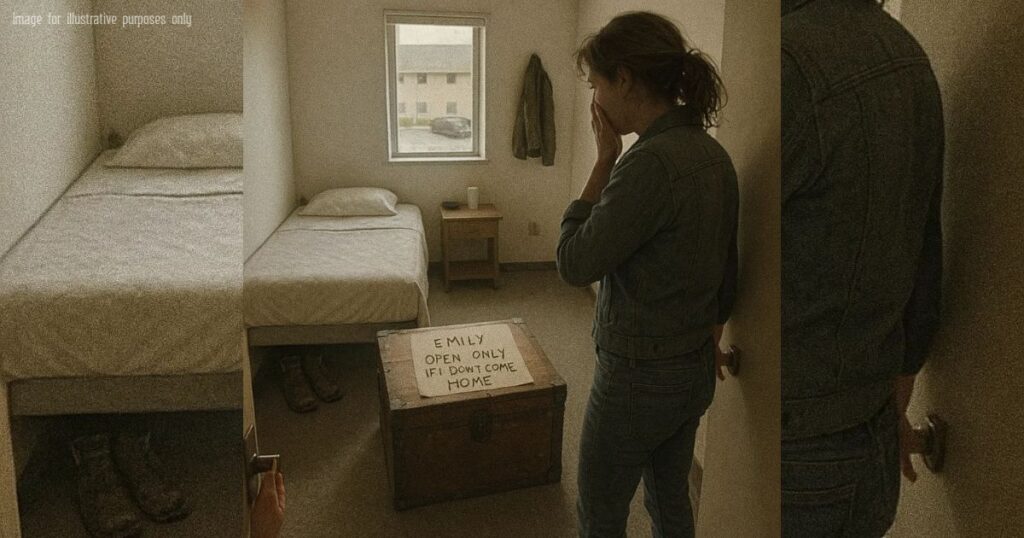

Part 7 – The Night He Didn’t Come Home

Hospitals feel different when you walk in as family instead of staff. The smell is the same—antiseptic, coffee, something fried from the cafeteria that probably shouldn’t be—but the way people look at you shifts. As a nurse, you’re part of the machine. As a daughter, you’re someone begging the machine for mercy.

I checked in at the front desk and flashed my badge, explaining that I needed to review the records from a specific night for a specific patient. There were forms to fill out and policies to navigate, but eventually I found myself in a small conference room with a familiar face across from me.

“Of all the ways I thought we’d finally end up talking about your dad, this wasn’t one of them,” said Denise, the charge nurse who had called me the night he died. She folded her hands around a paper cup of coffee, rings glinting under the fluorescent lights. “I’m sorry for your loss, Emily. And I’m sorry I didn’t push harder on the phone. It felt like I was stepping into something big I didn’t understand.”

“It wasn’t your job to fix twenty years of history in one call,” I said. “That was mine, and I dropped it.” I took a breath. “Can you…tell me what happened? From the hospital side?”

She nodded, glancing down at the chart open on the table between us. “He came in by ambulance just before midnight,” she said. “Found unresponsive on a city bus, CPR started in the field. The paramedics got a pulse back for a bit. He crashed again in the bay. We worked him for a while. He was…persistent.”

The medical part of my brain tracked the words automatically—unresponsive, CPR, pulse, crashed—slotting them into protocols and algorithms. The daughter part of my brain stumbled over every image.

“Persistent how?” I asked, my voice rough.

“When he was conscious, he kept trying to sit up,” she said. “KEPT trying, even with oxygen on and wires everywhere. Every time he could get a breath, he asked the same thing. ‘Is Emily on shift? Is she here? She’s a nurse. She’s good.’” She looked up, her eyes shining. “I thought he was confused at first. Happens a lot. But he said your full name. Harper. Kept saying he wanted to see you. Wanted to hold ‘the little guy’ if they’d let him.”

My throat closed. “I was here,” I whispered. “Downstairs. I felt…strange, like something was off. I just thought it was exhaustion.”

“You had three admissions at once,” she reminded me gently. “You were trying to keep three other families from imploding. We paged you, but you were tied up with a trauma. I made the call not to pull you from that. I thought we had more time with him.”

She slid a folded blanket across the table, blue fabric faded at the edges. “This was his,” she said. “He’d brought it on the bus. We washed it, kept meaning to get it back to whoever claimed him. Then things got busy, and it ended up in the corner of the linen closet until I saw your name on the report last week and realized.”

I picked up the blanket. It was the twin of the one I’d found in the crib at the storage unit. The two halves of a plan he’d never gotten to complete.

“We did everything we could,” Denise said softly. “Sometimes hearts just…stop listening. He went out fighting, if that means anything. The paramedic who rode in with him said your dad was trying to crack jokes between compressions. Said he kept calling him ‘rookie’ and giving instructions.”

“That sounds like him,” I said, managing a watery smile. “Bossing people around even from the gurney.”

After we finished reviewing the chart, I walked down to the ambulance bay. It was quiet, the usual organized chaos taking a brief breath between sirens. I stood by the spot where the paramedics wheeled patients in, the automatic doors sliding open and shut with a soft hiss.

I pictured the scene that night. My father on the stretcher, pale and sweating, one hand clutching a blue blanket, the other reaching for a daughter he hadn’t seen in years. Me in a room down the hall, adjusting IV drips and checking monitors, cursing under my breath at a broken printer.

A medic stepped out to smoke, then paused when he saw me. “Hey, Harper,” he said. “You okay? You’re off tonight, right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Just…visiting a ghost.”

He frowned, then snapped his fingers. “You mean the old vet from a while back? The one who kept asking for you? I rode in on that call.” He leaned against the wall, looking off into the middle distance. “He was something. Kept telling me how to do my job, like he’d invented chest compressions. I finally asked him if he was a medic, and he said, ‘Once a medic, always a medic. Now listen, son, push a little deeper, she’ll kill you if you break my ribs for nothing.’”

Despite everything, a laugh bubbled up. “Sounds like him,” I said again.

“He asked about your kid, too,” the medic added. “Said he’d heard from a neighbor you were running on fumes. Said he used to run on fumes overseas, but it was different when there was a baby involved. More precious cargo, he called it.” He looked at me. “He never said your name with anything but pride, you know. Not once. Even when he could barely catch his breath.”

I took all of that with me when I left, tucking it alongside the USB drive and the ledger in my mental bag. Each piece made the whole picture heavier and somehow clearer.

My last stop was my neighbor’s house. Mrs. Chen opened the door before I finished knocking, as if she’d been expecting me. She was holding a dish towel and smelled like soy sauce and ginger.

“I was wondering when you’d come,” she said, stepping aside. “I made enough stir-fry for two nights. Sit down. Eat something. Grief and empty stomachs don’t mix.”

I followed her to the kitchen table, the same one where she’d fed me dumplings when I first moved in, broke and pregnant and pretending I had everything under control. She set a plate in front of me and sat opposite, folding her towel with precise movements.

“You called the center,” I said. “Before he died. You told them I needed help.”

She nodded. “You were pale and shaking and saying you were fine, which is how I know people are not fine,” she said. “Your son was crying. You hadn’t slept. Your husband was away. I asked if there was anyone I could call. You said no.”

I winced, because I remembered now. The way I’d snapped, “It’s just me. There is no one else,” like a dare.

“So I went through your mail,” she continued calmly. “That paper from the veterans’ building…your father’s address was on it. I looked up the number for the center. I told them you would be mad at me, but a little mad was better than a lot broken.” She met my eyes without flinching. “Your father answered.”

My heart stumbled. “He did?”

“He sounded surprised,” she said. “And scared. Not scared of you, I think. Scared of what you would think. I told him you were working nights and taking care of a baby and trying to be very strong. I said strong people need teams. Soldiers know that, yes? He was silent for a long time, then he said, ‘Where do I sign up?’”

She reached across the table and patted my hand. “I didn’t tell you because I knew you were still hurting,” she said. “And because he asked me to let him be the one to make the choice. It was the first time I’d heard a man sound like he wanted to be useful more than he wanted to be right.”

I squeezed my eyes shut. So many small decisions had woven together into that final night. My neighbor deciding to call. Marcus and Carla rallying to put together a diaper bag and bus schedule. My father choosing to get on the bus instead of back in bed. Me answering the nurse’s call with a heart that had been closed for so long I’d forgotten how to open it.

“I don’t know what to do with all of this,” I admitted. “The guilt, the anger, the…gratitude, I guess. It feels like trying to hold three different storms in one pair of hands.”

Mrs. Chen nodded thoughtfully. “My husband was in a different kind of war,” she said. “We did not talk about it for many years. When he died, I was angry at him for leaving. I was angry at myself for not asking. I was grateful we had the good days we did. I wanted to push it all away and keep it close at the same time.” She smiled sadly. “Eventually, I learned you don’t have to pick one feeling. You just have to pick what you do next.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“I cooked,” she said with a shrug. “I fed the neighbors. I joined a group. I told our story in pieces so it didn’t swallow me whole.” She pointed her chopsticks at me. “You? You go to that center. You go to his funeral. You tell your son the truth, the whole truth, not the simple version. You use what hurt you to help someone else not feel so alone.”

The word “funeral” landed like a stone in the center of the table. We hadn’t had one yet, not really. A morgue, a clipboard, a signature. No flag. No folding. No words over a casket.

“There will be a service,” I said slowly, feeling the idea solidify as I spoke it. “For him. For us. For anyone who needs to say goodbye to their own version of him.”

Mrs. Chen smiled, lines crinkling at the corners of her eyes. “Good,” she said. “Make it loud. The quiet kind of grief is the heaviest.”

On my drive home, the sky was streaked with pink and orange. My son’s bedtime was looming, and the next day’s shift schedule already buzzed in my inbox. Life kept moving, indifferent to my personal revelations.

But somewhere in the middle of all that mundane motion, a thought settled in and refused to move. My father had spent his last years building safety nets for other people, quietly patching holes in their lives while leaving gaps in his own.

Maybe the only way to make any of it bearable was to pick up where he left off. Not as an apology to him, and not as a penance for myself, but as a way to turn all this backed-up love and regret into something that might hold someone else up when they were falling.

The night he didn’t come home, he was trying to get to me. The least I could do now was show up for him when he couldn’t walk into the room on his own.

Part 8 – The Flag and the Empty Chair

The day of my father’s funeral dawned gray and cool, the kind of weather that made you reach for a sweater and a cup of something warm. The cemetery lay on the outskirts of town, rows of simple headstones stretching in neat lines across the gently rolling ground. A small shelter stood near the drive, ready to keep mourners dry if the sky changed its mind.

I had expected something modest. A plain service, a few chairs, maybe a chaplain and a flag. I had not expected a convoy.

The first rumble reached us before we saw them. It wasn’t as loud as the biker engines I’d grown up resenting, but it was steady, a chorus of old trucks and vans and cars pulling into the gravel lot. People climbed out—men and women in worn jackets, some in ill-fitting suits, some in jeans and boots. A few wore their old dress uniforms, seams let out or taken in to accommodate time.

Marcus rolled up in his van, Carla at the wheel. Mrs. Chen arrived with a thermos of tea and a container of cookies, because to her, food was as important as flowers. My coworkers filtered in, faces serious, their scrubs swapped for church clothes. Even Denise came, still in her hospital badge, her expression a mixture of professional detachment and personal regret.

At the front, near the casket draped in an American flag, an honor guard stood ready. They weren’t the high-polish detail you saw at national cemeteries on television, but their uniforms were pressed, boots shined, movements precise. One of them caught my eye and gave the slightest nod, a recognition of sorts.

I sat in the front row with my son beside me, his small hand wrapped around my fingers. He wore a little button-up shirt and the too-big dress shoes I’d bought for weddings and holidays. He looked solemn, eyes darting around to take in the scene.

“Is this like in the movies?” he whispered. “With the trumpet and the folding flag?”

“Something like that,” I said softly. “But this isn’t a movie. This is about your grandpa.”

The chaplain spoke first, offering words about service and sacrifice, about the weight of a uniform and the harder work of taking it off. He didn’t gloss over the struggles veterans faced when they came home, but he didn’t turn it into a political speech either. He kept it human, which was all I could ask.

Then Marcus rolled forward, a piece of paper in his hand. “I’m not great at speeches,” he began, prompting a ripple of knowing chuckles. “Doc used to say if I talked more than ten minutes, somebody needed to check my temperature.”

He glanced at me, then out at the crowd. “Daniel ‘Doc’ Harper was the kind of man who would stitch you up and chew you out in the same breath,” he said. “He’d tell you to quit complaining while he was driving you to your appointment. He was equal parts grumpy and gentle. He’d give you his last dollar and then yell at you if you tried to pay him back.”

He paused, jaw tightening. “He was also a man who made mistakes,” he said. “Big ones. Ones that cost him pieces of his family. He’d be the first to tell you that. He sat in our circle every week and owned his ghosts out loud, so they wouldn’t own him in the dark.” He looked at me again. “He loved his daughter. He loved his grandson. He didn’t always know how to show it, but he never stopped trying to pay off that debt.”

My throat burned. The urge to stand and wave away the praise warred with the need to let the words land.

When Marcus finished, Carla stepped up. “If you are here today because Doc fixed your roof, drove you to a meeting, watched your kids, or slipped you an envelope you never acknowledged,” she said, “raise your hand.”

I turned, and my breath caught. Hands went up across the group—some quick, some hesitant, some halfway as if the gesture itself felt vulnerable. A man in a mechanic’s shirt, a woman in a diner uniform, a teenager in a hoodie. People I recognized from town and people I’d never seen before.

“If you are here because Doc sat with you on a bad night, in this building or another one, and kept you company so you wouldn’t be alone with your thoughts,” she continued, “raise your hand.”

More hands. Some of the same, some new. A couple of them shook.

“If you are here because Doc told you a story about his daughter, about how proud he was of her, about how she did more good in one shift than he felt he’d done in years, raise your hand.”

It felt like the ground dropped out from under me. A sea of hands rose, including Marcus’s, Carla’s, even Mrs. Chen’s. My coworkers’ hands went up too, because they’d heard those stories secondhand in the break room when patients came through and said, “I knew your father.”

My son tugged on my sleeve. “Mom,” he whispered, eyes wide. “That’s a lot of hands.”

“I know,” I whispered back. “I didn’t know there were that many.”

When it was my turn, my legs felt like they were made of wet sand. I walked to the small lectern, the paper I’d written crumpling in my grip. For a moment, I thought I might bolt. Then I saw my father’s name on the small plaque in front of the casket and forced myself to breathe.

“I used to tell a very simple story about my dad,” I began. “He went to war, came back angry, and ruined everything. It was a story that made sense when I was fifteen and scared, and twenty-five and bitter, and thirty and exhausted.” I glanced at my son, then at the rows of faces. “Simple stories feel safe. They don’t leave room for doubt, or regret, or change.”

I unfolded the paper, then decided not to look at it. “In the last few weeks, I have opened boxes and trunks and files I didn’t know existed,” I said. “I have found receipts for braces and textbooks I assumed someone else paid for. I have seen my own report cards covered in my father’s notes, not my mother’s. I have watched videos of a man older and smaller than the one in my teenage memories, talking to a camera because he was too afraid to knock on my door.”

I swallowed hard. “I have also remembered the nights he yelled, and the nights he drank, and the nights I hid under furniture. Both things are true. He hurt us. And he tried, in every clumsy way he knew how, to make sure I had a life where I could help people instead of being hurt by them.”

A breeze stirred the edges of the flag on the casket. I took a breath and kept going.

“My father died on his way to see me,” I said. “He died with a baby blanket in his hands and my name on his lips, in a hospital where I was working two floors away. I will carry the weight of that for the rest of my life. But I will also carry the knowledge that he spent his last years building safety nets for strangers, making sure other people’s kids didn’t go hungry, making sure other families got another chance.”

I looked out at the crowd. “If you are here today and you had a parent who came back from any kind of war—overseas, in their own mind, in the bottle, in the streets—and didn’t know how to come all the way home,” I said, “I want you to know this. You’re allowed to be angry. You’re allowed to be sad. You’re allowed to miss the version of them you never got. And if there’s ever a day when you’re ready to look for the complicated truth, you’re allowed to do that too.”

My voice wavered, but I didn’t stop. “My father was not a hero in the way movies like to sell heroes,” I said. “He didn’t give a speech in front of a waving flag. He gave up days off and medications and pride. He gave up walking into my life so I could walk forward without his shadows on my wall. He failed loudly and loved quietly, and both matter.”

I stepped back, heart pounding. The chaplain nodded, and the honor guard moved into position. The bugler raised his instrument, and the first notes of “Taps” floated across the cemetery, clear and haunting. My son stiffened, then leaned into me, his hand clutching my arm.

The flag was folded with slow, practiced precision. Each movement was deliberate, corners meeting edges until the cloth became a tight triangle of stars and blue. One of the soldiers stepped forward, cradling it in his arms like something fragile.

He knelt in front of me, eyes level with mine. “On behalf of a grateful nation,” he said quietly, “we thank you for your father’s service.”

I took the flag, its weight surprising me. “Thank you,” I managed.

After the service, people milled around, hugs and handshakes and small stories traded like currency. An older woman approached me, her cane tapping the ground. “Your dad used to sit with my husband at the center,” she said. “He never let him skip group two weeks in a row. Said his brain needed more maintenance than his truck.”

A teenager shifted from foot to foot before blurting, “He taught me how to change a tire. And how to breathe when I thought my chest was going to explode. He said panic is just your body forgetting it’s not in a war zone anymore.”

A young mom with a baby on her hip told me my father had shown up with groceries one Thanksgiving when her husband’s paycheck got delayed. A man in a wheelchair said my father had sat with him at two in the morning when the nightmares were too loud.

Each story was a thread, weaving a tapestry I wished I’d seen while he was still alive. Each one hurt and healed at the same time.

As people started to drift away, Marcus rolled up beside me. “This is usually the part where everyone goes home and tries to pretend life is normal again,” he said. “Spoiler alert: it’s not. But it keeps going anyway.”

I looked down at the folded flag in my lap. “He started a lot of things he never got to finish,” I said. “The fund. The storage unit. The group. The idea of being a grandfather.”

Marcus tilted his head. “What are you thinking?” he asked.

“I’m thinking there are a lot of kids out there with parents like him,” I said. “Came back from something they never fully came back from. Kids who grew up learning to read moods like weather reports. Kids who have boxes they’re scared to open.” I met his gaze. “What if we made a place for them? Here. At the center. A group. A fund. Something in his name that isn’t just a stone in the ground.”

His smile was small but real. “Doc always said the only way he could make sense of what he’d seen was by turning it into something useful,” he said. “Turning pain into purpose. Sounds like you’re his daughter, alright.”

I looked over at my son, who was sitting on the grass with Mrs. Chen, carefully examining a dandelion. The wind lifted his hair, and for a moment, in the angle of his jaw, I saw my father’s face.

“Maybe it’s time I learn to be Doc’s girl on purpose,” I said. “Not just by accident of birth.”

Marcus nodded. “We’ll make room,” he said. “We always do.”

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬