Part 1 – The Call I Let Go to Voicemail

The night my veteran father died alone in an emergency room, a nurse asked if I wanted to come say goodbye, and I said no, because I’d already buried him in my heart years earlier. I hung up before she could say the word “sorry.”

The caller ID just said “Unknown Hospital Number,” and for a second I considered letting it go to voicemail like every other number I didn’t recognize. When I answered, a soft, careful voice asked, “Is this Emily Harper?” and my stomach already knew something was wrong. “I’m calling about a patient, Daniel Harper,” she said, and the room felt smaller. “He listed you as his emergency contact.”

My father had never been there in any emergency of mine, but apparently I was still his. The nurse explained he had collapsed on a bus and had been brought in by ambulance. She told me he didn’t suffer for long, that they had done what they could. Then she asked if I wanted to come in, to see him, to sign the paperwork, to have one last moment.

I stared at the wall clock above my kitchen sink and listened to my son’s cartoon murmuring from the living room. “No,” I said, shocking even myself with how steady my voice sounded. “I’m not his family anymore.” The silence on the other end stretched so long I could hear my own heartbeat, then the nurse whispered that someone still needed to identify him. I told her they would have to find someone else and ended the call.

The truth was, I had already had a funeral for my father in my head. It happened the night he threw a chair across our tiny living room because a firework went off outside and his mind snapped back to a desert halfway across the world. I was fifteen, hiding behind the couch, and he was standing there in his old uniform pants, shaking and sobbing and smelling like cheap whiskey. That was the night I decided I would never let his war spill over into my life again.

People love to thank veterans for their service in the grocery store and on certain holidays. They don’t see the way those same veterans pace the hallway at 3 a.m., or how their kids learn to read the weather in their fathers’ eyes. My dad served as a medic overseas before I was born, came home with scars he wouldn’t talk about, and a temper that arrived without warning. My mother lasted nine years, then packed two suitcases and said, “I can’t raise both of you,” before walking out.

The last time I saw him while he was still “alive” to me, he showed up unannounced at the apartment I shared with my fiancé. He was sober, hands shaking, holding a gift bag with tissue paper sticking out of the top. I didn’t even look inside. I told him he’d missed too many recitals, too many birthdays, too many chances to choose me over a bottle or a memory. He said he was getting help, that he was going to a group at the center on Thursdays. I told him it was too late, and the words “You’re dead to me” left my mouth before I could stop them.

So when the nurse called years later, I reminded myself that I had meant it. I cleaned the kitchen counter, packed my son’s lunch for school, and tried to act like I hadn’t just declined to claim my own father’s body. Only once, rinsing a knife in the sink, did my hand tremble enough to make it slip, and even then I told myself it was just because I was tired from too many night shifts at the hospital.

Three days passed before the knock at my door came. It was a heavy knock, the kind that sounds like it knows it’s not welcome. When I opened the door, a man filled the frame, tall and broad, with a gray beard that fell to his chest and a faded army jacket that had seen better days. A metal brace peeked from beneath his left pant leg, and he leaned slightly on a worn wooden cane.

“Emily?” he asked, his voice low and rough, like he’d spent years shouting over engines or explosions. “I’m Reggie. I served with your dad, back before either of us knew what the word ‘after’ would feel like.” He shifted his weight and looked almost embarrassed. “They called the center when you didn’t come in. They said they needed next of kin. That’s you, whether you like it or not.”

“I told them I wasn’t coming,” I said, keeping the door half-closed between us. “They shouldn’t have dragged you into this.” My son laughed at something on the TV behind me, and I saw Reggie’s eyes flick toward the sound, softening for a second. Then he met my gaze again and shook his head.

“Doc doesn’t have anyone else,” he said quietly, using the nickname I hadn’t heard in years. “No parents, no siblings, no one. Just you. He always said that, like it was a good thing.” He took a breath. “They can’t release him, or his things, without family. He deserves at least that much. You deserve to know where he spent his last years.”

The phrase “his things” made my chest tighten in a way I didn’t like. I imagined dirty clothes, old pill bottles, maybe a mattress on the floor of some halfway house. “Can’t someone from the center sign whatever needs signing?” I asked. “You knew him. You were…there.”

Reggie shook his head again. “We’re brothers in arms, not on paper. There’s a difference, whether we like it or not. Please, Emily. It won’t take long. Just…come see.” He didn’t push the door, didn’t raise his voice. He just stood there, a tired man carrying someone else’s last request.

In the end, what made me grab my keys wasn’t love or duty. It was the thought of some stranger throwing my father into a metal drawer and labeling him “unclaimed.” I told my neighbor I’d be gone a few hours and asked her to watch my son. Then I followed Reggie out to his truck, the silence between us thick enough to choke on.

The county morgue was colder than I expected, all white walls and metal surfaces and the faint smell of disinfectant that somehow still couldn’t cover the truth of what happened there. A technician led us down a hallway and pulled open a drawer with a number instead of a name on the front. When he folded back the sheet, there was my father, older and smaller than the version stuck in my memory.

His face was lined, his beard more white than gray, his hair cropped short like he was still following some regulation from long ago. The scar along his jaw from an old training accident stood out against the pale of his skin. His hands, the same hands that had once held pressure on strangers’ wounds in a war zone and slammed doors in our tiny rental, lay still on his chest. For a second, I felt twelve years old again, watching him sleep in his armchair with the TV still on.

“Is this your father, ma’am?” the technician asked, pen ready over a clipboard.

“Yes,” I said, my voice flat. “That’s him.” I signed where they told me to sign, initials here, full name there, authorization for release. No tears came, just a dull ache behind my eyes and the feeling that I was, somehow, signing the last page of a book I’d never wanted to read.

Outside, the air felt too warm after the cold of the morgue. I wrapped my arms around myself while Reggie leaned against the hood of his truck, watching me with the patience of someone who had seen a lot of people say goodbye in a lot of different ways. Without a word, he reached into his jacket pocket and took out a small ring of keys attached to a brass tag.

“This is his,” he said. “Room at the veterans’ building on Maple, and a locker he rented out near the bus depot. He wanted you to have whatever’s there. Said there was something you needed to see.” He held the keys out, the metal catching the afternoon light.

“Throw it all away,” I answered too quickly. “Donate it, burn it, I don’t care. I don’t want anything from him.” The words came out sharp, but even I could hear the shake under them. Reggie didn’t pull his hand back.

“Maybe that’s what you’ll decide after you look,” he said. “But Doc spent a lot of years putting things in those rooms instead of saying them out loud. Seems a waste to let strangers decide what parts of him stay or go.”

I told myself I was only taking the keys so I could make sure nothing dangerous or embarrassing ended up in a thrift store somewhere with our last name attached. That afternoon, after picking up my son and dropping him with my neighbor again, I drove to Maple Street and parked in front of a low brick building with a faded sign that just said “Veterans Housing.”

The hallway smelled like coffee and cleaning spray, lined with identical doors and bulletin boards full of flyers for support groups and community dinners. My father’s room number was written in Reggie’s careful block letters on the brass tag. My hand shook just a little as I slid the key into the lock and turned it.

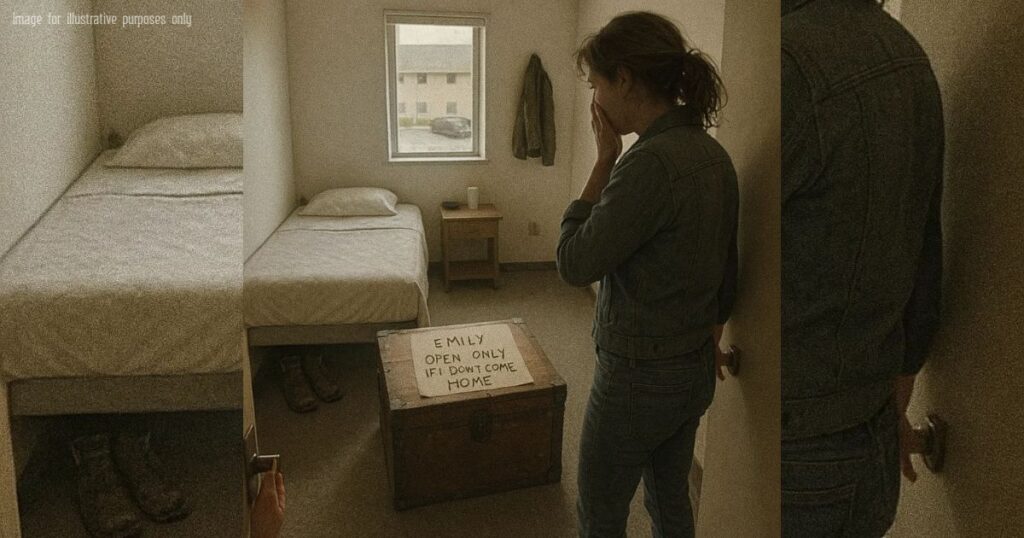

The door opened with a soft click, revealing a small, neat room with a single bed, a worn chair, and a narrow window looking out over the parking lot. Everything was quiet and still, like a hotel long after checkout. In the center of the room, sitting on the floor at the foot of the bed, was a plain wooden trunk with a folded piece of paper taped to the lid.

In my father’s uneven handwriting, all capital letters, were five words that made my breath catch in my throat: EMILY – OPEN ONLY IF I DON’T COME HOME.

Part 2 – The Room the War Built

The door clicked shut behind me, and for a moment all I could hear was the hum of the old air conditioner in the window. The room was smaller than I expected, but it was tidy in a way my childhood home almost never was. Bed made, sheets tucked tight like he’d learned in some long-ago barracks. A pair of boots lined up neatly under the frame, laces coiled on top.

The trunk sat like an accusation in the middle of the floor. The note with my name on it fluttered slightly in the draft from the window, as if it were breathing. I knelt down without meaning to, fingers tracing the uneven letters. “Open only if I don’t come home.”

“Guess you got your wish,” I muttered, even though the words felt cruel the second they left my mouth. The lid was heavier than it looked, and it creaked as I lifted it, releasing a faint smell of old paper, cedar, and something like hospital disinfectant that never really leaves a medic’s hands.

I expected junk. Tools, maybe, or medals, or a tangle of clothes he never got around to folding. Instead, the first thing I saw was a bright splash of yellow against a manila envelope. It was a finger painting, the kind kindergarten teachers hang on walls—my crooked attempt at a sun, a lopsided house, and stick figures holding hands.

In the corner, in a smaller, neater handwriting than the rest of the mess on the page, it said “Emily, age 5.” Underneath, in his block letters, was written: “First art show – she said I could come see it if I was ‘calm.’ I was. She was so proud.”

My throat tightened. Beneath the painting were more papers, carefully stacked and held together with rubber bands that had gone brittle. My kindergarten progress report. “Emily is curious, kind, and helps others without being asked,” the teacher had written in looping script. It was the same form my mom had waved at him one night, shouting that he wouldn’t even read it because he was too busy staring at the TV.

He’d kept it. He’d kept all of them.

There were report cards from first grade, second, third. Photos from school picture days, each one with my forced smile and increasingly frizzy hair. The awkward fifth-grade shot with the braces I’d sworn I would never forgive them for, and the eighth-grade photo where I’d chopped my hair too short. The Polaroid from my high school graduation, my gown crooked, my smile real for once.

Each photo had a note on the back in those same clumsy block letters. “Didn’t get a ticket, but watched from fence.” “Couldn’t go inside, court order said stay away when I was drinking. Stayed in truck until lights went off.” “She looks strong. She looks okay. That’s enough.”

I sank down on the worn carpet, the trunk open like a mouth between my knees. Memories I had packed away as “proof he didn’t care” now sat in my lap, labeled and dated. Under the school stuff was a thick rubber-banded stack of receipts, folded neatly in half and organized by year.

The top one was from a daycare center I barely remembered. “Weekly tuition – Emily Harper.” Another from a summer program at the community center where I’d learned to swim. One from a used bookstore with a note: “She finished all the library books, needed more.” A payment confirmation for my first semester of nursing school, routed through some scholarship fund I’d always believed had picked my name from a pile by chance.

I flipped through them, my stomach dropping with each new line item. Dental payments. Pediatrician visits. Rent checks written to my mother’s old landlord, even after she’d told me he never helped with “anything useful.” A crumpled bank slip showing a withdrawal that matched, to the dollar, the security deposit I’d needed for my first apartment with my fiancé.

All those nights I’d cursed him for choosing the bar over my future, and here were the numbers proving he’d been paying for that future while I wasn’t looking.

I found a spiral notebook near the bottom, the cover worn and soft. Inside, the pages were lined with his jagged handwriting, part ledger, part confession. “Extra shift at warehouse – back pain worse – use for Emily’s books.” “Skipped my meds this month to cover her lab fees. Not smart, but she’s smarter than I’ll ever be.” “Asked the VA about more counseling. Told them I was fine so they’d leave the slot for someone worse off. Hope that wasn’t a lie.”

I wiped at my cheeks before I realized I was crying. The sound that came out of me was small and ugly, not the cinematic sob I’d always imagined for moments like this. I closed the notebook, afraid that if I kept reading I’d find something I couldn’t carry.

At the very bottom of the trunk, under a folded flannel shirt that smelled so strongly of his laundry soap it made my chest ache, there was a plain white envelope. My name was written on the front, and the edge of the paper was worn where his thumb had probably run over it again and again.

My first instinct was to put it back. To close the lid and walk away and pretend I’d never seen any of this. But my fingers were already slipping under the flap, already pulling out the single sheet of paper inside.

“Em,” it began, and I had to pause because that was what he used to call me when things were good, on the rare mornings he made pancakes in the shape of Mickey Mouse and pretended everything was normal.

“I don’t know if you’ll ever read this. I don’t know if I’ll get the courage to hand it to you. So I’m putting it here, with the rest of the things I was too clumsy to say out loud.

You were right the night you told me I brought the war into our house. I did. I brought it into every room I ever slept in after I came home. I thought I could outrun it by working more, by drinking less, by sitting very still. None of that worked the way I hoped.

I was a bad husband. I scared your mother. I scared you. I will always be sorry for that. But being broken doesn’t mean I didn’t love you. It just means I didn’t know how to show it without breaking you too, and I refused to do that.

So I stayed back. I sent money when I could. I watched from a distance when I wasn’t supposed to be there at all. You never needed to thank me for any of that. That was my job. You were the one good thing I ever made.”

The words blurred, and I blinked them back into focus. At the bottom of the page, there was one more line, written darker than the rest, as if he’d pressed the pen into the paper.

“If I’m gone by the time you see this, and you want to know who I really was, not just who I was in your worst memories, go to the center on Thursday. Ask for Marcus. Tell him you’re Doc’s girl.”

I read that last sentence three times, the phrase “Doc’s girl” digging under my skin. That was what they’d called me when I was little and he brought me to cookouts on base, before the nightmares got worse and the invites stopped coming.

I folded the letter carefully and slid it back into the envelope, then set it on top of the stack of receipts and report cards. My legs felt numb as I stood up. The room around me hadn’t changed, but it felt different now, like I’d been dropped into a stranger’s life that just happened to share my father’s name.

On the small nightstand beside his bed was a folded church bulletin with notes scribbled in the margin. “Ask about group for families,” one read. “Can I bring Em? Too late?” Another scrap of paper had a list of times: “Thursday – 6 p.m. Group. 7 p.m. check bus schedule. 8 p.m. call center about volunteering.”

I stuffed a few of the papers into my bag almost without thinking—the letter, the notebook, a couple of receipts with my name on them. Proof, I told myself, though I wasn’t sure proof of what. Proof that he’d tried? Proof that I’d been wrong? Proof that both could be true at the same time?

As I locked the door behind me, the hallway seemed longer than before. Voices drifted from down the corridor—a TV game show, someone laughing, a cough that turned into a wheeze. For the first time, I wondered how many of these doors hid stories like my father’s, men and women who had gone away and come back and never fully arrived.

Outside, the evening light had gone soft, painting the parking lot in gold. Reggie was sitting on the tailgate of his truck, elbows on his knees, eyes on the ground. He stood when he saw me, searching my face for something he didn’t ask about.

“Well?” he said gently. “You find what he left for you?”

I swallowed, feeling the weight of the envelope in my bag like a stone. “I found enough to know I didn’t know him at all,” I said. “And apparently I’m supposed to go talk to someone named Marcus on Thursday.”

Reggie’s mouth twitched, almost a smile. “Marcus,” he repeated. “He runs the group at the center. Your old man practically lived there when he wasn’t working. If anyone can fill in the blanks, it’s him.”

The center. Thursdays. It sounded like the last place I wanted to spend my free time, sitting in a room full of veterans talking about things that had already ruined enough of my life. But the letter’s last line echoed in my head like a drumbeat.

Tell him you’re Doc’s girl.

“I don’t know if I can do this,” I admitted, surprising myself with the honesty. “I’ve spent so long being angry. I don’t even know who I am if I’m not mad at him.”

Reggie leaned back against the truck, his cane resting between his boots. “Then maybe it’s time you find out,” he said. “Thursday, six o’clock. We’ll be there whether you show up or not. But if you want to hear who your dad was when you weren’t in the room, that’s where you start.”

I looked back at the brick building, at the window I guessed was his. A thin curtain fluttered, catching the last of the daylight. For the first time since the nurse had called, I felt something that wasn’t pure resentment or numbness.

It felt a little like fear. And maybe, buried underneath, the smallest hint of hope.

“I’ll think about it,” I said, sliding into my car.

But as I drove away, my eyes kept flicking to the calendar app on my dashboard display. Thursday was three days away, and the words on my father’s letter burned in my mind like a mission I hadn’t agreed to but couldn’t ignore.

Part 3 – The Life He Paid For

I didn’t sleep much the night after I opened the trunk. Every time I closed my eyes, numbers danced behind my eyelids—tuition amounts, rent payments, the price of braces and textbooks and bus passes. They wove together into a story I didn’t recognize, one where my father was the one holding everything up while I told myself he only ever knocked things down.

By morning, the edges of my anger felt less sharp and more like a dull, throbbing bruise. I made breakfast for my son, packed his backpack, and smiled in all the right places, but my mind stayed in that cramped room on Maple Street. When he was finally settled in his classroom and I sat in my car alone, I pulled the letter out of my bag and read it again.

“If you want to know who I really was…go to the center on Thursday. Ask for Marcus.”

I had a twelve-hour shift at the hospital that day, the kind that usually swallowed me whole. But between blood pressure checks and medication rounds and arguing with insurance reps on the phone for my patients, my thoughts kept circling back to that one sentence. Who I really was. As if the man I remembered punching holes in the drywall and apologizing with cheap fast food was just one version of him, not the whole.

On my lunch break, I opened a different app and pulled up my student loan account, the one I’d been dutifully paying every month since graduation. The balance was lower than I expected. I scrolled back through the payment history, frowning, then frowned harder.

There, nestled between my regular payments, were three large lump sums that I definitely hadn’t made. The first hit the account the year I graduated. The second came just before my son was born. The third was dated about eight months ago.

Each one corresponded almost perfectly with the dates on bank slips and money orders I’d seen in my father’s trunk. I felt my stomach turn over as I realized what that meant.

All those years I’d told people I’d “done it on my own,” that I’d put myself through school without help from a man too busy feeling sorry for himself. And all along, he’d been quietly chipping away at the debt I thought belonged solely to me.

The realization sat heavy in my chest all afternoon. When an elderly patient asked if I was alright, I pasted on a smile and blamed it on the long shift. When a coworker invited me for drinks after work, I said I had to get home to my son. It wasn’t a lie, but it wasn’t the whole truth either.

At home that evening, after dinner was cleaned up and my son was in pajamas, he crawled into my lap on the couch with his favorite dinosaur blanket. “Mom,” he said, his voice muffled against my shoulder. “Are you sad?”

Kids have a way of cutting through whatever mask you think you’re wearing. I hesitated, then decided he deserved more than the automatic “No, I’m fine.”

“A little,” I admitted. “I’ve been thinking about Grandpa.”

He pulled back enough to look up at me, eyebrows scrunched. “The grandpa we don’t see?” he asked. That was what I’d started calling my father when my son was old enough to ask questions. One grandparent he knew only through pictures and video calls. One he knew only as an absence.

“Yeah,” I said softly. “That one.”

“Did he do something bad?” my son asked. “Like the kids who don’t share toys at school?”

The easy answer sat on my tongue. Yes, I could have said. He yelled. He slammed doors. He scared us. He didn’t show up when he should have. All true. But now I knew there was more truth than I’d been telling.

“He did some things that hurt people,” I said carefully. “And he had a hard time after he came back from…a place that hurt him, too. He didn’t always know how to be kind. But he tried, in some ways I didn’t see for a long time.” My voice caught on that last part.

My son nodded like that made sense. “Sometimes kids in my class scream when they’re mad,” he said. “But then they say sorry later. Ms. Carter says our feelings are big, but we’re still good kids.” He yawned, the seriousness of his expression evaporating into sleepiness. “Maybe your grandpa had big feelings too.”

He was asleep five minutes later, but his words stayed with me. Maybe your grandpa had big feelings too. It was such a simple way to look at it, no politics, no long diagnosis codes, just a child recognizing that some people’s insides are louder than others.

After I laid him in his bed and turned on the nightlight, I pulled the notebook from my father’s trunk out of my bag. The pages whispered as I flipped through them, past grocery lists and appointment reminders and worn corners. Here and there he had made notes that read less like a ledger and more like a journal.

“Nightmares bad this week. Woke up shouting. Scared the guy down the hall. Apologized. He said he understood. Doesn’t make me feel better.”

“Skipped group tonight. Felt too tired to talk about the same ghosts again. Might skip next week too. That’s how trouble starts, Doc. You know that.”

“Saw Emily’s name on the hospital website today. Picture of her in scrubs. She looks like she knows what she’s doing. Proud. Kept the page open for an hour. Couldn’t get myself to walk through those doors.”

He’d printed out the photo from the hospital website and tucked it between the pages, the ink slightly blurred where someone—him, I realized—had traced the outline of my face.

Near the back, most of a page was taken up by a single paragraph.

“I know she hates me. I earned that. I brought home things I should’ve left over there. But every time I think I should give up trying to help, I remember how small her hand felt in mine the day she was born. A medic knows when to call a time of death. A father doesn’t get to do that with his love.”

I closed the notebook and pressed it against my chest, as if I could somehow press the words back in time and wedge them between us on all the days we’d chosen silence instead.

Thursday loomed closer with every passing hour. Part of me wanted to drop the trunk back off at the housing office, hand them the keys, and tell them to send whatever they wanted to charity. Another part, the part that had spent all day reconciling my student loan account with numbers in my father’s handwriting, knew I couldn’t unknow what I knew now.

The next afternoon, on my break, I called the number for the center listed in the back of the notebook. A woman answered, her voice brisk but kind.

“Community Veterans Center, this is Carla.”

I cleared my throat. “Hi. This is…this is Emily Harper. I was told to ask for someone named Marcus? I’m…Doc’s daughter.” The word felt strange in my mouth after years of avoiding it.

There was a pause, then a soft exhale that sounded almost like relief. “Oh, honey,” Carla said. “We’ve been wondering if you’d call. Hold on, I’ll get him.” Paper rustled, a door opened, muffled voices traded a few words.

Then another voice came on the line. Deep, steady, with a faint drawl I couldn’t place. “Emily? This is Marcus. I served with your dad after he came home.” He chuckled once. “He’d call that ‘serving on the home front,’ but really it was us trying to keep each other upright.”

I didn’t know what to say to that, so I went with the obvious. “He told me to come see you,” I said. “In a letter. I found it in his room.”

“Yeah,” Marcus said quietly. “He told us he’d left some things for you. He was always better at packing boxes than unpacking his heart.” There was a pause. “We meet on Thursdays at six. You’re welcome to sit in, or we can talk after, or both. No pressure either way.”

“What kind of group is it?” I asked, even though I had a feeling I already knew.

“Mostly guys like me and your dad,” he said. “People who went over there and came back with more baggage than we left with. A few spouses, a few grown kids sometimes. We talk about…the stuff nobody wants to hear on TV between commercials.” He hesitated. “Your dad was one of the first to show up when we started. One of the last to leave most nights.”

The idea of my father sitting in a circle of folding chairs under fluorescent lights, talking about feelings, didn’t fit easily with the image I’d carried of him for so long. But then again, nothing I’d seen in the last forty-eight hours fit that image either.

“I’ll be there,” I heard myself say. “Thursday. Six o’clock.”

“Good,” Marcus said simply. “We’ll have coffee on. Your dad always complained it was too weak, but he drank it anyway. Guess we’ll see if you complain too.”

After I hung up, I sat in the staff lounge for a long moment, staring at the vending machine while my heart raced. I wasn’t sure whether I was more scared of what I might hear about my father from these men who’d known him, or of what I might have to admit about myself in front of strangers.

On Thursday evening, I found myself pulling into the gravel parking lot of the center ten minutes early. The building was squat and unremarkable, a former office space converted into something softer by the addition of a mural on one wall—hands passing a folded flag from one generation to another.

Inside, the air smelled like coffee, old carpet, and the faint tang of sweat. Flyers covered a corkboard near the entrance: support groups, job training workshops, notices for free legal clinics, a potluck scheduled for the end of the month. A handwritten sign on the door to one room read: “THURSDAY GROUP – ALL ARE WELCOME. LEAVE RANK AT THE DOOR.”

I hovered in the doorway for a second, taking in the circle of mismatched chairs and the men and women filling them. Some wore old service caps, some wore plain t-shirts, some had prosthetic limbs or canes. They were laughing at something, the kind of weary, gallows humor born of shared experience.

“Emily?” a voice said behind me.

I turned to see a man in his fifties, broad-shouldered despite the wheelchair he sat in. His hair was cropped short, more gray than black, and deep lines etched the corners of his eyes. He wore a sweatshirt with the center’s logo on it, and his gaze was steady but kind.

“I’m Marcus,” he said, extending a hand. His grip was warm. “You’ve got your father’s chin. He hated when we told him that, said it made him feel old.”

I almost laughed, a startled sound that broke some of the tension in my shoulders. “I’m not sure that’s a compliment,” I said.

“Oh, it is,” Marcus replied. “Doc was the stubbornest medic I ever met. When he set his jaw, no one could move him. Not bullets, not bureaucracy, not even his own fear.” He gestured toward the circle. “You can sit wherever you like. You don’t have to talk. You can just listen. That’s what your old man did the first few weeks.”

I took a breath and stepped into the room, feeling a dozen pairs of eyes turn toward me. I told myself I was here to learn more about the man whose name was on my birth certificate and my worst memories.

What I didn’t know yet was that I was also about to learn who he’d become in the years when I’d refused to look.

Part 4 – Thursdays at the Center

The chair I chose was near the door, an unconscious exit strategy. Old habits die hard. If things got too intense, I wanted to be able to slip out without making a scene. Marcus wheeled himself into the spot across from me and gave the circle a little clap to get everyone’s attention.

“Alright, folks,” he said. “Before we get into our usual round of ‘how’s your week been,’ we’ve got somebody new with us tonight.” His eyes flicked to me. “This is Emily. She’s Doc’s girl.”

A ripple went through the group at my father’s nickname. Heads turned, expressions shifted. A woman in her forties with a pixie cut and a service dog at her feet smiled softly. An older man with a cane gave a little nod. For the first time, I understood that my father’s identity here wasn’t “the drunk” or “the angry vet.” He was “Doc,” a role that carried weight.

“I—uh—hi,” I managed. “I’m Emily. I’m just here to…listen.” The last word came out smaller than I’d intended.

“Listening’s a good start,” said the woman with the dog. “I’m Carla, in case you call the front desk and forget my voice.”

The group went around, first names only. A former helicopter pilot. A logistics specialist. A military police officer. A corpsman. A National Guard member who’d been activated during disasters at home, not overseas. A couple of spouses who had never worn a uniform but had lived in the blast radius of what it meant.

As they shared bits of their weeks—good days, bad nights, triggers that had snuck up on them at the grocery store or during a fireworks show—I realized something that made my throat tighten. They spoke about my father in the present tense.

“Doc used to say…”

“Doc always did this thing where…”

“Doc taught me to…”

I raised a hand when there was a natural pause. “You all keep talking about him like he’s still here,” I said before I could second-guess myself.

Marcus’s eyes softened. “Well,” he said slowly, “for a lot of us, he is. The stuff he built here didn’t die when he did.”

I frowned. “He built…what, exactly?”

He gestured toward a bulletin board on the side wall. I hadn’t noticed it before, tucked beside the coffee table and the stack of donated magazines. Up close, I could see it was cluttered with photos and index cards.

Some cards had names and phone numbers—“Need a ride to appointment on Tuesday,” “Looking for help fixing sink,” “Can babysit so spouse can get a break.” Others were thank-you notes scribbled in messy handwriting. “Thank you for the food box.” “Thank you for the rent help.” “Thank you for not making me feel like a failure.”

“The Quiet Fund,” Marcus said, rolling closer. “Started as Doc slipping cash into envelopes and leaving them on my desk with a sticky note. ‘For the kid with no lunch money.’ ‘For the guy whose truck broke down.’ That sort of thing. I told him if he was going to keep doing it, we might as well make it official.”

“So you made a bulletin board?” I asked, because it was easier than admitting that I hadn’t imagined my father organizing anything more complicated than his own pillbox.

“We made a pattern,” he said. “People around here…we’re not always good at asking for help out loud. Pride’s a hell of a thing. So we wrote things down instead. Needs. Offers. Doc kept track. When he couldn’t cover something himself, he’d find someone who could. He’d show up to fix a roof, or drive someone to a job interview, or sit with a guy all night so his wife could sleep.”

I stared at the board, at the web of quiet kindness laid out on cork and pushpins. “I didn’t know,” I said, hating how hollow it sounded. “I didn’t know any of this.”

“Not your fault,” the older man with the cane piped up. “He was stubborn about keeping his worlds separate. Said he’d already done enough damage in yours.” He shifted in his seat, wincing. “Figured if he could make himself useful here, maybe it would balance the scales a little.”

Marcus glanced at the clock and then back at the group. “Alright,” he said, “we’ll steer back on track in a minute. But since Emily’s here, and Doc’s on a lot of our minds, maybe tonight we can share some Doc stories, if that’s alright with you.” He looked at me. “Only if you want to hear them.”

I swallowed. Part of me wanted to run. Another part—smaller but growing—needed to know what kind of man my father had been when he wasn’t standing in our kitchen, hands shaking and eyes far away.

“I…yeah,” I said. “I want to hear.”

The stories came in waves, from different mouths but woven together like pieces of the same fabric.

The helicopter pilot, whose hands still trembled when the room got too quiet, told me about the time a thunderstorm hit while they were doing outdoor maintenance on the roof. He’d frozen at the sound of a sudden crack of thunder. “Next thing I know,” he said, “Doc’s hand is on my shoulder, and he’s narrating the weather like it’s a baseball game. Gave my brain something else to latch onto.”

The woman with the service dog talked about panic attacks that left her gasping on the floor. “He never tried to fix them,” she said. “Just sat there and breathed loud on purpose, so I’d have something steady to sync up with. Said, ‘Medics don’t leave the tent just because the patient’s scared.’”

A younger man, probably not much older than me, shared about his first night at group. “I didn’t talk at all,” he said. “Thought I was too messed up even for this place. On my way out, Doc handed me a coffee and said, ‘You coming back next week, Private?’ I told him I wasn’t a private anymore. He said, ‘Tonight you are. You’re under my care until you say otherwise.’ And damned if I didn’t show up the next week, just to prove him wrong.”

I listened, my father’s silhouette growing clearer with each anecdote, layered on top of the memory of him hunched over our kitchen table with a bottle he wouldn’t put down. It was dizzying, trying to reconcile the two.

“How did he—” I started, then stopped.

Marcus prompted gently, “How did he what?”

“How did he take care of all of you,” I asked, “when he couldn’t take care of himself? Of us?”

The room fell quiet. It wasn’t the uncomfortable silence from earlier; it was thoughtful, like everyone was checking their own memories for an answer.

“Sometimes,” Marcus said slowly, “the only way a man can stand his own ghosts is by standing between other people and theirs. Doc was good at that. Gave him a reason to get out of bed, even on the days his head was a mess.” He paused. “Doesn’t mean he did right by you. Two things can be true. He could love you and still hurt you. He could fail you and still fight like hell to make sure you had chances he didn’t.”

The words landed hard. Two things can be true.

I thought of the chair flying across our living room, splintering against the wall while my mother shouted and I covered my ears. I thought of the rent receipts with his name on them. The way he’d stayed away from my graduation because a restraining order said he had to, then watched from a distance anyway.

“Did he ever—” I forced myself to ask the question that had been lurking under my skin since I found the trunk. “Did he talk about me? Here?”

Carla snorted softly. “Talk about you?” she said. “Honey, we got sick of hearing about you some weeks.”

Laughter rippled around the circle, gentle but real. Marcus rolled his eyes dramatically. “Every time you got a new job, we heard a full briefing. When your picture went up on the hospital website, he printed it out and passed it around like it was classified intel. When you had your son…” His voice softened. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a man that terrified and that proud at the same time.”

My heart thumped against my ribs. “He knew about my son?” I asked, even though the pictures in the trunk had already hinted at the answer.

“Of course he knew,” Marcus said. “Small town. News travels. Plus, he…kept an eye on your street, so to speak.” At my raised eyebrows, he added quickly, “Not in a creepy way. He’d ride the bus past your place on his way to the warehouse or the clinic. Said as long as he could see your porch light on, he could sleep.”

The image of him watching from the bus window, hands pressed to the glass like a kid looking into a candy store, made my throat close. For years I’d thought of him as absent by choice. I hadn’t considered the possibility that sometimes staying away might have been his way of protecting us from himself.

“About that night,” I said, the question that had been burning in my brain since the nurse’s phone call finally forcing its way out. “The night he died. They said he collapsed on a bus. Was he…coming from the bar? The center?”

Marcus and Reggie exchanged a look. It was quick, but I caught it. There was something there, something they hadn’t told me yet.

“He wasn’t coming from anywhere,” Reggie said finally. “He was on his way somewhere.”

He looked straight at me, his gaze steady and sad. “He was on his way to the hospital. To you.”

The room tilted. “What?” I whispered.

“You were on the schedule that night,” Marcus said, his voice gentle, like he was easing a bandage off a wound. “Night shift in the ER. He’d finally worked up the nerve to come in and see you at work. Said if he came as a patient’s family member, you’d have to at least say hello.”

I shook my head, heartbeat roaring in my ears. “No,” I said. “No, that doesn’t make sense. Why would he choose that night, after all these years?”

Reggie cleared his throat. “Because he knew you were…alone,” he said. “Marcus, show her.”

Marcus reached into the bag hanging off the back of his wheelchair and pulled out a folded piece of paper. He smoothed it on his lap and then handed it across to me.

It was a photocopy of a bus schedule, times highlighted in yellow. Next to the 11:45 p.m. departure to the hospital stop, in my father’s shaky handwriting, were three words: “GO SEE EM.”

Underneath, in smaller letters, he’d added, “Bring blanket for the baby.”

I stared at the page, my vision tunneling. “What baby?” I asked, even though I already knew.

“Yours,” Marcus said. “Your son. Your neighbor called the center that afternoon. Said she was worried about you. Said you’d been working too many shifts, that the baby wasn’t sleeping, and your husband was deployed again. She asked if someone could check on you. Doc volunteered before she finished the sentence.”

I remembered that day now. The ache in my back, the endless crying, the exhaustion so deep I’d snapped at the neighbor for knocking to see if I needed anything. I hadn’t known she’d reached out to anyone else.

“He was on that bus with a diaper bag one of the ladies from the support group put together,” Carla said softly. “Had formula samples, extra onesies, little socks. He joked he looked like a lost grandpa in the baby aisle. We were all teasing him about it.”

My hands shook as I held the paper. “He never made it,” I said, and it wasn’t a question.

Marcus nodded. “He got as far as the stop two blocks from here,” he said. “Guy on the bus said he clutched his chest, tried to stand, and went down. They called 911. By the time he hit your ER, there wasn’t much anyone could do.”

For a moment, all I could see was the fluorescent light of my own emergency room that night, the blur of patients and alarms and charts. I’d had a strange feeling in my chest around midnight, a sudden urge to step outside and breathe. I’d ignored it, too busy hanging a new IV bag and checking vitals.

I had been in the building when my father died. I’d been twenty yards and a dozen doors away from him while they tried to restart his heart. And I had told a nurse on the phone I wasn’t coming to say goodbye.

The room around me felt very far away. Voices blurred into a low hum. I stared at the highlighted time on the bus schedule like I could rewind it by sheer will.

“Emily,” Marcus said softly. “You okay?”

“No,” I said honestly. “But I guess…that’s kind of the point of all this, right?”

He gave a small nod. “Grief is just love with nowhere to go,” he said. “You’ve got a lot of backed-up traffic.”

I let out a shaky laugh that turned into something closer to a sob. “What else is there?” I asked, clutching the paper. “What else did he…leave?”

Marcus exchanged another look with Reggie, then reached into his bag again. This time, he pulled out a small USB drive on a plain metal keychain.

“Doc didn’t like writing everything down,” he said. “Hands hurt too much some days. So he started talking instead. To this.” He placed the drive in my palm. “There’s a computer in my office you can use to watch them, if you want. Or you can take it home. Either way, if you really want to know who your father was when he thought you’d never see him again…that’s where you start.”

The drive was lighter than it looked, but it felt like it weighed a hundred pounds.

“Videos?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Marcus said. “Selfies, I guess you’d call them. Old man version. He’d sit in the empty group room after everyone left and record messages to you he never sent. Figured if something happened to him, someone should know the whole story.”

My heart hammered in my chest. I could walk away. Drop the drive in the trash, leave the trunk at his room, go back to the life I’d built on the foundation of “he never cared.” No one here would stop me.

Or I could stay. Plug the drive in. Hit play.

I curled my fingers around the metal until the edges bit into my skin.

“Show me the computer,” I said.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬