I hid a secret in my bottom desk drawer for 15 years. When the principal called me in, I thought I was losing my pension.

“Mrs. Miller, close the door,” she said.

My heart hammered against my ribs. I’ve been teaching 8th grade history in this district for three decades. I know the rules. I know the red tape.

And I knew I had broken about a dozen protocols with what was inside my bottom drawer.

It started ten years ago during a brutal Midwest winter.

A girl named Sarah sat in the back row. She was brilliant but silent. One day, during a pop quiz, I saw her hands shaking. They were bright red, chapped to the point of bleeding.

She wasn’t wearing a coat. She never wore a coat.

I didn’t fill out a referral form. I didn’t call a social worker to start an investigation that would take weeks.

I went to the discount store on my lunch break. I bought a pair of thermal gloves, thick wool socks, and a heavy scarf.

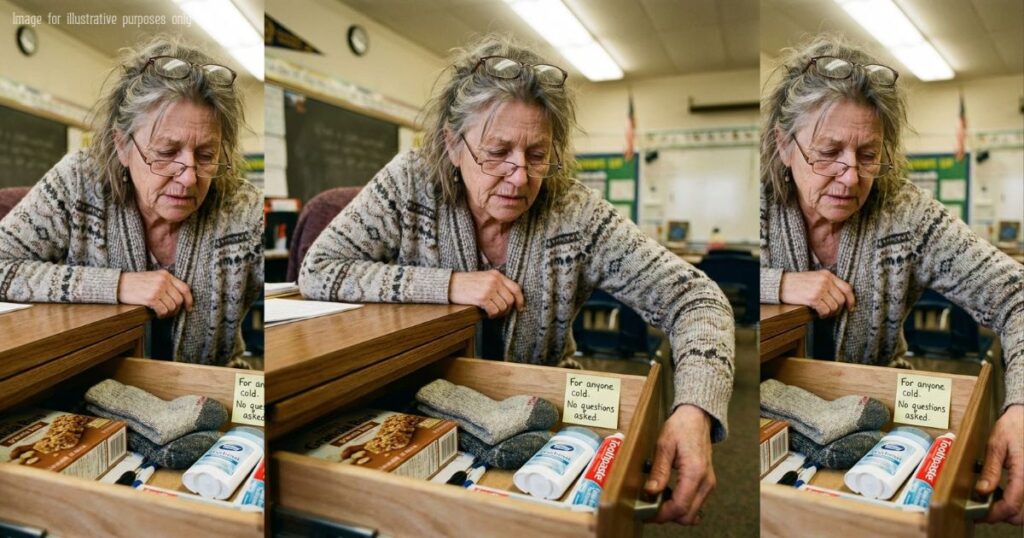

I put them in the bottom drawer of my desk. I placed a sticky note on top: “For anyone cold. No questions asked.”

By 3:00 PM, the drawer was empty.

The next day, there was a granola bar inside.

That was the birth of “The Drawer.”

Over the years, it became the worst-kept secret in the school.

It wasn’t for pencils or staplers.

It was for the things we aren’t supposed to talk about in a country this wealthy.

It held deodorant for the boy who was getting bullied in the locker room because the water was shut off at home.

It held feminine hygiene products for the girls who were using rough paper towels from the bathroom because their moms couldn’t afford the pink tax.

It held peanut butter crackers for the kids whose “dinner” was the school lunch they ate at 11:30 AM.

I never saw who took what. That was the rule.

If the drawer was open, my back was turned.

Then came Marcus.

Marcus was the kid other teachers warned you about in the break room. “Defiant.” “Unreachable.” He wore the same hoodie every day, hood up, eyes down.

Last Tuesday, he stayed after the bell rang.

He stood by my desk, aggressively tapping his foot. He looked angry, but I’ve been doing this long enough to know that anger is usually just a bodyguard for sadness.

“Is it true?” he mumbled, looking at the floor.

“Is what true, Marcus?”

“The drawer. Is it… for everyone?”

“It’s for anyone who needs it.”

He didn’t move for a long time. Then, quick as lightning, he yanked the drawer open.

He grabbed a tube of toothpaste, a pair of fresh socks, and three protein bars.

He slammed it shut and ran out the door before I could breathe.

The next morning, I arrived early to grade papers.

The drawer was slightly open.

Inside, sitting on top of the generic fruit snacks, was a folded winter hat. It wasn’t new. It was a little pilled, gray and worn.

Underneath it was a crumpled piece of loose-leaf paper.

“My pop says you can’t take without giving. It’s my brother’s old hat. It’s warm. Thanks for the food.”

I sat there and cried into my coffee.

Which brings me back to the principal’s office this morning.

I was ready to defend myself. I was ready to argue that hungry kids can’t learn about the Constitution.

The principal slid a piece of paper across the desk.

It wasn’t a disciplinary notice. It was an email from a parent. Marcus’s dad.

It read:

“I work two jobs. I try my best. But lately, we’ve been choosing between lights and laundry detergent. My son came home smiling yesterday for the first time in months. He said, ‘Dad, Mrs. Miller doesn’t look down on us. She just helps.’ Thank you for making my son feel like a human being.”

The principal looked at me, her eyes wet.

“We can’t officially fund this, Mrs. Miller,” she whispered.

Then she reached into her purse, pulled out a twenty-dollar bill, and slid it across the desk.

“But I noticed you’re low on shampoo.”

We live in a world where everyone is screaming on the internet. Everyone is fighting about policies and politics. Everyone wants to be right.

But in my classroom, nobody cares who is right.

They just care that someone noticed they were hungry.

They just care that they aren’t alone.

Tonight, check on your neighbors. Check on the quiet kid.

Because sometimes, the only thing separating a child from despair is a bottom drawer and a person who gives a damn.

PART 2 — The Day the Drawer Went Public

If you read Part 1, you know what “The Drawer” was: my bottom desk drawer turned into an unofficial lifeline—gloves, socks, toothpaste, pads, crackers—no questions asked.

You also know how it ended.

Me in the principal’s office, heart in my throat, sure I was about to lose the pension I’d spent thirty years earning… only to watch her slide a twenty-dollar bill across her desk like it was contraband.

“But I noticed you’re low on shampoo,” she whispered.

I walked back to my classroom with that bill folded in my pocket like a match.

Not because it was twenty dollars.

Because it was permission.

Not official permission—nothing with a signature, nothing you could file away—but the kind that matters more. The kind that says: I see what you see. I’m not pretending anymore.

The hallway smelled like floor wax and old paper. Kids were already pouring in for first period, loud and half-awake, carrying backpacks that looked heavier than their bodies.

I unlocked my classroom door.

And froze.

My desk chair was pulled out.

Not dramatically. Just… an inch too far. Like someone had sat there and changed their mind.

The drawer was closed, like always.

But on top of my desk—right where I grade essays and scribble lesson plans—sat a single sheet of printer paper.

No letterhead.

No signature.

Just one sentence, typed in a plain font:

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT YOUR DRAWER.

My mouth went dry.

For a ridiculous second, my brain tried to bargain.

Maybe it’s a student prank.

Maybe it’s about an actual drawer. Like… a broken drawer.

But my hands were already shaking when I flipped the page over.

On the back was another sentence.

COME TO THE FRONT OFFICE DURING YOUR PLANNING PERIOD.

No name.

No “please.”

No warmth.

Just a summons.

And that’s the thing about working in a school long enough—you learn what different kinds of paper feel like in your bones.

Some paper is celebration.

Some paper is paperwork.

And some paper is a trap.

By 9:42 a.m., I had taught the causes of the Civil War while barely hearing my own voice.

My eyes kept flicking to my desk.

To the drawer that had been my quiet rebellion for a decade.

To the place where my kindness lived… and where my career could die.

When the bell finally rang for my planning period, I walked down the hall like I was heading to an execution.

The front office was too bright, too clean, too quiet. A fish tank bubbled in the corner like nothing in the world had ever gone wrong.

The principal wasn’t at her desk.

Instead, sitting in one of the plastic chairs meant for parents in crisis, was a man I’d never seen before.

He stood when he saw me.

Tall. Crisp button-down. The kind of person who always looks like he has a meeting somewhere more important.

He offered his hand like a formality.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said. “I’m Mr. Lang. District compliance.”

The word compliance hit like a slap.

I shook his hand anyway. Because I was raised to be polite even when someone’s holding a knife behind their back.

He gestured toward a small conference room.

“Please.”

Inside, the air was cold. The chairs were stiff. There was a pitcher of water on the table that nobody was going to touch.

Mr. Lang sat across from me, opened a thin folder, and smiled like he practiced in a mirror.

“I want to be clear,” he began, “this is not a disciplinary meeting.”

My lungs didn’t believe him.

“This is a fact-finding conversation.”

That phrase—fact-finding—is what people say when they’re about to gather enough facts to bury you.

He slid a printed photo across the table.

It took my eyes a second to understand what I was looking at.

A picture of my desk.

My drawer open.

My sticky note visible:

FOR ANYONE COLD. NO QUESTIONS ASKED.

Under it, the outline of supplies.

Someone had taken the photo from the side, like they didn’t want to be seen.

I stared at it until the edges blurred.

“Do you recognize this?” he asked.

It was a stupid question.

“Yes,” I said.

“Is it your classroom?”

“Yes.”

“Is that your handwriting?”

“Yes.”

Mr. Lang nodded slowly, like he was checking boxes.

“Mrs. Miller, I’m going to ask you something, and I need an honest answer.”

I swallowed.

“How long has this been happening?”

My mind flashed back—Sarah’s red hands. The brutal winter. The first empty drawer. The first granola bar left behind like a thank you nobody dared say out loud.

I could lie.

I could pretend it started yesterday.

But there’s a strange thing about doing something quietly good for ten years—you stop thinking of it as bravery.

It just becomes… truth.

“About ten years,” I said.

His eyebrows lifted. Not in surprise. In concern.

“That’s… a significant amount of time.”

He leaned forward.

“Mrs. Miller, do you understand the liability issues involved here?”

“Liability,” I repeated, tasting the word like rust.

“Yes,” he said, and his voice turned instructional, like he was giving a presentation. “Food distribution. Allergens. Hygiene products. Medications—”

“No medications,” I cut in, too fast. “Never.”

He paused, like he’d noted my interruption.

“And you’ve never tracked what students take?”

“No.”

“No records.”

“No.”

“No parent consent.”

My cheeks burned.

“No,” I said again, quieter.

He sat back, steepled his fingers.

“Mrs. Miller… why didn’t you report these needs through official channels?”

I stared at him.

Because official channels are slow.

Because official channels ask poor kids to confess their poverty into a form.

Because official channels turn need into a case number.

Because some kids would rather freeze than be labeled.

But I didn’t say any of that yet.

I said the simplest truth.

“Because they were cold,” I whispered. “And hungry.”

Something flickered in his face—almost human.

Almost.

Then it disappeared under professionalism.

“I understand your intent,” he said, like intent was a candle and my career was gasoline. “But intent doesn’t erase protocol.”

He slid another paper across the table.

This one wasn’t a photo.

It was a printed email.

I recognized the format immediately. The way the lines lined up. The way the sender’s name sat at the top.

A parent.

I scanned it.

And my stomach dropped.

It wasn’t Marcus’s dad.

It was someone else.

And it wasn’t grateful.

It said:

I don’t send my child to school to learn how to take handouts.

If kids need things, their parents should provide them.

This encourages dependency and makes the classroom unsafe.

Also, what else is she “secretly” giving them?

I want this stopped immediately.

My throat tightened.

There it was.

The ugly idea people love because it makes them feel safe:

If someone is struggling, it must be their fault.

Mr. Lang watched my face like he was studying weather.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said gently, “this email triggered a formal review.”

I gripped the edge of the table.

“So what happens now?”

He inhaled, like he hated this part.

“Now, we have to determine whether district policy was violated.”

“And if it was?”

His eyes met mine.

“Then we have to determine consequences.”

Consequences.

Such a clean word for something that can ruin a life.

I thought of my mortgage.

My retirement.

The fact that my knees already ached walking the stairs.

I thought of the drawer, empty by 3:00 p.m. like clockwork.

And I did something I hadn’t planned to do.

I leaned forward.

“If you shut it down,” I said, voice low, “what happens to the kids?”

Mr. Lang hesitated.

“That’s not the scope of this meeting.”

“No,” I said, and now my voice shook with something sharper than fear. “It’s the scope of my job.”

His jaw tightened.

“Mrs. Miller, this district offers resources—”

“Resources that take weeks,” I snapped. “Resources that require paperwork. Resources that require a parent who answers calls and has transportation and doesn’t disappear for days because they’re working nights.”

I stopped. Forced myself to breathe.

“Do you know what a kid does when they’re ashamed?” I asked. “They don’t fill out forms. They don’t raise their hand. They don’t tell the counselor they haven’t eaten since yesterday.”

I touched the photo on the table—my desk, my drawer.

“They just… take a protein bar like it’s stolen gold. And then they run.”

Silence stretched.

Then Mr. Lang looked down at his folder and said the sentence that made my blood go cold.

“We’ll need to inspect your classroom.”

I walked out of that conference room like someone had scooped out my insides and replaced them with ice.

The principal caught my eye from behind the front desk.

Her face changed immediately.

She stepped out from her office and followed me into the empty hallway.

“What did he say?” she asked.

I held up the photo.

Her lips pressed into a thin line.

“He’s coming to inspect,” I whispered.

She closed her eyes for half a second like she was praying.

“Okay,” she said, opening them again. “Okay. We’re going to breathe.”

“Breathe?” I repeated, almost laughing. “He’s going to open my desk drawer and decide whether I’m a criminal.”

She reached for my arm.

“Listen to me,” she said quietly. “You didn’t do this for attention. You didn’t do this for money. You did it because kids were in need.”

“And that’s not allowed,” I said, bitter.

Her voice hardened.

“It should be.”

Then she lowered it again, careful.

“But we have to be smart.”

She leaned closer.

“Before he comes in, I need you to think. Is there anything in that drawer that could be seen as unsafe? Anything that could be twisted?”

I thought of everything I’d ever put in there.

Crackers.

Socks.

A travel-size shampoo bottle.

Deodorant.

Feminine hygiene products.

Gloves.

Hats.

Nothing dangerous.

Nothing illegal.

Just… human.

But humans can twist anything if they want to.

I swallowed.

“There are peanut butter crackers,” I admitted.

Her face tightened.

“Any allergy policies?”

“Yes,” I whispered.

“And are those crackers approved?”

“No.”

We stood there, both understanding the trap.

One allergic reaction.

One angry parent.

One headline that made it sound like I was “endangering children.”

The drawer wasn’t just kindness.

It was risk.

The principal squeezed my arm.

“Go remove anything that could be an allergen,” she said. “Now. Quietly.”

My cheeks flushed.

“So you’re telling me to—”

“I’m telling you to protect yourself,” she cut in. “Because if you fall, the drawer dies with you.”

I stared at her.

And for the first time in years, I realized how lonely leadership is.

How many times she had swallowed her own conscience to survive.

I nodded.

“Okay.”

Back in my classroom, I knelt in front of my desk like I was praying.

The drawer opened with its familiar squeak.

Inside, the supplies looked so ordinary in the fluorescent light.

Like a crime scene made of socks.

I pulled out the peanut butter crackers first.

Then anything with a label that could be argued—anything that could become a weapon in someone else’s mouth.

I replaced them with safer things.

Plain crackers.

Applesauce pouches.

Granola bars without nuts.

I didn’t even know if they were fully safe—nothing ever is—but I tried.

As I worked, my hands shook.

Because it hit me all at once:

I had built a quiet little bridge for kids to cross.

And now adults were setting it on fire.

The bell rang.

Students flooded in.

And I smiled.

Because teachers smile through everything.

A girl in the front row was chewing gum with the intensity of a lawsuit.

A boy near the window had his head down, hoodie up, sleeping.

Marcus walked in late, as usual.

But today he didn’t slide into his seat like a shadow.

He paused near my desk.

His eyes flicked to the drawer.

Then to my face.

He knew something was wrong.

Kids always know.

He didn’t speak.

He just walked to his seat slowly, like he was carrying something invisible.

When the class settled, I started my lesson.

And then the door opened.

Mr. Lang stepped inside with a clipboard.

The room froze.

I felt thirty pairs of eyes turn to him, then to me, then to my desk.

He smiled politely.

“Good morning,” he said. “Don’t mind me.”

Oh, but they did.

He walked to my desk while I stood at the front pretending to explain the Bill of Rights with my voice steady.

He opened drawers.

Top drawer.

Middle drawer.

Then he crouched.

My stomach clenched.

His hand reached for the bottom drawer.

And before I could stop it—before I could even think—

Marcus stood up.

His chair scraped the floor.

Mr. Lang paused.

The room held its breath.

Marcus’s voice came out rough, like it hadn’t been used for something honest in a long time.

“Don’t,” he said.

Mr. Lang straightened slowly.

“I’m sorry?” he asked.

Marcus’s hands were fists at his sides.

“Don’t touch that,” he said again, louder.

A few kids shifted.

Someone whispered, “Dude…”

I felt my heart slam against my ribs.

“Marcus,” I warned, softly.

But Marcus wasn’t looking at me.

He was looking at the man with the clipboard.

The man who didn’t know his life.

The man who thought policies were the whole story.

“That drawer,” Marcus said, voice shaking, “is not yours.”

Mr. Lang blinked.

“I’m conducting an—”

“That drawer,” Marcus cut in, and his voice cracked on the second word, “is why I’m even here.”

Silence.

Heavy.

Like snow before a storm.

Marcus swallowed hard.

“My little brother,” he said, eyes burning, “he’s in sixth grade. He’s small. He gets picked on.”

He pointed at the drawer like it was a witness stand.

“He took deodorant from there last month. Because kids kept calling him names.”

Marcus’s jaw clenched.

“He cried in the bathroom before school. Every day. He’s twelve.”

A few kids stared at their desks.

One girl blinked hard like she was trying not to cry.

Marcus kept going, like once the door opened he couldn’t close it.

“My mom works nights,” he said. “My dad works two jobs. We don’t have… extra. We don’t have backup.”

He looked around the room now, not just at Mr. Lang.

“And you know what?” he said, voice rising. “Half of you took something from there too.”

Gasps.

A ripple of movement.

Kids shifting like the truth was hot.

Mr. Lang’s smile had vanished.

“Marcus,” he said carefully, “this isn’t appropriate—”

“Appropriate?” Marcus laughed, sharp and ugly. “You want to talk about appropriate?”

He pointed at the kids.

“It’s not appropriate that my friend over there keeps a pad in her pocket because she’s scared the school will run out again.”

The girl he pointed to went rigid, face flaming.

I started forward.

But she lifted her chin.

And that stopped me.

Marcus pointed again.

“It’s not appropriate that he pretends he’s not hungry because it’s embarrassing.”

The boy near the window lifted his head, eyes glassy.

Marcus’s voice went quieter, deadly calm.

“And it’s not appropriate that you’re gonna take it away because one parent got mad about ‘handouts.’”

I felt tears burning behind my eyes.

Mr. Lang looked like someone had slapped him with a reality he didn’t want.

He glanced at me.

Then at the class.

Then back to his clipboard like it could save him.

“Thank you,” he said stiffly. “Marcus, sit down.”

Marcus didn’t move.

His whole chest rose and fell like he was holding back something bigger.

Then he said the line that I still hear when I’m trying to sleep:

“You adults love rules more than kids.”

The room went dead silent.

Even the air conditioner seemed to hush.

Mr. Lang’s face tightened.

“Marcus,” he said, voice clipped, “sit. Down.”

Marcus’s hands trembled.

And finally, slowly, he sat.

But his eyes never left Mr. Lang.

Mr. Lang looked at the drawer.

Then, to my shock… he didn’t open it.

He straightened, scribbled something on his clipboard, and walked out without another word.

As the door clicked shut, the room exhaled.

And then the whispers started, fast and electric.

I stood at the front of the room shaking.

Marcus stared at his desk like he’d just ripped his own skin off in public.

I should have scolded him.

I should have sent him to the office.

I should have done what teachers are trained to do when a kid disrupts.

Instead, I did the only thing I could do without falling apart.

I turned back to the board and wrote, in big letters:

WHO DECIDES WHAT WE OWE EACH OTHER?

And the class went quiet again.

Because they knew.

That wasn’t a history question.

That was a life question.

By lunch, the story had moved faster than any official email ever could.

A kid told a kid.

A kid texted a cousin.

A cousin told a parent.

A parent posted online.

And by the time the final bell rang, my phone was buzzing with numbers I didn’t recognize.

I don’t know which part went public first.

Maybe it was the photo.

Maybe it was Marcus’s outburst.

Maybe it was the phrase “secret drawer” that made it sound scandalous.

But that evening, when I opened my laptop, there it was.

A blurry post on a local community page.

No school name.

No teacher name.

Just enough detail for people who lived here to know.

The caption said something like:

TEACHER HIDES “HELP DRAWER” FOR STUDENTS—DISTRICT INVESTIGATING

And underneath it…

The comments.

Hundreds of them.

People I’d never met fighting like my classroom was a battlefield.

Some were kind:

“This is what community looks like.”

“Kids can’t learn hungry.”

“Protect that teacher.”

Some were furious:

“Not the school’s job.”

“Where are the parents?”

“This is enabling.”

“My kid shouldn’t be exposed to this.”

And some—some were the worst kind of loud:

“If you can’t afford kids, don’t have them.”

“Stop rewarding bad choices.”

“This is how you get freeloaders.”

I stared at those words until my vision went strange.

Because none of those people had looked into Marcus’s face when he said his brother cried in the bathroom.

None of them had watched Sarah’s hands bleed from cold.

None of them had seen kids take a granola bar like it was shame.

They were arguing about an idea.

I was living with children.

My email pinged.

Then again.

Then again.

A message from a parent I didn’t know:

Is this you? My daughter says you have a drawer. Please confirm.

Another:

I don’t appreciate this. I will be contacting the district.

Another:

I was a hungry kid once. Thank you. Please don’t stop.

I sat there, alone in my kitchen, laptop glowing like a campfire, and realized something terrifying.

The drawer was never going to be quiet again.

The next day, the principal called an emergency staff meeting.

We crowded into the library before school. Teachers clutching coffee. Faces tense. Whispering in small clusters.

Mr. Lang stood at the front with the principal and two other district people.

He looked different now.

Less polished.

Like he’d slept poorly too.

The principal cleared her throat.

“I know many of you have seen the online discussion,” she began carefully.

“Discussion,” someone muttered.

She continued. “I want to remind staff that we do not engage publicly about internal district matters.”

A few teachers exchanged looks.

Then Mr. Lang stepped forward.

“The district is conducting a review,” he said. “We are aware of concerns—on multiple sides—regarding student safety and equitable access to resources.”

Equitable access.

Such a clean phrase for messy lives.

He glanced down at his notes.

“Let me be very clear,” he said. “No staff member is currently being accused of wrongdoing.”

I felt a few heads turn toward me.

My face burned.

“But,” he continued, “we must ensure that any support provided to students follows policy.”

A teacher in the back raised her hand.

“What policy covers hungry kids?” she asked flatly.

Mr. Lang hesitated.

“We have official referral pathways—”

“And how long do they take?” another teacher snapped.

“And how many kids refuse to use them because they don’t want to be labeled?” someone else added.

The room buzzed.

It wasn’t just my drawer.

It was everyone’s quiet knowledge.

Teachers have been buying kids pencils and snacks forever. We’ve been doing it with our own money while politicians—sorry, while adults with microphones—argue on television about everything except what it feels like to be twelve and hungry.

Mr. Lang lifted his hands.

“I’m not here to debate,” he said quickly.

That line made several teachers laugh, sharp and humorless.

Because of course he wasn’t.

Debate is easy when you don’t have to look a child in the eye afterward.

The principal stepped forward again, voice firm.

“We will be implementing an interim measure,” she said.

My stomach tightened.

“Until the review is complete,” she continued, “staff are not to distribute food or hygiene items directly to students outside of approved channels.”

The library went dead.

I heard someone inhale sharply.

I felt my chest tighten like a vise.

Not to distribute.

Not to help.

Not to do the thing we do every day in a hundred quiet ways.

A teacher near me whispered, “So what are we supposed to do? Watch them?”

The principal’s face looked like it hurt.

“We are going to work on a solution,” she said, voice strained. “But right now we have to protect the school.”

Protect the school.

Not the kids.

The building.

The system.

The liability.

We filed out in silence.

And I walked back to my classroom feeling like someone had taken my hands away.

At 10:17 that morning, I noticed something.

The drawer was open.

Not slightly.

Wide.

Empty.

Not “kids took what they needed” empty.

Cleaned out.

Even the sticky note was gone.

My heart dropped.

I crouched, staring into that hollow space like it was a grave.

Then I saw it.

A new note, taped inside the drawer.

Not in my handwriting.

Thick black marker.

All caps.

STOP TEACHING THEM TO TAKE.

I sat back hard on my heels.

For a moment I couldn’t breathe.

Because that wasn’t policy.

That wasn’t compliance.

That was cruelty.

That was someone standing over a child’s hunger and calling it a lesson.

My vision blurred.

I looked up.

Marcus was watching me from his seat, eyes narrowed.

He stood slowly and walked toward my desk.

He saw the note.

His jaw clenched so tight I thought his teeth would crack.

He didn’t touch it.

He just looked at me and whispered, barely audible:

“They did it on purpose.”

I swallowed.

“Go back to your seat,” I managed.

He didn’t move.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said, voice shaking, “they’re gonna win.”

Something inside me snapped—not into anger, exactly.

Into determination.

“No,” I whispered back. “They’re not.”

That afternoon, I didn’t go home right away.

I sat in my classroom after the last bell, the empty desk drawer staring at me like an accusation.

The principal knocked softly and stepped in.

She looked exhausted.

“I saw the note,” she said quietly.

I nodded.

My throat was too tight to speak.

She sat in the chair across from my desk like she needed a second to be human.

“I hate this,” she admitted.

“I know,” I whispered.

She reached into her bag and pulled out something folded.

A piece of paper.

She slid it to me.

It was a draft.

A proposal.

Not official yet.

But real.

Student Resource Closet Initiative

Purpose: Provide discreet access to basic hygiene items and non-perishable snacks through a monitored, allergy-aware system.

My eyes scanned the page.

It included checkboxes.

Procedures.

Consent forms.

An approval chain.

A list of “approved items.”

It was bureaucracy.

But it was also… a path.

I looked up at her.

“They’ll never approve funding,” I said.

“I know,” she replied.

“Then what’s the point?”

She leaned forward, voice low.

“The point is this,” she said. “If we can’t do it quietly in a drawer anymore, we do it loudly in a closet with policies wrapped around it like armor.”

I blinked back tears.

“And if they still say no?”

Her mouth tightened.

“Then we find another way that doesn’t get you fired.”

I stared at the proposal.

“People online are tearing us apart,” I whispered.

She gave a bitter laugh.

“People online tear apart everything,” she said. “It makes them feel powerful.”

She sobered.

“But here’s what I learned the hard way,” she continued. “The loudest people in the comments are rarely the ones showing up in real life.”

I looked down at the empty drawer again.

The note still taped inside like a bruise.

“And what about the kids?” I asked. “What do I tell them tomorrow when they need something?”

The principal’s eyes softened.

“You tell them you still see them,” she said. “Even if the adults are being… ridiculous.”

She stood, then hesitated at the door.

“Mrs. Miller,” she said, voice steady, “I can’t officially tell you this.”

I looked up.

She held my gaze.

“But check your classroom mailbox in the morning.”

Then she walked out.

The next morning, I opened my mailbox.

Inside was a plain envelope.

No return address.

Just my name.

I opened it with trembling fingers.

Inside were gift cards.

Not from a business with a logo—just generic prepaid cards and cash tucked into a folded note.

The note said:

WE WERE HUNGRY KIDS ONCE. KEEP GOING.

I stared at it until my eyes burned.

Then I looked around the hallway.

Teachers were pretending not to watch me.

But I could feel it.

The quiet solidarity.

The wordless decision being made in a hundred hearts:

We’re not letting this die.

In my classroom, Marcus came in early.

He hovered by my desk.

“Is it gone?” he asked, voice tight.

I opened the drawer.

Empty.

I’d left it empty on purpose. The district directive was clear. The review was active.

Marcus looked like someone punched him.

Then I reached into my tote bag.

Not my drawer.

My bag.

And pulled out a small paper sack.

I slid it into a cabinet behind my desk—one Mr. Lang had never inspected because it wasn’t labeled “drawer.”

Inside were plain crackers, socks, travel-size soap, and a stack of envelopes.

On each envelope I’d written a single word:

TAKE.

Marcus stared.

His eyes flicked to me.

“You’re gonna get in trouble,” he whispered.

I met his gaze.

“Marcus,” I said softly, “I’m not doing this to be a hero.”

He swallowed.

“Then why?”

I looked at the kids filling the room.

At the tired eyes.

The brave faces.

The shoulders that carried too much.

“Because,” I said, voice steady, “I refuse to let a sticky note full of cruelty be the last thing they learn about adults.”

Marcus blinked hard.

Then, barely, he nodded.

And for the first time since this started, he smiled—small, fierce, like a candle refusing the wind.

Two weeks later, the district held a public meeting.

Not about me, officially.

About “student resource protocols.”

About “equity.”

About “safety.”

But everyone knew what it was really about.

The auditorium was packed.

Parents.

Teachers.

Community members.

Some angry.

Some supportive.

Some just curious, hungry for drama like it was entertainment.

The principal sat in the front row, hands folded tight.

Mr. Lang stood near the side, clipboard gone, face tense.

I sat beside Marcus’s dad.

He hadn’t said much when he arrived, just nodded at me like a man who didn’t waste words.

Marcus sat with his arms crossed, eyes sharp.

A board member—just a person with a microphone—cleared their throat.

They talked about liability.

About procedure.

About accountability.

The words floated over us like fog.

Then they opened the floor for public comment.

Hands shot up.

A woman stood first.

“This is not the school’s job,” she said loudly. “Parents need to take responsibility.”

Murmurs.

A man stood next.

“My kid came home asking why other kids get free stuff,” he said. “It creates resentment.”

More murmurs.

Then a grandmother stood.

Her voice shook, but she didn’t flinch.

“I raised five kids,” she said. “I worked nights. There were times the lights almost got shut off.”

The room quieted.

She swallowed.

“My grandson is in middle school here,” she continued. “And he told me there’s a place at school where kids can get deodorant without being laughed at.”

Her eyes shone.

“I don’t care what you call it,” she said. “Call it a closet. Call it a pantry. Call it whatever makes the adults feel comfortable.”

Her voice hardened.

“But don’t you dare tell me a child should suffer to teach their parents a lesson.”

The room erupted—clapping, groans, people talking over each other.

Controversy.

The kind that makes comment sections explode.

But for once, it wasn’t empty.

It was real.

Marcus’s dad stood slowly.

He looked uncomfortable holding a microphone, like he’d rather lift boxes than words.

“I’m Marcus’s father,” he said.

The room shifted.

Some people recognized the name from the post.

He cleared his throat.

“I work,” he said simply. “I work all the time. I’ve missed birthdays. I’ve missed games. I’ve missed… a lot.”

His voice thickened.

“And I still fall short.”

Silence.

He looked at the board.

“You want to talk about responsibility?” he asked, calm but cutting. “Fine.”

He gestured toward the crowd.

“How many of you have been one missed paycheck away from losing everything?”

A few people shifted, uncomfortable.

He nodded slowly, like he’d expected that.

“See,” he said. “That’s the problem. Folks think poverty is a personality trait.”

Oof.

The room stirred.

He continued, quieter.

“My boy came home smiling,” he said, voice breaking. “Smiling. After months.”

He swallowed hard.

“Because one teacher didn’t treat him like trash.”

He looked out over the crowd now.

“You can argue all night about who deserves what,” he said. “But I’m telling you this: if you punish the people who help, don’t act surprised when the world gets colder.”

Then he sat down.

And even some of the angry people went quiet.

When the meeting ended, nobody “won.”

There was no perfect resolution.

No neat movie ending.

But there was something else.

People lingered.

Talked.

Looked at each other differently.

A woman who’d been angry in the comments approached the grandmother and spoke softly.

A man who’d complained about resentment stood near the back, staring at the floor like he was rethinking something.

And Mr. Lang—district compliance himself—walked toward me.

I braced for impact.

He stopped a few feet away.

His face looked tired in a human way now.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said quietly, “I wanted you to know something.”

I didn’t speak.

He glanced around, then lowered his voice.

“I grew up in a house where the fridge was empty sometimes,” he admitted.

My breath caught.

He swallowed.

“And I hated it,” he said. “I hated needing help.”

He looked at me.

“That’s why I do this job,” he said. “Because I’m scared of chaos.”

I stared at him.

He nodded slowly, like he was admitting a flaw.

“But,” he continued, voice rough, “watching that room tonight… I realized something.”

He exhaled.

“Protocols aren’t supposed to replace compassion,” he said. “They’re supposed to protect it.”

He looked away for a second, then back.

“The district will approve a monitored resource closet,” he said. “Limited items. Allergy-safe. Discreet access.”

My chest tightened.

“And the drawer?” I whispered.

His mouth twitched, almost a smile.

“The drawer,” he said, “will become a closet with a lock and a sign-in sheet.”

I should’ve been thrilled.

I was.

But grief still flickered in me—grief for the simplicity of kindness without paperwork.

I nodded.

“Thank you,” I said, voice trembling.

He paused.

Then he said something so quiet I almost didn’t hear it.

“I’m sorry it took an angry comment section to make people listen.”

Then he walked away.

The next Monday, we opened the closet.

Not fancy.

A converted storage space near the nurse’s office.

Shelves with bins.

Plain labels.

Hygiene.

Snacks.

Socks.

Gloves.

A “take what you need” policy written in careful language.

Everything approved.

Everything documented just enough to satisfy the adults.

But the heart of it—the dignity—was still there.

Kids came in one at a time.

Quiet.

Quick.

Some couldn’t meet my eyes.

Some whispered “thank you” like it hurt.

One boy took deodorant and stood there for a second, holding it like it was permission to exist.

A girl took two pads and blinked rapidly, shoulders tight, like she was trying not to fall apart.

And then Marcus came in.

He hovered in the doorway.

Looked at the shelves.

Looked at me.

“It’s not the drawer,” he said.

I nodded.

“No,” I admitted. “It’s not.”

He walked in anyway.

He took a pair of socks.

Then—slowly—he placed something on the shelf.

A new winter hat.

Not expensive.

Just warm.

He glanced at me like he didn’t want me to make a big deal out of it.

“My pop says you can’t take without giving,” he muttered, repeating his note from before like it was a rule of the universe.

I swallowed hard.

“Your pop’s a good man,” I said softly.

Marcus’s jaw tightened, like he didn’t want to cry.

Then he nodded once and walked out.

That night, the online arguments continued.

They always will.

People will always fight about whether helping is “enabling” or “compassion.”

They’ll argue about responsibility and fairness and what schools should be.

They’ll write long comments from warm houses.

But here’s what I learned—really learned—when my drawer went public:

Most of the world’s cruelty doesn’t come from monsters.

It comes from people who’ve never been hungry enough to understand what hunger turns you into.

And most of the world’s kindness doesn’t come from saints.

It comes from tired people who decide, quietly, not today.

Not on my watch.

Not in my classroom.

So if you want something to argue about in the comments—fine.

Argue about this:

Should a child have to earn dignity?

Should they have to prove they “deserve” socks?

Should they have to pass a morality test for toothpaste?

Should they have to be perfect to be helped?

Because I’ve taught American history for thirty years.

I’ve taught about rights people fought for, bled for, died for.

And I’ll tell you what I believe, with my whole chest:

A country isn’t measured by its speeches.

It’s measured by whether a hungry kid can walk into a room, take what they need, and still feel like a human being.

And sometimes…

Sometimes the only thing standing between a child and despair isn’t a policy.

It’s a shelf.

A quiet door.

And one adult who refuses to look away.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta