Part 9 – Doc’s Girl

The first time I walked into the center on a Tuesday afternoon instead of a Thursday night, the place sounded different. There were still the low hums of conversation and the occasional burst of laughter, but threaded through it were higher-pitched voices, the kind with missing front teeth and questions that didn’t bother with politeness.

We’d put a notice on the board and online: “New group forming: For kids and grown kids of veterans. Art, snacks, no speeches, no rank.” We called it “Doc’s Kids,” partly as a nod to my father, partly because it sounded less scary than “support group for children of trauma.”

In one room, a handful of younger children sat around a table covered in paper and crayons. A girl with braids drew a house with a storm cloud over it, then scribbled the cloud out and replaced it with a sun. A boy with glasses was meticulously coloring a figure in uniform, then adding a dog at its feet because “dogs make everything less scary.”

In another corner, a teenager scrolled on his phone, earbuds dangling. He’d shown up because his mom had dragged him, but he’d stayed because Marcus had told him there was pizza in the next room and no one was going to ask him to share if he didn’t want to.

I hovered near the doorway, unsure where I fit between all the ages. I was a grown woman, a nurse, a mother. I was also very much a kid in some corner of my mind when it came to my father.

“You’re allowed to sit at the grown-ups’ table and the kids’ table here,” Carla said, appearing at my elbow. “We don’t enforce those rules.”

I laughed, tension easing a notch. “I’m still figuring out what my role is,” I admitted. “Facilitator? Participant? Human cautionary tale?”

“Maybe all three,” she said. “That’s kind of the point.”

We’d worked out a loose structure. The kids could draw, play board games, or just exist in a room where the adults knew what it meant when a car backfired and someone hit the floor. The older ones could sit with me and a counselor from the community center, talking if they wanted, not talking if they didn’t.

At the first session, not much was said. A girl mentioned her dad “sleeping a lot and yelling at the TV.” A boy rolled his eyes and said his mom freaked out whenever she heard helicopters. One kid said their grandpa was “weird about fireworks.” They shared in the language of kids, simple and blunt.

When they looked at me, I told them my dad was a medic who came home but didn’t always make it home in his head. “Sometimes he was really fun,” I said. “He made pancakes and told silly stories. Sometimes he was really scary. I learned to tell which version was coming by how he shut the car door.”

They nodded like this was normal. To them, it was.

On the adult side, things were messier. We were used to holding our stories in tidy boxes labeled “Too much” and “Don’t touch.” Sitting in a circle with people who understood what it meant to jump at loud noises or over-apologize when someone raised their voice was both comforting and terrifying.

One woman, about my age, twisted a tissue in her hands. “My dad used to disappear in his own house,” she said. “He’d sit in the recliner and stare at nothing for hours. When I was little, I thought he was mad at me. When I got older, I realized he was back somewhere else. I still get mad at him for leaving, even though he’s been gone ten years.”

A man with a carefully trimmed beard and a wedding ring said his mom had joined the army when he was a toddler. “She came back and couldn’t stand to be touched,” he said. “I thought she hated me. Now I get that she was trying to keep us safe from whatever she was carrying. Doesn’t mean it didn’t hurt.”

When it was my turn, I told them what I’d told no one but Marcus and Mrs. Chen. “I told my father he was dead to me when I was a teenager,” I said. “I meant it. I built a whole personality around not needing him. Now I’m spending my thirties opening boxes that prove he was trying the whole time, just from the wrong direction.”

No one told me to forgive and forget. No one told me to cling to my anger, either. They just nodded, each of them clearly mapping my words onto their own family outlines.

After group, when most people had gone home, I walked down the hallway to the small room we’d claimed for “Doc’s Kids” art. The walls were already speckled with drawings. Some were cheerful, stick figures holding hands in front of houses and dogs and trees. Others were more complicated—blurry scribbles around beds, big words like “LOUD” and “GO AWAY,” careful pictures of flags and boots.

On one sheet, someone had drawn a heart with cracks running through it. In the cracks, they’d written words: “Mad,” “Sad,” “Scared,” “Love.” The pieces fit together to make the whole.

I felt something loosen in my chest.

“Got you thinking?” Marcus asked from the doorway.

“Always,” I said. “I keep waiting for this to feel like a performance, like I’m playing at being a good daughter in public to make up for being a bad one in private.” I shook my head. “But it doesn’t. It feels…honest, if that makes sense.”

He rolled in, looking around at the drawings. “Your dad wouldn’t know what to do with all these feelings on paper,” he said. “He’d probably tell us to hand out duct tape and call it a day. Then he’d sneak back at night and look at every single picture.”

I smiled, imagining him doing exactly that. “There’s still one more thing I haven’t done,” I said. “One more box I need to open. Not literally. Emotionally.”

Marcus raised an eyebrow. “You talking about that letter you’ve been writing in your head for a week?” he asked.

I blinked. “How did you—”

He tapped his temple. “Been around enough grief to know the signs,” he said. “You keep looking at his picture like you’re rehearsing a speech. Write it. Or say it. Or both.”

That night, after my son was asleep and the house was quiet except for the hum of the fridge and the distant siren of a passing police car, I sat at the kitchen table with a blank page.

“Dad,” I wrote, then stopped. It felt strange calling him that on paper. I tried again. “Dear Doc,” I wrote, then scratched it out. Finally, I settled on, “Hey, it’s Em.”

The words came slowly at first, then faster, bypassing the part of my brain that wanted to edit and justify. I wrote about the chair he’d thrown and the pancakes he’d made. I wrote about the nights I’d listened for his footsteps and the years I’d refused his calls. I wrote about the trunk, the storage unit, the USB drive, the bus schedule, the blanket.

I didn’t excuse him. I didn’t excuse myself either. I simply put down the truth as I knew it now, layered and messy.

When I finished, my hand cramped and my eyes burned. I folded the letter and sat with it for a long time, the paper softening under my fingers.

The next day, I took it to his room at the veterans’ housing. The building still smelled like coffee and cleaning spray, the hallways filled with the murmur of TVs and the squeak of wheelchairs. His door opened with the same soft click.

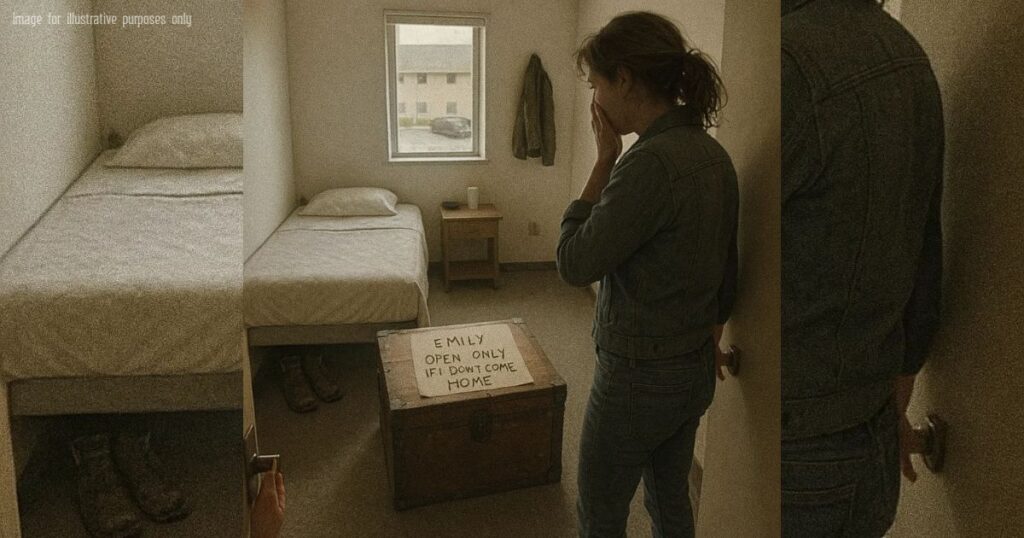

The room was almost exactly as I’d left it, though someone had straightened the bed and dusted. The trunk still sat at the foot, lid closed.

I knelt and opened it, the familiar scent of old paper and cedar washing over me. The stack of report cards, photos, receipts, and his letter to me were all where I’d left them. I slipped my own letter on top, the edges overlapping.

“There,” I said, voice catching. “Now you have a whole conversation, not just a monologue.”

I sat on the edge of his bed, the mattress dipping slightly under my weight. For a moment, I let myself imagine him walking in, rolling his shoulders like he always did when he came in from the cold. I pictured him seeing me there, letter in the trunk, my son’s photo propped on the nightstand.

“I’m still mad,” I said aloud. “I’m still sad. I’m still proud. I still don’t know how to hold all of that without dropping something.” I glanced at the trunk. “But I’m going to keep trying. For me. For the boy. For all the other kids whose parents came home in pieces.”

I didn’t expect an answer. I didn’t get one. But as I stood to leave, the weight in my chest shifted, just a fraction. It didn’t go away. It just moved to a place where it felt more like a part of me and less like a rock pinned on top.

On my way out, I passed a new flyer on the bulletin board near the entrance. “Family Night – Doc Harper Memorial Dinner,” it read. “All welcome. Bring a story, a recipe, or just yourself.”

“Guess you’re a tradition now,” I murmured.

The idea of tradition used to make me itch. It sounded like repetition without choice. Now, it felt more like a chance to turn something painful into something that might, in time, be lightly held.

Being “Doc’s girl” had once meant being collateral damage. Then it had meant being a ghost in his stories to other people. Now, maybe, it could mean being the bridge between his world and mine, helping other people walk a little more safely over terrain that had broken both of us.

I drove home with the window cracked, the air cool on my face. At a red light, my son piped up from the back seat. “Mom? Did Grandpa like dinosaurs?”

I smiled at the mirror, watching his reflection. “He liked whatever you like,” I said. “He just didn’t get to say it out loud. But he bought you a dinosaur backpack before you were even born. It’s in a special box. I’ll show it to you when we get home.”

He grinned, satisfied. “Grandpa was weird,” he declared. “But in a good way.”

“Yeah,” I said softly. “Me too, kiddo. Me too.”

Part 10 – The Kind of Love That Stays

A year after my father’s funeral, the center looked both exactly the same and completely different. The walls were still the same beige, the coffee still tasted vaguely like burnt toast, and the bulletin board by the door was still full of flyers held up by mismatched pushpins. But the energy had shifted.

There was a new board on the side wall now, next to the “Quiet Fund” chart. At the top, in hand-painted letters someone’s niece had crafted, it said “Doc Harper Fund.” Underneath were photos of kids at camp, teens in graduation gowns, adults holding up certificates from training programs.

Each photo had a caption. “Scholarship for EMT certification.” “First semester at community college.” “New laptop for online classes.” Some had notes beside them: “Dad in group for PTSD.” “Mom in recovery.” “Grandpa at every game now.”

The fund wasn’t huge. We weren’t handing out full rides to fancy schools. But we were doing something my father would have appreciated—helping people get from point A to point B without their past blowing up the bridge.

Once a month, we held a “Family Night.” Veterans, spouses, kids, neighbors, and the occasional curious stranger crammed into the main room with crockpots and casserole dishes. Mrs. Chen’s dumplings always disappeared first. Someone’s grandmother made macaroni and cheese that could stop traffic. There were stories told between bites—some funny, some sad, all threaded with the kind of honesty you only hear when people have finally stopped trying to impress each other.

On one of those nights, I stood near the coffee urn, watching my son play cards with Marcus and a couple of other regulars. He’d taken to calling Marcus “Uncle,” though there was no blood relation. “Family by choice” had become a phrase we used a lot around the center.

Carla sidled up beside me with a plate balanced on her hand. “You ever think you’d be spending your evenings like this?” she asked. “Feeding half the town and managing a fund named after your dad?”

“Not in the original life plan, no,” I said. “The original life plan was ‘Get out, stay out, do everything different.’ And then life laughed.”

She chuckled. “Life does that.” She nudged me with her shoulder. “You ready?”

My stomach fluttered. We’d decided to do a short talk that night, a kind of “why we’re here” for the newer faces. Marcus hated public speaking. Carla said she rambled when she was tired. Somehow, I ended up with the job.

I walked to the front of the room and cleared my throat, the chatter slowly dimming. Kids still rustled papers and whispered, but that was fine. I wanted them to know this wasn’t a church service with shushing and stiff backs. This was a living, breathing room.

“Hi,” I said, my voice carrying just enough. “For those of you I haven’t met yet, I’m Emily. I’m a nurse, a mom, and the daughter of a man whose name is on that board over there.”

I gestured toward the “Doc Harper Fund” sign. “My father was a medic in a war that left marks you couldn’t see on an X-ray,” I said. “He came home with nightmares and habits that broke our family in half. For a long time, the only story I told about him was that one.”

I could see some heads nodding, people recognizing the shape of their own stories.

“A while ago, after he died, I started finding things he left behind,” I continued. “Boxes and ledgers and letters and videos. Receipts for braces and textbooks, t-shirts and sneakers, rent payments and groceries I thought someone else had covered. A storage unit full of toys and clothes for a grandson he’d never met. A wall in this very building covered in pictures of my life that he’d printed out and hung up like a private museum.”

I smiled, the memory less raw now. “I learned that while I was building a story about how he’d chosen war and addiction over us, he was building a quiet story of trying to pay for a future he thought he had no right to be part of. Neither story cancels the other out. They just sit side by side, like two people who don’t like each other but have to share a table anyway.”

There was a ripple of low laughter, the kind that recognizes hard truth.

“In my work at the hospital, I see a lot of beginnings and endings,” I said. “Births, deaths, moments where everything changes in a breath. What I’ve learned, both there and here, is that love doesn’t always look like we want it to. Sometimes it looks like showing up. Sometimes it looks like staying away. Sometimes it looks like a roof patched in the rain or a college class paid for twenty dollars at a time.”

I glanced toward the door, half expecting my father to saunter in late with a lame joke about traffic. Old habits die hard, even when the people tied to them are gone.

“My father died on the way to see me,” I said. “He died with my name in his mouth and a baby blanket in his hands, in a building where I was working two floors away. I will always wish I’d known, so I could have held his hand and said something instead of letting a stranger do it for me. But I can’t go back. None of us can.”

I let that hang for a moment.

“What we can do,” I said, “is decide what kind of story we tell from here on out. We can take the pain that was handed to us and pass it on, unchanged, to the next generation. Or we can stop, right here, and say, ‘This is where the pattern breaks.’ We can turn our fathers’ and mothers’ and partners’ war stories into fuel for something better.”

Behind me, on the wall, was a framed photo. It showed my father in his younger days, arms crossed, medic bag on his hip, a crooked smile on his face. Next to it was a more recent picture of my son holding a stethoscope to Marcus’s chest, tongue sticking out in concentration.

“Being the child of a veteran, or any parent who fought their own battles, is complicated,” I said. “We carry their stories in our bones whether we want to or not. We learn to listen for footsteps and slammed doors, for the clink of bottles or the click of locked bathroom doors. We get good at reading faces and terrible at asking for help.”

I spread my hands. “Here, we’re trying something new. We’re trying to teach ourselves and our kids that it’s okay to say, ‘That hurt me,’ and still say, ‘I know you were hurting too.’ We’re trying to build nets like my father did, on purpose and out in the open, instead of in secret storage units by bus depots. We’re honoring the parts of our parents that tried, while being honest about the parts that failed.”

I saw Mrs. Chen in the back, her hands folded over her stomach, eyes shining. I saw Denise from the hospital, standing near the door, her expression a mixture of professional curiosity and personal investment. I saw a teenage boy with crossed arms and a guarded face, his eyes surprisingly wet.

“My father wasn’t perfect,” I said. “He drank when he should have talked. He shouted when he should have listened. He walked away when he should have stayed. But he also worked three jobs so I could go to school. He sat in circles in this building and told the truth about his ghosts so they wouldn’t jump out at other people in the dark. He checked on my porch light before dawn for years, just to make sure I was still here.”

I took a breath, feeling the familiar ache settle in a place that had, over time, become more bearable. “He loved me with a rough, clumsy, relentless love that stayed even when his body didn’t,” I said. “He loved me in receipts and reports and recorded messages. He loved me in ways I didn’t see until it was too late to say it back.”

I looked at my son, who had paused his card game to listen. His eyes were wide, his hand resting absentmindedly on Marcus’s wheelchair.

“I spent thirty years hating my veteran father for the ways war broke him,” I said, letting the words settle over the room. “I’ll spend the rest of my life loving him for the ways he still tried to build me a safer world.”

Silence followed, the kind that isn’t empty but full. Then, slowly, people started to clap. It was hesitant at first, then stronger, not the thunder of applause at a concert, but the steady, grounding sound of many hands agreeing that something true had been spoken.

Afterward, people came up in ones and twos. A woman hugged me and whispered that she was finally ready to open the box in her closet. A man said he was going to call his mother that night, not to fix everything, just to hear her voice. A teenager muttered, “My dad’s in that same kind of group. Maybe I’ll stop pretending I don’t care.”

Later, when the room had emptied and the leftover food was packed away, I sat alone for a moment under the hum of the fluorescent lights. The folded flag from my father’s casket hung in a shadow box on the wall, a small card beneath it reading, “In memory of Daniel ‘Doc’ Harper, who served in two wars: one overseas, one at home.”

I thought about all the people like him—men and women whose battles didn’t end when they turned in their uniforms. I thought about their kids, sitting in rooms like mine had been, wondering which version of their parent would walk through the door. I thought about storage units and trunks and letters written and never sent.

Love is not always gentle. It is not always clean. It is not always on time. But sometimes, even when it arrives late and battered, it is still love. It is still worth noticing. It is still worth honoring.

I stood, turned off the lights, and walked out into the cool night air. The stars were faint above the town’s glow, but they were there. My son slipped his hand into mine, his dinosaur backpack bouncing against his back.

“Mom?” he asked as we crossed the parking lot. “Do you think Grandpa can see us?”

I squeezed his fingers. “I don’t know for sure,” I said. “But I like to think that wherever he is, he knows we finally see him.”

He nodded, satisfied with that answer. “Can we say hi anyway?” he asked. “Just in case?”

We stopped by the small patch of grass near the flagpole, the wind tugging at the cloth overhead. My son tilted his head back and waved at the sky.

“Hi, Grandpa!” he shouted. “We’re okay!”

My throat tightened. I smiled up into the dark. “Hey, Dad,” I added softly. “We’re doing the work. You started it. We’ll keep going.”

In the quiet that followed, I felt it again—that strange, steady thing that had begun to grow in the cracks where anger and grief used to live. It wasn’t forgiveness in the greeting-card sense, all tidy and complete. It wasn’t forgetting either.

It was something else. Something like understanding. Something like peace.

The kind of love that stays, even when the war doesn’t end the way you wanted. The kind that remembers the whole story, not just the parts that hurt. The kind that sees the brokenness and the bravery and decides to honor both.

The kind of love my father had for me, imperfect and fierce and hidden in a hundred small acts, finally met by the kind of love I was learning to have for him in return.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta