looked at him for a long second, then nodded once.

“Okay,” he said.

“But you should know something before we start this.”

His eyes hardened with a different kind of resolve.

“If anyone tries to turn this trial into a cute video about being brave, I’m going to ruin their footage.”

Caleb almost smiled.

“That,” he said, “is the best math I’ve heard all day.”

Part 4 – The Night the Hero Kid Broke the Script

The first week of the trial felt less like medicine and more like a storm building.

Small side effects gathered on the horizon: nausea, headaches, a strange metallic taste that made even water feel wrong.

Mason tried to joke about it, calling it “level-one boss fights,” but his eyes gave away how quickly his energy was draining.

Caleb sat through the long hours between doses, listening to the machines breathe with him.

Doctors came and went with charts and careful voices.

They talked about numbers and markers and responses, always with that studied calm they wore like a uniform.

Sometimes their words landed like raindrops on glass and slid right off.

Sometimes they cut.

Between appointments, life outside the curtain tried to keep moving.

Messages piled up on Mason’s tablet from followers, classmates, distant relatives.

You’re so strong.

Keep fighting.

You’re the bravest person I know.

Caleb watched him scroll through them during a quieter afternoon.

The boy’s thumb flicked down the screen, past hearts and fire emojis and “praying for you” comments.

“What do you see when you read those?” Caleb asked.

“People who mean well,” Mason said.

He didn’t sound angry, just distant.

“But also people who don’t really want to hear the answer if I say, ‘Actually, I’m not strong. I’m exhausted, and sometimes I’m angry that my bones feel older than yours.’”

He set the tablet aside.

“If I say that, they send longer messages explaining why I shouldn’t feel what I feel.”

“They’re scared,” Caleb said.

“They don’t know what to do with your honesty, so they try to talk it into something prettier.”

He knew that reflex too well. He’d watched people do it to veterans for decades.

“Doesn’t mean your feelings are wrong.”

Three days into the protocol, Mason’s manager from the channel arrived.

It was a cousin on his mother’s side, a young man with nervous energy and a backpack full of equipment.

He talked fast, about viewers and engagement and how “authentic content” was trending.

“I’m not filming during treatments,” Mason said flatly.

He tugged his blanket higher, cheeks pale from a long morning.

“If you want a brave speech, go download one of the old clips. I’ve done plenty.”

“It doesn’t have to be a speech,” the cousin replied.

“It can be just you, talking about how this trial is giving you hope. People will relate. They want to see the real journey.”

He smiled like this was all a collaboration.

“The real journey?” Mason’s eyebrows lifted.

“The real journey is me trying not to throw up on my shoes and wondering if my family will have a house next year. You want to film that?”

His voice trembled, not with weakness but with anger.

Patricia looked torn in the corner, hands twisting in her lap.

“The donations do help,” she said softly.

“It’s not about fame, honey. It’s about keeping the lights on.”

She glanced at Caleb, as if hoping he might have the right words.

Caleb wished he did.

He understood needing help. He understood bills that seemed to multiply overnight.

He also understood what it felt like to have your pain turned into a story other people consumed and then walked away from.

“What if tonight,” Caleb suggested, choosing his words carefully, “you film something that’s not about hope or bravery or any of those big words?”

He looked at Mason.

“What if you talk about exactly what you said. That you’re tired. That you’re scared. That this is complicated.”

The cousin frowned.

“That might upset people,” he said.

“They come to the channel to feel encouraged. To see victory.”

“Then maybe they need to see what it costs,” Mason replied.

His hands were shaking now, but he didn’t look away.

“If this is really about helping us, they should be able to hear more than speeches that make them feel good.”

They argued in circles for a while.

In the end, a compromise formed, messy and fragile.

One short live stream.

No prewritten lines.

No cutting away if things got uncomfortable.

The camera went live that evening, a small red light blinking in the corner of the room.

Mason sat up straighter, adjusting his pillow.

His hair had started to thin again, a subtle reminder of the chemicals working their way through him.

Caleb stood out of frame by the window, where the reflection in the glass showed enough to let him see without intruding.

“Hey, everyone,” Mason said.

His voice was quieter than in past videos, but steady.

“It’s been a while. I’m still here. Still at Riverside. They’ve got me on a new plan that sounds like something from a science fiction movie.”

He managed a crooked smile.

Comments poured up the side of the screen.

We missed you!

You’ve got this!

Look at you smiling through it all!

Mason glanced at them, then back at the lens.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about what people want to see,” he continued.

“They say they want honesty. But usually, what gets the most likes is when I say I’m not scared, or when I talk about ‘choosing joy’ no matter what.”

He paused, swallowing hard.

Caleb watched his shoulders rise and fall.

He could feel the room holding its breath, even though the audience was miles away behind their own screens.

Patricia sat in the armchair, hands clasped so tightly her knuckles were white.

“Tonight I’m going to tell you something different,” Mason said.

“Tonight I’m going to tell you that I am scared. A lot. I’m scared of the pain, and I’m scared of the bills, and I’m scared of everyone looking at me like I’m brave when sometimes I just feel… trapped.”

His voice cracked on the last word.

The comment feed exploded.

Some wrote hearts.

Some wrote, It’s okay to be scared.

A few lines blurred past too quickly for Caleb to catch, but he saw enough to know the tone had shifted.

“I don’t want to be anyone’s symbol tonight,” Mason said.

“I don’t want to be the kid you point to when you need motivation to go to the gym or forgive your neighbor or whatever. I’m just a teenager who misses riding his bike and not knowing what his blood counts are.”

He lifted his eyes, glassy but fierce.

“And it’s really, really hard.”

Patricia’s tears spilled over, silent tracks down her cheeks.

The cousin hovered by the laptop, looking between the numbers ticking up and the boy on the bed, clearly torn between the storm he had helped summon and the reality of it.

Caleb stayed still, hands in his pockets, feeling like he was watching a bridge being crossed in real time.

A long silence followed.

You could almost hear the thousands of viewers breathing on the other side of the screen.

Then Mason took a deep breath.

“If you’re watching this because you love me, thank you,” he said.

“If you’re watching because my story makes you feel stronger, I hope tonight you also hear that strength doesn’t mean smiling all the time. Sometimes it means saying, ‘I’m not okay,’ and letting that be true for a while.”

He reached out and tapped the button to end the stream.

The screen went dark.

In the quiet that followed, the beeping of the monitor sounded strangely loud.

No one moved.

Then Patricia stood and crossed the room in two quick steps.

She wrapped her arms around her son, careful of the lines and tape, and held on.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered into his hair.

“I’m so sorry I didn’t see how heavy this got for you.”

Mason trembled, hands fisting in her shirt.

“I don’t want to disappoint everyone,” he said.

“That’s the worst part. I’m tired and I’m scared and I still feel like I owe people a show.”

His words broke something in Caleb that he hadn’t realized was still rigid.

Later, when the cousin had packed up the camera and left and Patricia had gone to get coffee, Mason stared at the blank tablet screen.

“They’re going to be mad,” he said.

“Some of them. They always are when I say something that doesn’t fit the happy story.”

“Some will be,” Caleb agreed.

“Some people get upset when the world refuses to arrange itself into their favorite kind of movie.”

He pulled the chair closer.

“But some kid somewhere is going to hear what you said and breathe out for the first time in weeks, because they thought they were the only one who felt that way.”

Mason thought about that, eyes unfocused.

After a moment, he looked over.

“Do you think the hospital is going to be mad?” he asked.

“Like, ‘stop saying it’s hard, it makes the walls look bad’ mad?”

“If they are, they can talk to me,” Caleb said.

“I’ve seen walls do just fine standing next to the truth.”

He leaned back, letting his weight settle.

“Besides, the way I see it, you just did something braver than any speech they ever put on a poster.”

Mason huffed out a breath that was almost a laugh.

“Braver or just more likely to lose us sponsors?” he said.

He rubbed his eyes with the heel of his hand.

“Either way, I’m too tired to think about it tonight.”

As the lights dimmed and the hallway sounds faded, Caleb stayed in the corner chair, watching the rise and fall of the blanket.

He knew tomorrow would come with fallout.

Emails, opinions, maybe meetings in offices with neutral paint.

But for now, in this small room, something had shifted.

The boy who had once tried to hire a stranger to erase him had just told the world he was not okay and refused to turn it into a slogan.

Caleb wasn’t sure if that would break him or save him.

Maybe, he thought, it would do a little of both.

Part 5 – After the Stream, the Silence

The backlash arrived faster than the morning rounds.

By the time Caleb clocked in for his shift the next day, nurses were already talking in the hallway, phones in hand.

Some had tears in their eyes; others had tight, worried expressions.

Words like “raw” and “controversial” floated under the fluorescent lights.

In the staff lounge, someone had pulled up the replay before it was taken down.

A small group watched with furrowed brows as Mason said he was tired of being an example.

A social worker repeated, “We need to check in with him soon,” like a mantra.

Caleb was glad to hear it, even as it twisted his gut.

By mid-afternoon, the family’s fundraiser page was filling with comments.

Most were supportive.

A few said they admired Mason’s honesty.

But there were others, sharp-edged and impatient.

“If you give up, what was all our help for?” one wrote.

“People raised money, you owe it to them to fight,” another added.

Someone else typed, “Thousands of kids would kill for the chance you’re throwing away,” then deleted it and replaced it with something only slightly softer.

Patricia read some of them in the hallway, her back pressed to the wall.

Caleb watched her face go pale, then flush, then crumble in tiny ways she tried to hide.

She handed the phone back to the cousin managing the page.

“Maybe we should turn comments off for a while,” she said quietly.

“That could upset people,” he replied.

“They’ll think we don’t appreciate them.”

He hesitated.

“But… yeah. Maybe. Just for a bit.”

While the adults argued over settings and optics, Mason slept through most of the morning.

The trial was taking its toll, knocking him flat for longer stretches.

When he finally woke up, he blinked against the sunlight leaking around the curtain.

“Did I start a revolution or a disaster?” he asked Caleb, voice rough from sleep.

“Or both?”

He shifted slowly, wincing, and reached for the water cup.

“Depends who you ask,” Caleb said.

“Some people think you told the truth. Some think truth should come with a warning label.”

He handed the cup over.

“None of that changes what your body is going through, though.”

Mason sipped and sighed.

“How mad is my mom?” he asked.

“On a scale from ‘grounded’ to ‘you can never see the Wi-Fi again’?”

“She’s not mad at you,” Caleb said.

“She’s mad at a world that makes a fourteen-year-old feel like telling the truth might be a betrayal.”

He tilted his head.

“And she’s scared. Because somewhere along the line, money and medicine got braided together in ways no parent ever signed up for.”

Later that day, the oncologist called for a family meeting.

They gathered in a small conference room with a table too big for their number and a box of tissues already open in the center.

Caleb waited outside at first, but Patricia caught his sleeve.

“Would you mind staying?” she asked.

“He listens to you. And… I don’t always understand everything the doctor says the first time.”

Her eyes begged for backup.

Caleb hesitated, then nodded.

He took a seat near the wall, out of the direct circle but close enough to catch every word.

Mason rolled in in a wheelchair, blanket over his legs, lunchbox balanced on his lap like a shield.

The doctor went over the early numbers from the trial.

They were not disastrous.

They were also not the kind of immediate improvement some families prayed for.

“There are some encouraging signs,” he said carefully.

“But this is a long process. We’ll need more time to see if the response is meaningful.”

Mason stared at the graphs.

“To translate,” he said, “my body is deciding whether it wants to cooperate or be a stubborn mule.”

His mouth twitched.

“Story of my life.”

“We also need to talk about expectations,” the doctor continued.

“This treatment is intense. There will be difficult days. We have support staff available for emotional and mental health as well as physical side effects.”

He glanced at Mason, then at Patricia.

“I saw the video last night.”

Patricia flushed.

“I’ve already told my cousin we’re pulling it down,” she said quickly.

“We never wanted to cause trouble for the hospital.”

The doctor shook his head.

“I’m not here to scold anyone,” he said.

“I’m glad he felt able to express himself. It’s important we know when patients are struggling so we can help.”

He folded his hands.

“But we do want to make sure he has safe spaces for those conversations, not just public ones.”

Mason raised an eyebrow.

“Safe meaning what?” he asked.

“Rooms with couches and pamphlets? I know the drill.”

“Safe meaning places where you can say, ‘I’m angry and I’m tired and I don’t know if I can do this,’ without hundreds of strangers reacting in real time,” the doctor replied.

“We can’t carry you through this if we don’t know where you are. But we also don’t want anyone feeling like they’re on stage when they need to be vulnerable.”

The honesty surprised Caleb.

He’d expected something more rehearsed, gentler around the edges.

Instead, the doctor sounded like a man trying very hard not to pretend.

It eased something inside him.

After the meeting, when they were back in the room, Mason turned to his mother.

“Can we stop filming for a while?” he asked.

“I know the money helps. I know people love us. But I can’t keep performing my pain for likes.”

His voice shook, but his gaze was steady.

Patricia looked at her son, really looked, past the lines and the machines and the cloud of worry.

She saw the kid who used to build forts in the living room and demand extra sauce on his pizza.

She saw the boy who now sometimes whispered in his sleep, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” for things he couldn’t control.

“Yes,” she said, the word coming out before she could overthink it.

“We can stop. We’ll figure something else out.”

Tears spilled over, but her shoulders dropped like a weight had rolled off them.

“I’m sorry it took you saying it in front of the whole world for me to hear it.”

That night, donations slowed.

A few regular contributors sent messages saying they understood the break from content and would keep helping.

Others drifted away silently, their attention moving on to other stories.

The internet rarely stayed in one place for long.

Bills did not drift away.

They arrived on schedule, crisp and impersonal, numbers marching across paper.

Patricia sat at the small family table in the room, calculator in hand, brow furrowed.

Mason watched her from the bed, guilt gnawing like an old, familiar animal.

“I could go back on for a few short videos,” he offered.

“Nothing heavy. Just updates. People like knowing what’s happening.”

He tried to sound casual, but the effort showed.

Patricia shook her head, wiping at her eyes.

“No,” she said.

“You shouldn’t have to trade pieces of your heart for help. We’re not doing that anymore.”

She took a breath.

“We’ll talk to the social worker. We’ll look at grants. We’ll ask family. We’ll be honest about needing help without putting a camera in your face while you hurt.”

Caleb felt his chest tighten with something like pride.

This was not a neat, inspirational moment.

There was fear at the edges and uncertainty all through the middle.

But there was also a kind of courage he trusted more than the poster version.

A few days later, new lab results came back.

They showed small progress in one area, setbacks in another.

The doctor used words like “mixed picture” and “too early to draw conclusions.”

It was the kind of news that left everyone in the room unsure whether to breathe out or hold their breath tighter.

That night, as Caleb walked his rounds, his phone buzzed.

A text from Mason popped up.

“Hey. What happens if we get to the end of six months and nothing feels worth it?”

Caleb stopped in an empty stairwell, leaning against the cool rail.

He read the question three times, feeling the weight in every word.

He thought of promises made on rooftops and in hospital rooms, of deals he’d agreed to without knowing where they would lead.

He typed back slowly.

“If we get there, we talk. Really talk. With doctors. With the counselor. With your family. With me. We look at all the options together. You won’t be alone with that question.”

He hesitated, then added, “And we might find that along the way, the question changes.”

There was a long pause before the dots appeared.

“What if it doesn’t?” came the reply.

Caleb looked at the blank steps stretching above and below him, thinking of all the years he’d spent climbing in the dark.

He chose his response with care.

“Then I will still be there,” he wrote.

“I can’t promise you answers. I can promise you I won’t run away from the hard ones.”

No reply came right away.

Caleb slipped the phone back into his pocket and continued his rounds.

Behind every door he passed, lives were unfolding in all their messy, unphotogenic ways.

Some would make it onto screens. Most would not.

Hours later, as the night pressed deeper against the windows, his phone buzzed again.

A single message glowed on the screen.

“Okay. I’ll keep walking a little longer.”

Caleb stared at those words until they blurred.

He knew they were not a happy ending.

They were a step, one careful foot in front of the other, on a road with no guaranteed finish line.

It would have to be enough.

Part 6 – The Text That Didn’t Answer Back

The infection came on like bad weather, slow enough to ignore at first and then all at once.

One day Mason was dragging himself through another round of meds, the next he was shivering under three blankets, skin hot and eyes glassy.

Caleb noticed the change before the chart did, not because he was a doctor, but because he had spent years watching men crash in strange ways.

He knew the look of a body losing ground.

By evening, nurses were moving faster around Room 417.

They spoke in clipped phrases, hanging new bags, adjusting lines, calling out numbers that made Patricia’s face go blank.

Mason drifted in and out, mumbling things that didn’t quite make sense.

When he was lucid, his messages turned short and sharp.

“Feels like my bones are on fire.”

“If this is what hope costs, it’s a bad bargain.”

The last one came just before midnight, when Caleb was halfway through his rounds.

“If our six months ends here, was any of this worth it?”

Caleb replied as soon as he saw it.

“I don’t know yet. But we’re not done counting days. I’m coming up after this floor.”

He quickened his pace, checked the last few doors, and headed for the pediatric wing.

By the time he stepped off the elevator, the hall outside Mason’s room was different.

The easy chatter was gone, replaced by a hum of urgency.

A nurse hurried past him with a medicine tray, eyes focused and jaw set.

At the door to 417, a sign had been taped up: Isolation Precautions.

“Family only right now,” a nurse said when he tried to step closer.

Her voice wasn’t unkind; it was just firm.

“Infection risk. He’s very sick. We need to limit who goes in.”

“I’m not family,” Caleb said.

The words tasted wrong in his mouth, like admitting to a lie he hadn’t realized he was telling himself.

“Just… let his mom know I’m out here, okay?”

She nodded and disappeared behind the curtain.

Caleb backed up until he found a chair against the wall.

He sat, hands clasped, watching shadows move under the door.

The next hour blurred.

He heard Patricia’s voice, high and tremulous, somewhere inside.

He heard the steady commands of the night doctor, the crisp responses of nurses.

He thought of field hospitals long ago, tents flapping, men cursing or praying under their breath.

At some point, a chaplain walked by and gave him a nod of recognition.

“Family?” the man asked.

“Friend,” Caleb answered.

“Kind of.”

“Sometimes that’s the quieter word for family,” the chaplain said.

He squeezed Caleb’s shoulder once and moved on, summoned by someone else’s emergency.

Caleb checked his phone.

No new messages.

He scrolled up through the earlier ones without meaning to—jokes about hospital food, little vents about annoying tests, the late-night confession: “I’m tired of being a symbol.”

The last text sat at the bottom of the screen like a dropped stone.

He thought about going outside to pace, but some part of him was afraid that if he moved, he would miss something.

Instead, he sat under the fluorescent lights and tried to breathe in a slow count.

In through the nose, out through the mouth, like the therapist at the veterans’ center had taught him.

Eventually, the door opened.

Patricia stepped out, mask hanging loose under her chin, hair shoved back with both hands.

Her eyes were red, but there was still focus in them.

“They’re moving him to the intensive care unit,” she said.

“Infection. His pressure dropped. They’re doing everything they can.”

Her voice wobbled, but she didn’t collapse.

“Is he awake?” Caleb asked.

His own voice sounded far away.

“Not really,” she said.

“They gave him medicine to help his body rest while they fight the infection. He knew my name for a minute.”

She bit her lip.

“He asked if you knew the deal was still on.”

Caleb swallowed hard.

“He got my last message,” he said.

“Tell him I’ll be wherever they let me be. Outside the door, if that’s what it takes.”

The ICU had its own rules.

Only a few minutes of visiting every hour.

Masks, gowns, sanitizer until your skin felt raw.

Caleb wasn’t on the list at first, and that pinched more than he wanted to admit.

“You’ve already done so much,” Patricia told him gently.

“You don’t have to put yourself through this too.”

“I know,” Caleb said.

“I’m choosing to.”

He hesitated.

“Like he did.”

She stared at him for a moment, then nodded.

“I’ll talk to the nurse,” she said.

“Maybe they can bend the rules a little. He keeps asking about ‘the guard with the bad knee’ when he’s in those half-awake moments. I think… I think you matter to him.”

Later that night, Caleb found himself in the waiting area outside the ICU, a smaller, quieter limbo.

A television in the corner played muted news.

Someone had left a stack of magazines on a table, their glossy covers jarring against the heavy air.

A familiar voice broke through his thoughts.

“Ortiz?”

He looked up to see a man about his age in a worn denim jacket, a baseball cap pulled low.

“Tanner,” Caleb said, recognizing one of the men from the veterans’ support group that met in the hospital basement on Tuesday nights.

“What are you doing up here?”

“Friend’s boy had a bad asthma attack,” Tanner replied.

“Been sitting with them a few hours.”

He studied Caleb’s tired posture.

“You look like somebody whose past is running into his present again.”

Caleb huffed a humorless breath.

“Kid I’ve been… hanging around with. Trial patient. Infection hit hard,” he said.

“He’s in there fighting, and I’m out here with my thumbs in my pockets.”

“That’s the problem with surviving,” Tanner said.

“You get real good at watching other people fight while you’re stuck holding coffee cups and pens.”

He sat down across from Caleb, knees cracking.

“Want to come downstairs for a bit? Guys are still around. Hospital coffee is free if you don’t ask what’s in it.”

Every instinct in Caleb said stay put.

Stay by the door, stay within sprinting distance, even if there was nowhere for him to run.

But another voice, older and steadier, reminded him of the oxygen mask rule from flight safety cards.

You can’t help anyone if you’ve forgotten how to breathe.

He nodded reluctantly.

“Just for a few minutes,” he said.

“If they need me, they’ve got my number.”

The room in the basement was small, with mismatched chairs and a box of tissues on every flat surface.

Posters about stress and healing decorated the walls.

A coffee pot sat on a side table, half full and probably too strong.

“Hey, Lucky,” someone called as he walked in.

He winced at the nickname he’d once worn like a curse.

It had stuck in this group after he accidentally let it slip during introductions.

“Don’t start,” he said, but there was no real heat in it.

He dropped into a chair and leaned forward, elbows on his knees.

Tanner made the introductions quick.

“This is the kid guy,” he told the others.

“Trial treatment, been talking him off the internet edge for a while.”

They didn’t ask for details.

They’d all been around enough hospital corridors to fill in the blanks.

Instead, they took turns sharing brief, blunt things about nights they thought they wouldn’t see morning and mornings they’d wished hadn’t come.

When it was Caleb’s turn, he surprised himself by talking.

He talked about the rooftop with Mason, about the lunchbox of cards, about the six-month deal they had made.

He admitted he was terrified of failing this kid the way he’d felt he’d failed others.

“You’re not his savior,” one of the older vets said quietly.

“You’re his witness. There’s a difference.”

He tapped his chest.

“People like us spend a lot of time wishing someone had stayed long enough to see us. You’re doing that. That matters.”

Another man, younger, with tattoos peeking out from under his sleeves, spoke up.

“My little cousin went through something like that,” he said.

“Not cancer, but bad stuff. He told me once the worst part wasn’t the pain. It was feeling like everyone had already decided what his story should mean.”

He picked at a crack in the table.

“If your kid—sorry, the kid—makes it through this, maybe that’s something he can help change.”

Caleb listened, nodded, let the words sink in.

It didn’t make the fear go away.

But it gave it edges he could lean against instead of drowning in.

When he went back up, the ICU hallway felt a fraction less suffocating.

A nurse met him with an update.

“His numbers are still rough,” she said.

“But he’s holding. Infection’s bad, but the antibiotics are strong too. Next twenty-four hours are important.”

“Can I see him?” Caleb asked.

“I’ll gown up. I won’t stay long.”

They made an exception.

Someone had written his name on a small list taped to the door: Mother, Stepfather, Caleb (security).

It looked strange there, official and fragile at once.

Inside, the room was dim, lit by monitors and a small lamp.

Mason lay still, cheeks flushed with fever, chest rising and falling in shallow rhythm.

Tubes and wires snaked from his arms, his nose, the machines around him.

Caleb stepped closer until he could see the little frown between the boy’s brows, like he was arguing with someone even in sleep.

He wanted to say something profound, something that would penetrate whatever fog Mason was under.

Instead he settled for the simple.

“Hey, kid,” he whispered.

“It’s me. The guard with the bad knee.”

He touched the rail of the bed, knuckles white.

“You don’t owe anybody a miracle,” he said softly.

“Not this hospital, not those people on the screen, not me. You don’t owe us a victory story.”

He swallowed, feeling the burn behind his eyes.

“But if you’ve got one more round in you, one more day of letting us love you, I’m asking you to take it. Not for the posters. For you.”

The monitors beeped on, indifferent to speeches.

Mason didn’t wake up, didn’t squeeze a hand, didn’t give any cinematic sign.

He just breathed, a little uneven but steady, as the medicine did its work.

Caleb stood there until the nurse tapped his shoulder and pointed to the clock.

Visiting time was over.

He stepped back, the gown rustling, and left one final promise in the air behind him.

“Whatever happens when you wake up,” he said, “I’m still here. Deal or no deal. Hero or just a kid who’s had enough. I’m not going anywhere.”

Part 7 – Things We Wish You Knew

Mason’s fever broke two days later, not with a triumphant moment, but with the quiet recalibration of numbers.

The graphs on the screen shifted from alarming red to cautious yellow.

His breaths evened out.

His fingers twitched around the edge of the blanket like someone rediscovering the weight of his own skin.

When he finally opened his eyes, the room was blurry.

Voices filtered in: his mother’s whisper, a nurse’s professional calm, the low rumble of Caleb’s tone somewhere near his feet.

For a moment, he didn’t know if he was at the beginning of something or the end.

“Hey,” Patricia said, leaning over him.

“You’re back.”

Her smile trembled, but it was real.

Mason’s throat was dry.

“Did I go somewhere?” he rasped.

He tried to clear his voice and coughed.

“You took a short vacation in Sleepy Town,” Caleb said from the corner.

He stepped into view, mask dangling from one ear now that the immediate crisis had passed.

“Ten out of ten do not recommend the travel package.”

“Is… the trial over?” Mason asked.

He hated how small his voice sounded.

“Did we lose?”

The doctor stepped in then, as if summoned by the question.

“Not necessarily,” he said.

“The infection was a complication. A serious one. But your body fought it off with some help. That’s not nothing.”

He looked at the monitors.

“As for the trial, we need to reassess. Carefully. With you.”

They moved Mason out of ICU and back to a regular room a few days later.

He was weaker than before, every movement a negotiation.

But he was also more awake, more aware of the fragility of the bargain he’d made with his own life.

One afternoon, a hospital counselor named Dana visited.

She was in her forties, wore sensible shoes and a badge that said “Behavioral Health,” and carried a notebook she didn’t open right away.

She pulled up a chair and sat like she had all the time in the world.

“I saw the live stream you did,” she said.

“And I heard about the infection. That’s… a lot in a short time.”

She smiled gently.

“I’m here because it might help to have someone whose job is listening.”

Mason eyed her warily.

“Are you going to tell me to think positive?” he asked.

“Because I’ve hit my quota for that word this year.”

“No,” she said.

“I’m going to ask you what you wish people would stop saying. And what you wish they would say instead.”

She rested her elbows on her knees.

“Not just about you. About kids like you.”

That question lit something behind Mason’s eyes.

He glanced at Caleb, who nodded as if to say, Go on.

He took a slow breath.

“I wish they’d stop calling us warriors like that fixes anything,” he said.

“I wish they’d stop posting pictures of us with tubes and then writing paragraphs about how WE taught THEM to be strong, like our job is to improve their day.”

His fingers knotted in the blanket.

“I wish someone would ask what hurts that isn’t in the lab work.”

Dana wrote nothing down.

She just listened.

“And if they did ask?” she said.

“What would you tell them?”

Mason stared at the ceiling, counting the dots in one panel.

“I’d tell them I’m scared my little brother is going to grow up thinking I loved the hospital more than him,” he said.

“I’d tell them I feel guilty every time my mom pays for parking.”

His voice thinned.

“I’d tell them some days I don’t want to be inspiring. I just want to complain like a normal teenager and not have anyone hold their breath.”

Caleb felt the words land like stones in a pond, rippling outward.

He thought of his own unspoken wishes from decades ago—that someone would admit war made no sense, that survival sometimes felt like losing, that you could love your country and still hate the things it asked of you.

“What if we made a list?” Dana said quietly.

“Not just yours. Others too. ‘Things We Wish You Knew.’ We could ask some of the other teens, if they’re up for it. No cameras. No posting without clear consent. Just a list for staff, for parents, for anyone who works with kids like you.”

Mason’s eyebrows went up.

“Like a manual?” he asked.

“A guide to not making us feel like walking posters?”

“More like a translation,” she replied.

“From your language into the one adults understand.”

She glanced at Caleb.

“Maybe we even involve a certain night guard who knows a thing or two about being turned into a symbol he didn’t ask to be.”

Caleb shrugged.

“I can carry paper,” he said.

“And say when something sounds like it came from a brochure instead of a person.”

Over the next week, as Mason regained some strength, Dana returned with blank pages and open questions.

She talked to other teens on the floor—a girl who’d missed prom, a boy who kept his guitar in his room, a quiet kid who only spoke when his mother left.

They each contributed a sentence or two.

“I wish you wouldn’t whisper in the hall and then smile too wide when you walk in.”

“I wish you’d ask before touching my stuff.”

“I wish I didn’t feel like my grades mattered more than my feelings.”

“I wish you’d stop telling me how strong I am when I’m just very practiced at not crying in front of you.”

They added practical things.

Don’t promise there won’t be pain.

Don’t say “this won’t hurt a bit” when it will.

If you don’t know the answer, say you don’t know.

Mason watched the list grow, his own handwriting scattered among the others.

“This feels important,” he said one evening.

“Like maybe if people read this, the next kid who comes in won’t feel as crazy for feeling what they feel.”

Caleb nodded.

“In my first year back home, I would’ve paid good money for a list like that,” he said.

“‘Things We Wish You Knew About Coming Home From Somewhere That Changed You.’ Might have saved a few holes in drywall.”

He smiled faintly.

“Maybe we can still write that one too.”

Patricia read the draft one night while Mason slept.

By the third line, tears blurred the words.

“I had no idea,” she whispered.

“I mean, I knew he was hurting. But some of this… I didn’t see it.”

“That doesn’t mean you failed,” Caleb said.

“It just means he was busy trying not to make it harder on you.”

He hesitated.

“Kids can be real sneaky that way. So can veterans.”

They printed copies and gave them to the nurse manager, who agreed to share them at the next staff meeting.

“I can’t promise everyone will change overnight,” she said.

“But it’s hard to ignore words written this clearly by the people we’re supposed to be serving.”

The six-month mark crept closer, even as time inside the hospital felt stretchy and unreliable.

Some days the trial’s impact showed up in small victories—slightly better numbers, a little more energy.

Other days it felt like every step forward came with two backward.

One night, Mason asked for the lunchbox.

He opened it slowly, tracing the edge of Solar Dragon’s sleeve.

“Do you ever think about the night we met?” he asked Caleb.

“About that edge?”

“Every time I walk past that garage,” Caleb said.

“Every time my knee hurts on those stairs.”

He watched Mason’s face.

“Do you?”

“Yeah,” Mason said.

“Sometimes I wonder what would’ve happened if you’d called security instead. Or if I’d never looked up when you said ‘hey, kid.’”

He swallowed.

“Sometimes I still wonder if I should’ve just stepped.”

Caleb didn’t flinch away from the words.

He let them hang between them, heavy and honest.

“Do you wonder that more or less than you used to?” he asked softly.

Mason considered.

“Less,” he admitted.

“Not because the pain is less. It’s not. But because now when I think about leaving, I don’t just think about escaping. I think about what gets left undone.”

He tapped the stack of papers on the bedside table—the draft of “Things We Wish You Knew.”

“I think about other kids reading this and maybe not feeling so alone.”

“So the question changed,” Caleb said.

“It’s not just ‘is it worth staying for me?’ It’s ‘is it worth staying for what I might leave behind.’”

He nodded slowly.

“That’s not a bad question to have.”

Mason leaned back against his pillows, eyes on the ceiling.

“I don’t know how many years I’m going to get,” he said.

“None of us do. But I think… I think I want however many I get to mean something that isn’t just numbers on a chart.”

His voice steadied.

“If that means more trials, more shots, more days like this, I’ll… I’ll think about it. Really think. Not just react.”

Caleb watched him, feeling both protectiveness and respect twist together in his chest.

“You know the deal still stands,” he said.

“At the end of six months, we talk. Not about promises you made on a rooftop or things you said in a video, but about what it feels like in your bones.”

He paused.

“And whatever you feel, I’ll listen. Even if I don’t like it.”

Mason smiled faintly, eyes drifting shut.

“Good,” he murmured.

“Because I’m getting very good at saying uncomfortable things.”

The list on the bedside table fluttered in the air from the vent, its top line visible in the dim light.

Thing #1: We are not your lessons. We are your kids. Treat us like people, not stories.

Part 8 – The Choice No One Could Make for Him

Six months to the day after Mason and Caleb had made their rooftop deal, the doctor spread a new set of charts across the foot of the bed.

The lines were different now.

Not a miracle, not a straight climb, but a measurable shift away from the cliff’s edge.

Words like “partial remission” and “maintained response” made cautious appearances.

“It’s not a cure,” he said, because he had learned not to dress news up too much.

“But it is movement. And in this situation, movement matters.”

He looked Mason in the eye.

“We have options now. More than we did when we started.”

Mason’s legs ached, his back hurt, and his energy was a fraction of what it had been before the trial.

He’d lost weight he didn’t have to spare.

He had gained scars, both visible and invisible.

Hearing the word “options” felt like standing at a crossroads with blurry signs.

“What kind of options?” he asked.

He wanted specifics, not platitudes.

“We can continue with a modified version of this protocol,” the doctor said.

“Less intense, focused on maintaining the response we’ve seen. We can consider a different supportive treatment plan. We can even, if you and your family decide it’s time, shift to care that focuses only on comfort and quality of life without aggressive interventions.”

He folded his hands.

“That choice would not be giving up. It would be a valid decision based on your values.”

Patricia inhaled sharply.

Her stepfather’s hand found hers, squeezing tight.

They looked at Mason as if afraid to influence him with their faces.

“How long do I have if we keep going?” Mason asked.

He knew there were no exact answers, but he needed to hear the shape of things.

The doctor exhaled.

“Everyone is different,” he said.

“With continued treatment, we hope for years, not months. There are risks of complications, but also the possibility of seeing this disease stay quiet for a long time.”

He didn’t say “growing up,” but the idea hovered.

“And if we don’t?” Mason’s voice was calm.

“Then we focus on keeping you as comfortable as we can, for as long as your body allows,” the doctor replied.

“We would expect a shorter timeline. But we would work very hard to make that time meaningful and as pain-controlled as possible.”

He paused.

“I won’t put numbers on it in this room, not unless you really want them. They can change, and sometimes they do more harm than good.”

Dana, the counselor, sat in a corner chair, watching the conversation with quiet attention.

Her presence reminded everyone that this was not a math problem.

It was a heart problem, a fear problem, a hope problem.

Caleb stayed near the wall, as he had in so many briefings in his life.

He had listened to commanders outline plans and probabilities before.

Soldiers rarely got to decide if they wanted to be in the fight.

This boy did, and the weight of that freedom made Caleb’s chest tight.

“Can I think?” Mason asked finally.

“I mean, really think. Not just today. Over a few days. Maybe with a notebook.”

He glanced down at his hands.

“I don’t want to answer just because I’m scared or because someone looks at me a certain way.”

“You should think,” the doctor said.

“You should ask questions. You should talk to whoever you need to.”

He smiled faintly.

“This is your body and your life. We’ll walk whichever road you choose with you.”

After they left, the room felt both bigger and smaller.

The machines were quieter now, the infusion pumps less frequent.

Mason stared at the ceiling, then at Caleb, then at the “Things We Wish You Knew” pages stacked by the window.

“Remember the deal?” he said.

His voice was hoarse but steady.

“Six months. Then we talk.”

Caleb pulled the chair close to the bed and sat, joints creaking.

“I remember,” he said.

“I haven’t forgotten a single word since that night.”

“I thought the choice would be easier,” Mason admitted.

“I thought either I’d be so sick I’d know it was time, or I’d be suddenly better and obviously keep going.”

He gave a small, humorless laugh.

“I didn’t think we’d land in the middle like this.”

“Most of life happens in the middle,” Caleb said.

“The movies just cut those parts out.”

He rested his forearms on his knees.

“What does your middle feel like right now?”

Mason considered.

“It feels like… like I’m hanging from a rope over a canyon,” he said slowly.

“And someone told me I’ve got just enough strength to either climb a little higher or let go and land somewhere softer than the rocks.”

He shrugged.

“I’m trying to figure out if the climb is worth the blisters.”

They talked for a long time.

Not about numbers or charts, but about small things.

About the way his little brother had started drawing superheroes with bald heads.

About how Patricia had begun humming again when she folded laundry.

About letters Mason had received from other kids who wrote, “I thought I was the only one who was tired.”

“Do you want more of that?” Caleb asked at one point.

“Not more pain. More of this life. More bad jokes. More chances to say the things you’ve been saying that make other people feel less alone.”

He didn’t push.

He just put the question on the table.

“I do,” Mason said, almost surprised at himself.

“I want more of my brother. More of my mom’s pancakes when she’s not so stressed she forgets the sugar.”

He touched the edge of Solar Dragon’s sleeve, peeking from the lunchbox.

“I want to see if I can get old enough that this card looks silly in my wallet instead of like a trophy.”

“But?” Caleb prompted gently.

“But I don’t want every day between now and then to be nothing but hospital lights and nausea,” Mason said.

“I don’t want to disappear into treatments so completely that the only thing anyone remembers about me is my disease.”

He took a deep breath.

“I want to study something if I can. Learn something that isn’t how to read lab results. Maybe help kids like me someday. That sounds… big. Too big. But I think about it.”

“It doesn’t sound too big to me,” Caleb said.

“It sounds like you just described a life. A hard one, sure. But a real one.”

He tilted his head.

“Do you think continuing treatment is the only way that life might exist?”

Mason closed his eyes for a minute.

When he opened them, there was something new in his gaze.

A kind of quiet decision, not dramatic, but solid.

“I think if I stop now, everything becomes about my ending,” he said.

“Every conversation. Every look. Every day.”

He swallowed.

“If I keep going, maybe there’s a chance the story shifts to something in the middle again. I don’t know if my body can do it. But I want the chance.”

Caleb nodded slowly.

“Then that’s your answer,” he said.

“Not yes because they want you to. Not no because you’re tired. Yes because you have something you still want to aim at.”

He leaned back.

“And if at some point that changes, we revisit. Deals can be updated. That’s part of being alive.”

Mason let out a shaky breath.

“Tell my mom,” he said.

“No, I’ll tell her. But stay when I do, okay?”

He smiled weakly.

“I might need someone to pinch me if I start turning it into a speech.”

The conversation with Patricia and the stepfather was messy in the way honest talks often are.

There were tears and what-ifs and confessions of fear from all sides.

Patricia admitted she had been terrified of wanting her son to keep fighting because she didn’t know if it was for him or for herself.

Mason confessed he’d been scared of saying he wanted to try again in case his body betrayed him.

In the end, they agreed on a plan.

Continue treatment, but with safeguards.

Built-in breaks.

Mandatory sessions with Dana.

Clear boundaries around filming and fundraising.

“We survive this as people, not as a brand,” Mason said, surprising even himself with the firmness in his voice.

“If I make it to eighteen, I want to recognize myself when I look back. Not just see a highlight reel.”

Caleb thought of a night long ago when someone had put a hand on his shoulder and told him he’d regret not seeing what almost could have been.

He thought of all the years since: the good, the ugly, the quiet mornings that had turned out to be worth more than any medal.

As he walked his rounds later, he paused at the entrance to the rooftop garage.

The memory of that first night with Mason moved through him like a cold wind.

He didn’t go up.

He didn’t need to.

The boy who had once tried to hire him to erase his life had just chosen, in front of witnesses, to keep writing his own pages.

Caleb knew nothing was guaranteed.

He knew there would be more bad days.

But he also knew this: for the first time, the deal wasn’t about bargaining with death.

It was about bargaining with life, messy and painful and unfinished as it was.

Part 9 – The Boy Who Stayed and the Man Who Watched

Three years later, the hospital lobby looked different.

The paint was a slightly brighter shade, the chairs had been replaced, and the posters had changed.

There were still fundraising flyers, still photos of patients, but the tone was quieter.

More about listening, less about slogans.

On one wall, in a simple frame, hung a page titled “Things We Wish You Knew.”

Underneath, smaller print read, Written by patients and families of the Riverside Pediatric Unit.

Visitors paused sometimes to read it.

Nurses passed it every day and caught new lines they swore they hadn’t seen before.

Caleb stood in front of it, hands in his pockets, reading the top line again.

He never got tired of that sentence.

He had watched it be born from a boy’s frustration and practiced courage.

“You stare at that thing like it’s a painting,” a voice said behind him.

“Aren’t you supposed to be checking doors or scaring teenagers off the vending machines?”

He turned to see Mason, taller now, leaning on a black cane.

His hair had grown back in uneven waves.

A faint scar traced his jaw where a biopsy had once been.

He wore a button-down shirt and jeans instead of a hospital gown.

“Teenagers are a lost cause,” Caleb said.

“I’ve downgraded to inanimate objects. They’re easier.”

He took in the sight of the young man in front of him, a mixture of pride and a softness he didn’t have words for.

Mason moved carefully, but he moved.

The trial had not given him the body of a healthy eighteen-year-old.

There were still follow-up visits, still pills in little plastic cups, still days when his bones ached like weathered wood.

But he was not in a bed, and the disease that had once filled every corner of his life now shared space with other things.

He was taking online classes in psychology.

He volunteered twice a week in a peer support program the hospital had started for teens with chronic illness.

He had helped design it, along with Dana and a small group of staff and patients.

“I saw the new video,” Caleb said as they walked slowly toward the elevator.

“The one they show to new nurses.”

He nudged Mason’s shoulder gently.

“You look almost respectable.”

“Don’t spread that rumor,” Mason replied.

“I have a reputation to maintain.”

He shifted his grip on the cane.

“At least now when people say I’m an inspiration, they’re talking about something I chose to do, not just my immune system throwing a tantrum.”

The peer program’s first training video didn’t feature Mason hooked up to machines.

It showed him sitting in a circle with other teens, talking about how silence from adults hurt more than awkward questions.

It showed clips of him explaining why telling a kid “you’re so brave” is less helpful than saying “it’s okay to be scared.”

Doctors watched it in conference rooms.

Parents watched it in orientation sessions.

Some cried.

Some took notes.

“Three years,” Caleb said.

“Does it feel like a lifetime or like last week?”

“Both,” Mason answered.

“Every time I walk into the lab and smell the antiseptic, it feels like yesterday. But then my brother sends me a picture from his school dance, and I realize how much time actually passed while we were counting blood cells.”

He pressed the elevator button.

They rode up to the rooftop garage together.

Caleb’s knee complained on the short walk, but not enough to stop him.

Mason’s steps were careful, the cane tapping a steady rhythm.

When they reached the old spot, the concrete barrier was the same.

The view of the city lights hadn’t changed much.

But the boy who had once sat perched on the edge of it was now standing a safe distance away, hands resting on the rough surface.

“This is where you tried to hire me,” Caleb said.

He didn’t sugarcoat it.