Part 5 – The Videos He Never Meant Me to See

Marcus’s office was small and cluttered, more storage closet than executive suite. A filing cabinet leaned against one wall, its drawers labeled in thick marker, and a battered desktop computer hummed on a scarred wooden desk. A coffee mug with “World’s Okayest Sergeant” printed on the side sat half full near the keyboard, ring staining the wood beneath it.

He rolled himself in and tapped the side of the monitor like it was an old TV. “She’s slow, but she works,” he said. “You want privacy, I can wait outside. You want company, I can sit right here and pretend I’m not listening while actually listening. Up to you.”

I hesitated, the USB drive digging into my palm. The idea of watching my father talk to a camera while a roomful of his friends waited in the next room felt like peeling off my skin in public. At the same time, the thought of sitting alone with his face on a screen made my stomach knot.

“Can you…stay?” I asked finally. “Just…don’t talk unless I do. Please.”

“You got it,” he said. He maneuvered his chair to the side, close enough that I could feel his presence but not close enough to crowd me. I slid the USB into the port, and a folder popped up with a list of files.

They were labeled simply: “For Em 1,” “For Em 2,” all the way through “For Em 12.” The dates beside them stretched back almost two years. I clicked the first one before I could talk myself out of it.

My father’s face filled the screen, a little grainy, lit by the fluorescent lights of the group room. He sat in one of the metal chairs, jacket off, sleeves rolled to his elbows. For the first few seconds, he didn’t say anything, just stared at the camera like he wasn’t sure it would stare back.

“Okay,” he muttered finally. “Marcus says talking to a blinking red light is cheaper than extra therapy, so here we are.” He scratched at his beard, looking awkward in a way I didn’t recognize from my childhood. “Hey, Em. It’s your old man. Or maybe you never see this and some poor tech finds it after I croak and wonders why I filmed a low-budget confession.”

I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I was holding. His voice sounded like I remembered and didn’t, rougher around the edges, but with a softness I hadn’t heard since I was small enough to fit on his lap.

“I don’t know what you remember,” he continued. “I know what I remember, and it’s not the kind of highlight reel they show at retirement parties. I remember yelling. I remember glass breaking. I remember your eyes big as dinner plates when I shouted at the TV because some reporter said something that sent me back in my head. I remember your mom putting you behind her like I was the enemy.”

He swallowed, eyes glistening. “I also remember you sitting on the edge of the bathtub while I rinsed shampoo out of your hair, telling me about the planet you learned about in school. I remember you falling asleep with your hand on my sleeve so I couldn’t sneak out for a drink. I remember you bringing me a paper from school that said ‘Emily is a helper’ and thinking maybe I hadn’t wrecked everything.”

The video flickered slightly, and he glanced off screen. “Doc, you going all night?” a voice called faintly.

“Gimme ten, Sarge,” my father replied, then looked back at the camera. “Apparently this room is in high demand. I’ll make it quick.” He leaned closer. “I am sorry, Em. Not the drunk sorry where I slur it and fall asleep. The kind where I’d sit in the parking lot outside your apartment and rehearse it for an hour and still never knock.”

The file ended there, abruptly, like he’d run out of nerve or time. My cursor hovered over “For Em 2,” and then I clicked.

In the second video, he held up a printout of the hospital website. My own face stared back at me from the page, smiling in crisp scrubs under the caption “Meet Our Team.” He beamed like a man showing off a trophy.

“Look at you,” he said. “Boss lady at the hospital. I told the guys my kid can probably do more with a blood pressure cuff than I ever did with a whole aid bag. They told me to shut up and pass the chips. I think they were tired of hearing about your promotions.”

He set the paper down, the camera catching the corner of another image beneath it—my son’s newborn photo from the announcement I’d posted online. “I know you didn’t tell me about him,” he said, careful not to say my son’s name. “Probably figured I’d be a bad influence. Can’t argue with that. But if there’s ever a day when you let him know I exist, you tell him his granddad was a medic. Tell him I spent my life trying to put people back together, even when I was the one who broke them in the first place.”

I watched video after video. Some were short, a minute or two where he just said he hoped I was eating enough or not working too many double shifts. Others were longer, filmed after group sessions when his eyes were red and his hands shook.

In one, he talked about a man in the circle who had tried to take his own life. “We sat with him until morning,” my father said. “Took turns talking nonsense so he wouldn’t be alone with his thoughts. I kept thinking about you, about whether anyone is sitting with you when your thoughts get loud. I hope you’ve got someone. If not, that’s on me.”

In another, he held up a letter from the loan company for my student debt, the balance slashed by one of the payments I’d discovered. “Three jobs and my back’s screaming, but this number’s smaller, so I’ll take it,” he said with a tired smile. “One day maybe you’ll realize that ‘I did it on my own’ was actually ‘I did it on top of a very stubborn old man’s shoulders.’ I won’t take credit. Just don’t throw out the receipts.”

The later videos grew more reflective. He talked less about money and more about the war, in careful, general terms. “We weren’t supposed to get attached,” he said in one, staring past the camera. “But you don’t hold a kid’s hand while you’re putting in an IV and not imagine your own. You don’t watch a buddy bleed and not wonder if he ever told his mom he loved her. I came home with a list of names I’ll never forget and a head full of things I’ll never say outright. Group helps. The center helps. You being out there, doing what you do, helps in ways you don’t even know.”

Finally, shaking, I clicked on “For Em 12.” The date stamp was three days before he died.

He looked older in this one, more tired. Deep lines carved his forehead, and a bruise blossomed along one arm where someone had drawn blood. “Hey, kiddo,” he said, voice hoarse. “Doc here. Got my checkup today. Doc number two says my heart’s not what it used to be. I told him it never was that great to begin with.” He tried to chuckle, then winced.

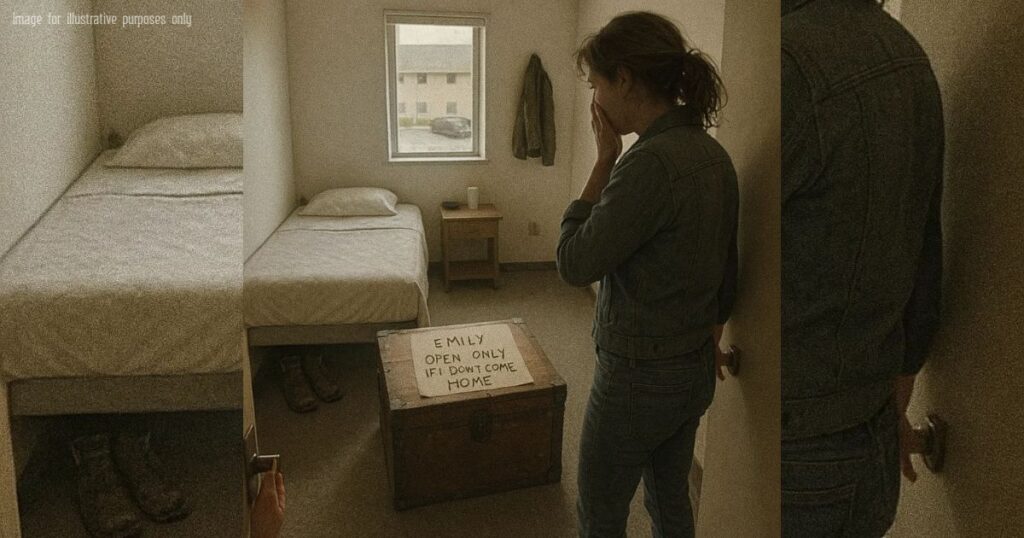

“I’ve been thinking,” he continued. “Took me long enough, right? There’s a lifetime of things I should have told you and didn’t. So I put some of them in that trunk in my room. The rest is up here.” He tapped his temple. “Not all of it’s pretty. You saw enough of the ugly when you were small. I never wanted you to see the war part up close too. That’s why I kept you away when I was at my worst.”

He leaned closer, the camera blurring for a moment before refocusing. “Thursday,” he said. “That’s the day. I’m going to the hospital. Not as a patient. I swear.” His eyes darted away and back. “I’ve got the bus schedule. Carla’s helping me put together a little bag with baby stuff, so I don’t show up empty-handed. If you throw me out, I’ll take it. If you tell security to escort me off the property, I’ll keep my hands where they can see ’em. But I’ve got to at least try. A medic doesn’t call time of death until he’s done every last thing he can. I owe you that much.”

He sat back, rubbing his sternum absently like it hurt. “If something happens, if I chicken out, if this old ticker gives out before I get there, Marcus knows where the backup plan is. Storage unit by the bus depot. Third key on the ring. I put some things there for the boy. Not much, but enough to get him started. Toys, books, a little money. A piece of who I wanted to be as his grandfather, not who I was as your father.”

He looked straight into the camera then, and for a second it felt like he was looking straight at me across time. “I love you, Em,” he said. The words were simple, no drama, no slur. “Always did. Even when I was too messed up to show it. Even when you told me you were done. If you never forgive me, I’ll understand. If you do, it’ll be a miracle I don’t deserve. Either way, you keep that kid safe. You give him the life we both bled for in different ways.”

The screen went black.

I sat frozen, the computer’s fan whirring loudly in the silence. My chest hurt like someone had wrapped a band around it and kept turning, tighter and tighter. Tears blurred the edges of the monitor until all I could see was a smear of light.

Marcus shifted, his chair creaking softly. “He recorded that the last night he came to group,” he said. “Stayed after everyone left. Took him three tries to get through it. Kept cursing at himself for sounding ‘soft.’”

“He was going to come,” I said, voice cracking. “He was really going to show up at my hospital. And I told the nurse I wasn’t coming to say goodbye.”

Marcus’s face was full of something I couldn’t name—sorrow, understanding, maybe a hint of anger on my behalf and my father’s. “You didn’t know,” he said. “Grief will try to convince you you’re omniscient in hindsight. You’re not. You were doing the best you could with the information you had.”

I shook my head, wiping my cheeks with the back of my hand. “He kept everything,” I whispered. “My report cards. My pictures. My debts. And I kept one sentence about him in my head for twenty years. ‘He chose the war over us.’ That’s all I let myself see.”

“Wars don’t give people choices the way you think,” Marcus said quietly. “Sometimes they come home in uniforms. Sometimes they come home in habits. Your dad’s war followed him. Doesn’t excuse the harm. Just explains why he spent the rest of his life trying to pay it down.”

My fingers tightened around the USB drive as I pulled it from the computer. The metal was warm now, like it had soaked up every word.

“What’s in the storage unit?” I asked, my voice steadier than I felt.

Marcus tilted his head. “Some things he bought with money he probably should’ve spent on himself,” he said. “Some things he brought back that he never knew what to do with. Either way, they’re yours now. His last march order was pretty clear.”

I slid the drive into my pocket, feeling it settle there like a second heartbeat. The trunk in his room, the board in the center, the numbers in my loan account, the shaky handwriting on a bus schedule—they were all pieces of a puzzle I’d refused to even look at before.

“I used to think the story was simple,” I said, more to myself than to Marcus. “Dad went to war, came back broken, ruined our lives, and disappeared. Now I don’t know what the story is.”

Marcus gave a small, sad smile. “Maybe that’s the start of the real one,” he said. “The one where you let it be complicated.”

He didn’t push when I stood up. He just held the door open as I walked out past the bulletin board, past the flyer for next week’s potluck, past a framed photo of a younger version of him and my father standing side by side in some dusty place that looked nothing like home.

On my way to the car, I pulled out my phone and scrolled to the photo of my son asleep with his dinosaur blanket. My reflection wavered over his face in the screen, my eyes red and swollen.

“Okay,” I whispered to both of us. “Storage unit next.”

Part 6 – The Storage Unit and the Life He Was Building

The storage facility by the bus depot was the kind of place you only noticed when you needed it. Rows of metal doors stretched in neat lines, each one identical except for a number stenciled near the top. A chain-link fence wrapped around the lot, humming faintly with the sound of traffic on the nearby highway.

The clerk in the small office barely looked up when I handed over my ID and the key with the number scratched into the tag. “Unit 3C,” he said, tapping on a clipboard. “Haven’t seen the guy who rents it in a while. You family?”

The word caught in my throat for a second. “Yeah,” I said finally. “I’m his daughter.”

He nodded like that explained everything and handed me a waiver to sign. “Take your time,” he said. “If you want us to haul anything to donation, we can do that. Just mark what you’re keeping.”

The sun was hot on the back of my neck as I walked down the row toward 3C. My hand shook when I slid the key into the lock, the metal clicking louder than it should have. The door rolled up with a reluctant groan, revealing the dim interior.

For a moment, I just stood there. This, I realized, was the last space my father had curated entirely by choice. His room at the veterans’ building had been assigned; this unit, he had sought out and paid for. It was as close to a secret lair as a broke, aging medic was going to get.

The first thing I saw was a crib.

It stood fully assembled against the back wall, pale wood smoothed by careful hands. A mobile hung above it, little fabric stars and moons spinning lazily in the draft from the open door. A folded blue blanket lay inside, still creased from the packaging, tags attached.

Beside the crib sat a stack of plastic bins, each labeled in thick marker. “0–6 months.” “6–12 months.” “Toddler.” My knees wobbled as I popped the lid on the first one.

Inside were neatly rolled onesies, tiny socks, mittens, hats. A set of board books about animals. A soft stuffed bear with a tag that read “Machine washable.” Each item had a small sticky note attached with my father’s handwriting. “Picked this because strong neck is important.” “Good for teething.” “Book has big pictures—Doc approves.”

I moved to the next bin. Little shoes. A set of building blocks. A baseball glove so small it would barely fit on my hand, much less my son’s. The note on that one said, “In case he wants to throw something that isn’t furniture. Learned my lesson.”

A laugh burst out of me, half hysterical, half genuine. Tears blurred my vision as I opened bin after bin. There was a tiny backpack with dinosaurs, a set of beginner soccer cones, a box of crayons with an art pad. He’d grouped things by age, each stage of childhood he had imagined but never been invited into.

On a shelf above the bins sat a shoebox with “For Em’s boy – later” written on the lid. Inside, tucked among a few small toys and a worn photo of my father in uniform, was a bank envelope. I opened it with trembling fingers.

There were a few hundred dollars in bills, not a fortune by any stretch. Wrapped around them was another ledger page, this one titled “Harper Grandkid Fund.” It listed small deposits over the past couple of years—twenty dollars here, fifteen there, fifty when he got a tax refund. At the bottom, in parentheses, he’d written, “Not much. Maybe first month of community college. Or a used car. Or a bike that actually fits.”

Something in my chest cracked open wider than it had in years. I pressed a hand against my sternum, feeling the thud of my own heart like I was checking a vital sign.

In the corner of the unit was a military footlocker, the kind I’d seen in movies. Its surface was dented and scuffed, a faded last name stenciled across the top. I hesitated before lifting the lid.

Inside, everything was arranged with medic precision. Folded uniforms, neatly coiled belts, a worn aid bag with a red cross patch. Underneath lay a triangular wooden case with a folded flag, not the one from his funeral—he hadn’t had one yet—but one he must have kept from earlier days. Next to it were a few medals, nothing flashy, just ribbons on bars and a silver badge shaped like a caduceus.

There were photos, too. Not the official ones, but snapshots. My father and a handful of other young men in dusty uniforms, faces sunburned and grinning, standing in front of a vehicle with a name painted on the side. A group sitting in a circle, helmets off, someone holding up a deck of cards. In each, my father had a medic bag slung across his body, the strap worn white where it rubbed his shoulder.

Tucked among the photos was a folded piece of paper, brittle with age. It was a letter of commendation, praising Specialist Daniel Harper for “extraordinary courage and selfless service under fire” when he had carried a wounded comrade to safety while administering aid. Someone had underlined “selfless” in pen, hard enough to leave an impression on the paper beneath.

I sat back on my heels, the metal of the footlocker cool against my palms. For so long, “war” had been the monster I blamed for everything. It was easier than blaming a person. Easier than admitting I might have inherited some of the same stubborn streak that made my father both a good medic and a lousy husband.

The unit wasn’t all sentiment. On one wall, he’d mounted pegboard with hooks, each holding a tool. Wrenches, screwdrivers, a level. Beside them hung a laminated chart listing names, broken into two columns. One said “Owe,” the other said “Paid.”

Under “Owe,” there were notes like “Mrs. Lane – porch steps,” “Jorge – truck starter,” “Anonymous – groceries.” Under “Paid,” each name had a date beside it, and sometimes a second note: “Left envelope under mat.” “Gift card, not cash, so they’d use it on food.” “Roof patch held through last storm.”

At the bottom of the chart, in smaller handwriting, was my own name. “Emily – student loans / rent / books / babysitting fund.” The “Owe” side was blank. The “Paid” side had a simple line: “Working on it. Always.”

I didn’t realize I was sobbing until my vision went blurry and my shoulders started to shake. The sound bounced off the metal walls, harsher than I wanted it to be. I clapped a hand over my mouth, as if I could stuff the noise back down.

Someone’s footsteps crunched on the gravel outside, and I hastily swiped at my face. A woman paused at the open door, holding a box labeled “Christmas.” She looked to be in her fifties, with kind eyes and a baseball cap pulled low.

“You alright in there?” she asked. “These places can be…a lot.”

“I’m fine,” I said automatically, then caught myself. “Actually, no. I’m not. But I’m working on it.”

She nodded, setting her box down for a second. “You cleaning out someone’s unit?” she asked. “I did that last year when my brother passed. He was a vet too. Kept every piece of mail they ever sent him, but not a single picture of himself. Go figure.”

“It was my dad’s,” I said. The words felt a little less heavy this time. “He…he was a medic. Here. Overseas. Then here again.”

Her gaze shifted to the crib, the bins, the ledger on the floor. Understanding flickered across her face. “Looks like he was planning for a future he wasn’t sure he’d get to see,” she said. “That’s the cruel thing about hope. Sometimes it outlives us.”

I swallowed hard. “He was on his way to see my son when he died,” I heard myself say. “I was in the same hospital and didn’t know. I spent years telling myself he didn’t care, and now I’m standing in a room full of proof that he did, just…in ways I refused to look at.”

The woman stepped back, giving me space again. “Grief’s a mean teacher,” she said. “Shows up late, gives pop quizzes, never grades on a curve. But it’s still a teacher.” She picked up her box. “Take what helps. Let go of what doesn’t. That’s all any of us can do.”

After she left, I sat on the concrete floor for a long time, surrounded by my father’s version of love. It wasn’t the kind you saw in commercials. It wasn’t tidy or sober or easy. It was bins of baby clothes bought one at a time with money he should have spent on his prescriptions. It was tools hung just so, so he could fix things for people whose names he’d written on a board. It was a ledger of debts he’d tried to repay with a bad back and a stubborn heart.

I gathered up the most important things—the shoebox, the ledger page, a few photos, a small toy truck with its tag still on. I folded the blue blanket from the crib and held it to my face. It smelled like dust and plastic and something underneath, faint but familiar. It smelled like the fabric softener he’d used when I was a kid and he did laundry on his good days.

As I lowered the door, the unit dimmed, the sunlight shrinking to a strip and then vanishing. For a second, panic fluttered in my chest, the sense of another door closing on a man I could no longer talk to.

I pressed my palm against the cold metal and closed my eyes. “I see you, Dad,” I whispered. “I see it now. I’m sorry it took so long.”

When I got back in the car, I didn’t start the engine right away. Instead, I opened the notes app on my phone and typed: “Call hospital administration.” Then: “Talk to ER staff from that night.” And, finally: “Ask neighbor what she told the center.”

If I had spent years building a story on half-truths, then maybe the only way to honor both my pain and his effort was to go find the rest of the truth, no matter how much it hurt.

The night he died, we had passed each other like strangers in a building full of fluorescent light. I couldn’t change that. But I could decide what happened next.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬