Skip to Part 2 👇👇⏬⏬

When the smartest kid in the senior class took a framing hammer and smashed his brand-new smartphone into a thousand shards of glass and plastic right on my workbench, I didn’t call the principal. I didn’t call his parents. And I certainly didn’t call security.

I walked over, swept the electronic debris into a trash can, locked the classroom door, and turned off the industrial lights.

“Good,” I said, my voice cutting through the stunned silence of twenty teenagers. “Now that the noise stops, the work begins.”

I’ve been teaching Shop Class at Oak Ridge High for thirty-five years. I have sawdust in my lungs, three missing fingertips, and a heart that beats to the rhythm of a table saw. I’ve watched America change from the vantage point of this dusty room. I’ve seen the boots get cleaner, the hands get softer, and the eyes get infinitely sadder.

Back in the nineties, kids came in here with grease under their nails, talking about engines and football. Now? They walk in like ghosts. Shoulders hunched, eyes glazed, thumbing glass screens as if their oxygen supply depends on the next notification. They are the most connected generation in human history, yet I have never seen a group of young people so profoundly, devastatingly alone.

This semester, the air in Room 104 felt heavy. It smelled worse than burnt transmission fluid; it smelled like panic. The news cycle outside these walls is a constant scream of division. I hear them whispering before class, repeating the angry headlines they see online. Us versus Them. The kids with the $80,000 electric trucks versus the kids on free lunch programs. The ones who shout versus the ones who hide.

And then there’s the administration.

They told me last Friday. This is the end. Next fall, Room 104 won’t be a woodshop. They are auctioning off the lathes, the drill presses, and the bandsaws. They are replacing my sturdy oak workbenches with plastic tables, 3D printers, and Virtual Reality headsets. They call it the “Future Ready Innovation Hub.”

I call it a tragedy. We are forgetting a simple truth: before you can code the world, you have to know how to build it. But I’m just an old man with a chisel in a digital age.

That Tuesday, the rain was relentless—a cold, gray downpour that seemed to seep right into the concrete foundation. The tension in the room was thick enough to choke on. You could feel the anxiety vibrating off these kids like heat off a radiator.

I looked at the curriculum. We were supposed to be making simple birdhouses. I looked at their faces. A birdhouse wasn’t going to fix this.

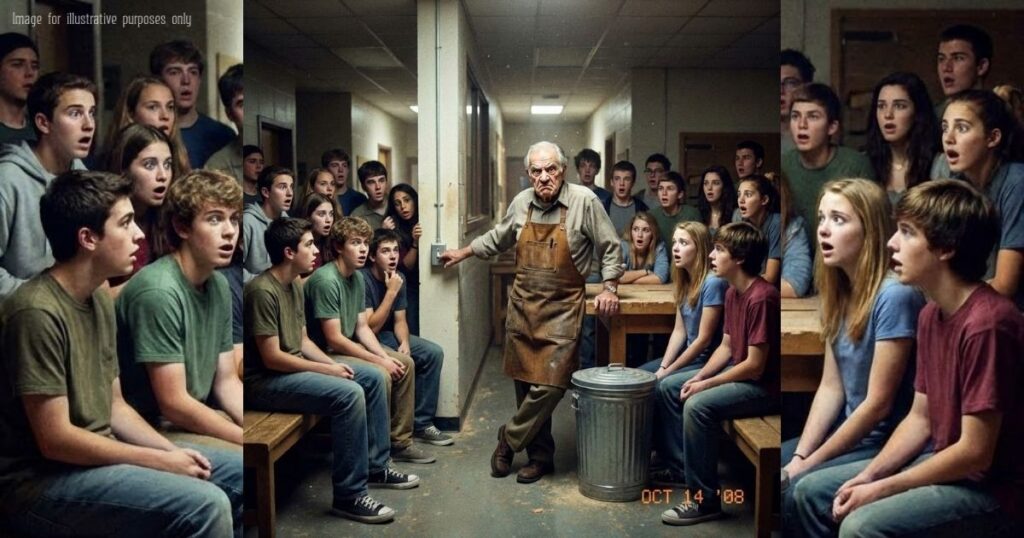

“Put the tools down,” I barked. My voice is like gravel, worn down by decades of shouting over planers. “Everyone. Sit on the benches. Now.”

They looked confused. A few rolled their eyes, but they hopped up, legs dangling.

I walked to the corner, to the “Burn Pile.” This was the scrap wood I kept for the incinerator. The ugly pieces. The knots, the warps, the twisted grain, the oak that was too hard, the pine that was too sappy.

I grabbed an armful of the ugliest, roughest blocks I could find. I walked down the line and dropped a piece of jagged wood in everyone’s lap.

“Look at it,” I said.

“It’s garbage, Mr. Russo,” a boy named Jason said. He was the star quarterback, but I saw his hands shaking. He was terrified of losing his scholarship, terrified of one bad injury ending his life’s plan.

“It’s not garbage,” I corrected. “It’s honest. Run your hand over it.”

They did. A few flinched as splinters caught their skin.

“Rough, right? It snags. It cuts. It’s uncomfortable.” I leaned against my desk, crossing my arms over my shop apron. “That piece of wood is exactly how you feel right now. I see it. I see the stress. I see the anger you’re carrying because your dad lost his job at the plant. I see the fear that you’re not smart enough, or thin enough, or rich enough for the algorithm.”

The room went dead silent. Even the hum of the ventilation system seemed to fade.

“In that digital world you live in,” I pointed to the trash can where the smashed phone lay, “when you don’t like something, you block it. You swipe left. You filter it out. You use an app to smooth your skin and whiten your teeth. You pretend the flaws aren’t there. But in here? In the real world? You can’t swipe away a splinter. You have to deal with it.”

I went to the cabinet and pulled out the sandpaper. Not the fine stuff. The 60-grit. The coarse, angry red paper that feels like rocks glued to a sheet. I tore it into squares and passed it out.

“No power sanders today,” I announced. “Just you, your hands, and that ugly block of wood. I want you to sand it until it’s smooth. Every time you push, I want you to think about one thing that’s making you heavy. Every stroke is a fight. If you’re angry, put it into the wood. If you’re scared, put it into the wood.”

“This is gonna take forever,” a girl named Sarah whispered. She was the one who always wore long sleeves, even in June, to hide the scars on her arms.

“Then you better get started,” I said softly.

At first, the sound was tentative. A slow scritch-scratch. They were bored. They were skeptical. They looked at me like I was a senile dinosaur clinging to the past.

But then, the rhythm took over.

There is something primal about manual labor. It bypasses the intellectual brain and talks directly to the nervous system. The sound grew louder. Scritch-scratch. Scritch-scratch. It became a drone, a collective heartbeat filling the room.

I watched Jason. He wasn’t just sanding; he was attacking the wood. His jaw was clenched tight. I knew his family was losing their home to the bank. I knew he felt helpless. Now, he had something he could control. He could force his will upon this object. He could change reality with his own sweat.

I watched Sarah. She was crying silently, tears dripping onto the jagged oak, darkening the grain. But she didn’t stop. Her arm moved back and forth, a hypnotic motion. She was grinding down the sharp edges of the wood, and maybe, just maybe, grinding down the sharp edges of her own thoughts.

Forty minutes passed. The air filled with the smell of oak dust—a dry, earthy, sweet scent that I will miss until the day I die. Sweat was beading on their foreheads. They weren’t looking at each other’s clothes or wondering who liked whose post. They were all covered in the same fine, beige dust. They looked like a team. They looked human.

The boy who smashed the phone—Liam—was breathing hard. His knuckles were white. He stopped, panting, and ran his thumb over the surface.

I walked over to him. “How is it?”

He didn’t look up. “It’s… hot.”

“Friction creates heat,” I said quietly, loud enough for the room to hear. “And heat changes things. It burns away the impurities.”

I reached into my apron and pulled out a tin of beeswax and orange oil—my own mixture. I opened it and scooped out a dollop with an old rag.

“You’ve done the hard work,” I addressed the class. “You took the roughness away. You faced the ugly parts. Now, look what happens when you treat it with care.”

I handed the rag to Liam. “Rub it in. Circular motions. Don’t be afraid to get your hands dirty.”

He hesitated, then applied the wax.

The transformation was instant.

The dull, dusty gray wood exploded into a rich, deep amber. The twisted grain that looked so ugly and unusable before now shimmered with complex beauty. The knots looked like character marks, not flaws. The scars in the wood caught the light and turned it into gold.

“Whoa,” Liam whispered. The anger in his eyes was gone, replaced by awe.

I looked at the class. Twenty faces, covered in dust, looking at twenty pieces of beautiful wood.

“We spend so much time trying to be perfect,” I said, my voice thick with emotion. “We try to present a polished image to the world before we’ve done the work. We want the shine without the friction. But life doesn’t work that way.”

I walked to the front of the room. “You are not defined by the roughness you start with. You are not defined by your trauma, or your bank account, or your mistakes. You are defined by how hard you are willing to work to smooth it out.”

I pointed to the blocks in their hands. “That beauty? It was always there. It was hiding under the rough surface. You just had to grind through the hard stuff to find it.”

For the last ten minutes of class, nobody spoke. They were too busy waxing their blocks, marveling at the hidden colors they had revealed. When the bell rang—the loud, jarring electric buzzer that signals the end of the period—nobody rushed to the door.

They wiped their hands slowly.

As they filed out, the atmosphere had shifted. The heaviness had lifted, replaced by a tired but genuine lightness. They weren’t checking their pockets for phones.

Liam stopped at my desk. He held his block of wood like it was a gold bar. It was smooth as glass, smelling of honey and earth.

“Can I keep this?” he asked.

“You earned it,” I said. “It’s yours. Take it with you.”

He looked at me, right in the eyes—something he hadn’t done all year. “Thanks, Coach.”

I watched him walk out into the hallway, into the noise and the chaos of the modern world. He walked past the flickering screens in the hallway. He had his hand in his pocket, clutching that piece of wood. A tactile anchor. A reminder that he could change things with his own two hands.

Next year, this room will be full of plastic filaments and blinking lights. They say that’s the future. They say we need to prepare you for the digital economy. Maybe they’re right. I’m just an old man who likes the smell of sawdust.

But I know this: You cannot download resilience. You cannot 3D print character. An app cannot teach you how to survive a storm.

Sometimes, the only way to heal a fracture in the soul is to get your hands dirty, feel the friction, and sand it down until the true grain reveals itself.

That is the one lesson I hope they pack in their luggage when they leave this place. We are not machines to be programmed. We are wood to be worked. And the most beautiful grain is always found in the trees that withstood the strongest storms.

PART 2 — The Day the Sandpaper Video Escaped Room 104

By Wednesday morning, my classroom door wouldn’t shut all the way.

Not because the hinges were warped—those old steel hinges have survived three decades of teenagers slamming them in anger. It wouldn’t shut because there were bodies in the way.

A line of kids stood outside Room 104 like it was a concert and I was selling tickets. Some of them I recognized—my third-period crew, still smelling faintly of beeswax and oak dust. Some of them I didn’t. Sophomores. Juniors. A girl from the honors hallway with a backpack that probably cost more than my first truck. A kid in a hoodie who usually vanished into the bathroom between bells.

They weren’t talking much. They were just… waiting.

I pushed through them with my coffee in one hand and my keys in the other, and they parted like I had gravity.

A boy I didn’t know held out something in his palm like an offering.

It was a block of wood.

Not just any block. I recognized the twisted grain and the knot that looked like an eye. It was one of my ugly pieces, sanded smooth and waxed until it glowed like amber.

“Where’d you get that?” I asked.

He swallowed. “My cousin. He’s in your class.”

“Why are you here?”

The kid looked down at the wood, then back at me. His eyes were bloodshot. “Because… I didn’t know you could make something ugly look like that.”

Behind him, the honors girl lifted her sleeve and showed a raw, red welt across her knuckle.

“Sixty-grit,” she said quietly. “I tried it at home. It hurts.”

I opened the door all the way and let the smell of sawdust roll out into the hallway like a confession.

“Get in,” I said. “Before someone from upstairs sees this and has a heart attack.”

They filed in—too many for the room, too many for the rules, too many for the clean, laminated future they’d been selling us.

And that’s when I saw what was happening.

Two kids at the back—Jason’s teammate and a girl from Sarah’s math class—were holding a phone between them, angled like they were watching a replay.

But it wasn’t a football clip.

It was my classroom.

The video was shaky and grainy, taken from someone’s lap like a secret. It showed Liam rubbing beeswax into that rough block of oak. It showed the transformation—gray to gold, dead to alive. It showed twenty teenagers sitting in silence, their faces soft and human instead of armored.

Someone had added words over the footage in big white letters:

YOU CAN’T SWIPE AWAY A SPLINTER.

Under that, a caption:

THIS OLD TEACHER DID ONE THING, AND THE WHOLE CLASS CHANGED.

I didn’t feel pride. Pride is for trophies.

What I felt was something colder.

Exposure.

Because when a moment escapes the room and hits the outside world, it doesn’t stay pure. It gets grabbed. It gets twisted. It gets used as a weapon.

I set my coffee down and stared at the screen.

“How many people have seen that?” I asked.

Jason didn’t answer. He looked like a man waiting for a sentence.

Liam—standing by my workbench, hands shoved deep into his pockets—finally spoke.

“Millions,” he said.

I blinked once. “That’s not funny.”

“It’s not a joke, Coach.” He lifted his chin toward the window. “Look.”

I walked to the glass and peered out.

Two news vans were parked in the student lot.

Not real ones with logos—because we don’t say names in this room—but the kind with antennas and people holding microphones, hungry for a story.

My stomach did that old sinking thing it hasn’t done since I got called into the principal’s office in 1996 for letting a kid cry in my classroom instead of sending him to detention.

I turned back to the kids.

“Who posted it?” I asked.

Nobody moved.

Which told me everything.

It wasn’t one person. It was all of them.

A collective decision.

A rebellion made of silence and sandpaper.

Before I could say another word, the intercom crackled above the door.

“Mr. Russo.” The principal’s voice—tight, practiced. “Please come to the main office immediately.”

Twenty sets of eyes locked onto mine.

Sarah’s eyes were the worst. She looked like someone who had finally found a place to breathe—and now someone was closing the door.

I lifted my chin and forced my voice into something steady.

“Keep the door locked,” I told them. “Don’t touch the machines. Don’t post anything else. And for the love of God, if anyone asks you questions, you tell them this is Shop Class, not a circus.”

Jason raised a trembling hand. “Are you in trouble?”

I paused at the threshold.

“Kid,” I said, “I’ve been in trouble since the day I started caring.”

The main office smelled like lemon cleaner and fear.

The kind of fear that wears a tie.

The principal sat behind her desk with two people I hadn’t seen before—one from the district, one from the legal department, both with smiles that didn’t reach their eyes.

A tablet sat on the desk, playing the video on a loop.

The district man spoke first. “Mr. Russo, do you understand the situation?”

I looked at him. His hands were smooth. No calluses. No scars. A man who’d never sanded anything in his life.

“I understand you’re worried about a video,” I said.

He smiled, like I’d confirmed his diagnosis.

“We’re worried about liability,” he corrected. “We’re worried about unauthorized recording of minors. We’re worried about you encouraging property destruction. We’re worried about the message.”

“The message?” I repeated.

The legal woman leaned forward. “The internet is dividing into sides, Mr. Russo. Some people are praising you. Others are accusing you of—” she glanced down at notes, “—shaming technology, promoting outdated trades, and emotional manipulation.”

“Emotional manipulation,” I said slowly, tasting the words like sawdust. “In a room full of kids who look like they haven’t slept in a year.”

The principal cleared her throat. “Frank… we’re getting calls. Parents. Alumni. Reporters. The superintendent. They want a statement.”

“A statement,” I echoed.

The district man tapped the screen. “This line—‘You can’t swipe away a splinter.’ It’s being used as an argument in broader debates about education, mental health, and youth culture. It’s stirring people up.”

He said stirring people up like it was a disease.

I leaned back in the chair and looked him dead in the eye.

“Maybe people need stirring,” I said.

His smile tightened. “We need you to be careful. You’re a respected employee. But you are not authorized to run… therapy sessions.”

“It wasn’t therapy.” My voice came out rough. “It was sanding wood.”

The legal woman didn’t blink. “A student destroyed an expensive device in your classroom. You did not report it.”

I held her gaze. “He destroyed his own device.”

“That’s not the point.”

“No.” I nodded slowly. “That’s exactly the point. In this building, when a kid breaks down, everyone wants to know who to blame. Me. The parents. The phones. The news. The other kids. The politics outside. Somebody to point at.”

I leaned forward until my elbows touched the desk.

“But in my room, we don’t point. We build.”

The principal’s eyes softened for half a second—then hardened again, like she’d remembered her job.

“We’re putting you on administrative leave for the rest of the week,” she said, voice low. “Not as punishment. As protection.”

“Protection from who?” I asked.

Her eyes flicked toward the window, where I could see the front steps crowded with cameras and curious teenagers.

“From the story,” she whispered.

I stood up.

“Let me tell you something about stories,” I said. “You don’t control them once they leave the room. But you can choose whether you tell the truth in them.”

The district man opened his mouth.

I held up a hand.

“I’m going back to my classroom,” I said.

“You can’t,” the legal woman snapped, the first crack in her polish.

I shrugged. “Then you better call security. Because I’m done watching adults protect their reputations while kids drown quietly.”

I walked out.

And for the first time in thirty-five years, the lemon-cleaner office didn’t scare me.

By the time I got back to Room 104, the hallway looked like a parade.

Students pressed against lockers, craning their necks. Teachers stood with crossed arms, pretending they weren’t watching. Someone had printed screenshots of the video and taped them to the bulletin board like protest posters.

YOU CAN’T DOWNLOAD RESILIENCE.

My own words, turned into slogans.

That’s when I understood the danger.

A slogan is sharp. It cuts fast. It makes people choose sides.

And the thing these kids needed most was the opposite of sides.

They needed a place where they could be whole.

I pushed into my classroom.

The kids were exactly where I’d left them—sitting on benches, hands on their sanded blocks like they were holding warm stones.

Nobody was on a phone.

Liam stepped toward me. “They’re saying you’re suspended.”

“I’ve been called worse,” I said.

Jason stood up too, big frame shaking like a leaf. “My mom thinks you’re… like, brainwashing us. She says you’re against the future.”

A few kids laughed nervously.

Sarah didn’t laugh.

She just stared at me like she was waiting to see if I’d abandon them.

I took a breath.

“Listen to me,” I said. “The future is not the enemy. Screens aren’t demons. Tech isn’t evil. But if the only thing we teach you is how to live inside glass… then the first time life gets rough, you’ll shatter.”

Silence.

A kid in the back—the hoodie kid—spoke without raising his head.

“My dad says trades are for kids who can’t make it,” he muttered.

That line hit the room like a thrown wrench.

Jason flinched. The honors girl stiffened. Liam’s jaw tightened.

This was the controversial heart of it, right here. The thing nobody says out loud in polite classrooms.

The hierarchy.

The invisible caste system built on SAT scores and college banners and who gets praised at awards night.

I walked to the burn pile and grabbed a fresh piece of scrap—ugly, splintered, honest.

I held it up.

“You see this?” I asked. “This is what people call ‘less than.’”

I handed it to the hoodie kid.

He took it like it might bite.

“Your dad might be a good man,” I said, “but he’s repeating a lie our culture loves because it makes certain people feel safe.”

I looked around at them.

“Here’s the truth that makes adults uncomfortable,” I said. “A society can survive without influencers. It cannot survive without builders. Without fixers. Without people who know how to make water flow, lights turn on, roofs hold, and shelves stand.”

I tapped my chest.

“And here’s another truth that makes kids uncomfortable. You can be brilliant and still be helpless. You can get straight A’s and still fall apart when life doesn’t give you a rubric.”

The honors girl swallowed. Her knuckles were still raw.

Sarah’s eyes glistened.

Liam whispered, “So what do we do?”

I stared at the empty space where the old lathe sat.

Next fall, that space would be plastic tables and blinking headsets.

They were going to erase the one place in the building where friction was allowed.

I felt anger rise—hot and clean.

Then I remembered what I’d told them.

Friction creates heat.

Heat changes things.

“Today,” I said, “we build something the whole school can’t ignore.”

Jason frowned. “Like what?”

I turned to the far wall—the cinderblock wall that had been bare for years except for a faded safety poster and a crooked clock.

“We’re going to make a wall,” I said.

“A wall?” Liam repeated.

“Not a wall to keep people out,” I corrected. “A wall to show people what’s inside.”

I grabbed a box of nails and a pile of thin scrap boards.

“We’re building a display. Every one of you takes your finished block. On the rough side—the side you didn’t sand—you write one sentence. One honest sentence about what you’re carrying.”

Sarah’s breath caught.

I didn’t look at her directly. I didn’t need to. I could feel her fear like static.

“No names,” I added. “No drama for likes. Just truth.”

Jason shifted. “Like… ‘I’m scared to get injured’?”

“Exactly.”

Liam’s voice was small. “What if it’s… worse than that?”

I met his eyes. “Then it’s even more important.”

The room went still.

Then, slowly, kids started reaching for pencils.

The sound of graphite on rough wood is one of the most human sounds I know. It’s not digital. It doesn’t disappear.

It leaves a mark.

I moved through the room without reading. That wasn’t my right.

But sometimes you don’t have to read to feel the weight.

A kid’s hand shaking as he writes.

A girl pressing too hard, like she’s trying to carve the words into existence.

Jason wiped his face with his sleeve and stared at his block like it was a confession booth.

Sarah held her pencil above the wood for a long time, frozen.

I crouched beside her bench.

“You don’t have to write what you’re not ready to share,” I murmured.

Her lips trembled. “If I don’t write it, it wins.”

That sentence broke something in me.

Not loudly. Not theatrically.

Quietly. Like a seam giving way.

She wrote.

Her hand didn’t stop shaking, but she wrote anyway.

And that, right there, was the lesson.

Not sanding.

Not wax.

Courage.

By lunchtime, we had the frame built—two-by-fours screwed into studs, strong enough to hold a hundred blocks.

Kids came in waves.

Not just my class anymore.

Word spread fast, the way wildfire spreads when the air is dry.

They’d seen the video. They’d heard the rumors. They were hungry for something that felt real.

Some wrote sentences and left without speaking.

Some stayed to help hammer.

Teachers wandered in and out, pretending to check on safety while their eyes kept drifting to the blocks already mounted.

A counselor came in and stood silently for five full minutes, reading the rough-side sentences, her hand over her mouth like she was trying not to cry in front of teenagers.

I didn’t stop her.

Let them see adults feel.

Let them see it’s allowed.

By the end of the day, the wall was half full.

A mosaic of polished wood facing outward—beautiful, glowing, smooth.

And if you looked closely, you could see the rough side behind it, where the sentences lived.

Some of the sentences were small.

I MISS MY GRANDPA.

I’M TIRED OF PRETENDING I’M OKAY.

I FEEL LIKE I’M ALWAYS BEHIND.

Some were blunt.

MY HOUSE IS GETTING TAKEN.

I CAN’T STOP COMPARING MYSELF.

I’M AFRAID I’LL DISAPPOINT EVERYONE.

And some—some were the kind of honest that makes adults panic because it refuses to be neat.

I DON’T WANT TO BE HERE SOMETIMES.

No details. No instructions. No spectacle.

Just a sentence, hanging in the air like a flare.

I felt my throat tighten.

This is why people wanted a statement.

This is why they wanted to shut it down.

Because you can’t sell “Future Ready” when the future is made of kids quietly begging to be seen.

At the final bell, the principal appeared in the doorway, her face pale.

She looked at the wall.

Then she looked at me.

“Frank,” she said softly. “What did you do?”

I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t accuse her. I didn’t even blame the district.

I just gestured toward the blocks.

“I gave them friction,” I said. “And for the first time in a long time, they felt something real.”

Her eyes glistened, and for one second, she wasn’t an administrator. She was a person.

Then her phone buzzed—her own screen lighting up with the next emergency.

She swallowed hard. “The superintendent is calling an emergency board meeting tonight.”

“Good,” I said.

Her eyebrows lifted. “You want to go?”

“I want them to see this wall,” I replied. “Not the video. Not the slogans. This.”

She hesitated. “They’re saying you sparked a controversy.”

I nodded. “Then maybe we finally found the nerve.”

That night, the board room was packed.

Parents in work boots sat next to parents in blazers.

Kids sat behind them, unusually quiet, like they understood this wasn’t about grades anymore.

The superintendent sat at the front with the district man and the legal woman, all of them wearing faces that said: We will handle this.

They called my name.

I walked to the microphone with a cardboard box in my arms.

Inside the box were twenty sanded blocks of wood.

Not the display ones. These were the ones my class had started with—ugly, warped, rough.

I set the box down on the table in front of them.

The superintendent cleared her throat. “Mr. Russo, we appreciate your years of service. However, we must address—”

I held up a hand.

I didn’t do it with disrespect.

I did it with exhaustion.

“Before you address anything,” I said, “I want you to do one thing.”

I reached into the box and pulled out a block.

“Run your hand over that,” I said, holding it out.

A ripple of discomfort moved through the front row.

The superintendent looked like I’d asked her to lick the floor.

But a board member—a woman with silver hair and a tired face—reached out and touched the wood.

She flinched when a splinter snagged her skin.

Her eyes widened.

“Rough,” she murmured.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “Now imagine you’re sixteen and your whole life feels like that inside.”

The room fell silent.

I pulled out another block, this one sanded and waxed, glowing under fluorescent lights.

“And now,” I continued, “imagine someone gives you the tools to change it. Not with an app. Not with a filter. With work. With friction. With your own hands.”

A parent in the audience stood up, voice sharp. “So you’re saying technology is the problem?”

I shook my head. “No.”

Another parent shouted, “My kid needs coding to survive! Not woodshop!”

I nodded again. “Yes.”

Then I let the quiet settle.

“You see what’s happening?” I said. “This is what the internet did to us. It trained us to pick a side. Tech or trades. College or work. Screens or sanity.”

I leaned into the microphone.

“But the truth is boring and complicated, and that’s why it doesn’t go viral.”

A few kids snorted at that, despite themselves.

“The truth,” I said, “is that your kids need both.”

I gestured to the box.

“They need to learn how to build a future. And they need to learn how to survive their own minds while doing it.”

I reached into my coat pocket and pulled out a folded sheet of paper.

It was a list.

Not names. Not accusations.

Just sentences.

I didn’t say where they came from. I didn’t point to Sarah. I didn’t expose anyone.

I just read them slowly, without drama, like scripture.

“‘I feel invisible even when I’m surrounded.’”

“‘I don’t know how to talk to my parents without fighting.’”

“‘I’m scared of failing because everyone thinks I’m the smart one.’”

“‘I’m scared of succeeding because then I’ll have to leave my little brother behind.’”

You could hear parents breathing.

“Now,” I said, folding the paper, “you can shut down my shop. You can fill that room with plastic tables and shiny headsets. You can call it progress.”

I paused, letting my gaze sweep the room.

“But you cannot pretend those sentences disappear.”

I pointed at the board.

“If you want to be ‘future ready,’ then get ready for this: a generation that can code circles around you but doesn’t know how to sit with discomfort without breaking something. A generation that can build apps but can’t build themselves back after disappointment.”

The superintendent’s face tightened. “Mr. Russo, we have counselors. We have programs—”

“You have programs,” I interrupted, voice still controlled, “but you don’t have places.”

I tapped the box.

“You don’t have a room where kids can be imperfect and still be useful. A room where mistakes become sawdust instead of shame.”

The silver-haired board member looked down at the block she’d touched. Her fingertip had a tiny bead of blood from the splinter.

Nothing dramatic.

Just proof.

She whispered, almost to herself, “So what are you asking?”

I didn’t ask for my job back. I didn’t beg.

I asked for the kids.

“I’m asking you not to replace the last room in this building that teaches friction,” I said. “Keep the innovation hub if you want. Add the printers. Add the headsets.”

A few tech-minded parents nodded, relieved.

“But don’t tear out the workbenches,” I finished. “Don’t auction off the lathes. Don’t turn every problem into something you can ‘solve’ without touching it.”

I lifted the waxed block one last time.

“Because some problems aren’t solved,” I said. “They’re sanded. Slowly. Painfully. By hand.”

The room didn’t clap right away.

It just breathed.

And in that long, heavy silence, I realized something that made my chest ache:

The viral video wasn’t what scared the adults.

What scared them was the possibility that the kids were right.

That the reason they were so anxious, so angry, so exhausted… wasn’t because they were weak.

It was because we built a world that’s smooth on the surface and razor-sharp underneath.

And we told them to smile for the camera while it cuts them.

After the meeting, as people spilled into the hallway—arguing quietly, hugging awkwardly, avoiding eye contact—Sarah approached me.

She didn’t have her hood up tonight.

She looked smaller without it.

“I think they’re going to keep part of the shop,” she whispered.

“Maybe,” I said.

She held out her block.

On the smooth side, it glowed like honey.

On the rough side, she’d written her sentence.

I didn’t read it.

I didn’t need to.

Her eyes were clearer than I’d ever seen them.

“Coach,” she said, voice shaking, “people online are fighting about you.”

“I know,” I sighed.

She swallowed. “They’re calling you a hero or a monster.”

I barked out a short laugh. “That’s the internet for you. It can’t handle an ordinary man doing one decent thing.”

She nodded slowly. “But… they’re also talking about us.”

“Good,” I said. “Let them talk.”

She frowned. “Isn’t that bad?”

I shook my head.

“Talking isn’t the enemy,” I said. “Silence is.”

I looked down the hallway at the adults, at the kids, at the world made of screens and opinions and fast judgments.

Then I looked back at her.

“Here’s what I want you to remember,” I told her. “They can argue all they want about me. About tech. About trades. About the future.”

I tapped her block gently.

“But nobody gets to argue about your truth.”

Sarah’s lip quivered.

Then she nodded once—firm, like she’d driven a nail straight.

She turned and walked away into the crowd, her block of wood clutched against her chest like armor.

And for the first time in a long time, I felt something I didn’t expect.

Not victory.

Not relief.

Hope—rough, unfinished, still full of splinters.

The kind you have to sand into shape.

The next morning, the wall in Room 104 was full.

Polished faces outward.

Rough truths hidden behind.

A hundred blocks.

A hundred quiet battles.

And taped beneath it, someone had added a new line in messy marker:

IF THIS WAS YOUR KID, WHAT WOULD YOU WANT THEM TO LEARN—HOW TO GO VIRAL, OR HOW TO SURVIVE?

That question will make people angry.

It will make them comment.

It will make them choose sides.

But if it also makes one parent put their phone down long enough to look at their teenager… then maybe the controversy was worth it.

Because the truth is this:

You can teach a kid to build a résumé.

But if you never teach them to build resilience, you’re just handing them a polished life that will crack the first time it gets real.

And real always comes.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta