Skip to Part 2 👇👇⏬⏬

I am a criminal. I haven’t broken any laws, I haven’t held up a bank, and I certainly don’t have a record. But make no mistake: I am a thief.

I have robbed the only two people in this world who would gladly lay down their lives for mine.

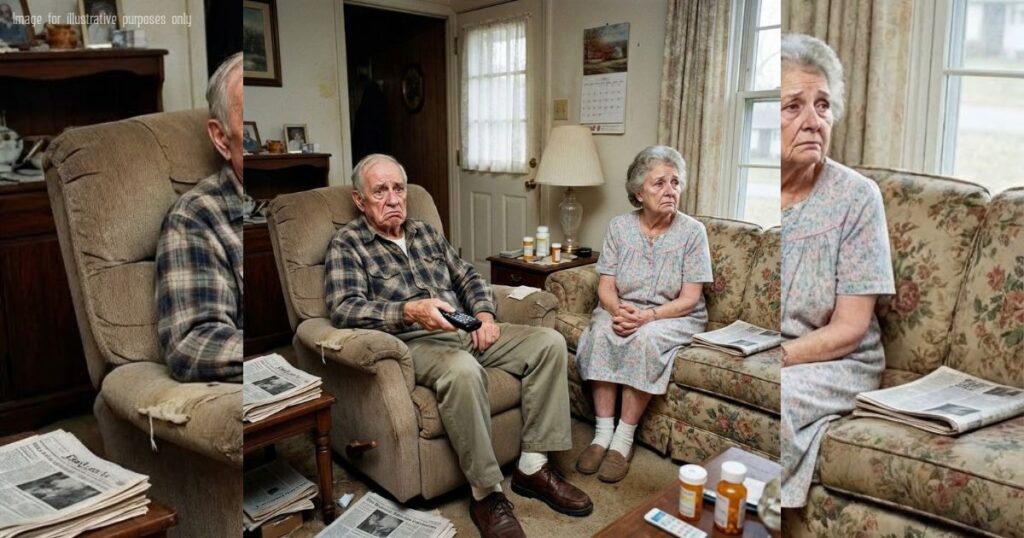

My father is a man who spent forty years breathing in sawdust and diesel fumes at the auto plant, a man whose hands are permanently stained with the grease of American industry. Today, he struggles to figure out which remote turns on the cable news.

My mother is a woman who once stretched a single pot roast to feed a family of five for three days, a woman whose laugh used to rattle the windows during our chaotic Fourth of July barbecues. Today, she gets winded just walking to the mailbox to check for letters that never come.

And I? I am the one stealing their oxygen. I am the thief of their time.

I don’t do it out of malice. I do it out of “importance.” I live three states away, in a glass-and-steel metropolis where “busy” isn’t just a state of being—it’s a trophy we polish every morning. I have a mortgage that feels heavier than gravity, two teenagers who speak in TikTok trends, and a corporate calendar painted in anxiety and deadlines.

I tell myself I am a “good son.”

I call every Sunday at 5:00 PM sharp (usually while multitasking on mute).

I send the premium flower arrangement for Mother’s Day (ordered via an app in 30 seconds).

I pay for the landscaping guy so Dad doesn’t have to mow the lawn.

But deep down, I know the truth. I am trading money for mercy. I give them my scraps. My rushed voicemails. My digital likes on their blurry Facebook photos. I have convinced myself that providing for them is the same as being with them.

I was wrong.

Last month, a client meeting in Pittsburgh got cancelled at the last minute. I found myself with a rental car, a cancelled flight, and a gaping hole in my schedule. My parents live about three hours west, in a small Rust Belt town that time seems to have forgotten.

I didn’t call ahead. I just drove.

I pulled onto Elm Street around 2:30 in the afternoon. It was a Tuesday. The sky was that crisp, piercing blue you only get in the Midwest during autumn. The sun was blazing.

And that’s when I saw it.

There, on the front porch of the house where I learned to walk, the light was on.

Not a motion sensor. Not a solar garden light. It was the old, yellow bug-light next to the front door. The one inside the rusted brass cage. It was glowing, fierce and completely pointless, fighting a losing battle against the afternoon sun.

I sat in my idling rental car, gripping the steering wheel, flooded with a sudden, irrational irritation. The “efficient” project manager in me wanted to scream.

“Dad, electricity rates are up 12% this year! Why are you burning money?” I could hear my own voice in my head, full of the arrogant logic of my generation. “Mom, you’re wasting energy!”

I parked, but I didn’t get out immediately. I just watched that stubborn, yellow bulb.

I am 48. My father is 86. My mother is 84. Their world, once as big as the factories and the community halls and the church picnics, has shrunk. It has contracted to the four walls of that bungalow. The fishing trips are gone. The bridge club friends have mostly passed on. The VFW hall, where Dad used to drink cheap beer with men who understood the silence of war, is now a trendy coffee shop.

Their life is now the living room, the doctor’s waiting room, and that front porch.

When I finally walked up the driveway, they didn’t hear me. The TV was too loud inside—some daytime court show blaring. I opened the screen door and stepped in.

Mom gasped and dropped a towel. She looked at me with a terrifying mixture of joy and confusion, as if she were seeing a ghost. Pop tried to launch himself out of his recliner, his knees cracking audibly, a grimace of pain crossing his face before he masked it with a smile.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he wheezed, his eyes instantly rimmed with red. “Look who decided to show up.”

We spent the next few hours doing absolutely nothing. And it was everything.

I ate a sandwich I wasn’t hungry for—bologna on white bread, a taste that transported me back to third grade. I listened to Dad talk about the neighborhood squirrels as if it were breaking geopolitical news. I fixed the settings on Mom’s iPad.

As evening fell, the house grew quiet. The silence in the homes of the elderly is different. It’s heavy. It’s composed of ticking clocks and the hum of the refrigerator.

I stood by the kitchen sink with Mom while she dried the dishes. Through the window, I could see the porch light, now actually useful as the twilight set in.

“Mom,” I asked, trying to sound casual. “When I pulled up today… at 2:30 in the afternoon… why was the front light on?”

She stopped drying the plate. She looked out the window, her gaze fixing on that yellow glow. She smiled, but it wasn’t a happy smile. It was a smile of infinite, weary patience.

“Because, honey,” she whispered, “someone might be coming home.”

The air left my lungs.

She didn’t say “We knew you were coming.” Because they didn’t. She didn’t just mean me.

She meant my sister in Denver who is “swamped” with her startup. She meant the grandkids who are “too busy” studying for finals. She meant the neighbors who used to wave but moved away. She meant the ghosts of the friends they’ve buried.

That light wasn’t a utility. It was a lighthouse.

It was a beacon burning on the edge of a lonely ocean, signaling to a world that had moved on: “We are still here. We are waiting. The door is unlocked.”

A single flick of that switch was a daily, defiant act of hope against the crushing silence of solitude.

I realized then that my parents aren’t just “old.” They are lonely in a way that my generation, with our 5,000 Facebook friends and constant notifications, cannot comprehend.

We possess the technology to connect with anyone, anywhere, instantly. Yet, we have left the people who built us stranded on an analog island.

I stayed the night. I slept in my old twin bed with the lumpy mattress. The next morning, I watched them. really watched them. I saw the way they both looked up—a micro-second of heartbreaking anticipation—every time a car drove past the window. I saw how Dad, a man who once led a strike for better wages, now waits by the phone like a teenager, hoping for a text back from a grandson. I saw how Mom keeps a list of things to tell me on the fridge, written months ago, just in case I call for more than five minutes.

They don’t want my money. They don’t want the expensive fruit baskets. They don’t want a new iPad. They don’t want me to “fix” their aging bodies.

They just want me.

They want to hear the heavy thud of my boots in the hallway. They want to listen to me complain about the traffic or the price of gas. They want to sit in the same room, in comfortable silence, and watch Wheel of Fortune. They want my time. The undivided, non-multitasking, phone-in-your-pocket time.

The truth is, parents never stop being parents. Their bodies fail, their world shrinks, their memories fray, but the job description never changes. Their job is to wait. To keep the light on. To hold the line until we return.

Our job is to notice.

So, if you are reading this on your phone, perhaps scrolling while you ignore the world around you, please stop.

If you are lucky enough to still have them—those aging, slow, frustratingly analog people who wiped your nose and paid for your college and worried when you were late—do not wait.

Don’t wait for Thanksgiving.

Don’t wait for a birthday.

Don’t wait for a “good time.” There is no good time. There is only time.

And for God’s sake, do not wait for the funeral.

Go to them. Go on a random Tuesday. Drive the car. Book the flight. Just show up. Sit on the scratchy sofa. Eat the stale cookies. Listen to the story you have heard twenty times before, and listen to it as if it’s the first time.

Look at their hands. Map the veins. Memorize the sound of their laugh.

Because I promise you, a day is coming—sooner than you think—when you will turn the corner onto their street. And the porch light will be off. The house will be dark.

And you will realize, standing on that silent sidewalk, that you are no longer a son or a daughter. You are an orphan. You will stare at that dark window and you will barter with God, with the Universe, with the empty air. You will offer every dollar in your bank account just to see that pointless, yellow bug-light hum to life one last time.

You will beg for five more minutes to walk through that door and say, “I’m home.”

Don’t be a thief like me. Go home. The light is on.

Part 2 — The Light I Tried to Turn Off

Two weeks after I told you, “Don’t be a thief like me. Go home. The light is on,” I did what thieves do best.

I went back to stealing.

Not with a crowbar. Not with a mask. With an Outlook notification and a fake smile on a video call.

Monday morning, my city swallowed me again—glass towers, gray sidewalks, a lobby that smelled like expensive coffee and anxiety. My calendar refilled itself like a bathtub you forgot to turn off. The world didn’t clap because I’d had a moral awakening in a Rust Belt bungalow. No one cared that I’d seen my mother’s hope glowing behind a bug-light in the middle of the afternoon.

The machine kept moving.

And if you’ve lived long enough inside that machine, you know the most dangerous part isn’t that it’s cruel.

It’s that it’s normal.

I told myself the same lie I’d been telling for years:

I showed up. I did the visit. I’m good now.

Like love is a punch card.

Like you can clock in once a quarter and still call it family.

That Tuesday, my mother left me a voicemail.

Her voice was bright—too bright. The way a person sounds when they’re trying not to sound lonely.

“Hi, honey! No rush. Just… calling to tell you I made that soup you liked. The one with the little noodles. It came out good. Your dad said it tastes like ‘the old days.’” A pause. A small laugh. “Anyway… we’re fine. Call when you can.”

Then, softer—almost to herself:

“And the light’s on, okay?”

I stood in my office, surrounded by people who looked busy in ways that could be photographed and praised, and I felt something hot crawl up my throat.

Because my mother wasn’t saying, Call me.

She wasn’t saying, I miss you.

She wasn’t saying, Please don’t forget us.

She was saying:

We are still here.

And I realized something that should’ve been obvious but wasn’t:

You can leave a house.

But you don’t leave the waiting.

That night at dinner, my wife asked how my parents were doing.

I started to say, “They’re fine,” out of habit.

But the word tasted like a lie.

“They’re… small,” I said instead.

My son didn’t look up from his phone.

My daughter, half listening, said, “Can’t they just move closer? Like… why do they stay there if it’s so sad?”

I wanted to snap. I wanted to launch into a speech about pride and roots and the weight of a life built with hands, not hashtags.

But then I caught myself, because here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Her question was logical.

That’s what makes this whole thing controversial. That’s why people fight about it in comment sections until their thumbs cramp.

Because on paper, the “solutions” are clean:

Move them.

Downsize them.

Put them somewhere “nice.”

Hire help.

Install devices.

Schedule calls.

Automate love.

But human beings aren’t spreadsheets.

My father is not a logistics problem to solve.

My mother is not a project to manage.

They are two souls who built a life inside four walls, and the world keeps telling them—politely, efficiently, with a smile—that their life is now an inconvenience.

That’s what my daughter was really saying, without knowing it.

Why don’t they make it easier for us to love them?

And maybe you’re reading this thinking:

Well… why don’t they?

Because the older I get, the more I understand:

For some parents, that house is the last place they still feel like themselves.

It’s not just a property.

It’s a time capsule.

It’s the hallway where your height marks are still on the trim.

It’s the kitchen table where your mother used to cut your pancakes into shapes.

It’s the porch where your father once sat at midnight waiting for you to come home from a date, pretending he “just couldn’t sleep.”

When you ask them to leave, you’re not asking them to change an address.

You’re asking them to abandon the last evidence that they mattered.

So I did the thing that terrified me.

I opened my calendar, stared at the weeks stacked like bricks, and I made a decision that would anger a lot of people and comfort a lot of others, depending on what kind of son or daughter you are.

I blocked off a random Thursday and Friday.

No “reason,” no “event,” no holiday to hide behind.

Just time.

Then I told my kids, “You’re coming with me.”

My son groaned like I’d announced we were moving into a cave.

My daughter said, “Do we have to?”

And there it was—another truth people don’t like to say out loud:

Grandkids don’t miss grandparents the way grandparents miss grandkids.

Not because they’re bad kids.

Because they’re kids.

They’re built for forward motion. For future. For new.

My parents are built for memory. For past. For keeping the light on.

Different worlds. Different physics.

The drive felt like crossing a border.

The skyline thinned. The lanes widened. The billboards changed from luxury to survival. The air looked older.

Halfway there, my son finally put his phone down and stared out the window.

“Dad,” he said, quiet, like he didn’t want to admit curiosity, “is this… where you grew up?”

“Yeah.”

He watched a rusted water tower slide past like a ghost.

“Was it… boring?”

I almost laughed.

“It was loud,” I said. “In a different way.”

When we pulled onto Elm Street, my heart did that stupid thing again—the tightening, the bracing.

And there it was.

Mid-afternoon.

That same pointless yellow light, glowing like a stubborn promise.

My daughter whispered, “It’s on again.”

My son didn’t make a joke.

He just stared.

Inside, my mother did the same gasp—like joy hurts when it’s unexpected.

My father did the same performance of strength—pushing himself up like his knees weren’t screaming, putting on that grin like a uniform.

“Well I’ll be damned,” he said, and his voice cracked just enough to make me hate myself all over again. “Look at this. The whole crew.”

My daughter hugged my mom the way teenagers hug—quick, awkward, like embarrassment is a currency.

My mother didn’t care. She held on anyway.

My father shook my son’s hand like he was greeting a man, not a kid, and my son looked startled by the weight of that respect.

We sat in the living room.

We did nothing.

And it was not boring.

It was… strange.

Because my kids live in a world where silence is punished. Where every empty second must be filled with sound, content, noise.

But in that bungalow, silence wasn’t empty.

It was full of presence.

My father asked my son about school. My son answered in short sentences, guarded.

Then my father said, “You ever change a tire?”

My son blinked. “Uh… no.”

My father nodded like that was both expected and tragic.

He looked at me. “You teach him?”

I opened my mouth, ready with excuses.

Busy. Work. City.

But my son answered first, surprising both of us.

“No,” he said, almost defensive. “But… I could learn.”

My father’s face did something I will never forget.

It softened.

Not like an old man indulging a child.

Like a father who has been waiting to pass something on.

He tried to take us out to the garage—his kingdom. The place where he used to fix anything with a wrench and sheer will. But two steps down the back stairs, his knee buckled and he grabbed the railing too hard.

I moved toward him.

He waved me off.

“I’m fine,” he said, which in father-language means: Don’t look at me too closely. Don’t make me real.

So we stayed inside.

My mother made soup.

Yes, that soup.

She placed bowls in front of us like she was feeding soldiers. Like nourishment was still her love language, even if her hands shook a little when she carried the spoon.

My daughter ate in silence.

Then she said, out of nowhere, “Grandma… why is the light always on?”

My mother froze for half a second, then smiled—gentle, tired.

“So someone can find home,” she said.

My son frowned. “But you don’t even know if anyone’s coming.”

My father looked at him, eyes sharp.

“That’s the point,” he said.

And listen—here’s where the story stops being sweet and starts being uncomfortable.

Because my son, in his own way, was right.

This hope costs something.

Electricity. Effort. Emotion.

Waiting is not free.

It takes a toll.

And this is where families fracture: not because people don’t love each other, but because love gets measured in different currencies.

Some people measure love in sacrifice.

Some in boundaries.

Some in survival.

Some of you reading this are thinking:

I would do anything for my parents.

Some of you are thinking:

You don’t know my parents. You don’t know what they did.

And both can be true.

Not every parent is safe.

Not every childhood deserves a reunion.

Not every “go home” is a holy thing.

But if your parents were good—if they were the kind who showed up, who tried, who failed sometimes but loved you anyway—then here’s the part that should make you sit up:

They are not waiting for your perfection.

They’re waiting for your presence.

That night, after my parents went to bed, my kids sat on the old couch and stared at the framed photos on the wall—me in a little league uniform, my sister with braces, my mom with hair that wasn’t gray yet, my dad standing tall in a work jacket like the world couldn’t touch him.

My daughter whispered, “Dad… you were cute.”

My son said nothing, but he kept looking.

Then, softly, my son asked, “Do they… always look up like that?”

“What?”

“When a car drives by,” he said. “Grandma keeps… looking.”

I felt my throat tighten.

“Yeah,” I admitted. “They do.”

My son swallowed. “That’s… rough.”

Welcome to it, kid, I thought.

Welcome to the part of life nobody films.

The next morning, my father shuffled to the front door before I was fully awake.

I heard the chain rattle. The screen door squeak.

Then a sound—small, wrong.

A thud.

Not dramatic. Not cinematic.

Just the sound of age meeting gravity.

I ran.

He was sitting on the porch step, pale, embarrassed more than hurt, gripping the railing like it had betrayed him.

“I’m fine,” he said immediately, because of course he did.

My mother appeared behind me, her eyes already wet.

My son and daughter stood frozen in the hallway.

My father looked up at them, forcing a grin like bravery was an obligation.

“See?” he said, trying to joke. “Still got it.”

But his hand trembled.

And in that moment, something in me snapped cleanly in half.

Not because he fell.

Because I realized how easily he could disappear.

How quickly “next month” becomes “never.”

How my mother’s light could one day glow for a person who isn’t coming anymore.

I helped him up slowly.

He leaned on me.

Just a little.

But the weight of it felt like a confession.

Later, when the adrenaline drained and the house returned to its quiet hum, my father sat in his recliner and stared at that porch light through the window.

“I used to keep that on when you were a teenager,” he said.

I frowned. “Why?”

He didn’t look at me.

“Because I wanted you to know,” he said, voice rough, “that no matter how far you ran, there was a place you could still come back to.”

My son heard him.

I saw it in the way his face changed. Like a door opened in his chest that he didn’t know existed.

And here is the hard, viral, comment-section truth I’m about to drop into your lap:

Most of us don’t abandon our parents because we hate them.

We abandon them because the world rewards abandonment.

The world rewards the job that takes you away.

The world rewards the promotion that steals your weekends.

The world rewards the hustle that makes you “important.”

The world claps when you move on.

No one claps when you drive three hours to sit on a scratchy couch and watch an old man breathe.

But that couch is where love lives.

So I’m doing something now that I never did before.

I’m saying it out loud, where it can’t be hidden behind good intentions:

I have been a thief.

And I’m trying to stop.

Not by posting about it.

Not by buying a better gift.

But by showing up again. And again. And again.

Even when it’s inconvenient.

Even when my kids complain.

Even when my calendar screams.

Even when my ego begs me to feel “productive.”

Because one day, productivity will not hold my hand.

One day, my inbox will not mourn.

One day, my mortgage will not stand at a grave and whisper, I wish I’d done more.

So here’s the question I want you to argue about in the comments, because I genuinely want to know where people land:

Do adult children owe their parents time… or is time a gift that can’t be demanded?

And here’s the question that scares me more:

If your parents’ porch light went dark tomorrow… what would you trade to see it glow one more time?

I know my answer.

I’d trade every “important” meeting.

Every “busy” excuse.

Every polished lie.

To hear my mother say, just once more:

“The light’s on, honey.”

And to be able to answer, finally—without multitasking, without delay, without stealing another breath from them:

“I’m home.”

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta