PART 1 – The Second Explosion

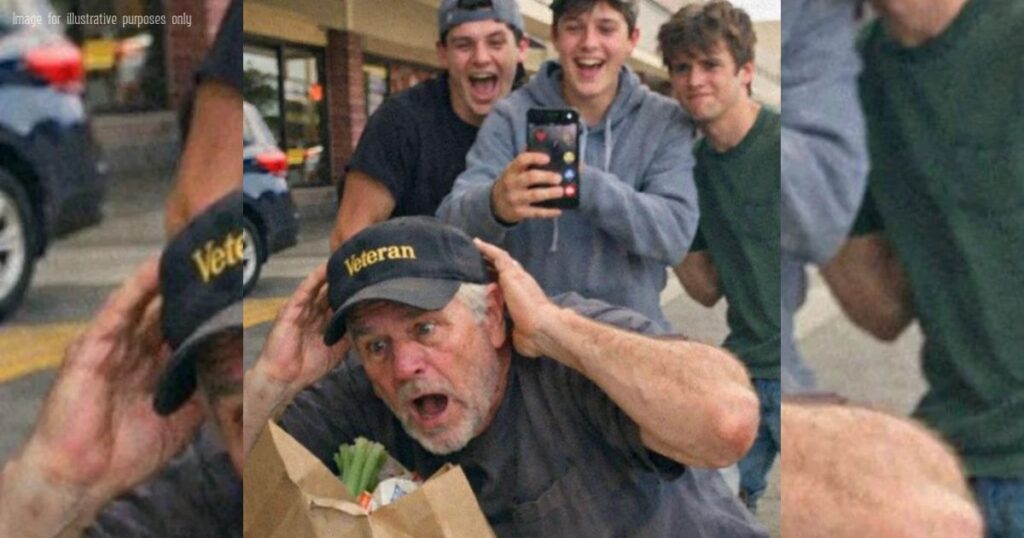

They set off a fake blast behind a combat veteran just to watch him fall apart on camera, his body hitting the sidewalk while hearts and laughing emojis floated across their live stream.

They thought they were filming a prank for views; they had no idea they’d just pressed “record” on the worst day of his life—and the beginning of theirs.

The sound was sharp enough to make everyone on the sidewalk flinch.

It wasn’t a real explosion, just a hidden speaker in a backpack and a burst of compressed air, but it was loud and sudden and mean.

Shoppers turned, hands pressed to their chests, looking for smoke, for fire, for something.

Only one person went down.

The older man in the faded baseball cap dropped his grocery bag and folded to the pavement like his bones had been yanked out.

He curled in on himself, arms over his head, knees pulled tight, shaking so hard the plastic bag beside him rattled.

His cap rolled away, and I saw the words stitched across the front in gold thread: “Veteran.”

Not a joke, not a prop, not an actor—just a human being whose nervous system had already heard too many real blasts.

“Yo, look at him!” the tall boy shouted, phone held high in one hand, backpack strap in the other.

His live stream was still going; I could hear the digital chime of new comments even from where I sat in my car.

“This is insane, he’s really freaking out, guys, keep sharing this!”

Behind him, his two friends laughed, one filming from a different angle, the other checking numbers on the screen like it was a game.

I was halfway out of my car before I even knew I’d opened the door.

My name is Maya Ortiz, and I’ve spent fifteen years as an ER nurse watching people arrive at their worst moments.

But I had never watched a crowd stand back and let three teenagers turn a veteran’s panic attack into entertainment.

My heart was pounding so hard I could feel it in my throat as I sprinted toward them.

“Stop filming and call 911!” I shouted, weaving through shopping bags and startled faces.

I dropped to my knees beside the man, sliding my purse away so it wouldn’t dig into him.

His hands were clamped over his head, fingernails digging into his scalp, breath coming in fast, ragged bursts.

“Sir, you’re safe, you’re not there, you’re here, on a sidewalk, you’re safe,” I said, my voice steady even though I was boiling inside.

Instead of helping, the tall boy swung his phone toward me.

“We’ve got a hero, guys, look at this,” he told his viewers, grinning into the camera.

“She’s really going for it, isn’t she? Ma’am, you okay if we tag you?”

His tone said he thought this was all some kind of performance.

I ignored him and focused on the man.

“Sir, can you hear me?” I asked, keeping my voice low and calm.

His eyes were squeezed shut, face pale, shoulders trembling.

“I’m Maya, I work at a hospital, I’m right here with you, you’re not alone.”

His lips moved, barely.

“Make it stop,” he whispered, voice cracked and small.

“Please, make it stop.”

I swallowed hard; I’d heard that same sentence in a different hospital room a decade ago—from my father, the night before he gave up.

I grabbed my phone with one hand and dialed 911 while keeping my other hand gently on the veteran’s shoulder.

“Male, approximately late sixties, possible panic attack and fall,” I told the dispatcher, forcing my voice to stay even.

“We’re outside the north entrance of the shopping center, he’s disoriented, may have hit his head, he’s a veteran and he’s terrified.”

Behind me, I heard the boys still talking to their audience.

“Cut the setup,” one of them muttered, not realizing his mic picked it up.

“Just keep the part where he drops and curls up, that’s the crazy part.”

“Yeah,” the tall one agreed, excitement still in his voice.

“Nobody cares how we did it, the freak-out is what’s gonna blow up.”

My stomach twisted.

This wasn’t some horrible coincidence they’d stumbled onto.

They had planned the loud sound, waited for him, watched him, and when he collapsed, they treated his pain like a special effect.

I forced myself to breathe slowly so he wouldn’t feel me shaking.

“Sir, what’s your name?” I asked, leaning closer so he could hear me over the murmur of the crowd.

“Leo,” he breathed, the word almost lost.

“Leo Parker.”

“Okay, Leo, stay with me,” I said softly. “Help is on the way.”

A small circle had formed now—people with shopping bags and coffee cups, watching, unsure whether to step in.

Some held their phones, pointed not at Leo but at the boys who were still streaming.

“Somebody go flag down the ambulance at the street,” I called without looking up.

A woman’s voice answered, “I’ll do it,” and the sound of running footsteps faded toward the parking lot.

Sirens wailed faintly in the distance, growing louder with each passing second.

Leo’s fingers slowly loosened from the back of his head, his eyes blinking open just enough for me to see confusion and shame fighting in them.

“I’m… sorry,” he whispered, as if he’d done something wrong.

My throat burned.

“You have nothing to be sorry for,” I said quickly.

“This is not your fault.”

Over my shoulder, I let my gaze flick to the boys for the first time.

The tall one lifted his chin like this was a confrontation he could win.

A moment later, the ambulance pulled up and two paramedics jogged over with a stretcher.

One knelt by Leo’s side, assessing him with practiced hands.

“How long has he been like this?” he asked, eyes flicking up to me.

“Long enough for them to get a few hundred people watching,” I answered, my voice louder than it needed to be.

The paramedic’s jaw tightened, but he said nothing as they gently transferred Leo onto the stretcher.

As they secured him, Leo’s hand groped blindly until it found mine.

“Please,” he whispered again, eyes glassy.

“Don’t let them turn me into a joke.”

“I won’t,” I promised, squeezing his fingers before they slid his hand under the blanket.

I stepped back to give the paramedics room, watching the stretcher roll toward the open doors of the ambulance.

The boys were still filming, narrating, trying to turn the sirens and uniforms into a dramatic ending for their audience.

It felt like watching someone dance next to a grave.

When the doors closed and the ambulance pulled away, I finally turned to face them.

The tall boy still had his phone up, red recording light blinking, confidence starting to crack around the edges of his smile.

His friends shifted from foot to foot, eyes darting between me and the screen.

For the first time since the blast, I let him see exactly how angry I was.

“You think you’re chasing views,” I said, meeting the lens so his whole audience could hear me, “but you just filmed the evidence that’s going to change your life forever.”

PART 2 – The House Called Second Tour

The red and blue lights faded in the distance, but the echo of that fake blast stayed in my chest.

People slowly drifted back to their errands, shaking their heads, muttering about “kids these days,” and checking their phones for the clip they’d just watched live instead of stepping forward.

The three boys huddled near a trash can, screens glowing, their excited whispers a low buzz I wanted to swat.

I walked toward them anyway.

“Names,” I said, stopping just out of reach of the tallest one’s camera.

I kept my tone flat, clinical, the way I used to talk to combative patients.

He lifted his chin, still trying to act like none of this could stick to him.

“Why? You gonna sue us for hurting your feelings?”

“My name is Maya Ortiz,” I answered, ignoring the jab.

“And that man’s name is Leo Parker. He’s on his way to the hospital because you thought his trauma might be good for your followers. The paramedics are going to ask how long he was on the ground and what triggered his episode. I’m going to tell them exactly what I heard and saw. I suggest you think about whether you want to lie on camera twice.”

The smallest boy shifted his weight, his sneakers squeaking on the pavement.

He wore a sports hoodie and had the nervous energy of someone who wasn’t used to being in trouble.

“I’m Jaden,” he mumbled, not looking at me.

The one with the camera still rolling added, “Tyler,” without much volume.

The tall boy exhaled through his nose, annoyed.

“Chase,” he said, rolling his eyes. “It was a prank, okay? It wasn’t that deep. People prank veterans online all the time. He’s fine.”

“Pranks end when everyone’s laughing,” I said.

“Did he look like he was laughing to you?”

For a second, something uncertain flickered across his face, then he shook his head like he could toss it away.

“It’s not illegal to film in public,” he muttered, more to the phone than to me.

“You’re right,” I replied. “It’s not illegal to film. But it might be illegal to create a situation that sends someone to the hospital and then stand there narrating instead of helping. And you didn’t just film. You set him up. I heard you.”

I didn’t wait for an answer.

Instead, I took my own phone out, pretending to check a message while I tapped the option that saved the live stream I’d just watched.

The app had already cached part of it; with a few more taps, the clip was sitting in my gallery, the boys’ voices clear above the shaky video of Leo collapsing.

“Cut the setup, just keep the part where he drops,” Chase had said. It was all right there.

On the drive to the hospital, the radio was just noise.

Every time I blinked, I saw Leo curled on the concrete, hands over his head like he expected debris.

Every time my fingers tightened around the steering wheel, I heard my father’s voice again in the hospital years ago, asking me, “Do they think I’m crazy, or do they just not want to see?”

Back then, someone had filmed his panic in a grocery store aisle and posted it with a laughing caption. He hadn’t lived long enough to see it taken down.

At the emergency desk, I flashed my work badge.

“I was at the scene,” I told the triage nurse. “Older male, possible head injury and panic episode. They brought him in a few minutes ago.”

She nodded toward a curtained room down the hall.

“They’re evaluating him now. You can give your statement to security, and the attending might want to talk to you too.”

Leo lay on the bed, eyes closed, breathing slower now.

Someone had placed a soft collar around his neck as a precaution.

The fluorescent lights made his skin look gray, and the lines around his mouth had deepened into trenches.

I stayed near the foot of the bed until the attending physician finished, then stepped closer when he left.

“Mr. Parker,” I said gently.

His eyelids fluttered and opened halfway.

“It’s Maya. I was with you outside the shopping center. You’re in the hospital now, and you’re safe.”

He swallowed, Adam’s apple bobbing.

“Did I… grab anyone?” he asked hoarsely.

“Did I scare any kids? Sometimes I… I forget where I am.”

“No,” I said.

“You didn’t hurt anyone. You fell. You were having a panic reaction to a loud sound. You protected yourself, that’s all. The only people who should be ashamed are the ones who thought it was funny.”

His gaze shifted to the side, unfocused.

“I heard laughing,” he whispered. “For a second, I thought it was my squad, you know? The way they used to laugh when somebody tripped over a sandbag. Then it didn’t sound right. Too young. Too light. Like nothing heavy had ever landed on them.”

My chest tightened.

“There were some teenagers,” I admitted.

“They had a speaker in a backpack. They made the sound on purpose and livestreamed you when you fell. I called for help. The paramedics brought you here.”

Leo closed his eyes again, and for a moment I regretted telling him.

Then he nodded very slowly.

“Thank you for not lying to me,” he said. “That’s worse than the noise, sometimes. People pretending it’s not as cruel as it is.”

Security came to get my statement, then a police officer.

I played the clip for them, kept my voice level as I described what I’d witnessed, signed the forms with steady hands that only shook once I was back in my car.

I knew my part was “done” for now, at least on paper, but the promise I’d made to Leo stuck like a thorn in my mind.

I opened my phone again and paused the video at the frame where his cap lay on the sidewalk.

“Veteran,” the brim read.

Under that, in smaller print, a logo and name: “Second Tour House.”

A nonprofit, maybe. A resource center. It wasn’t a brand I recognized, which meant it was probably local and underfunded.

I typed the name into a search bar and found a simple website.

There was a picture of a worn brick building with a ramp out front and a flag on the porch.

The tagline read, “For those who came home and still feel lost.”

There was also a phone number.

I stared at the digits for a long moment.

I could tell myself this wasn’t my job. I was an ER nurse, not a reporter, not an activist, not a professional fixer of broken systems.

But Leo’s voice kept replaying in my head: Don’t let them turn me into a joke.

My father’s voice layered over it: Do they just not want to see?

I hit call.

The line rang twice before a deep, tired male voice answered.

“Second Tour House, this is Gus,” he said.

“Hi, Gus,” I replied, my throat suddenly dry. “My name is Maya Ortiz. I’m a nurse at City General. One of your veterans just came through our ER after something happened at the shopping center. His name is Leo Parker.”

There was a long pause on the other end.

“Leo?” the man repeated, his tone changing from routine to alarm.

“What happened? Is he alive?”

“He’s alive,” I said quickly. “He’s stable for now. But I think you should see what they did to him. And I think you’re going to want to see the video before the rest of the internet does.”

PART 3 – Honor Line

Gus sounded older than the picture I eventually matched to his voice.

In the photo on the Second Tour House website, he stood with a group of men and women in front of the brick building, broad shoulders, intense eyes, short gray hair.

In person, when I met him an hour later in the hospital waiting room, he looked like a tree that had been struck by lightning and decided to keep standing out of sheer stubbornness.

Beside him was a woman in her early fifties with a calm, steady gaze and a soft scarf wrapped around her neck.

“I’m Andrea,” she said, shaking my hand firmly. “I run most of the day-to-day at the house. Leo’s there almost every afternoon. He says the coffee is terrible, but he never misses a cup.”

I tried to smile and couldn’t quite get there.

“He’s resting now,” I said. “The doctors are monitoring him for a possible concussion and complications from the panic episode. They think he’ll physically recover, but…”

I let the sentence trail off. There were injuries that didn’t show up on scans.

“We know ‘but,’” Gus said quietly.

“They sent us home with a whole bag of ‘but’ and told us to make something of it.”

He sat down heavily on one of the plastic chairs, elbows on his knees. “Show us,” he added. “Show us what they did.”

I pulled out my phone and opened the saved clip.

I’d cut it to start the moment the speaker blared and Leo dropped, but all the audio was intact.

We watched in silence as the fake blast went off, as Leo’s body folded, as Chase’s voice rose in gleeful narration.

When the words “cut the setup, just keep the part where he drops” came through, Andrea pressed her lips together and looked away.

Gus didn’t look away.

A vein pulsed in his temple, his jaw tightening with each second that ticked by on the scrub bar.

When it ended, the waiting room felt too small.

A TV in the corner played muted news about something unrelated, children shuffled past with coloring books, and somewhere a vending machine hummed.

It was all painfully ordinary in the face of something that felt like it should have stopped the world for at least a moment.

Gus leaned back and exhaled slowly.

“I’ve seen worse things,” he said. “But I saw those things overseas, where nobody pretended it was entertainment. This? This is something else.”

His eyes shifted to me. “You called us before you called anyone else?”

“I already talked to security and the police,” I said.

“They have the footage. An officer said they’re reviewing potential charges. But video moves faster than paperwork. The boys were streaming this live. I don’t know how many people saw it already or how many screen recordings are out there.”

Andrea folded her hands in her lap.

“Thank you for not just walking away after you did your ‘official’ duty,” she said. “We’ve had enough of people checking a box and moving on. Gus is right; this is something else. It’s cruelty with an audience.”

“You think the house should respond?” Gus asked her.

Andrea didn’t answer immediately.

She turned the question over in her mind, and I could practically see the headlines she was trying to avoid and the battles she was willing to fight.

“Only if we do it without becoming another angry clip,” she said finally. “We can’t be the mirror image of those boys, just older and louder.”

Somewhere else in town, in a two-story house with shiny windows and a wide driveway, Chase wasn’t thinking about mirror images or ethics.

He was thinking about numbers.

“Twenty-two thousand live viewers,” he told his phone, pacing his bedroom with its unmade bed and walls covered in posters for content creators he idolized.

He’d ended the stream when the ambulance left, switching it to private, heart still racing.

“Imagine if we cut the boring parts and re-upload. No way this doesn’t trend on StreamLoop.”

Tyler sat at the desk, staring at the paused video on the laptop screen.

From this angle, you could see Leo’s hand twitch as he reached for a bag that wasn’t there anymore.

“You heard that nurse,” Tyler said. “She’s talking to the cops. We might want to… think about what we post.”

Chase waved his free hand dismissively.

“She can be mad all she wants. We didn’t touch him. We just made a sound. He fell on his own. And everybody films everything these days. That’s the whole point of the app.”

He flopped onto the bed. “Besides, people love veterans. They’ll feel bad for him and watch more. We’re giving them a story.”

In the corner, sitting on an office chair he’d tilted back dangerously far, Jaden stared down at his thumbs.

“My brother’s not going to think it’s a story,” he muttered.

“He ships out in six months. If someone did that to him, my mom would lose her mind.”

Chase looked over, then away.

“Come on, man. You know we wouldn’t do it if we knew he was going to freak out that bad. We thought he’d jump, maybe yell, that’s it. It’s not like we planned… all that.”

He gestured vaguely at the screen.

Tyler scrubbed the video back ten seconds, then played it with the sound off.

Without the audio, it looked even worse.

An older man walking with a small bag. A burst of motion. His body dropping. Three kids standing over him with phones out, faces lit by blue light.

“If we post this now,” Tyler said quietly, “we’re not the ones controlling the story. Everybody else is.”

Across town, on a couch that had seen better days, Leo’s daughter held her phone so tight her knuckles whitened.

Someone from her office had messaged her a link with the caption, “Is this your dad?”

She had clicked, heart stuttering, and watched her father’s terror unfold in the palm of her hand.

Her husband reached over and gently pried the phone from her fingers.

“Don’t watch it again,” he said. “We’ll go to the hospital. We’ll see him in person. That’s what’s real.”

“But everyone else is seeing that,” she whispered. “Not the man who reads to our grandkids every Sunday. Just that.”

Back in the waiting room, Gus’s phone buzzed with a notification.

He frowned and opened it, then held the screen up for Andrea and me to see.

A local account on the video platform had already reposted the clip with a caption in bold letters: “Teenagers torment veteran with PTSD for fun.”

“Did you send this?” Gus asked me.

“No,” I said quickly. “I haven’t shown it to anyone except you two and the police.”

“There were thousands of people on that stream,” Andrea reminded us softly. “It only takes one to hit ‘save’ and ‘share.’”

The view count ticked upward in real time.

Hundreds. Thousands. Comments flooding in from people who didn’t know Leo, or the shopping center, or our town.

Some were furious, calling the boys monsters. Some were somehow making jokes, as if you could watch a man curl into himself from fear and still find punchlines.

“We need to respond,” Gus said, standing up.

“Before this turns into another round of people using him for content from the opposite side. Either way, he’s the clip, and they’re the ones performing.”

Andrea nodded. “We call a meeting at the house,” she said. “Every vet who wants to come. We figure out how to stand up for Leo without turning into a headline ourselves.”

She looked at me.

“Maya, you said you’d promised Leo not to let them turn him into a joke,” she added. “If you’re willing, I think you just found a room full of people who plan on helping you keep that promise.”

I glanced through the small window in Leo’s door.

He was sleeping now, chest rising and falling in a fragile rhythm.

On the bedside table, someone from the staff had placed his cap, brim facing the ceiling, gold letters catching the light.

“I’m in,” I said.

“Tell me when and where.”

PART 4 – When the Town Watched Itself

The meeting at Second Tour House felt like a storm gathering in a small space.

The building itself wasn’t big, just a converted two-story home with mismatched chairs and a faint smell of burnt coffee, but that night every seat was taken.

Some of the faces in the room were lined and weathered, others younger, but they all turned toward the television mounted on the wall when Gus picked up the remote.

He paused for a breath, then hit play.

Nobody spoke while the video ran.

A few people cursed under their breath when the blast sounded and Leo dropped, hands clasping behind their necks as if their bodies remembered a motion they hadn’t made in years.

When Chase’s voice came through, light and eager, describing the “content” in front of him, a woman in the back pressed her fingers hard against her eyes.

Andrea watched the room more than the screen, tracking every flinch.

When it was over, the silence was heavy.

It wasn’t the kind of silence that comes from lack of words.

It was the kind that comes from having too many.

“That’s my Tuesday morning group,” a soft voice said at last.

A man in his early thirties, younger than most, sat near the door, elbows resting on his knees.

“Leo always brings extra donuts and complains they’re too sweet. He tells the same story about how his grandson cheats at card games. That’s him.”

“He’s us,” another person said.

“He’s every one of us who’s ever hit the floor when a car backfired.”

“And they thought it was funny,” someone else added. “They thought they could just edit out the part where they caused it and keep the rest like a highlight reel.”

Gus held up a hand, palm out.

“We could spend all night listing what’s wrong with this,” he said. “And we’d be right every time. But Leo doesn’t need us to sit in this room and get louder and angrier. He needs us to decide what we’re going to do.”

A man with a cane tapped it against the floor.

“We go to those boys’ houses,” he said. “We line up on the sidewalk and stare at them the way they stared at him. Let them feel what it’s like to have eyes on you when you’re scared.”

Several heads nodded; the idea carried a certain satisfying symmetry.

“And then what?” Andrea asked gently.

“We become another video? ‘Veterans mob teenagers’? We know how fast a clip can be cut and twisted. We know what they’ll show and what they’ll leave out. I’m not saying we do nothing. I’m saying we chose uniforms once already. We know the difference between a mission and chaos.”

Murmurs rippled through the room.

Nobody liked the idea of looking passive.

But nobody wanted to see their faces on the same screen that had just shown Leo curled on the sidewalk.

A woman near the front raised her hand.

“If people are going to talk about this,” she said, “let them hear from us directly. We can call the school. The families. The police. We can go to the community, not to the front yard. We can tell them what this does to someone like Leo, what it could do to their own kid who comes home with the same ghosts.”

“And we show up where it matters,” another added.

“Town hall, school board, church basements, anywhere people gather. We don’t just ask for punishment. We ask for change. Policies. Programs. Something that lasts past the outrage.”

Gus looked at me.

“You’ve been quiet,” he said. “What do you think, nurse?”

I took a breath.

“I think your anger is the most human thing in this room,” I said. “And I think if we only use it to scare three boys, we’ll miss a chance to change the people watching. This video is everywhere now. People are arguing online like it’s a sport. Some want those kids locked up forever. Some say it’s ‘just a prank.’ None of them are talking about what Leo needs next week, or next month.”

Andrea nodded slowly.

“So we do both,” she said. “We support charges where they’re appropriate, because accountability matters. And we insist the solution doesn’t stop there. We demand education, service, actual face-to-face time with veterans, not just online lectures.”

Gus pointed the remote at the muted television, where replay numbers and angry emojis scrolled.

“The town’s having a conversation with itself in the comments section,” he said. “Maybe it’s time it did it in person.”

The town did.

Within two days, the school district announced a community meeting in the high school auditorium.

Officially, it was a “forum on digital responsibility and respect for veterans.”

Unofficially, everyone knew what it was really about.

On the night of the meeting, the parking lot looked like the mall at holiday season.

Cars filled every spot, then lined the street.

Parents arrived in groups, some hugging their kids close, some pulling them along by the wrist, faces tight.

Students clustered near the entrance, whispering, pretending not to stare at the cluster of veterans walking up the ramp together.

Inside, the auditorium buzzed with a nervous energy.

A banner over the stage read “Community Voices Night,” taped slightly crooked to the curtain.

On the stage sat a panel: the principal, a police lieutenant, a counselor, and Andrea. There was an empty chair with a reserved sign: “Second Tour House – Representative.”

Gus refused the spot, choosing instead to sit in the front row with the others, arms folded, presence loud without a microphone.

In the second row, flanked by their parents, sat Chase, Tyler, and Jaden.

They looked smaller without their phones in their hands.

Chase’s hair was neatly combed in a way that looked more like his mother’s decision than his own.

Tyler stared at the floor, jiggling his knee in a relentless rhythm.

Jaden kept his hands clasped together, thumbs tracing invisible lines across his knuckles.

The principal stepped up to the podium, cleared his throat, and tried a practiced smile.

“Thank you all for coming,” he began. “We’re here tonight because something happened in our community that has affected many of us deeply. A video was recorded and shared that showed harm to a member of our community, a veteran named Leo Parker. We’re here to talk, to listen, and to decide how we move forward together.”

He gestured to the police lieutenant, who summarized, in carefully neutral language, the ongoing investigation.

“We are reviewing the evidence, including video recordings and witness statements,” the lieutenant said. “We’re considering charges related to reckless endangerment and failure to render aid. Because some of those involved are minors, there are privacy protections in place. However, I can assure you that we are taking this seriously.”

A murmur ran through the crowd: some relief, some impatience.

A man stood up near the back.

“So what now?” he called. “We let three kids ruin a man’s life and say ‘don’t do it again’?”

Andrea leaned toward her microphone.

“If I may,” she said. “I want to remind us that Leo’s life is not ruined. He is hurt, and he is shaken, but he is also stubborn and kind and very much alive. His story did not end on that sidewalk, and it cannot end in a comment thread either.”

Her gaze swept the room.

“My name is Andrea Brooks,” she continued. “I’m a veteran, and I work at Second Tour House. I’ve seen what happens when people come home and feel invisible. The opposite of invisible is not ‘viral.’ It’s being seen as a whole person, not a moment of pain.”

She let that sit for a second.

“Many of you are angry,” she said. “So am I. So are we. But anger is a starting point, not a plan. Here’s what we’re asking for: accountability through the justice system where appropriate, yes. But also mandatory education about trauma and respect, time spent with veterans at places like Second Tour House, and ongoing programs in this school that teach our kids to put their phones down long enough to see the human being in front of them.”

Parents nodded.

Some students shifted, uncomfortable.

On the panel, the counselor added that the school would be expanding mental health resources and digital literacy programs, trying to turn a crisis into a curriculum.

In the front row, Gus leaned toward me.

“This is good,” he murmured. “It’s not enough, but it’s a start.”

A woman from the back raised her hand, voice shaking.

“My son is one of those boys,” she said. “I’m not proud of what he did. Nothing I say will excuse it. But I’m scared. I’m scared his entire life will be defined by fifty seconds of the worst decision he’s ever made. I don’t want him to be destroyed. I want him to learn.”

Her words hung in the air like a question aimed at the entire room.

I stood up before I could talk myself out of it.

“I’m the nurse who was there,” I said, my voice louder than I felt. “My name is Maya. I called for help. I held Leo’s hand. I heard what those boys said while he was on the ground. I’m angry. I won’t pretend I’m not. But I don’t want to see three more broken people added to the pile. I want them to stand in front of Leo one day and understand the weight of what they did. I want that to matter more than the views.”

Dozens of eyes turned toward the three boys.

Their shoulders hunched under the attention, faces flushed.

For the first time since that morning, they weren’t hiding behind screens.

The principal cleared his throat again.

“As we move forward,” he said, “there will be consequences. Legal, educational, personal. But there will also be chances—chances to listen, to serve, to repair what can be repaired. The justice system will play its part. So will we, as a community.”

He looked toward the police lieutenant, who nodded once.

“In the coming days,” the officer said, “we’ll be meeting with the families involved to discuss charges and potential plea agreements. Part of that process may include structured community service at organizations like Second Tour House.”

He didn’t say “for the three boys in the second row,” but he didn’t need to.

As the meeting ended and people began to file out, talking in clusters, I caught a glimpse of something unexpected.

Out in the hallway, away from the crowd, Jaden stood alone by a bulletin board.

He pulled out his phone, stared at it for a long moment, then slipped it back into his pocket without opening the camera.

It was a small thing.

But for the first time all day, it felt like a crack in the wall instead of just another brick.

PART 5 – Charges and Crossroads

The official notice came three days later, printed on heavy paper that tried and failed to make the words feel less sharp.

The county prosecutor’s office announced that they were filing juvenile charges against the three boys involved in the incident at the shopping center.

The list included reckless endangerment, creating a public nuisance, and failure to render aid.

The words were clinical, but the undertone was clear: this was not being written off as “just a prank.”

I read the statement online during a lunch break, scrolling past a flood of comments that ranged from measured to unhinged.

Some people demanded the maximum penalty the law allowed.

Others insisted that any consequence beyond a slap on the wrist would be “ruining young lives.”

Very few seemed to be thinking about Leo beyond the role he played in their argument.

At the hospital, Leo was making slow progress.

The concussion symptoms were easing, though he still tired quickly, and the doctors were monitoring his blood pressure and heart.

PTSD episodes are cruel in their ripple effect; it’s not just the mind that feels the shock.

On the day the charges were announced, Andrea and Gus visited him.

I stepped into his room a few minutes after they arrived, balancing a tray with coffee and a small cup of vanilla pudding he’d pretended not to like the day before.

“And now they’re all over the news,” Leo was saying, voice rough but steady.

“I’ve got strangers yelling at kids they’ve never met on my behalf. Feels strange.”

Gus shrugged, arms crossed loosely over his chest.

“Some of us yelled on our own behalf for a long time and nobody listened,” he said. “Maybe that’s part of why this took off. People know they look bad if they ignore a veteran on camera. Makes them feel righteous to get mad.”

Andrea glanced at me gratefully when I set the tray down.

“The prosecutor wants to meet with you,” she told Leo gently. “They’re considering a plea deal that would include restitution and mandatory service at Second Tour House. They’d like your input. Not because you control what happens, but because your voice matters.”

Leo poked at the pudding with his spoon.

“Restitution? What are they going to pay me with?” he asked. “Their allowance?”

He sighed. “I’m not laughing because it’s funny. I just never pictured myself in this kind of drama at my age.”

“Leo,” I said, pulling up a chair. “They’re also talking about you speaking at the sentencing hearing, if it comes to that. You don’t have to. But if you want to say something, that’s an option.”

He looked out the window, where a thin tree bent in the wind without breaking.

“My father dreamed I’d give some kind of speech one day,” he said. “He probably thought it would be at a wedding, not in a courtroom.”

Andrea leaned forward.

“You don’t owe anyone a speech,” she reminded him. “You owe yourself rest and respect. Everything else is extra.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“I keep thinking about their faces,” he said finally. “Not on the video. At the meeting. That tall one—what’s his name?”

“Chase,” I said.

“Yeah. Chase,” Leo repeated.

“He looked like a kid who finally realized the stove is hot after touching it three times. The other two looked like they’d known it was hot the whole time and touched it anyway because he dared them. I’ve seen that dynamic before.”

“In the service?” Gus asked.

“In life,” Leo replied.

“Out there too, sure, but not just there. One loud voice, two quiet ones. Sometimes you can reach the quiet ones if you get to them before they harden up.”

Later that day, while Leo rested, I found myself standing outside a law office downtown.

The prosecutor had asked me to stop by to give additional detail about what I’d heard at the scene and to talk about the impact the incident had on Leo and on the community.

Inside, the waiting area was all polished wood and potted plants without dust.

A framed motivational quote on the wall talked about justice being blind; I wondered if they ever considered whether justice had good hearing.

Assistant District Attorney Hall met me in a conference room with a notepad and an expression that balanced empathy with professional distance.

“Ms. Ortiz, thank you for coming,” she said. “I know this has been a lot.”

“It has,” I agreed. “But it’s been worse for Leo.”

Hall nodded.

“We want to handle this in a way that recognizes the real harm done while also acknowledging that these are young offenders with no prior record,” she said. “We’re preparing a plea offer that would include supervised probation, a period of confinement in a juvenile facility, mandatory counseling, and structured community service at Second Tour House. We’re also recommending they attend and participate in a victim impact panel.”

“You mean they’d have to listen to Leo talk about what happened,” I said.

“And other veterans, and possibly other people harmed by online cruelty,” she added.

“Nothing in this is about humiliating them. It’s about making them sit with the consequences long enough for them to sink in. We believe that’s more effective than a purely punitive approach.”

“Some people are going to say that’s too soft,” I warned her.

“They’re already saying it.”

She smiled wryly.

“Others are saying it’s too harsh,” she said. “If we’ve made everyone a little unhappy, we might be close to the right balance.”

I thought of the mother at the meeting, voice shaking as she begged the room not to destroy her son.

I thought of Leo on the sidewalk, curled in on himself while laughter floated above him.

Balance felt like a fragile word to rest on.

“Will Leo have a say?” I asked.

“He’ll have a voice,” Hall corrected kindly. “The decision is ultimately ours and the court’s, but his wishes will carry weight. If he tells us he never wants to see them again, we won’t force a face-to-face. If he wants to speak, the judge will likely allow it.”

When I left the office, the sun was low, throwing long shadows across the sidewalk.

A group of middle schoolers walked past, each with a phone in hand, screens glowing.

They laughed together, showing each other something, then one of them slipped their phone into a pocket to help an older woman with her groceries up the steps.

It was such a small act that most people would have missed it.

I didn’t.

That evening, back at the hospital, I told Leo about the proposed plea.

He listened without interrupting, fingers tapping a slow rhythm on the blanket.

When I finished, he sighed and looked at the ceiling.

“I don’t want to be the reason anybody’s child spends their life trapped in that one worst moment,” he said. “But I also don’t want them to forget that moment so fast they learn nothing from it.”

“You don’t have to decide right now,” I reminded him.

“You can take time. Talk to your family. Talk to Gus and Andrea. Talk to yourself.”

He chuckled softly.

“I’ve been talking to myself for years,” he said. “He’s not always the best listener, but I’ll give it another shot.”

A week later, when he felt strong enough to sit up for more than half an hour, Leo asked Andrea to bring him paper and a pen.

Not a laptop. Not a phone.

He wrote slowly, every curve of ink a little uneven from the tremor in his hand, but he didn’t stop until he had filled three pages.

When he finished, he handed the papers to me.

“Will you read it?” he asked.

It was a letter addressed to the court, to the boys, and to the town.

It was not gentle.

It did not excuse.

But it also did not call for endless punishment. It asked for something harder: that they look at him not as a symbol, not as a clip, but as a man, and that they allow him to see them the same way in return.

At the end, his handwriting grew even shakier, but the words were clear.

“If they are willing to carry part of what they put on my shoulders that day,” he wrote, “then I am willing to stand in that courtroom and carry my cane there myself. I have stood on worse floors.”

When I looked up from the letter, Leo was watching me.

“So,” he said. “I guess that means I’m going to court.”

PART 6 – The Floor He Chose to Stand On

The courthouse steps were steeper than they looked.

Leo took them one at a time, his cane landing first, his weight following like it had to think about it.

Gus walked on one side, Andrea on the other, and I followed half a step behind, spotting him the way we spot patients who swear they don’t need help.

The fall air had a bite to it, sharp enough to make my lungs feel too small.

Inside, the hallway hummed with low conversation and hard shoes on tile.

There were reporters, but fewer than the internet frenzy might have suggested, and no cameras allowed past a certain point.

A clerk pointed us toward the courtroom with the practiced efficiency of someone who did this every day.

It felt strange to walk toward a door knowing a moment from your life behind it had already been replayed millions of times.

The courtroom itself was less dramatic than television shows.

Wood paneling, flags, a raised bench for the judge, stiff pew-style seating for the rest of us.

On one side sat the prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Hall, with a neat stack of files.

On the other sat the defense attorneys and the three boys, in collared shirts that looked like they still had the tags on.

Chase glanced up as we entered.

For a second, his eyes met Leo’s, then dropped immediately to his folded hands.

Tyler stared at the table in front of him, jaw clenched, a single muscle jumping near his temple.

Jaden’s gaze flicked nervously between his mother, the floor, and the door, as if he wasn’t entirely convinced he wouldn’t bolt.

We sat in the row behind the prosecutor’s table.

Leo adjusted himself carefully on the hard bench, cane leaning against his knee.

His daughter, Emma, slid in beside him, squeezing his hand so tightly I could see the pale outline of her fingers.

On the other side, Gus sat upright, shoulders squared, as if he were back in a briefing.

The judge entered, robes swishing, and everyone stood.

When we sat again, the air felt charged, like the moment before a storm when the world holds its breath.

“This is the matter of State versus Chase Miller, Tyler Grant, and Jaden Ross,” the judge said.

“We are here today to consider a proposed plea agreement and, if accepted, to hear victim impact statements before sentencing. I expect decorum and respect from everyone in this room.”

ADA Hall rose first, summarizing the case in calm, precise language.

She described the planned prank, the fake blast, the panic episode, the failure to render aid.

She referenced the video without playing it yet, noting that “the defendants chose to broadcast a medical emergency in real time to an audience rather than immediately seek help.”

The defense attorneys followed with their own comments, choosing their words carefully.

They spoke of youth, of poor judgment, of “a culture of constant filming” that blurred lines their clients should have seen clearly.

They didn’t deny what happened; instead, they argued that the plea agreement – with its mix of legal consequence and community service – offered the best path forward for everyone.

As they spoke, I watched the boys’ faces.

Chase shifted in his chair, swallowing hard.

He looked less like the confident streamer from the video and more like a kid who’d stayed out too late and was trying to guess how deep the trouble would go.

Tyler’s eyes were red-rimmed, like he hadn’t been sleeping much, and Jaden kept pressing his lips together until they turned white.

When it was time to play the video, the bailiff wheeled in a monitor and set it up facing the judge and jury box.

The screen flickered, then showed the familiar sidewalk, the familiar older man walking with a grocery bag, the familiar split second when sound became a weapon.

I’d seen this clip too many times.

Still, my stomach clenched as Leo’s body folded to the pavement.

The courtroom, like every room before it, reacted in tiny ways – a sharp inhale here, a hand tightened on a knee there, a muscle in the judge’s cheek twitching.

When Chase’s voice floated through the speakers, bright and excited, I heard someone in the back mutter under their breath.

The judge glanced up sharply and the room fell quiet again.

The line “cut the setup, just keep the part where he drops” landed with more weight in that space than any caption online had given it.

When the screen went black, the judge exhaled slowly.

“I have seen many things in this courtroom,” he said. “I have rarely seen such a stark example of how technology can magnify harm when empathy is missing.”

He turned to the boys.

“Young men, you have each signed a plea agreement acknowledging your role in this incident,” he said. “Before I decide whether to accept that agreement and impose sentence, Mr. Parker has requested the opportunity to address the court. You have the obligation to listen. He has the right to be heard.”

Leo’s hand tightened on his cane.

He nodded once when the judge looked toward him, then began the slow process of standing.

I watched the tremor in his legs, the way his shoulders squared once he was fully upright, as if some internal switch had flipped from patient to soldier.

Gus moved as if to help him, but Leo shook his head.

“I got it,” he murmured. “If I’m going to talk about standing up, I should probably do it while I’m actually standing.”

The judge gave him permission to approach the podium.

It seemed farther away than it had when the lawyers used it.

Each step Leo took was careful, measured, the rubber tip of his cane making soft sounds against the floor that somehow echoed anyway.

When he reached the microphone, he adjusted it with unsteady hands.

He didn’t look at the judge right away.

He looked at the three boys instead.

“My name is Leonard Parker,” he began, voice low but clear.

“Most people just call me Leo. Some still call me Sergeant, but that was a long time ago.”

He paused, breathing once, slow and deliberate, as if testing how much his lungs could hold.

“I’m here because of a video,” he continued. “But that video doesn’t start where you all think it does.”

He let that hang for a moment, letting the room lean in.

Then he began to tell them where, in his mind, it had really started.

PART 7 – The Speech That Went Beyond the Room

“The video you all saw starts on a sidewalk,” Leo said.

“For me, it starts on a road that doesn’t exist on any map you’ll download. It starts with heat and noise and sand in places sand shouldn’t be. It starts with twenty-year-old kids being told to walk down streets where any sound might be the last one they hear.”

He didn’t raise his voice.

He didn’t need to.

The courtroom had gone so quiet that even his breaths felt like part of the testimony.

“I’m not here to give you a war story,” he continued.

“I’m not going to tell you what I saw, what I did, what I lost. Some of that doesn’t belong in this room, and some of it doesn’t belong anywhere but in the past. But I need you to understand something: my body doesn’t know the difference between that road and that sidewalk sometimes. It hears a certain sound and it says, ‘We’re back there. Get down or die.’”

He glanced at the boys, at their parents, at the cluster of students in the gallery.

“PTSD isn’t always a big dramatic scene,” he said.

“Most days, it’s background noise. It’s forgotten appointments and restless nights and scanning exits in restaurants. It’s looking fine on the outside while your brain whispers, ‘Be ready.’ It’s not a joke. It’s not content. It’s not a special effect.”

Emma wiped at her eyes with the back of her hand.

Gus stared fixedly at the table, jaw tight.

I felt my own heart pounding in sync with Leo’s words, every syllable scraping something old and raw inside me.

“That day at the shopping center,” he went on, “I was thinking about whether the milk would go on sale next week. I was thinking about whether my grandson would remember to call me for his test results. I heard a loud bang behind me, and my legs didn’t politely ask what it was. They put me on the ground. My arms put my hands over my head. My nervous system did what it was trained to do. It tried to keep me alive.”

He swallowed, throat working.

“And while that was happening,” he said, “three young men stood over me and decided it was something to broadcast. They weren’t terrorists. They weren’t enemies. They were kids from a town like this one. They saw a chance for views and they took it.”

He tapped the podium lightly with one hand.

“I want to be very clear,” he said. “What they did was cruel. It was thoughtless and dangerous and it could have ended a lot worse. They need to be held accountable. They need consequences that stick. But if all we do is throw them in a box and throw away the key, then we will have learned nothing from any of this except how to hurt each other back.”

The judge’s expression softened almost imperceptibly.

ADA Hall looked down at her notes, blinking hard.

Even one of the defense attorneys cleared his throat and shifted in his chair.

“I’ve seen what happens when people come home and feel like they’re only good for one thing,” Leo said.

“I’ve seen what happens when young people make one terrible choice and are told that’s all they’ll ever be. My own head tells me those kinds of lies sometimes. I don’t want to be another voice adding to that chorus.”

He looked at Chase directly now.

“You did something unforgivable that day,” he said.

“You took a man’s worst moment and tried to make it a punchline. You tried to erase your part in causing it. You treated me like I was less than human. But I’m still here. I remember every second you probably wish had disappeared. And I am choosing to do something you didn’t choose in that moment. I am seeing you as a person.”

Chase’s chin trembled.

His mother reached for his hand and missed because he didn’t move.

Tyler blinked rapidly, while Jaden’s shoulders shook once before he bit it back.

“I don’t want you walking away from this thinking all veterans are out for your blood,” Leo continued.

“I don’t want you walking away thinking you’re monsters with no way back. I also don’t want you walking away thinking this was just a bad day that doesn’t matter. So here is what I’m asking for.”

He turned slightly toward the judge, but kept his voice aimed at the whole room.

“I support a sentence that includes time in a juvenile facility,” he said.

“I support probation, counseling, and restitution as the law allows. But I also ask that they be required to spend time at places like Second Tour House. Not for a photo op. Not for a week. For as long as it takes to see that people like me are not props for their cameras.”

He let his hand rest flat on the podium.

“I am willing to stand in the same room with them again,” he said.

“I am willing to tell this story until my voice gets hoarse if it means one kid in one hallway somewhere puts their phone down and reaches out a hand instead. I forgive them. Not because what they did was small, but because carrying hatred is heavy, and I’ve carried enough weight.”

He took one last breath, in and out.

“And I want them to carry something too,” he finished. “Not just a record. A responsibility. Every time they see someone fall, I want them to remember my face on that sidewalk and ask themselves, ‘Am I going to film this, or am I going to help?’ If this court can help make that question part of their sentence, then whatever happened to me that day won’t just be cruelty. It will be a turning point.”

When he stepped back from the podium, his hands shook more than when he’d stepped up.

He gripped his cane harder, legs wobbling for a second before Gus rose halfway to offer an arm.

Leo accepted it this time, letting his friend steady him on the walk back to his seat.

The judge cleared his throat twice before speaking.

“Mr. Parker,” he said, “this court thanks you for your courage and your clarity. Your statement will be taken deeply into account as I consider sentence. We will reconvene after a brief recess.”

The gavel tapped, and people began to breathe again.

As Leo sat, his color drained a little, and he pressed his hand against his chest.

“Just a little tired,” he said when Emma fussed over him. “I haven’t given a speech like that since they made me talk at my cousin’s wedding.”

In the hallway during recess, someone with more enthusiasm than discretion held their phone a little too high, angling for a shot through the doors before a bailiff stopped them.

There were rules about filming in court, but rules and reality don’t always match.

Before the day was done, a grainy recording of Leo’s speech – captured from the back row and posted anonymously – began to seep onto the same platforms that had once hosted his panic.

This time, the captions were different.

“This veteran just changed how I’ll use my phone,” one read.

Another said, “Watch this before you post your next ‘prank.’”

By the time the judge returned and accepted the plea agreements, millions of people had already watched Leo stand and speak.

They shared clips in group chats and classrooms, argued about forgiveness versus punishment, and wrote long comments about relatives who had served and come home different.

None of that changed what needed to happen next.

The law still had to speak in its own language.

As the judge began to outline the terms of the sentence, Leo leaned a little heavier into his cane.

His forehead shone with a fine sheen of sweat.

By the time the judge said, “You will report to the juvenile facility on—” Leo’s eyes fluttered, and his body tilted.

I was already moving as he slumped sideways.

Emma caught his shoulder, I caught his arm, and Gus braced his back, turning a fall into more of a slide.

The courtroom gasped, but training kicked in before panic could.

“Call the medics,” I heard myself say.

“Now.”

PART 8 – Sentences Written in Different Ink

The paramedics who arrived in the courtroom knew Leo by name.

They had been the same crew who’d responded at the shopping center, the same crew who’d watched the video replay in training sessions that followed.

They moved with professional calm, checking his pulse, his blood pressure, his pupils, talking to him in low, reassuring voices.

“Just pushed his body a little hard today,” one of them said quietly after a quick evaluation.

“We’ll take him to the hospital and run tests, but he’s responsive. Likely a combination of stress and exertion. He’s earned a nap.”

As they wheeled him out, Leo lifted his hand weakly.

“Don’t you dare stop because of me,” he muttered.

“If I passed out every time a judge talked, we’d never get anything done.”

The judge called another recess, longer this time.

The boys sat frozen at the defense table, faces pale.

For a few minutes, they weren’t defendants or content creators or cautionary tales. They were just teenagers watching an older man, whose worst moment they’d turned into a spectacle, be carried out on a stretcher.

When court resumed the next afternoon, Leo was not present.

He had insisted on calling in to listen by phone, but his doctors put a firm stop to that.

Emma came instead, letter in hand, the one he’d written before the hearing.

The judge held it up briefly.

“Mr. Parker has authorized me to share portions of his written statement,” he said. “I will not read it all into the record, but I will say this: he asks this court to balance accountability with the possibility of change. He asks that we remember he is more than a victim, and that the defendants are more than this moment.”

He looked at the boys.

“In light of the plea agreements and Mr. Parker’s wishes, I hereby sentence you as follows,” he said.

For Chase, as the primary instigator, the sentence was the heaviest.

Six months in a juvenile facility, followed by two years of supervised probation.

Mandatory individual and group counseling focused on empathy, responsibility, and media use.

Five hundred hours of community service at organizations serving veterans and trauma survivors, including Second Tour House, to be completed over no less than two years.

Tyler’s sentence was similar but slightly reduced, reflecting his role as a follower rather than leader.

Three months in juvenile detention, two years of probation, four hundred hours of service.

Additional requirement: completing a supervised media ethics program before being allowed to post to any public platform again.

For Jaden, whose hesitation and later cooperation with investigators had been noted, there was no detention time, but a longer period of probation and three hundred hours of service.

The judge emphasized that his relative leniency was “a response to your actions after the harm, not a denial of the harm itself.”

“For all three of you,” the judge continued, “you are prohibited from monetizing this incident in any way, now or in the future. No interviews for pay, no ‘apology’ channels built on this story, no merchandise, no documentaries about your own pain unless and until you have spent more years serving others than you spent chasing views. If in doubt, ask your probation officer before you post, speak, or sign anything.”

He leaned forward, hands folded.

“I cannot make the internet forget,” he said. “Your names may always be associated with this. But I can ensure that what follows those names includes the work you will now have to do. Whether you let that work change you is up to you.”

He invited each of them to stand.

Chase’s knees shook.

“I’m sorry,” he said, voice thin. “I know that doesn’t fix anything. I thought I could control the story. I thought it would make me somebody. I didn’t think about who I was making him into. I just… I’m sorry.”

Tyler spoke next.

“I edited the clip,” he said. “I’m the one who cut out the part where we set it up. I told myself it wasn’t lying if people didn’t see it. I don’t know how to undo that, but I know I don’t ever want to see someone on a screen and forget there’s a whole life around that moment.”

Jaden’s voice cracked when he talked.

“My brother is in basic training,” he said. “I kept picturing his face instead of Mr. Parker’s and I hate that it took that for me to feel it properly. I volunteer at the hospital now. When someone falls, I leave my phone in my pocket. It’s not enough. But it’s a start.”

The judge listened, then nodded.

“Your words are noted,” he said. “From this point on, your actions will speak louder.”

Outside the courthouse, the reaction was immediate and chaotic.

Some groups held signs demanding harsher punishment, arguing that “if he had died, this would be different.”

Others praised Leo’s mercy, calling him “the man who remembered we’re all still human.”

Online, the speech clip continued to spread.

Teachers used it in media literacy lessons.

Veterans shared it with captions about feeling seen.

Teenagers stitched it with their own faces, some defensive, some ashamed, some genuinely moved.

At Second Tour House, life went on in slow, ordinary ways.

Coffee brewed too strong in the mornings, newspapers were argued over and eventually read, chairs were claimed and re-claimed.

On the bulletin board, under flyers for support groups and potlucks, Andrea pinned a new sign: “Volunteer Orientation – Mandatory for court-ordered participants, optional for everyone else.”

The first day the boys showed up, they stood awkwardly in the doorway, supervised by a probation officer who seemed content to lean against the porch railing and watch.

Chase wore a plain T-shirt and jeans, his usual swagger folded away somewhere.

Tyler clutched a notebook, as if unsure whether he was allowed to open it.

Jaden carried a box of canned goods like he was hoping the weight would justify his presence.

Gus met them there, arms crossed.

“You’re not here to entertain anyone,” he said. “You’re not here to be entertained either. You’re here to work. You’ll move chairs, set up tables, listen more than you talk. If you’re lucky, somebody might eventually decide to tell you something worth hearing.”

They nodded, faces sober.

Inside, some of the veterans crossed their arms, wary.

Others watched with a detached curiosity, willing to let time decide what they felt.

As weeks turned into months, the sentences began to write themselves in different ink than the court documents.

In missed basketball games so Jaden could drive an older man to a doctor’s appointment.

In Saturdays where Tyler sat with a recorder, capturing stories for an oral history project under Andrea’s supervision, learning to ask “Are you okay sharing this?” before hitting the button.

In the way Chase scrubbed tables, set up chairs, and, eventually, sat at the edge of a circle instead of outside the room.

Not every day was profound.

Some days were just coffee refills and card games.

But slowly, the weight of what they’d done began to share space with the weight of what they were trying, imperfectly, to do now.

PART 9 – The Slow Change No One Clips

Change doesn’t trend.

It rarely comes with dramatic music or perfect lighting.

Most of the time, it looks like the same hallway you walked down yesterday, with one less cruel joke and one more quiet decision nobody writes a headline about.

A year after the sentencing, Second Tour House looked mostly the same.

The ramp still creaked in cold weather, the flag on the porch still frayed a little at the edges, the coffee still tasted vaguely like melted pennies.

But if you sat in the common room long enough, you could feel small shifts.

A younger veteran named Malik, who had barely spoken above a mutter his first month there, now ran a weekly game night.

He joked about the rules, trash-talked about card hands, and escorted newcomers away from the door when they looked like they were about to bolt.

He had once told Tyler, quietly, that watching Leo speak in court had been the first time he believed someone older truly understood what his panic attacks felt like.

Tyler, for his part, had become the unofficial archivist.

With Andrea’s guidance and consent forms in triplicate, he recorded stories from anyone willing to share.

He learned to keep his camera angle steady, his questions gentle, his focus on the person rather than on clever edits.

The videos never went on his old public channel. They lived instead on a password-protected site for families and veterans who wanted to remember.

Jaden split his time between the House and the hospital.

He volunteered in the emergency department where I worked, stocking supplies, grabbing blankets, fetching water.

The first time he helped me steady a patient who had collapsed in the waiting room, his hands shook.

The second time, they shook less.

“My brother says emergencies don’t care if you’re ready,” he told me once, after we’d both washed our hands for the third time that hour.

“I’m trying to be ready now. Not with my phone. With my hands.”

Chase took longer to find a path.

After his release from the juvenile facility, he had to repeat a school year, faced whispers in hallways, watched college brochures disappear from his mailbox.

For a while, he avoided any place where his name might be recognized.

But the terms of his probation were clear.

He had to show up at Second Tour House.

He had to attend counseling.

He had to participate in victim impact panels, not as a star, but as an example.

One evening, after a meeting where he had stumbled his way through an apology to a group of high school students, he slumped on the back steps of the House, elbows on his knees.

I stepped outside to get a breath of air and found him there, staring at his hands.

“They still send me clips,” he said without preamble.

“People from other towns, other schools, digging up the video, sending it to my messages like they just found it. I blocked the apps they used to watch me on. Doesn’t matter. It’s still out there.”

I sat down beside him, keeping a respectful distance.

“Some things don’t come down,” I said. “Even when they should.”

He nodded, jaw working.

“I used to think the worst thing that could happen was being ignored online,” he said. “Now I know worse. It’s being remembered for the worst thirty seconds of yourself, over and over, by strangers who don’t care if you’re trying to be better.”

“Are you trying?” I asked, not unkindly.

He nodded again.

“I used to measure my day in views,” he said. “Now it’s more like… did I make it through a shift without wanting to hide? Did I hear a veteran’s story and listen instead of thinking what angle would play best? Did I leave my phone in my locker when I walked past a car crash instead of thinking ‘first one to post wins’?”

He huffed out a humorless laugh.

“None of that is impressive enough to post,” he added. “But maybe that’s the point.”

Meanwhile, Leo’s life had shifted into a new rhythm.

His health scare after court had given his doctors leverage to insist on better pacing.

He still came to Second Tour House, though he took the ramp more slowly, and he still made time for his grandchildren on Sundays.

He also started visiting schools.

The first time he spoke at a high school assembly, he asked me to come along.

The auditorium felt like the town hall meeting all over again, rows of teenagers with varying degrees of interest and fidgeting.

Teachers patrolled the aisles, ready to confiscate phones or at least glare at them.

Leo didn’t open with the video.

He opened with a photograph.

On the projector behind him, he put up a picture of himself on a camping trip, grinning at the camera, marshmallow on a stick, one of his grandkids climbing his back.

“This is me,” he said.

“Not on a sidewalk, not in a clip, not at my worst. Just me, on a day when the loudest thing I heard was my grandson laughing because the marshmallow fell in the fire. When you think about veterans, I want you to remember we have these days too.”

Then he showed a still from the video, taken at the moment before he fell.

He spoke about PTSD, about reflexes, about training that didn’t always come with an off switch.

He did not show the clip of his collapse.

He refused to replay his own pain for them.

“You don’t need to watch me hit the ground to understand this,” he said.

“You just need to remember that the man you see for ten seconds has sixty-nine years wrapped around those seconds. When you film someone, you’re capturing one frame of a whole life. Ask yourself what you’re doing with it.”

At the end of the talk, he said the line that had begun to follow him around, the one people quoted and stitched and wrote on posters.

“When you see someone fall,” he told the students, “you have exactly one second to decide what kind of person you are. Do you reach for your phone, or do you reach for them?”

In the back row, a girl lowered her phone and put it in her backpack.

Her friend followed.

One boy kept recording for a moment longer, then stopped, cheeks red, as if he’d felt a spotlight swing his way.

After that assembly, the district asked Leo to speak at more schools.

Other towns called.

Sometimes he went. Sometimes he sent a video of himself speaking directly to the students, carefully recorded with Tyler’s help at Second Tour House, eyes on the lens like he could see each kid behind it.

A second year passed.

Some of the heat of the original viral outrage cooled.

New scandals, new clips, new bad decisions took its place in the ever-hungry feeds.

But in pockets – in classrooms, in living rooms, in veteran centers – Leo’s words kept playing.

By then, the boys were nearing the end of their probation.

Jaden had started training as an EMT, following the paramedics from call to call, learning how to manage his own adrenaline.

Tyler had been accepted into a community college program for social work and media, hoping to use his skills in a more careful way.

Chase worked at a warehouse nights and volunteered at the House on weekends, trying to build something quieter than an online following.

When their probation officers told them they would be required to attend one last mandatory event – a district-wide assembly where Leo would speak to multiple high schools at once – none of them argued.

They just asked one question.

“Will we have to talk too?”

“Yes,” their officers said.

“If you’re willing.”

They were.

PART 10 – What We Choose to Film

The gymnasium smelled like floor polish and adolescence.

Bleachers groaned under the weight of hundreds of students, teachers clustered near the aisles, the principal fiddling with a microphone that squealed before settling.

Up on the stage, three chairs waited beside a podium and a screen.

I stood near the side with Andrea, watching the crowd settle.

We’d both seen this before: the mix of boredom, curiosity, and restless energy that comes when you tell teenagers they have to listen to adults talk about “serious matters.”

Leo walked carefully to his chair, the cane in his hand more a tool than a crutch now.

He wore a simple button-down shirt, his “Veteran” cap held loosely instead of on his head.

The three young men took their seats beside him, not in handcuffs, not in shame, but in something closer to uneasy honesty.

When the principal finished his introductions, he stepped back and let Leo have the microphone.

The speech he gave was familiar but never rote.

He talked about context, about nerves that don’t know when the war is over, about the difference between witnessing and exploiting.

At the end, his voice softened, the way it always did when he reached the line that had become his signature.

“I can’t control everything you see on your screens,” he said.

“I can’t keep you from watching things that hurt you, or from being watched when you’re hurting. But I can say this: when you see someone fall, you have exactly one second to decide what kind of person you are. Do you reach for your phone, or do you reach for them?”

He handed the microphone to the moderator, who then turned to the three young men beside him.

“Chase, would you like to share something?” she asked.

He stood slowly, fingers curling around the mic stand.

“I used to think you weren’t real unless someone else could see you,” he said, looking at the sea of faces.

“If I had a bad day and didn’t post about it, it felt like it didn’t count. If I did something risky or cruel and it got a lot of views, I told myself it meant people liked me.”

He swallowed, cheeks reddening.

“When we did what we did to Mr. Parker, I thought I could edit out the parts that made me look bad,” he continued.

“I thought I could control what people saw. I was wrong. I hurt him, and I hurt a lot of people who recognized themselves in what happened, and I can’t undo that. The only thing I can do now is make different choices with the seconds I get.”

Tyler spoke next, his voice quieter but steady.

“I used to think my job was to make everything look interesting,” he said.

“Now I know some things deserve to be witnessed without being turned into a show. When I record veterans now, it’s because they asked me to. When someone falls in front of me, I don’t ask myself if it would make a good clip. I ask where the nearest first aid kit is.”

There was a ripple of nervous laughter at that, softer and less cruel than most.

He let it pass, then added, “If you’re someone like me, who loves cameras and stories, just remember that the person you’re filming has to live with that moment long after your video scrolls away. Ask. Think. Then decide.”

Finally, Jaden took the mic.

He looked toward the back of the gym, where his brother, now in uniform, sat with other service members invited for the day.

“I’ve pushed a stretcher with someone on it who might not make it,” he said.

“I’ve watched families’ faces when we tell them we don’t know yet if their person is going to be okay. I’ve also watched people stop to help before they know anyone’s watching. Those are the people I want to be like now.”

He looked out at the students, meeting their eyes.

“If you’re ever there when someone goes down,” he said, “remember that you might be the only one standing close enough to do something. Don’t waste that second proving you were there. Prove it by what you do, not what you post.”

The moderator thanked them and opened the floor for questions.

A few students asked practical things about PTSD and how to help someone having a panic attack.

Others asked the harder questions about forgiveness and whether the three young men forgave themselves.

“We’re working on it,” Chase said, and the honesty in his voice was more powerful than any polished speech.

When the assembly ended, there was the usual scramble toward the exits.

Some students pulled out phones in the parking lot, recording their own reactions, their own takes.

That was inevitable.

Stories grow tendrils.

But in one corner of the gym, something small happened that nobody filmed.

A janitor had been folding up extra chairs near the bleachers when his foot caught on a stack and he stumbled, arms windmilling.

He didn’t fall hard, just dropped to one knee.

Almost instantly, two students broke off from their group and hurried over, one offering a hand, the other steadying the chairs.

“Are you okay?” one of them asked.

The janitor chuckled, embarrassed but grateful, and let them help him up.

Out of habit, my eyes flicked to see if anyone had their phone out aimed at him.

A few kids glanced over, then went back to what they were doing.

No one lifted a camera.

Leo stood beside me, watching the same small scene.

“Not a bad ratio,” he murmured.

“One stumble, two helpers, zero cameramen.”

“Progress,” I said.

He put his cap back on, adjusting the brim.

“You know, when this started, I was so angry I could taste it,” he admitted.

“I still get flashes of that sidewalk when I close my eyes sometimes. But when I see things like that? The hand going out first? It makes the weight a little lighter.”

Andrea joined us, nodding toward the three young men talking quietly with a group of students near the stage.

“They’ll never be anonymous again,” she said. “But maybe that’s not entirely a curse. Every time someone recognizes them, they’ll have to decide, again, who they want to be now. That kind of accountability doesn’t end when the probation does.”

Later that afternoon, back at Second Tour House, the common room was full.

A cake sat on the table with uneven frosting that read “Thank you, Leo” in wobbly letters.

Malik had insisted on baking it himself, which explained the leaning tower effect on one side.

Leo rolled his eyes when he saw it but his smile gave him away.

“You all know I’m not dying, right?” he grumbled. “You don’t have to throw me a farewell party every time I speak at a school.”

“It’s not a farewell party,” Andrea said. “It’s a ‘we’re glad you keep coming back’ party.”

We gathered for a group photo, someone setting a timer on a camera propped up on a bookshelf.

Leo sat in the center, grandkids squished on either side of him, veterans clustered around, staff threaded through.

The three young men stood in the back row, not hiding, not posing, just present.

When the shutter clicked, nobody yelled for retakes.

Nobody rushed to grab the camera to post the picture with a clever caption.

The photo would end up printed and taped to the bulletin board, edges curling over time, colors fading slowly as the years went on.

I looked at it later, alone in the quiet room.

A cựu binh who’d survived more than one kind of blast.

A nurse who had once held her father’s hand in a different hospital room.

Three young men whose worst moment had nearly frozen them there forever, now in the middle of writing new ones.

A roomful of people choosing, over and over, to see each other as more than clips.

I thought about all the seconds that had passed between that fake explosion and this soft, ordinary afternoon.

The choices made in each one.

The times we’d failed.

The times we’d managed, just barely, to reach for each other instead of the nearest lens.

Somewhere, someone was still filming the wrong thing.

Somewhere, a new cruel prank was being planned.

This story did not fix the world.

But here, in this house with its chipped mug collection and frayed flag, there was a different kind of viral spread.

Small acts of attention.